Armstrong-Language Change in Context 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions

http://lexikos.journals.ac.za; https://doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1604 Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions: A Slovene–English Case Study Marjeta Vrbinc, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Danko Šipka, School for International Letters and Cultures, Arizona State University, Tempe Campus, USA ([email protected]) and Alenka Vrbinc, School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Abstract: This article presents and discusses the findings of a study conducted with the users of Slovene and American monolingual dictionaries. The aim was to investigate how native speakers of Slovene and American English interpret select normative labels in monolingual dictionaries. The data were obtained by questionnaires developed to elicit monolingual dictionary users' attitudes toward normative labels and the effects the labels have on dictionary users. The results show that a higher level of prescriptivism in the Slovene linguistic culture is reflected in the Slovene respon- dents' perception of the labels (for example, a stronger effect of the normative labels, a higher approval for the claim about usefulness of the labels, a considerably lower general level of accep- tance for the standard language) when compared with the American respondents' perception, since the American linguistic culture tends to be more descriptive. However, users often seek answers to their linguistic questions in dictionaries, which means that they expect at least a certain degree of normativity. Therefore, a balance between descriptive and prescriptive approaches should be found, since both of them affect the users. Keywords: GENERAL MONOLINGUAL DICTIONARY, PRESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVITY, DESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVE LABELS, PRIMARY EXCLUSION LABELS, SECONDARY EXCLUSION LABELS, USE OF LABELS, USEFULNESS OF LABELS, (UN)LABELED ENTRIES Opsomming: Normatiewe etikette in twee leksikografiese tradisies: 'n Sloweens–Engelse gevallestudie. -

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

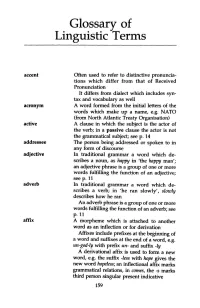

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

(Esp): Nursing in the Us Hospital

ENGLISH FOR SPECIFIC PURPOSES (ESP): NURSING IN THE U.S. HOSPITAL ____________ A Project Presented To the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Teaching International Languages ____________ by © Laura Medlin 2009 Fall 2009 ENGLISH FOR SPECIFIC PURPOSES (ESP): NURSING IN THE U.S. HOSPITAL A Project by Laura Medlin Fall 2009 APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE, INTERNATIONAL, AND INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES: Mark J. Morlock, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Hilda Hernández, Ph.D. Hilda Hernández, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator Paula Selvester, Ph.D. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this project may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii DEDICATION To all my hard-working brothers and sisters, in hospitals everywhere. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr. Hilda Hernandez and Dr. Paula Selvester. v TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Publication Rights ...................................................................................................... iii Dedication .................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgments...................................................................................................... v List of Tables ............................................................................................................. ix Abstract -

Philology Colloquial Words and Expressions. Slang

Web of Scholar ISSN 2518-167X PHILOLOGY COLLOQUIAL WORDS AND EXPRESSIONS. SLANG. STYLES IN WRITTEN COMMUNICATION. BUSINESS COMMUNICATION Docent, PhD Mesimova Lale Azerbaijan, Baku, Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received 26 January 2018 This present article shed lights on the importance of taking into consideration the Accepted 12 February 2018 consistent usage of colloquial words ,expressions ,slangs ,styles as well as their Published 12 March 2018 excessive role in written communication Colloquial words basically referred to "colloqualism" are words that are common in everyday usage, unconstrained KEYWORDS conversation, in comparison with formal speech or academic writing. Colloqualism, Colloquialisms are not substandard or illiterate speech says they are rather slang, idioms, conversational phrases, and informal speech patterns often common to a argot, particular region or nationality. Colloquial, casual, and formal writing are three upper colloquial, common styles that carry their own particular sets of expectations.The type of common colloquial, style that is going to be chosen ought to be according to the audience, and often low colloquial, a communication that a man is going to preside over .As a general rule, external euphemisms, communications tend to be more formal. Slang is the use of informal words and casual language, expressions that are not considered standard in the speaker's dialect or language. lexical varieties Slang is also the misuse of words and phrases that are incorrect or illogical when taken in the literal sense.The term slang is frequently used on the purpose of denoting a large variety of vocabulary strata that consists either of newly coined words and phrases or of current words employed in special meaning - school slang, sport slang ,newspaper slang. -

Download (394Kb)

CHAPTER II REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE In this chapter, researcher will explain about related and relevant theories that become the main discussion in this research. This chapter covers language varieties, types of language varieties, colloquial, types of colloquial, teaching listening, and Ariana Grande “Thank U, Next” album. 2.1 Language Varieties Language is not uniform or constant, even though English has been established as international language, it does not mean people have same rule, same dialect, and same way to use that language. The appearance of language varieties is caused by the variety of linguistic styles used by the society and it will continue to grow as the times develop. According to Nordquist (2019), Language variety is a general term for any distinctive form of a language or linguistic expression. Linguists commonly use language variety as a cover term for any of the overlapping subcategories of a language. Alluding to Wardhaugh and Fuller (2015), a ‘language’ is considered an overarching category containing dialects, it is also often seen as synonymous with the standard dialect; yet a closer examination of the standard reveals that it is a value-laden abstraction, not an objectively defined linguistic variety. Further, every language has a range of regional dialects, social dialects, styles, registers, and genres. Those aspects might cause variations in language. 6 2.2 Type of Language Varieties Several points of view have been taken to analyze and classify the language variety. In line with this, the varieties can be divided into two types, they are individual and societal language varieties. Jendra (2012), divides into many types of language variety, but the researcher only takes some points which have close relation to this research. -

The Representation of Central-Southern Italian Dialects and African-American Vernacular English in Translation: Issues of Cultural Transfers and National Identity

THE REPRESENTATION OF CENTRAL-SOUTHERN ITALIAN DIALECTS AND AFRICAN-AMERICAN VERNACULAR ENGLISH IN TRANSLATION: ISSUES OF CULTURAL TRANSFERS AND NATIONAL IDENTITY A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Adriana Di Biase August, 2015 © Copyright by Adriana Di Biase 2015 All Rights Reserved ii Dissertation written by Adriana Di Biase Ph.D., Kent State University – Kent, United States, 2015 M.A., Università degli Studi di Bari “Aldo Moro” – Bari, Italy, 2008 M.A., Scuola Superiore per Interpreti e Traduttori, Gregorio VII – Rome, Italy, 2002 B.A., Università degli Studi “Gabriele D’Annunzio” – Chieti-Pescara, Italy, 2000 Approved by ______________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Françoise Massardier-Kenney ______________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Brian J. Baer ______________________________, Carol Maier ______________________________, Gene R. Pendleton ______________________________, Babacar M’Baye Accepted by ______________________________, Chair, Modern and Classical Language Studies Keiran J. Dunne ______________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences James L. Blank iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... vii LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................ -

A Study of English Translation of Colloquial Expressions in Two Translations of Jamalzadeh: Once Upon a Time and Isfahan Is Half the World

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 1011-1021, September 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0805.24 A Study of English Translation of Colloquial Expressions in Two Translations of Jamalzadeh: Once Upon a Time and Isfahan Is Half the World Elham Jalalpour English Department, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Iran Hossein Heidari Tabrizi English Department, Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, Iran Abstract—The purpose of this study was to explore the translation of one of the sub-categories of culture- bound items that is colloquial and slang expressions from Persian to English in two works by Jamalzadeh, Yeki Bud, Yeki Nabud translated by Moayyed & Sprachman and Sar o Tah e Yek Karbas translated by Heston. Applying Newmark’s (1988b) framework, the type and frequency of translation procedures applied by translators as well as the effectiveness of the translators in preserving the level of colloquialism of source texts were determined. The results of this descriptive study revealed that the translators had applied 6 procedures: synonymy (%51), paraphrase (%26.5), literal (%8.5), descriptive equivalent (%2.5 ), couplet (%2) , shift (%1), omission (%5) and mistranslation (%3.5). As for maintaining the informal style of the source texts, the co- translators of the book of Yeki, Sprachman (native English translator) and Moayyed (native Persian translator) have been more consistent and successful in preserving the tone of the original text than Heston (native English translator of Sar). This success can be partly justified by the acquaintance of Moayyed with Persian language and culture making the correct recognition and translation of expressions possible. -

A Testbed for Morphological Transformation of Indonesian Colloquial Words

IndoCollex: A Testbed for Morphological Transformation of Indonesian Colloquial Words Haryo Akbarianto Wibowo∗ Made Nindyatama Nityasya∗ Afra Feyza Akyurek¨ ? Suci Fitriany∗ Alham Fikri Aji∗ Radityo Eko Prasojo∗• Derry Tanti Wijaya? ∗ Kata.ai Research Team, Jakarta, Indonesia ? Department of Computer Science, Boston University • Faculty of Computer Science, Universitas Indonesia fharyo,made,suci,aji,[email protected] Abstract more commonly a morphological transformation2 of their standard counterparts.3 Despite these evolv- Indonesian language is heavily riddled with ing lexicons, existing research on Indonesian word colloquialism whether in written or spoken normalization has largely (1) relied on creating forms. In this paper, we identify a class of Indonesian colloquial words that have un- static informal dictionaries (Le et al., 2016), render- dergone morphological transformations from ing normalization of unseen words impossible, and their standard forms, categorize their word for- (2) for the specific task of sentiment analysis (Le mations, and propose a benchmark dataset of et al., 2016) or machine translation (Guntara et al., Indonesian Colloquial Lexicons (IndoCollex) 2020), with no direct implication to word normal- consisting of informal words on Twitter ex- ization in general. Given the obvious utility of cre- pertly annotated with their standard forms and ating NLP systems that can normalize Indonesian their word formation types/tags. We evalu- informal data, we believe that the bottleneck is that ate several models for character-level trans- duction to perform morphological word nor- there is no standard open testbed for researchers malization on this testbed to understand their and developers of such system to test the effective- failure cases and provide baselines for future ness of their models to these colloquial words. -

STUDENT SLANG Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY IN BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE STUDENT SLANG Diploma thesis Brno 2009 Written by: Bc. Veronika Burdová Supervisor: Mgr. Radek Vogel, Ph.D. I declare that I worked on the following thesis on my own and that I used all the sources mentioned in the bibliography. [2] Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Mgr. Radek Vogel, Ph.D. for his comments on my work, for his kind help and valuable advice that he provided me. [3] TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 6 1. Sociolinguistic analysis: an English-Czech comparison 8 1.1 Slang, jargon and argot 8 1.2 Definition of slang – the Czech sociolinguistic approach 9 1.3 Definition of slang – the English sociolinguistic approach 11 1.4 Definition and characteristics of student slang 13 2. Linguistic analysis of slang: an English-Czech comparison 14 2.1 Productive Czech and English slang wordformation processes 14 2.2 The morphological and grammatical properties of slang 15 2.2.1 Compounding of slang words 16 2.2.2 Affixation of slang words 17 2.2.3 Functional shift of slang words 18 2.2.4 Shortening – acronyms, clipping, blending of slang words 19 2.3 The phonological properties of slang 22 2.4 The sociological properties of slang 23 3. Classification of slang within non-standard varieties 25 3.1 Specific, general slang 25 3.2 Slang vs. dialect 26 3.3 Slang vs. vernacular language 27 3.4 Slang vs. colloquial language 27 3.5 Comparison of the slang, dialect and vernacular text 28 4. -

Harlytska Tetiana SUBSTANDARD VOCABULARY in the SYSTEM of URBAN COMMUNICATION

Harlytska Tetiana SUBSTANDARD VOCABULARY IN THE SYSTEM OF URBAN COMMUNICATION Harlytska Tetiana1 DOI: dx.doi.org/10.30525/978-9934-571-30-5_14 Abstract. The article is devoted to substandard elements which are considered as one of the components in the system of urban forms of communication. The Object of our research is substandard vocabulary, the Subject is structural characteristics of the modern city language, the Purpose of the study is to define the main types of substandard vocabu- lary and their role in the system of urban communication. The theoretical base of our research includes the scientific works of native and foreign linguists, which are devoted to urban linguistics (B. Larin, M. Makovskyi, V. Labov, T. Yerofeieva, L. Pederson, R. McDavid, O. Horbach, L. Stavytska, Y. Stepanov, S. Martos). Different lexical and phraseolog- ical units, taken from the Ukrainian, Russian and American Dictionaries of slang and jargon, serve as the material of our research. The main com- ponents of the city language include literary language, territorial dialects, different intermediate transitional types, which are used in the colloquial everyday communication but do not have territorial limited character, and social dialects. The structural characteristics, proposed in the arti- cle, demonstrate the variety and correlation of different subsystems of the city language. Today peripheral elements play the main role in the city communication. They are also called substandard, non-codified, marginal, non-literary elements or the jargon styles of communication. Among sub- standard elements of the city language the most important are social dia- lects, which include such subsystems as argot, jargon and slang. -

VERNACULAR: Synonyms and Related Words. What Is Another

Need another word that means the same as “vernacular”? Find 22 synonyms and 30 related words for “vernacular” in this overview. Table Of Contents: Vernacular as a Noun Definitions of "Vernacular" as a noun Synonyms of "Vernacular" as a noun (20 Words) Usage Examples of "Vernacular" as a noun Vernacular as an Adjective Definitions of "Vernacular" as an adjective Synonyms of "Vernacular" as an adjective (2 Words) Usage Examples of "Vernacular" as an adjective Associations of "Vernacular" (30 Words) The synonyms of “Vernacular” are: argot, cant, jargon, lingo, patois, slang, everyday language, native speech, common parlance, non-standard language, idiom, dialect, phraseology, terms, expressions, words, language, parlance, vocabulary, nomenclature, common, vulgar Vernacular as a Noun Definitions of "Vernacular" as a noun According to the Oxford Dictionary of English, “vernacular” as a noun can have the following definitions: The terminology used by people belonging to a specified group or engaging in a specialized activity. A characteristic language of a particular group (as among thieves. The everyday speech of the people (as distinguished from literary language. Architecture concerned with domestic and functional rather than public or monumental buildings. The language or dialect spoken by the ordinary people in a particular country or GrammarTOP.com region. Synonyms of "Vernacular" as a noun (20 Words) The jargon or slang of a particular group or class. argot Teenage argot. Stock phrases that have become nonsense through endless cant repetition. Thieves cant. common parlance A piece of open land for recreational use in an urban area. The usage or vocabulary that is characteristic of a specific dialect group of people. -

HIV/AIDS Prevention Bilingual Glossary English ↔ Spanish

HIV/AIDS Prevention Glosario bilingüe Bilingual Glossary de prevención del VIH/SIDA English ↔ Spanish Español ↔ Inglés First Edition 2009 Primera edición 2009 Office of Minority Health Resource Center (OMHRC) Capacity Building Division www.omhrc.gov Center for AIDS Prevention Studies (CAPS) University of California, San Francisco www.caps.ucsf.edu Table of Contents Índice Pg. Introduction Introducción 4 Disclaimer Descargo de responsabilidad 7 About the glossary Sobre este glosario 8 Glossary Work Group Grupo de trabajo del glosario 8 Acknowledgments Reconocimientos 8 Methodology Metodología 10 How to use the glossary Cómo usar el glosario 11 Categorization Categorización 12 Annual review process Proceso de revisión anual 13 Abbreviations Abreviaciones 13 Tips and tricks for PDF searches Consejos prácticos para la 14 búsqueda en documentos PDF* Sections Secciones Bilingual Glossary Glosario bilingüe English → Spanish Inglés → Español 15 Spanish → English Español → Inglés 121 Country of Origin Adjectives Gentilicios 229 Acronyms Siglas 231 References Referencias 235 Additional Resources Recursos adicionales 236 Introduction Introducción The HIV Prevention Bilingual Glossary (HPBG) El Glosario bilingüe de prevención del VIH is a collaborative effort to provide linguistic (GBPV) es un trabajo conjunto que tiene como support to individuals and organizations working objetivo dar apoyo lingüístico a las personas y with Spanish-speaking populations in the U.S. organizaciones que trabajan con poblaciones de habla hispana en los EE.UU. Partners for the development of this glossary include the Office of Minority Health Resource Para la elaboración de este glosario se contó Center (OMHRC) under the Office of Minority con el apoyo y colaboración de las siguientes Health (OMH) at the U.S.