Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

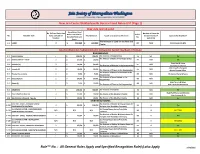

Fixed Nakro LIST (Page 1)

Jain Society of Metropolitan Washington A non-profit tax-exempt religious organization, id # 54-1139623 New Jain Center/Shikharbandhi Derasar Fixed Nakro LIST (Page 1) NEW JAIN CENTER LAND Amount per Fixed No. Of Fixed Nakro Line Number of Passes for Nakro Line Item for Rule** No Donation Item Items available for Total Donation Laabh to be given to the Donors the Ceremonies (if Sponsorship Available? Donation from each No. Donation applicable) Donor The Nirmaan of Land for the New Jain L-1 LAND 2$ 250,000 $ 500,000 R7 N/A Shah Kamlesh & Gita Center SHANKHESHWAR PARSHWANATH BHAGWAN (SHWETAMBAR) DERASAR RANGMANDAP S-1 RANGMANDAP 3 $ 100,001 $ 300,003 The Nirmaan of Rangmandap R5 N/A Yes The Nirmaan of Dome in the Rangmandap S-2 RANGMANDAP - DOME 2$ 25,001 $ 50,002 R5 N/A Yes Shah Atul & Aruna S-3 Bhandar (2) 2$ 10,001 $ 20,002 R5 N/A The Nirmaan of Bhandar in the Rangmandap Shah Dipak and Jyoti Shah Arvind & Sanyukta S-4 Trigado (2) 2$ 10,001 $ 20,002 R5 N/A The Nirmaan of Trigado in the Rangmandap Ajmera Devang & Rani The Nirmaan of Musical Instruments in the S-5 Musical Instruments 1$ 5,001 $ 5,001 R5 N/A Dharamsi Manoj & Kanta Rangmandap The Nirmaan of Sound System in the S-6 Sound System 1$ 20,001 $ 20,001 R5 N/A Yes Rangmandap Shah Paresh & Shilpa S-7 Ghant (2) 2$ 5,001 $ 10,002 R5 N/A The Nirmaan of Ghant in the Rangmandap Shah Harshid & Hemangini S-8 GHABHARA 3 $ 100,001 $ 300,003 The Nirmaan of Ghabhara R5 N/A Yes Dalal Fakirchand and Manjula S-9 Main Ghabhara Door (s) 2$ 15,001 $ 30,002 The Nirman of the Ghabhara Door(s) R5 N/A -

Julia A. B. Hegewald

Table of Contents 3 JULIA A. B. HEGEWALD JAINA PAINTING AND MANUSCRIPT CULTURE: IN MEMORY OF PAOLO PIANAROSA BERLIN EBVERLAG Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 3 13.04.2015 13:45:43 2 Table of Contents STUDIES IN ASIAN ART AND CULTURE | SAAC VOLUME 3 SERIES EDITOR JULIA A. B. HEGEWALD Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 2 13.04.2015 13:45:42 4 Table of Contents Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographical data is available on the internet at [http://dnb.ddb.de]. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. Coverdesign: Ulf Hegewald. Wall painting from the Jaina Maṭha in Shravanabelgola, Karnataka (Photo: Julia A. B. Hegewald). Overall layout: Rainer Kuhl Copyright ©: EB-Verlag Dr. Brandt Berlin 2015 ISBN: 978-3-86893-174-7 Internet: www.ebverlag.de E-Mail: [email protected] Printed and Hubert & Co., Göttingen bound by: Printed in Germany Gesamttext_SAAC_03_Hegewald_Druckerei.indd 4 13.04.2015 13:45:43 Table of Contents 7 Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1 Introduction: Jaina Manuscript Culture and the Pianarosa Library in Bonn Julia A. B. Hegewald ............................................................................ 13 Chapter 2 Studying Jainism: Life and Library of Paolo Pianarosa, Turin Tiziana Ripepi ....................................................................................... 33 Chapter 3 The Multiple Meanings of Manuscripts in Jaina Art and Sacred Space Julia A. -

Ratnakarandaka-F-With Cover

Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni VIJAY K. JAIN Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct vkpk;Z leUrHkæ fojfpr jRudj.MdJkodkpkj Divine Blessings: Ācārya 108 Vidyānanda Muni Vijay K. Jain fodYi Front cover: Depiction of the Holy Feet of the twenty-fourth Tīrthaôkara, Lord Mahāvīra, at the sacred hills of Shri Sammed Shikharji, the holiest of Jaina pilgrimages, situated in Jharkhand, India. Pic by Vijay K. Jain (2016) Ācārya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraõçaka-śrāvakācāra – The Jewel-casket of Householder’s Conduct Vijay K. Jain Non-Copyright This work may be reproduced, translated and published in any language without any special permission provided that it is true to the original and that a mention is made of the source. ISBN 81-903639-9-9 Rs. 500/- Published, in the year 2016, by: Vikalp Printers Anekant Palace, 29 Rajpur Road Dehradun-248001 (Uttarakhand) India www.vikalpprinters.com E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: (0135) 2658971 Printed at: Vikalp Printers, Dehradun (iv) eaxy vk'khokZn & ijeiwT; fl¼kUrpØorhZ 'osrfiPNkpk;Z Jh fo|kuUn th eqfujkt milxsZ nq£Hk{ks tjfl #tk;ka p fu%izfrdkjs A /ekZ; ruqfoekspuekgq% lYys[kukek;kZ% AA 122 AA & vkpk;Z leUrHkæ] jRudj.MdJkodkpkj vFkZ & tc dksbZ fu"izfrdkj milxZ] -

Mable Ringling Museum of Art

INDIAN SCULPTURE IN THE MABLE RINGLING MUSEUM OF ART by R oy C. Cra ven, Jr. INDIAN SCULPTURE IN THE J OHN AND MABL E RINGLING MUSEUM OF ART by R oy C. Craven , J r. Un iversity o f Flo rida Mo n o graph s HUMANITIES i NO . 6, W n ter 1961 DA UNIVERS ITY OF FLORIDA PRESS GAIN SVILLE , FLORI E ’ EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Huma nities Monog raphs T . W TE HE B E T Chairman AL R R R , Profes sor of English CLIN T ON ADAM S Professor of Art H M C ARLES W . ORRIS Professor of Philosophy C A. R BE T . O R SON Profe ssor of Engli sh Associate Professor of German PY GH T 1961 BY THE B D OF CO RI , , OAR COM M ISSIONERS OF ST ATE INSTI T U TI ONS OF FLORIDA L IBRARY OF CONGRESS D 61-63517 CATALOGU E CAR NO . PRINTED BY THE BU LKLEY -NEWM AN PRINTING COM PANY PREFACE In 1956 a group of Indian sculptures was placed on display in the loggia of the John e e sev and M able Ringling Mus eum of Art . Th s o n n enteen works were purchas ed by Mr. J h Ri g ling in the thirties at the clos e of his collecting ’ areer and t en la en in the e c , h y hidd mus um s r r ecor basem ent for some thi ty yea s . R ds which could tell of how and where these sculptures ere o ta ne a e een o t but the fa t t at w b i d h v b l s , c h they constitute a rich gift to the people of Flori a da is apparent in the works thems elves . -

An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide

AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 1 2Prakrit Bharati academy,An Ahimsa Crisis: Jai YouP Decideur Prakrit Bharati Pushpa - 356 AN AHIMSA CRISIS: YOU DECIDE Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 3 Publisher: * D.R. Mehta Founder & Chief Patron Prakrit Bharati Academy, 13-A, Main Malviya Nagar, Jaipur - 302017 Phone: 0141 - 2524827, 2520230 E-mail : [email protected] * First Edition 2016 * ISBN No. 978-93-81571-62-0 * © Author * Price : 700/- 10 $ * Computerisation: Prakrit Bharati Academy, Jaipur * Printed at: Sankhla Printers Vinayak Shikhar Shivbadi Road, Bikaner 334003 An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide 4by Sulekh C. Jain An Ahimsa Crisis: You Decide Contents Dedication 11 Publishers Note 12 Preface 14 Acknowledgement 18 About the Author 19 Apologies 22 I am honored 23 Foreword by Glenn D. Paige 24 Foreword by Gary Francione 26 Foreword by Philip Clayton 37 Meanings of Some Hindi & Prakrit Words Used Here 42 Why this book? 45 An overview of ahimsa 54 Jainism: a living tradition 55 The connection between ahimsa and Jainism 58 What differentiates a Jain from a non-Jain? 60 Four stages of karmas 62 History of ahimsa 69 The basis of ahimsa in Jainism 73 The two types of ahimsa 76 The three ways to commit himsa 77 The classifications of himsa 80 The intensity, degrees, and level of inflow of karmas due 82 to himsa The broad landscape of himsa 86 The minimum Jain code of conduct 90 Traits of an ahimsak 90 The net benefits of observing ahimsa 91 Who am I? 91 Jain scriptures on ahimsa 91 Jain prayers and thoughts 93 -

The Rattas Patronage to Jainism

Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 Vol - V Issue-I JANUARY 2018 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 4.574 The Rattas Patronage to Jainism Dr.S.G. Chalawadi Asst. Professor, Dept of A I History and Epigraphy Karnatak University, Dharwad The Rattas were the significant ruling dynasty, who claimed descent from the Rastrakutas. The earliest record is dated 980 A.D. It comes from the place called sogal. It is believed that sogal was their early capital, from where they shifted first to Soundatti and later on to Belgaum. Their reign continued till 1238 A.D.1 When they were thrown out of power by the seunas of Devagiri. The Rattas served under the Chalukyas of Kalyan and tried to become independent. When the Kalachuries displaced 'the Chalukyas generally the Rattas claimed authority over a large administrative division known as Kohundi or kondi 3000. This included major parts of Soundatti, Gokak, Hukkeri, Raibag, Chikkodi, Bailhongal and Mudhol, Jamakhandi talukas which fall in Belgaum and Bijapur districts. The line of descent of Rattas rulers, commences with Nanna and ends with Lakshmideva - II. In between there were eleven rulers, namely Karthavirya-I, Nanna - I, Erga, Anka, Nanna-II, Karthavirya II, Sena-II, Karthavirya-III, Lakshmideva-I, Karthavirya-IV and Mallikarjuna- II. The Rattas in the course of their rule patronaged both saivism and Jainism. By erecting temples and Basadis and giving much grants to them. One of the earliest references to Jaina patronage under the Rattas is noticed in Soundatti inscription. We are told that Karthavirya-I gave land (grants) to the Basadis constructed by Pritvirama his successors Kannakaira also gave grants to Jinalya at Soundatti. -

Transmitting Jainism Through US Pāṭhaśāla

Transmitting Jainism through U.S. Pāṭhaśāla Temple Education, Part 2: Navigating Non-Jain Contexts, Cultivating Jain-Specific Practices and Social Connections, Analyzing Truth Claims, and Future Directions Brianne Donaldson Abstract In this second of two articles, I offer a summary description of results from a 2017 nationwide survey of Jain students and teachers involved in pāṭha-śāla (hereafter “pathshala”) temple education in the United States. In these two essays, I provide a descriptive overview of the considerable data derived from this 178-question survey, noting trends and themes that emerge therein, in order to provide a broad orientation before narrowing my scope in subsequent analyses. In Part 2, I explore the remaining survey responses related to the following research questions: (1) How does pathshala help students/teachers navigate their social roles and identities?; (2) How does pathshala help students/teachers deal with tensions between Jainism and modernity?; (3) What is the content of pathshala?, and (4) How influential is pathshala for U.S. Jains? Key words: Jainism, pathshala, Jain education, pedagogy, Jain diaspora, minority, Jains in the United States, intermarriage, pluralism, future of Jainism, second- and third-generation Jains, Young Jains of America, Jain orthodoxy and neo-orthodoxy, Jainism and science, Jain social engagement Transnational Asia: an online interdisciplinary journal Volume 2, Issue 1 https://transnationalasia.rice.edu https://doi.org/10.25613/3etc-mnox 2 Introduction In this paper, the second of two related articles, I offer a summary description of results from a 2017 nationwide survey of Jain students and teachers involved in pāṭha-śāla (hereafter “pathshala”) temple education in the United States. -

Life of Mahavira As Described in the Jai N a Gran Thas Is Imbu Ed with Myths Which

T o be h a d of 1 T HE MA A ( ) N GER , T HE mu Gu ms J , A llahaba d . Lives of greatmen all remin d u s We can m our v s su m ake li e bli e , A nd n v hi n u s , departi g , lea e be d n n m Footpri ts o the sands of ti e . NGF LL W LO E O . mm zm fitm m m ! W ‘ i fi ’ mz m n C NT E O NT S. P re face Introd uction ntrod uctor remar s and th i I y k , e h storicity of M ahavira Sources of information mt o o ica stories , y h l g l — — Family relations birth — — C hild hood e d ucation marriage and posterity — — Re nou ncing the world Distribution of wealth Sanyas — — ce re mony Ke sh alochana Re solution Seve re pen ance for twe lve years His trave ls an d pre achings for thirty ye ars Attai n me nt of Nirvan a His disciples and early followers — H is ch aracte r teachings Approximate d ate of His Nirvana Appendix A PREF CE . r HE primary con dition for th e formation of a ” Nation is Pride in a common Past . Dr . Arn old h as rightly asked How can th e presen t fru th e u u h v ms h yield it , or f t re a e pro i e , except t eir ” roots be fixed in th e past ? Smiles lays mu ch ’ s ss on h s n wh n h e s s in his h a tre t i poi t , e ay C racter, “ a ns l n v u ls v s n h an d N tio , ike i di id a , deri e tre gt su pport from the feelin g th at they belon g to an u s u s h h th e h s of h ill trio race , t at t ey are eir t eir n ss an d u h u s of h great e , o g t to be perpet ator t eir is of mm n u s im an h n glory . -

Paryushana and the Festival of Forgiveness

Jainism Paryushana and the Festival of Forgiveness Paryushana and the Festival of Forgiveness Summary: The most important Jain religious observance of the year, Paryushana literally means “abiding” or “coming together.” Lasting either eight or ten days, it is a time of intensive study, reflection, and purification. It culiminates with a final day that involves confession and asking for forgiveness. Paryushana is the most important Jain religious observance of the year. For both Shvetambaras, who observe the festival over a period of eight days, and Digambaras, for whom Paryushana Parva lasts ten days, this is a time of intensive study, reflection, and purification. It takes place in the middle of the four-month rainy season in India, a time when the monks and nuns cease moving about from place to place and stay with a community. Paryushan means, literally, “abiding” or “coming together.” The monks and nuns who have to maintain fixed residence during the rainy season abide with the laity and are available to them for instruction and guidance. It is also a time when the laity take on various temporary vows of study and fasting, a spiritual intensity similar to temporary monasticism. In this respect, it bears comparison with periods of rigorous religious practice in other traditions, such as the Christian observance of Lent. Paryushana concludes with a time of confession and forgiveness for the transgressions of the previous year. In the United States, Jains often combine the two observances, with the eight days of the Shvetambara tradition followed by the ten of the Digambara tradition. It is customary for religious leaders, such as Muni Chitrabhanu, to stay at one of the Jain centers in order to be available to the laity during the period of Paryushana. -

Wednesday, June 12, 2019 6:00P.M. Brampton Room

District • Peel School Board '-"' AGENDA Instructional Programs/Curriculum Committee Wednesday, June 12, 2019 6:00p.m. Brampton Room PEEL DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD Instructional Programs/Curriculum Committee June 12,2019 Agenda June 12, 2019 - 6:00 p.m. Open Session 1. Call to Order Approval of Agenda 2. Declaration of Conflict of Interest 3. Minutes 3.1 Minutes of the Instructional Programs/Curriculum Committee Meeting held on 2019-oS-15 4. Chair•s Request for Written Questions from Committee Members 5. Notices of Motion and Petitions 6. Special Section for Receipt 6.1 Celebrating Faith and Culture Backgrounder- July, 2019 6.2 Celebrating Faith and Culture Backgrounder- August, 2019 6.3 Celebrating Faith and Culture Backgrounder - September, 2019 7. Delegations 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Reports from Officials and Staff 10.1 Smudging Guidelines 10.2 We Rise Together Year Two Update - to be distributed 1 0.3 Report of the Regional Learning Choices Programs (RLCP) Committee 11. Communications- For Action or Receipt 12. Special Section for Receipt 13. Reports from Representatives on Councils/Associations 14. Questions asked of and by Committee Members 15. Public Question Period 16. Further Business 17. Adjournment 1 May 15, 2019 Instructional Programs/Curriculum Committee:ma 3.1 PEEL DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD Minutes of a meeting of the Instructional Programs I Curriculum Committee of the Peel District School Board, held at the We Welcome the World Centre, 100 Elm Drive West, Mississauga, Ontario on Wednesday, May 15, 2019 at 18:15 hours. Members present: Member present electronically: Kathy McDonald, Chair Nokha Dakroub Susan Benjamin (18:25) Robert Crocker BalbirSohi Member absent: (apologies received) Will Davies Administration: Adrian Graham, Superintendent, Curriculum and Instruction Support Services (Executive Member) Jeffrey Blackwell, Acting Associate Director of Instructional and Equity Support Services Marina Am in, Board Reporter 1. -

Dadeechi Rushigalu & Narayana Varma

Dadeechi Rushigalu & Narayana Varma Dadeechi Rushigalu was born on Bhadrapada Shudda Astami. Dadeechi Rushigalu is considered in the Puranas as one of our earliest ancestors and he shines in this great country as the illustrious example of sacrifice for the sake of the liberation of the suffering from their distress. No sacrifice is too great for the noble-minded in this world. During Krutayuga, there was a daityas named Vrutrasura. He, associated by Kalakeyas, was attacking Devataas and made to suffer a lot. Devategalu were losing their battle against Daityaas. At that time they went to Brahmadevaru, who took them to Srihari, who recommended them to maka a weapon to destroy Vrutrasura, with the help of bones of Dadeechi Rushigalu. Dadeechi Rushigalu’s bones were very powerful with the Tapashakthi and with Narayana Varma Japa Shakthi. His bones were very very hard and unbreakable. Dadeechi Rushigalu, thereupon quietly acceded to the request of Indra. By his powers of Yoga he gave up his life so that his backbone might be utilised for making the mighty bow, Vajrayudha. In fact, Dadeechi may be regarded as the starting point of the galaxy of saints that have adorned this great country. Accordingly, all the Devatas went to Saint Dadheechi and requested him to donate his bones to them. Dadheechi accepted their request, left the body voluntarily and donated his bones to Devatas. After his death, all the Devatas collected his bones. They made a weapon named “ Vajrayudha” with the spinal bone of Dadheechi and gave it to Indra. With the help of Vajrayudha, Indra killed Vrutraasura.