Transmitting Jainism Through US Pāṭhaśāla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

Voliirw(People and Places).Pdf

Contents of Volume II People and Places Preface to Volume II ____________________________ 2 II-1. Perception for Shared Knowledge ___________ 3 II-2. People and Places ________________________ 6 II-3. Live, Let Live, and Thrive _________________ 18 II-4. Millennium of Mahaveer and Buddha ________ 22 II-5. Socio-political Context ___________________ 34 II-6. Clash of World-Views ____________________ 41 II-7. On the Ashes of the Magadh Empire _________ 44 II-8. Tradition of Austere Monks ________________ 50 II-9. Who Was Bhadrabahu I? _________________ 59 II-10. Prakrit: The Languages of People __________ 81 II-11. Itthi: Sensory and Psychological Perception ___ 90 II-12. What Is Behind the Numbers? ____________ 101 II-13. Rational Consistency ___________________ 112 II-14. Looking through the Parts _______________ 117 II-15. Active Interaction _____________________ 120 II-16. Anugam to Agam ______________________ 124 II-17. Preservation of Legacy _________________ 128 II-18. Legacy of Dharsen ____________________ 130 II-19. The Moodbidri Pandulipis _______________ 137 II-20. Content of Moodbidri Pandulipis __________ 144 II-21. Kakka Takes the Challenge ______________ 149 II-22. About Kakka _________________________ 155 II-23. Move for Shatkhandagam _______________ 163 II-24. Basis of the Discord in the Teamwork ______ 173 II-25. Significance of the Dhavla _______________ 184 II-26. Jeev Samas Gatha _____________________ 187 II-27. Uses of the Words from the Past ___________ 194 II-28. Biographical Sketches __________________ 218 II - 1 Preface to Volume II It's a poor memory that only works backwards. - Alice in Wonderland (White Queen). Significance of the past emerges if it gives meaning and context to uncertain world. -

Wednesday, June 12, 2019 6:00P.M. Brampton Room

District • Peel School Board '-"' AGENDA Instructional Programs/Curriculum Committee Wednesday, June 12, 2019 6:00p.m. Brampton Room PEEL DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD Instructional Programs/Curriculum Committee June 12,2019 Agenda June 12, 2019 - 6:00 p.m. Open Session 1. Call to Order Approval of Agenda 2. Declaration of Conflict of Interest 3. Minutes 3.1 Minutes of the Instructional Programs/Curriculum Committee Meeting held on 2019-oS-15 4. Chair•s Request for Written Questions from Committee Members 5. Notices of Motion and Petitions 6. Special Section for Receipt 6.1 Celebrating Faith and Culture Backgrounder- July, 2019 6.2 Celebrating Faith and Culture Backgrounder- August, 2019 6.3 Celebrating Faith and Culture Backgrounder - September, 2019 7. Delegations 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Reports from Officials and Staff 10.1 Smudging Guidelines 10.2 We Rise Together Year Two Update - to be distributed 1 0.3 Report of the Regional Learning Choices Programs (RLCP) Committee 11. Communications- For Action or Receipt 12. Special Section for Receipt 13. Reports from Representatives on Councils/Associations 14. Questions asked of and by Committee Members 15. Public Question Period 16. Further Business 17. Adjournment 1 May 15, 2019 Instructional Programs/Curriculum Committee:ma 3.1 PEEL DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD Minutes of a meeting of the Instructional Programs I Curriculum Committee of the Peel District School Board, held at the We Welcome the World Centre, 100 Elm Drive West, Mississauga, Ontario on Wednesday, May 15, 2019 at 18:15 hours. Members present: Member present electronically: Kathy McDonald, Chair Nokha Dakroub Susan Benjamin (18:25) Robert Crocker BalbirSohi Member absent: (apologies received) Will Davies Administration: Adrian Graham, Superintendent, Curriculum and Instruction Support Services (Executive Member) Jeffrey Blackwell, Acting Associate Director of Instructional and Equity Support Services Marina Am in, Board Reporter 1. -

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Catalogue of the Mabathi, Gujarati, Bengali, Assamese, Oriya, Pushtu, and Sindhi

C A T A L O G U E OF THE MABATHI G U JARATI BE N GAL I , , , A AME E RIYA S S S , O , P U HT A D I HI S U , N S N D MAN U S C RIP T S IN T HE L I B R A R Y OF THE I H M E B R I T S U S U M . M L M D A . J . F. , B U HAR T , PRO FES S OR O F H N D U S T AN AN D L EC T U RE R O N HIN D I AN D BEN AL AT U N V E RS TY CO L L E E L O N DO N I I , G I I I G , ; ’ AN D T EAC H E R O F BEN G AI J AT THE U N IV ERS H W OF OXFO RD . P RIN TE D B Y ORD E R OF THE TR US TE E S 2 110 1111011 S O L D A T T H E B R I T I S H MU S E U M ; AN D BY HE MESBRS L N 3 TERN TER ROW BERNARD U ARITCH I5 P CCAD L L Y W . ; AS R . O GMAN . 9 PA OS , S CO , , ; Q , , I I YD E Ho s e N N L T EN CH TR BN ER 65 CO . D R N u 1 3 BED F R R T ARD E KEGAN PAU R D , dz CO . -

The Nonhuman and Its Relationship to The

THE UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA WORLDLY AND OTHER-WORLDLY ETHICS: THE NONHUMAN AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO THE MEANINGFUL WORLD OF JAINS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES © MÉLANIE SAUCIER, OTTAWA, CANADA, 2012 For my Parents And for my Animal Companions CONTENTS Preface i Introduction 1 Definition of Terms and Summary of Chapters: Jain Identity and The Non-Human Lens 2 Methodology 6 Chapter 1 - The Ascetic Ideal: Renouncing A Violent World 10 Loka: A World Brimming with Life 11 Karma, Tattvas, and Animal Bodies 15 The Wet Soul: Non-Human Persons and Jain Karma Theory 15 Soul and the Mechanisms of Illusion 18 Jain Taxonomy: Animal Bodies and Violence 19 Quarantining Life 22 The Flesh of the Plant is Good to Eat: Pure Food for the Pure Soul 27 Jain Almsgiving: Gastro-Politics and the Non-Human Environment 29 Turning the Sacrifice Inwards: The Burning Flame of Tapas 31 Karma-Inducing Diet: Renouncing to Receive 32 Karma-Reducing Diet: Receiving to Renounce 34 Spiritual Compassion and Jain Animal Sanctuaries 38 Chapter 2 – Jainism and Ecology: Taking Jainism into the 21st Century 42 Neo-Orthodox and Eco-Conscious Jains: Redefining Jainism and Ecology 43 The Ascetic Imperative in a “Green” World 45 Sadhvi Shilapi: Treading the Mokşa-Marga in an Environmentally Conscious World 47 Surendra Bothara: Returning to True Form: A Jain Scholar‟s Perspective on the Inherent Ecological Framework of Jainism 51 “Partly Deracinated” Jainism: -

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology Jainism and Ecology Bibliography

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology Jainism and Ecology Bibliography Bibliography by: Christopher Key Chapple, Loyola Marymount University, Allegra Wiprud, and the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology Ahimsa: Nonviolence. Directed by Michael Tobias. Produced by Marion Hunt. Narrated by Lindsay Wagner. Direct Cinema Ltd. 58 min. Public Broadcasting Corporation, 1987. As the first documentary to examine Jainism, this one-hour film portrays various aspects of Jain religion and philosophy, including its history, teachers, rituals, politics, law, art, pilgrimage sites, etc. In doing so, the film studies the relevance of ancient traditions of Jainism for the present day. Ahimsa Quarterly Magazine. 1, no. 1 (1991). Bhargava, D. N. “Pathological Impact of [sic] Environment of Professions Prohibited by Jain Acaryas.” In Medieval Jainism: Culture and Environment, eds. Prem Suman Jain and Raj Mal Lodha, 103–108. New Delhi: Ashish Publishing House, 1990. Bhargava provides a chart and short explanation of the fifteen trades that both sects of Jainism forbid and that contribute to environmental pollution and pathological effects on the human body. Caillat, Colette. The Jain Cosmology. Translated by R. Norman. Basel: Ravi Kumar. Bombay: Jaico Publishing House, 1981. Chapple, Christopher Key. “Jainism and Ecology.” In When Worlds Converge: What Science and Religion Tell Us about the Story of the Universe and Our Place In It, eds. Clifford N. Matthews, Mary Evelyn Tucker, and Philip Hefner, 283-292. Chicago: Open Court, 2002. In this book chapter, Chapple provides a basic overview of the relationship of Jainism and ecology, discussing such topics as biodiversity, environmental resonances and social activism, tensions between Jainism and ecology, and the universe filled with living beings. -

Volume : 121 Issue No. : 121 Month : August, 2010

Volume : 121 Issue No. : 121 Month : August, 2010 AHIMSA TIMES ENTERS 11TH YEARS OF SERVICE TO GLOBAL JAIN COMMUNITY We are proud to enter 11th year of continuous publication & take this opportunity to thank all our Readers and Patrons for their support and guidance in our endeavor to present Jain Community from single platform. Prakash Lal Jain & Anil Jain UPCOMING FESTIVAL - PARYUSHANA Paryushana (or Paryushan) is one of the two most important festivals for the Jains, the other being Diwali. Paryushan means, literally, "abiding" or "coming together". It is also a time when the laymen following Jainism and Jain saints take on vows of religious study, meditation and fasting. Paryushana, which fall during the four month period of chaturmas is staying of the monks in one place. In popular terminology, this stay is termed chaturmasa because the rainy season is covered during this period. Paryushana is initiated from fourth or fifth day of the shukla phase of the Bhadrapada month. In the scriptures it is described that Lord Mahavira used to start Paryushana on Bhadrapada paksha panchami. After Mahavir, nearly 150 years Jain Samvatsari was shifted to Chaturthi (4th day of Bhadrapada of Shukla phase. Since 2200 years Jains follows Chaturthi. The date of commencement of the Paryushana festival, which lasts for eight days for shwetambar and ten days for digambar sect followers is from Bhadrapada Shukla Chaturthi for murti-pujak sect and panchami for shwetambar sthanakwasi and terapanth sects, as well as for Digambar sect. The last day of Paryushan is called ‘Samvarsari’Recently there has been an attempt standardize the date. -

Chaturmas 2016 Begins

Ju ly , 201 6 Vol. No. 192 Ahimsa Times in World Over + 100000 The Only Jain E-Magazine Community Service for 14 Continuous Years Readership CHATURMAS 2016 BEGINS Chaturmas is a holy period of four months (July to October), beginning on Shayani Ekadashi the eleventh day of the first bright half, Shukla Paksha, of Ashadh (fourth month of the Hindu lunar calendar until Prabodhini Ekadashi, the eleventh day of the first bright half of Kartik (eighth month of the Hindu lunar calendar) in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. Chaturmas is reserved for penance, austerities, fasting, bathing in holy rivers and religious observances for all. Devotees resolve to observe some form of vow, be it of silence or abstaining from a favourite food item, or having only a single meal in a day. In Jainism this practice is collectively known as Varshayog and is prescribed for Jain monasticism. Wandering monks such as mendicants and ascetics in Jainism, believed that during the rain season, countless bugs, insects and tiny creatures that cannot be seen in the naked eye would be produced massively. Therefore, these monks reduce the amount of harm they do to other creatures so they opt to stay in a village for the four months to incur minimal harm to other lives. These monks, who generally do not stay in one place for long, observe their annual 'Rains Retreat' during this period, by living in one place during the entire period amidst lay people, observing a vow of silence, meditation, fasting and other austerities, and also giving religious discourses to the local public. -

Courses in Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2013 Issue 8 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Jaina Logic: Programme 7 Jaina Logic: Abstracts 10 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2012 12 SOAS Workshop 2014: Jaina Hagiography and Biography 13 Jaina Studies at the AAR 2012 16 The Intersections of Religion, Society, Polity, and Economy in Rajasthan 18 DANAM 2012 19 Debate, Argumentation and Theory of Knowledge in Classical India: The Import of Jainism 21 The Buddhist and Jaina Studies Conference in Lumbini, Nepal Research 24 A Rare Jaina-Image of Balarāma at Mt. Māṅgī-Tuṅgī 29 The Ackland Art Museum’s Image of Śāntinātha 31 Jaina Theories of Inference in the Light of Modern Logics 32 Religious Individualisation in Historical Perspective: Sociology of Jaina Biography 33 Daulatrām Plays Holī: Digambar Bhakti Songs of Springtime 36 Prekṣā Meditation: History and Methods Jaina Art 38 A Unique Seven-Faced Tīrthaṅkara Sculpture at the Victoria and Albert Museum 40 Aspects of Kalpasūtra Paintings 42 A Digambar Icon of the Goddess Jvālāmālinī 44 Introducing Jain Art to Australian Audiences 47 Saṃgrahaṇī-Sūtra Illustrations 50 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund Publications 51 Johannes Klatt’s Jaina-Onomasticon: The Leverhulme Trust 52 The Pianarosa Jaina Library 54 Jaina Studies Series 56 International Journal of Jaina Studies 57 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 57 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 58 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 58 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 59 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover Gautama Svāmī, Śvetāmbara Jaina Mandir, Amṛtsar 2009 Photo: Ingrid Schoon 2 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christopher Key Chapple Dr Hawon Ku Professor J. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

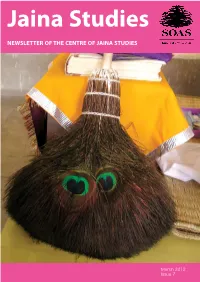

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2012 Issue 7 CoJS Newsletter • March 2012 • Issue 7 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Programme 7 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Abstracts 11 The Paul Thieme Lectureship in Prakrit 12 Jaina Narratives: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2011 15 SOAS Workshop 2013: Jaina Logic 16 Old Voices, New Visions: Jains in the History of Early Modern India at the AAS 18 How Do You ‘Teach’ Jainism? 20 Sanmarga: International Conference on the Influence of Jainism in Art, Culture & Literature 22 Jaina Studies Section at the 15th World Sanskrit Conference 24 Jiv Daya Foundation: Jainism Heritage Preservation Effort 24 Jaina Studies Certificate at SOAS Research 25 Stūpa as Tīrtha: Jaina Monastic Funerary Monuments 28 Peacock-Feather Broom (Mayūra-Picchī): Jaina Tool for Non-Violence 30 A Digambar Icon of 24 Jinas at the Ackland Art Museum 34 Life and Works of the Kharatara Gaccha Monk Jinaprabhasūri (1261-1333) 37 Jains in the Multicultural Mughal Empire 40 Fragile Virtue: Interpreting Women’s Monastic Practice in Early Medieval India Jaina Art 42 The Elegant Image: Bronzes at the New Orleans Museum of Art 45 Notes on Nudity in Digambara Jaina Art 47 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund 48 Continuing the Tradition: Jaina Art History in Berlin Publications 49 Jaina Studies Series 51 International Journal of Jaina Studies 52 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 52 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Prakrit Studies 53 Prakrit Courses at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 54 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 54 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 55 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover The Peacock-Feather Broom (mayūra-picchī) of Āryikā Muktimatī Mātājī, in the Candraprabhu Digambara Jain Baṛā Mandira, in Bārābaṅkī/U.P. -

46519598.Pdf

AUCTIONING THE DREAMS: ECONOMY, COMMUNITY AND PHILANTHROPY IN A NORTH INDIAN CITY ROGER GRAHAM SMEDLEY A thesis submitted for a Ph.D. Degree, London School of Economics, University of London 199 3 UMI Number: U615785 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615785 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Th e s e s F 722s The debate on Indian entrepreneurship largely revolves around Weber’s Protestant ethic thesis, its applicability to non-western countries and his comparative study of the sub continent’s religions. However, India historically possessed a long indigenous entrepreneurial tradition which was represented by a number of business communities. The major hypothesis of this dissertation is that the socio-cultural milieu and practices of certain traditional business communities generates entrepreneurial behaviour, and this behaviour is compatible with contemporary occidental capitalism. This involves an analysis of the role of entrepreneurship and business communities in the Indian economy; specifically, a Jain community in the lapidary industry of Jaipur: The nature of business networks - bargaining, partnerships, credit, trust and the collection of information - and the identity of the family with the business enterprise, concluding with a critique of dichotomous models of the economy.