Figurative Language ( Metaphors, Personification, Metonymy, Irony, Hyperbole Etc.) - Figure of Speech Dealing with the MEANING of Words– Cliché; Not Literal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AP English Literature and Composition: Study Guide

AP English Literature and Composition: Study Guide AP is a registered trademark of the College Board, which was not involved in the production of, and does not endorse, this product. Key Exam Details While there is some degree of latitude for how your specific exam will be arranged, every AP English Literature and Composition exam will include three sections: • Short Fiction (45–50% of the total) • Poetry (35–45% of the total) • Long Fiction or Drama (15–20% of the total) The AP examination will take 3 hours: 1 hour for the multiple-choice section and 2 hours for the free response section, divided into three 40-minute sections. There are 55 multiple choice questions, which will count for 45% of your grade. The Free Response writing component, which will count for 55% of your grade, will require you to write essays on poetry, prose fiction, and literary argument. The Free Response (or “Essay” component) will take 2 hours, divided into the three sections of 40 minutes per section. The course skills tested on your exam will require an assessment and explanation of the following: • The function of character: 15–20 % of the questions • The psychological condition of the narrator or speaker: 20–25% • The design of the plot or narrative structure: 15–20% • The employment of a distinctive language, as it affects imagery, symbols, and other linguistic signatures: 10–15% • And encompassing all of these skills, an ability to draw a comparison between works, authors and genres: 10–15 % The free response portion of the exam will test all these skills, while asking for a thesis statement supported by an argument that is substantiated by evidence and a logical arrangement of the salient points. -

Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions

http://lexikos.journals.ac.za; https://doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1604 Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions: A Slovene–English Case Study Marjeta Vrbinc, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Danko Šipka, School for International Letters and Cultures, Arizona State University, Tempe Campus, USA ([email protected]) and Alenka Vrbinc, School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Abstract: This article presents and discusses the findings of a study conducted with the users of Slovene and American monolingual dictionaries. The aim was to investigate how native speakers of Slovene and American English interpret select normative labels in monolingual dictionaries. The data were obtained by questionnaires developed to elicit monolingual dictionary users' attitudes toward normative labels and the effects the labels have on dictionary users. The results show that a higher level of prescriptivism in the Slovene linguistic culture is reflected in the Slovene respon- dents' perception of the labels (for example, a stronger effect of the normative labels, a higher approval for the claim about usefulness of the labels, a considerably lower general level of accep- tance for the standard language) when compared with the American respondents' perception, since the American linguistic culture tends to be more descriptive. However, users often seek answers to their linguistic questions in dictionaries, which means that they expect at least a certain degree of normativity. Therefore, a balance between descriptive and prescriptive approaches should be found, since both of them affect the users. Keywords: GENERAL MONOLINGUAL DICTIONARY, PRESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVITY, DESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVE LABELS, PRIMARY EXCLUSION LABELS, SECONDARY EXCLUSION LABELS, USE OF LABELS, USEFULNESS OF LABELS, (UN)LABELED ENTRIES Opsomming: Normatiewe etikette in twee leksikografiese tradisies: 'n Sloweens–Engelse gevallestudie. -

Supporting Children's Narrative Composition: the Development and Reflection of a Visual Approach for 7-8 Year-Olds

Supporting Children's Narrative Composition: the Development and Reflection of a Visual Approach for 7-8 Year-olds Teresa Noguera A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Sport and Education, Brunel University, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 1 Statement of Original Authorship The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree or diploma at any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made. Signed: Date: 2 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my mum‘s uncle, Jose Miguel Aldabaldetreku. He taught me the values that have shaped my whole life and showed me the importance of living with compassion, humility and generosity. This thesis is also dedicated with gratitude to ‗my‘ dear children (class 3B), and to all children, who continue to inspire vocational practitioners like myself to seek the intellectual and emotional potential within every human being, and who help us learn and become better practitioners and human beings. 3 Acknowledgements Of all the pages in this thesis, this has perhaps been the most difficult to compose. There are so many people I would like to thank, and for so many reasons, it seems hardly possible to express a small percentage of my gratitude on the space of a page. From the time I started on this journey I have been supported in a variety of ways: institutionally, financially, academically, and through the encouragement and friendship of some very special people. -

2018 Vermont Waste Characterization Study

2018 VERMONT WASTE CHARACTERIZATION FINAL REPORT | DECEMBER Prepared14, 2018 for: VERMONT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION, SOLID WASTE PROGRAM Prepared by: With support from: 2018 Vermont Waste Characterization FINAL REPORT | DECEMBER 14, 2018 REPORT TO THE: Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation, Solid Waste Program Prepared by: With support from: 2018 VERMONT WASTE CHARACTERIZATION | FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 Gate Surveys to Determine Generator Source ................................................................................................. 1 Residential Waste Composition ........................................................................................................................ 3 ICI Waste Composition...................................................................................................................................... 4 Aggregate Composition .................................................................................................................................... 4 Materials Recovery Rates ................................................................................................................................. 5 Construction and Demolition Waste ................................................................................................................ 5 Backyard Composting ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Place of Creative Writing in Composition Studies

H E S S E / T H E P L A C E O F C R EA T I V E W R I T I NG Douglas Hesse The Place of Creative Writing in Composition Studies For different reasons, composition studies and creative writing have resisted one another. Despite a historically thin discourse about creative writing within College Composition and Communication, the relationship now merits attention. The two fields’ common interest should link them in a richer, more coherent view of writing for each other, for students, and for policymakers. As digital tools and media expand the nature and circula- tion of texts, composition studies should pay more attention to craft and to composing texts not created in response to rhetorical situations or for scholars. In recent springs I’ve attended two professional conferences that view writ- ing through lenses so different it’s hard to perceive a common object at their focal points. The sessions at the Associated Writing Programs (AWP) consist overwhelmingly of talks on craft and technique and readings by authors, with occasional panels on teaching or on matters of administration, genre, and the status of creative writing in the academy or publishing. The sessions at the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) reverse this ratio, foregrounding teaching, curricular, and administrative concerns, featur- ing historical, interpretive, and empirical research, every spectral band from qualitative to quantitative. CCCC sponsors relatively few presentations on craft or technique, in the sense of telling session goers “how to write.” Readings by authors as performers, in the AWP sense, are scant to absent. -

Out of Style: Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2008 Out of Style: Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric Paul Butler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Butler, Paul, "Out of Style: Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric" (2008). All USU Press Publications. 162. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs/162 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 6679-0_OutOfStyle.ai79-0_OutOfStyle.ai 5/19/085/19/08 2:38:162:38:16 PMPM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K OUT OF STYLE OUT OF STYLE Reanimating Stylistic Study in Composition and Rhetoric PAUL BUTLER UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2008 Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 © 2008 Utah State University Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-87421-679-0 (paper) ISBN: 978-0-87421-680-6 (e-book) “Style in the Diaspora of Composition Studies” copyright 2007 from Rhetoric Review by Paul Butler. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Group, LLC., http:// www. informaworld.com. Manufactured in the United States of America. Cover design by Barbara Yale-Read. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Butler, Paul, Out of style : reanimating stylistic study in composition and rhetoric / Paul Butler. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

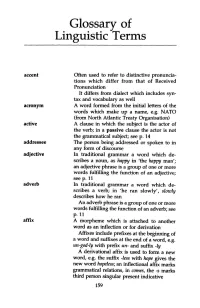

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

1 NAOJ English Composition Style Guide 1) the Purpose of This Guide

NAOJ English Composition Style Guide 1) The Purpose of this Guide As internationalization continues to increase, the amount of English language text produced about Japanese astronomy also continues to grow, along with the number or people who read these texts. This style guide contains suggestions to help writers convey their ideas in clear, concise English. By following these suggestions, the authors will help to maintain a consistent style across the various projects and centers of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ). Based on each situation and context as well as referring to the style guide, authors and editors can decide the clearest way to convey the information. This style guide is intended for use in general audience pieces released by NAOJ. General audience pieces include but are not limited to web pages, press releases, social media, pamphlets, fliers, NAOJ News, and the Annual Report. Academic papers published as part of the "Publications of NAOJ" have different guidelines which can be found at: <NAOJ guidelines for academic papers in English> http://library.nao.ac.jp/publications/nenji_e.html <NAOJ guidelines for academic papers in Japanese> http://library.nao.ac.jp/syuppan/rule.html http://library.nao.ac.jp/syuppan/format.html When working on a piece to be released by another organization, that organization’s style guide takes precedence. This style guide is not meant to be comprehensive. Many excellent books have been written about the fundamentals of English grammar. Instead, this guide is meant to serve as a quick reference guide for authors when they are unsure of the style. -

Introduction to Literature & Composition

INDEPENDENT LEAR NING S INC E 1975 COMMON CORE SUPPLEMENT Introduction to Literature & Composition Welcome to the Oak Meadow Common Core Supplement for Introduction to Literature and Composition. These supplemental assignments are intended for schools and individuals who use Oak Meadow curriculum and who need to be in compliance with Common Core Standards. Introduction Oak Meadow curricula provide a rigorous and progressive educational experience that meets intellectual and developmental needs of high school students. Our courses are designed with the goal of guiding learners to develop a body of knowledge that will allow them to be engaged citizens of the world. With knowledge gained through problem solving, critical thinking, hands-on projects, and experiential learning, we inspire students to connect disciplinary knowledge to their lives, the world they inhabit, and the world they would like to build. While our courses provide a compelling and complete learning experience, in a few areas our program may not be in complete alignment with recent Common Core standards. After a rigorous analysis of all our courses, we have developed a series of supplements to accompany our materials for schools who utilize our curricula. These additions make our materials Common Core compliant. These Common Core additions are either stand-alone new lessons or add-ons to existing lessons. Where they fall in regard to the larger curriculum is clearly noted on each supplement lesson. Included in this supplement are the following 1. New reading, writing, speaking and critical analysis assignments designed to be used with the existing Oak Meadow curriculum readings and materials 2. Language usage lessons and explanations Oak Meadow’s Write It Right: A Handbook for Student Writers and A Pocket Style Manual by Hacker and Sommers are meant to be used in conjunction with with this supplement and the entire Oak Meadow curriculum. -

Introduction to the Paratext Author(S): Gérard Genette and Marie Maclean Source: New Literary History, Vol

Introduction to the Paratext Author(s): Gérard Genette and Marie Maclean Source: New Literary History, Vol. 22, No. 2, Probings: Art, Criticism, Genre (Spring, 1991), pp. 261-272 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/469037 Accessed: 11-01-2019 17:12 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to New Literary History This content downloaded from 128.227.202.135 on Fri, 11 Jan 2019 17:12:58 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction to the Paratext* Gerard Genette HE LITERARY WORK consists, exhaustively or essentially, of a text, that is to say (a very minimal definition) in a more or less lengthy sequence of verbal utterances more or less con- taining meaning. But this text rarely appears in its naked state, without the reinforcement and accompaniment of a certain number of productions, themselves verbal or not, like an author's name, a title, a preface, illustrations. One does not always know if one should consider that they belong to the text or not, but in any case they surround it and prolong it, precisely in order to present it, in the usual sense of this verb, but also in its strongest meaning: to make it present, to assure its presence in the world, its "reception" and its consumption, in the form, nowadays at least, of a book. -

Literature Review Sample Outline*

Writing Literature Reviews Francesca Gacho, [email protected] Graduate Writing Coach, School of Communication Literature Review Sample Outline* *This is an outline for a paper that already has an introduction where 1) the research field and topic has been described, 2) a review of relevant literature has been given to provide context, and 3) a research question or thesis statement has already been identified. This sample has been modified to address CMGT 540 requirements. Introduction (already written) I. CARS Model followed for the structure of the Introduction II. Example Research Question: What features of composition and rhetoric characterize graduate student writing in interdisciplinary contexts? Literature Review III. First Bucket or Theme 1: Student Writing a. Overview of the characteristics of the theme (commonalities, differences, nuances) b. Subtheme 1 (narrow, but grouped findings related to the theme): Undergraduate Writing i. Study 1 (Research Question(s), Methods/Participants, Related Findings): “In a qualitative study examining Latino high school students, Campos (2016) found that the participants ….” ii. Study 2 (Research Question(s), Methods/Participants, Related Findings): “In a similar study with African-American high school students, Sung (2015) identified three key factors…Sung surveyed across three different high schools, which may partially explain differences in responses.” iii. Study 3 (Research Question(s), Methods/Participants, Related Findings) iv. Do these studies share commonalities? How do these studies differ? Discuss. c. Subtheme 2: Graduate Writing i. Study 1 (Research Question(s), Methods/Participants, Related Findings) ii. Study 2 (Research Question(s), Methods/Participants, Related Findings) iii. Study 3 (Research Question(s), Methods/Participants, Related Findings) iv. -

Anecdotes and Mimesis in Visual Music

Diego Garro The poetry of things: anecdotes and mimesis in Visual Music ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The poetry of things: anecdotes and mimesis in Visual Music DIEGO GARRO Keele University, School of Humanities – Music and Music Technology, The Clockhouse, Keele ST5 5BG, UK E-mail: [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION Ten years into the third millennium, Visual Music is a discipline firmly rooted in the vast array of digital arts, more diversified than ever in myriads of creative streams, diverging, intersecting, existing in parallel artistic universes, often contiguous, unaware of each other, perhaps, yet under the common denominator of more and more sophisticated media technology. Computers and dedicated software applications, allow us to create, by means of sound and animation synthesis, audio-visuals entirely in the digital domain. In line with the spectro-morphological tradition of much of the electroacoustic repertoire, Visual Music works produced by artists of sonic arts provenance, are predominantly abstract, especially in terms of the imagery they resort to. Nonetheless, despite the ensuing non-representational idiom that typifies many Visual Music works, composers enjoyed the riveting opportunity to employ material, both audio and video, which possess clear mimetic potential (Emmerson 1986, p.17), intended here as the ability to imitate nature or refer to it, more or less faithfully and literally. Composers working in the electronic media still enjoy the process of ‘capturing’ events from the real world and use them, with various strategies, as building blocks for time-based compositions. Therefore, before making their way into the darkness of computer-based studios, they still use microphones and video-cameras to harvest sounds, images, ideas, fragments, anecdotes to be thrown into the prolific cauldron of a compositional kitchen-laboratory-studio.