Roots, Routes, and Routers: Social and Digital Dynamics in the Jain Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

Transmitting Jainism Through US Pāṭhaśāla

Transmitting Jainism through U.S. Pāṭhaśāla Temple Education, Part 2: Navigating Non-Jain Contexts, Cultivating Jain-Specific Practices and Social Connections, Analyzing Truth Claims, and Future Directions Brianne Donaldson Abstract In this second of two articles, I offer a summary description of results from a 2017 nationwide survey of Jain students and teachers involved in pāṭha-śāla (hereafter “pathshala”) temple education in the United States. In these two essays, I provide a descriptive overview of the considerable data derived from this 178-question survey, noting trends and themes that emerge therein, in order to provide a broad orientation before narrowing my scope in subsequent analyses. In Part 2, I explore the remaining survey responses related to the following research questions: (1) How does pathshala help students/teachers navigate their social roles and identities?; (2) How does pathshala help students/teachers deal with tensions between Jainism and modernity?; (3) What is the content of pathshala?, and (4) How influential is pathshala for U.S. Jains? Key words: Jainism, pathshala, Jain education, pedagogy, Jain diaspora, minority, Jains in the United States, intermarriage, pluralism, future of Jainism, second- and third-generation Jains, Young Jains of America, Jain orthodoxy and neo-orthodoxy, Jainism and science, Jain social engagement Transnational Asia: an online interdisciplinary journal Volume 2, Issue 1 https://transnationalasia.rice.edu https://doi.org/10.25613/3etc-mnox 2 Introduction In this paper, the second of two related articles, I offer a summary description of results from a 2017 nationwide survey of Jain students and teachers involved in pāṭha-śāla (hereafter “pathshala”) temple education in the United States. -

Voliirw(People and Places).Pdf

Contents of Volume II People and Places Preface to Volume II ____________________________ 2 II-1. Perception for Shared Knowledge ___________ 3 II-2. People and Places ________________________ 6 II-3. Live, Let Live, and Thrive _________________ 18 II-4. Millennium of Mahaveer and Buddha ________ 22 II-5. Socio-political Context ___________________ 34 II-6. Clash of World-Views ____________________ 41 II-7. On the Ashes of the Magadh Empire _________ 44 II-8. Tradition of Austere Monks ________________ 50 II-9. Who Was Bhadrabahu I? _________________ 59 II-10. Prakrit: The Languages of People __________ 81 II-11. Itthi: Sensory and Psychological Perception ___ 90 II-12. What Is Behind the Numbers? ____________ 101 II-13. Rational Consistency ___________________ 112 II-14. Looking through the Parts _______________ 117 II-15. Active Interaction _____________________ 120 II-16. Anugam to Agam ______________________ 124 II-17. Preservation of Legacy _________________ 128 II-18. Legacy of Dharsen ____________________ 130 II-19. The Moodbidri Pandulipis _______________ 137 II-20. Content of Moodbidri Pandulipis __________ 144 II-21. Kakka Takes the Challenge ______________ 149 II-22. About Kakka _________________________ 155 II-23. Move for Shatkhandagam _______________ 163 II-24. Basis of the Discord in the Teamwork ______ 173 II-25. Significance of the Dhavla _______________ 184 II-26. Jeev Samas Gatha _____________________ 187 II-27. Uses of the Words from the Past ___________ 194 II-28. Biographical Sketches __________________ 218 II - 1 Preface to Volume II It's a poor memory that only works backwards. - Alice in Wonderland (White Queen). Significance of the past emerges if it gives meaning and context to uncertain world. -

JAINISM Early History

111111xxx00010.1177/1111111111111111 Copyright © 2012 SAGE Publications. Not for sale, reproduction, or distribution. J Early History JAINISM The origins of the doctrine of the Jinas are obscure. Jainism (Jinism), one of the oldest surviving reli- According to tradition, the religion has no founder. gious traditions of the world, with a focus on It is taught by 24 omniscient prophets, in every asceticism and salvation for the few, was confined half-cycle of the eternal wheel of time. Around the to the Indian subcontinent until the 19th century. fourth century BCE, according to modern research, It now projects itself globally as a solution to the last prophet of our epoch in world his- world problems for all. The main offering to mod- tory, Prince Vardhamāna—known by his epithets ern global society is a refashioned form of the Jain mahāvīra (“great hero”), tīrthaṅkāra (“builder of ethics of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and nonpossession a ford” [across the ocean of suffering]), or jina (aparigraha) promoted by a philosophy of non- (spiritual “victor” [over attachment and karmic one-sidedness (anekāntavāda). bondage])—renounced the world, gained enlight- The recent transformation of Jainism from an enment (kevala-jñāna), and henceforth propagated ideology of world renunciation into an ideology a universal doctrine of individual salvation (mokṣa) for world transformation is not unprecedented. It of the soul (ātman or jīva) from the karmic cycles belongs to the global movement of religious mod- of rebirth and redeath (saṃsāra). In contrast ernism, a 19th-century theological response to the to the dominant sacrificial practices of Vedic ideas of the European Enlightenment, which West- Brahmanism, his method of salvation was based on ernized elites in South Asia embraced under the the practice of nonviolence (ahiṃsā) and asceticism influence of colonialism, global industrial capital- (tapas). -

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Jain Award Boy Scout Workbook Green Stage 2

STAGE 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. About the Jain Award: Stage 2 2. About Yourself 3. Part I Word 4. Part II Worship 5. Part III Witness 6. Jain Religion Information for Boy Scouts of America 7. Application Form for the Jain Medal Award 2 ABOUT THE JAIN AWARD PLAN STAGE 2 WORD: You will with your parents and spiritual leader meet regularly to complete all the requirements History of Jainism-Lives of Tirthankars: for this award. Mahavir Adinath Parshvanath RECORD Jain Philosophy Significance of Jain Symbols: Ashtamanga As you continue through this workbook, record and others the information as indicated. Once finished Four types of defilement (kashäy): your parents and spiritual leader will review anger ego and then submit for the award. greed deceit The story of four daughters-in-law (four types of spiritual aspirants) Five vows (anuvrats) of householders Jain Glossary: Ätmä, Anekäntväd, Ahinsä, Aparigrah, Karma, Pranäm, Vrat,Dhyän. WORSHIP: Recite Hymns from books: Ärati Congratulations. You may now begin. Mangal Deevo Practices in Daily Life: Vegetarian diet Exercise Stay healthy Contribute charity (cash) and volunteer (kind) Meditate after waking-up and before bed WITNESS: Prayers (Stuties) Chattäri mangala Darshanam dev devasya Shivamastu sarvajagatah Learn Temple Rituals: Nissihi Pradakshinä Pranäm Watch ceremonial rituals (Poojä) in a temple 3 ABOUT YOURSELF I am _____________________years old My favorite activities/hobbies are: ______________________________________ This is my family: ______________________________________ ______________________________________ -

Teacher Training in Dharmic Studies

Teacher Training in Dharmic Studies Bal Ram Singh, Ph.D. Director, Center for Indic Studies University of Masachusetts Dartmouth Phone-508-999-8588 Fax-508-999-8451 [email protected] Organizers and presenters traditional Indian dress, along with Uberoi Foundations officials on August 18, 2010 Executive Summary phy. Presentations on each of the traditions were carried out by practicing scholars, except in case of Buddhism The Pilot project initiated after the first meeting of the for which we could not get scholars from the tradition. Uberoi Foundation in Orlando, October, 2009, by Ra- jiv Malhotra of Infinity Foundation and Bal Ram Singh The training program on each topic included slide presen- of UMass Dartmouth, was carried out with funding tation, hands-on activities, demonstrations, and lesson from Uberoi Foundation. With assistance of a national plan discussions. In addition, two documentaries, Yoga Advisory Committee (AC) and local Implementation unveiled and Raaga Unveiled were screened with commen- Advisory Group (IAG), the program was developed in taries from its producer, Mrs.Geeta Desai. Evening pro- spring of 2010 with plans to develop teaching material grams included discussion on Indian culture, music, dress, on four Dharmic traditions (Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, and family, etc., including trial of Indian dress by the trainees. Sikh) by experts in the field. The written material was re- viewed by experienced school level teachers, and at least Interactive sessions were held with representatives of Uber- some of the feedback was incorporated in the written oi Foundations, practioners of traditions, and with a facul- material before the latter was provided to the trainees. -

Nay Or Jain Nyay 2: Logic of Atheism of Jain Dharm

Philosophy Study, February 2016, Vol. 6, No. 2, 69-87 doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2016.02.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Nay or Jain Nyay 2: Logic of Atheism of Jain Dharm Mahendra Kumar Jain, Agam Jain University of Delaware Ethos and logos of the Jain thought and practice (world view) is based on reality perceived by senses. Atheistic roots of Jain Dharm have nourished growth, maintained viability and vitality, and kept it relevant for over the last five millennia. Unlike Judeo-Christian-Islam or Brahminical faith, it does not rely on omniscient supreme or god. Its atheistic and anti-theistic thrust is generally known, yet its followers do not call themselves Nastik (non-believers). They emphasize action-consequence relations as guide for successful behaviors with ethical conduct. The basis of their arguments follows from the Jain logic (Saptbhangi Syad Nay) of evidence based inference with multiple orthogonal affirmed assertions (Jain 2011). It conserves information by acknowledging the remaining doubt in an inference. It does not assume binary complementation to force closure for deduction with incomplete knowledge which leads to self-reference and loss of information. This approach offers a rational and practical alternative to conundrum of western atheism even though its arguments are logical and consistent with available evidence. It also obviates need to extract religious morality from social mores. Objective truth and knowledge of established generalizations is necessary but not sufficient for subjective searches to shape desires and for what the future ought to be. Keywords: Atheism, Mahaveer (Mahavira), Jainism, Jains, Omniscience, Nay, Jain Nyay, Nyaya, Tirthankar, Arhat, Arihant, conflict resolution, nonviolence, truthfulness, Buddha (Buddh), nothingness (Shoonyata), limitations of binary logic, logic of inference, Saptbhangi Syad Nay 1. -

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology Jainism and Ecology Bibliography

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology Jainism and Ecology Bibliography Bibliography by: Christopher Key Chapple, Loyola Marymount University, Allegra Wiprud, and the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology Ahimsa: Nonviolence. Directed by Michael Tobias. Produced by Marion Hunt. Narrated by Lindsay Wagner. Direct Cinema Ltd. 58 min. Public Broadcasting Corporation, 1987. As the first documentary to examine Jainism, this one-hour film portrays various aspects of Jain religion and philosophy, including its history, teachers, rituals, politics, law, art, pilgrimage sites, etc. In doing so, the film studies the relevance of ancient traditions of Jainism for the present day. Ahimsa Quarterly Magazine. 1, no. 1 (1991). Bhargava, D. N. “Pathological Impact of [sic] Environment of Professions Prohibited by Jain Acaryas.” In Medieval Jainism: Culture and Environment, eds. Prem Suman Jain and Raj Mal Lodha, 103–108. New Delhi: Ashish Publishing House, 1990. Bhargava provides a chart and short explanation of the fifteen trades that both sects of Jainism forbid and that contribute to environmental pollution and pathological effects on the human body. Caillat, Colette. The Jain Cosmology. Translated by R. Norman. Basel: Ravi Kumar. Bombay: Jaico Publishing House, 1981. Chapple, Christopher Key. “Jainism and Ecology.” In When Worlds Converge: What Science and Religion Tell Us about the Story of the Universe and Our Place In It, eds. Clifford N. Matthews, Mary Evelyn Tucker, and Philip Hefner, 283-292. Chicago: Open Court, 2002. In this book chapter, Chapple provides a basic overview of the relationship of Jainism and ecology, discussing such topics as biodiversity, environmental resonances and social activism, tensions between Jainism and ecology, and the universe filled with living beings. -

Concept of God in Jainism

Concept of God in Jainism Jainism believes that the universe and all its substances or entities are eternal. It has no beginning or end with respect to time. The universe runs on its own accord by its own cosmic laws. All the substances change or modify their forms continuously. Nothing can be destroyed or created in the universe. There is no need for someone to create or manage the affairs of the universe. Hence Jainism does not believe in God as a creator, survivor, and destroyer of the universe. However, Jainism does believe in God, not as a creator, but as a perfect being. When a person destroys all his karmas, he becomes a liberated soul. He resides in a perfect blissful state in Moksha. He possesses infinite knowledge, infinite vision, infinite power, and infinite bliss. This living being is a God of the Jain religion. Every living being has the potential to become God. Hence Jains do not have one God, but Jain Gods are innumerable and their number is continuously increasing as more living beings attain liberation. Jains believe that since the beginning of time every living being (soul) because of its ignorance, is attached with karma. The main purpose of the religion is to remove this karma through self-knowledge and become a liberated soul. There are many types of karma. However, they are broadly classified into the following eight categories: 1. Mohniya karma It generates delusion in the soul in regard to its own true nature, and makes it identify itself with other external substances. 2. -

Courses in Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2013 Issue 8 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Jaina Logic: Programme 7 Jaina Logic: Abstracts 10 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2012 12 SOAS Workshop 2014: Jaina Hagiography and Biography 13 Jaina Studies at the AAR 2012 16 The Intersections of Religion, Society, Polity, and Economy in Rajasthan 18 DANAM 2012 19 Debate, Argumentation and Theory of Knowledge in Classical India: The Import of Jainism 21 The Buddhist and Jaina Studies Conference in Lumbini, Nepal Research 24 A Rare Jaina-Image of Balarāma at Mt. Māṅgī-Tuṅgī 29 The Ackland Art Museum’s Image of Śāntinātha 31 Jaina Theories of Inference in the Light of Modern Logics 32 Religious Individualisation in Historical Perspective: Sociology of Jaina Biography 33 Daulatrām Plays Holī: Digambar Bhakti Songs of Springtime 36 Prekṣā Meditation: History and Methods Jaina Art 38 A Unique Seven-Faced Tīrthaṅkara Sculpture at the Victoria and Albert Museum 40 Aspects of Kalpasūtra Paintings 42 A Digambar Icon of the Goddess Jvālāmālinī 44 Introducing Jain Art to Australian Audiences 47 Saṃgrahaṇī-Sūtra Illustrations 50 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund Publications 51 Johannes Klatt’s Jaina-Onomasticon: The Leverhulme Trust 52 The Pianarosa Jaina Library 54 Jaina Studies Series 56 International Journal of Jaina Studies 57 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 57 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 58 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 58 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 59 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover Gautama Svāmī, Śvetāmbara Jaina Mandir, Amṛtsar 2009 Photo: Ingrid Schoon 2 CoJS Newsletter • March 2013 • Issue 8 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christopher Key Chapple Dr Hawon Ku Professor J. -

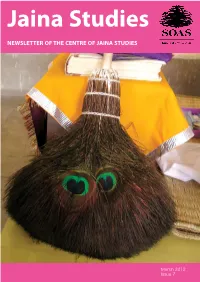

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2012 Issue 7 CoJS Newsletter • March 2012 • Issue 7 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Programme 7 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Abstracts 11 The Paul Thieme Lectureship in Prakrit 12 Jaina Narratives: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2011 15 SOAS Workshop 2013: Jaina Logic 16 Old Voices, New Visions: Jains in the History of Early Modern India at the AAS 18 How Do You ‘Teach’ Jainism? 20 Sanmarga: International Conference on the Influence of Jainism in Art, Culture & Literature 22 Jaina Studies Section at the 15th World Sanskrit Conference 24 Jiv Daya Foundation: Jainism Heritage Preservation Effort 24 Jaina Studies Certificate at SOAS Research 25 Stūpa as Tīrtha: Jaina Monastic Funerary Monuments 28 Peacock-Feather Broom (Mayūra-Picchī): Jaina Tool for Non-Violence 30 A Digambar Icon of 24 Jinas at the Ackland Art Museum 34 Life and Works of the Kharatara Gaccha Monk Jinaprabhasūri (1261-1333) 37 Jains in the Multicultural Mughal Empire 40 Fragile Virtue: Interpreting Women’s Monastic Practice in Early Medieval India Jaina Art 42 The Elegant Image: Bronzes at the New Orleans Museum of Art 45 Notes on Nudity in Digambara Jaina Art 47 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund 48 Continuing the Tradition: Jaina Art History in Berlin Publications 49 Jaina Studies Series 51 International Journal of Jaina Studies 52 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 52 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Prakrit Studies 53 Prakrit Courses at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 54 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 54 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 55 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover The Peacock-Feather Broom (mayūra-picchī) of Āryikā Muktimatī Mātājī, in the Candraprabhu Digambara Jain Baṛā Mandira, in Bārābaṅkī/U.P.