Dmytro Zaiets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project Environmental and Social Due

Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project Environmental and Social Due Diligence Non-Technical Summary Date: 07 July 2017 Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project ESDD: Non-Technical Summary July 2017 Supported by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Funding provided by the Japan-EBRD Cooperation Fund Page2 2 of 19 Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project ESDD: Non-Technical Summary July 2017 Glossary Definitions The Bank The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development The Company The Kharkiv Metro Company (or KMC) The Green Line Oleksiivska Line of Kharkiv Metro System The Project Expansion of the metro system expansion: i) extension of the existing 9-station Metro Green Line (“Oleksiyivska”) by 3.47 km and construction of two new stations “Derzhavynska” and “Odeska”; ii) construction of a metro depot “Oleksiyivske” and connection to Metro Green Line; iii) acquisition of rolling stock. The Project Site Land plots where the extension of the line, auxiliary premises and depot will be constructed Abbreviations ACM Asbestos-containing materials EBRD The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EHS Environment, Health and Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment (a volume of Design Documents) ESAP Environmental and Social Action Plan ESDD Environmental and Social Due Diligence ESMS Environmental and Social Management System ESP Environmental and Social Policy of EBRD (2014) EU European Union GHG Greenhouse Gases (restricted to GHG under the Kyoto Protocol: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, sulphur hexafluoride and two groups of gases -

Environmental and Social Due Diligence Environmental and Social Analysis Report

Contract: C32715/JPN-2015-06-03 Client: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development Project: Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project Services: Feasibility Study Environmental and Social Due Diligence Environmental and Social Analysis Report Date: 07 July 2016 Revision 01: 02 October 2016 Revision 02: 18 August 2017 BERNARD Ingenieure ZT GmbH Bahnhofstrasse 19 6060 Hall in Tirol Austria In association with: Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project BERNARD – SGS – ISP – AXIS ESDD: Environmental and Social Analysis Report July 2017 Supported by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Funding provided by the Japan-EBRD Cooperation Fund Page 2 of 56 Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project BERNARD – SGS – ISP – AXIS ESDD: Environmental and Social Analysis Report July 2017 Register of Submissions Project no.: 7729 Prepared by: BERNARD Ingenieure ZT GmbH Bahnhofstrasse 19, 6060 Hall in Tirol, Austria Phone: +43 5223 5840 0 Email: [email protected] Prepared for: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development One Exchange Square, London EC2A 2JN, United Kingdom Phone: +7 495 787 1122 Email: [email protected] Document name: Kharkiv-Metro_ESDD_9-2_Analysis-Report_2017-06-30.docx Rev No. Date Description 00 07.07.2016 Submission of Environmental and Social Analysis Report 01 02.10.2016 Revision of report in accordance with EBRD’s comments 02 18.08.2017 Update of greenhouse gas calculations and other minor amendments Prepared by: Verified by: Approved by: Oleksandr Kislitsyn Reinoud van der Auweraert Martin Kraft-Fish Report prepared by Tebodin Ukraine CFI Page3 3 of 56 Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project BERNARD – SGS – ISP – AXIS ESDD: Environmental and Social Analysis Report July 2017 Executive Summary A Consultancy Contract dated 9 December 2015 for the Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project – Feasibility Study has been signed by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and BERNARD Ingenieure ZT GmbH, who contracted Tebodin Ukraine CFI for the Environmental and Social Due Diligence (ESDD). -

Poland Ukraine Fanguide Euro2012 CONTENTS Fanguide 2012 - Contents

Poland Ukraine Fanguide euro2012 CONTENTS Fanguide 2012 - Contents Contents 03 04 Foreword FSE/UEFA Welcome to Poland/Ukraine 06 Poland A-Z 08 Group A - Warsaw 14 Group A - Wrocław 16 Group A - Competing Countries 18 Group C - Gdańsk 22 Group C - Poznań 24 Group C - Competing Countries 26 Contents 30 Safety and Security 03 Match Schedule 32 34 Ukraine A-Z 40 Group B - Lviv 42 Group B - Kharkiv 44 Group B - Competing Countries 48 Group D - Kiev 50 Group D - Donetsk 52 Group D - Competing Countries Information for disabled fans 56 58 Words and Phrases - Ukraine Words and Phrases - Poland 60 62 Respect fansembassy.org // 2012fanguide.org // facebook.com/FansEmbassies // Twitter @FansEmbassies Foreword from FSE FSE Foreword from UEFA UEFA More than just a tourist guide… The thinking behind what we do is simple: supporters are the heart of football. If Welcome to Poland and Ukraine; These initiatives offer knowledge and insights Dear football supporters from all over you view fans coming to a tournament welcome to UEFA EURO 2012 from those who know best – your fellow Europe, Welcome to Euro 2012, as guests to be treated with respect and supporters. A key factor of the concept is Foreword from FSE and welcome to Poland and Ukraine! not as a security risk to be handled by “The supporters are the lifeblood of the production of fan guides with practical Foreword from UEFA police forces, they will behave accordingly. football“– that belief has formed UEFA’s information in different languages but, 04 What you are holding in your hands right They will enjoy themselves, party attitude towards football fans throughout most importantly, written in our common 05 now is the Football Supporters Europe (FSE) together and create a great atmosphere. -

Department of Psychiatry, Narcology, Neurology and Medical Psychology

V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry, Narcology, Neurology and Medical Psychology GENERAL INFORMATION Today the Department of Psychiatry, Narcology, Neurology and Medical Psychology is one of the leading in Ukraine. Highly qualified specialists represent the researching and teaching staff. The department holds a high-level educational and methodical work with innovative approaches and presents the results of modern scientific research. DEPARTMENT’S HISTORY The history of the Department of Psychiatry, Narcology, Neurology and Medical Psychology at the School of Medicine of the V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University actually begins with the foundation of the University. Recalling the history of psychiatry should be stressed that for the first time in Russia, professor of the Surgery Department of the Kharkiv Imperial University, P. A. Butkovskiy introduced the lectures of independent course of psychiatry since 1834. In the same year, the first Russian textbook of psychiatry "Mental Illness" was published. The teaching of Psychiatry at the Kharkiv Imperial University was conducted by the world famous professors: F. K. Albrecht, K. A. Demonsi, V. G. Lashkevich, J. S. Kremyanskiy. The first independent Department of Psychiatry and Neurology in Ukraine was established in 1877 and it was based on an independent course of psychiatry in the Kharkiv Imperial University, headed by professor P. I. Kovalevskiy. He trained many talented psychiatrists with a worldwide reputation: M. P. Popov, N. I. Mukhin, K. I. Platonov and others. After P. I. Kovalevsky the department was headed by N. I. Mukhin, and from 1894 to the October Revolution by J. A. Anfimov. -

Georesources and Environment Geological Hazards During

International Journal of IJGE 2018 4(4): 187-200 Georesources and Environment http://ijge.camdemia.ca, [email protected] Available at http://ojs.library.dal.ca/ijge Geotechnical Engineering and Construction Geological Hazards During Construction and Operation of Shallow Subway Stations and Tunnels by the Example of the Kharkiv Metro (1968–2018) Viacheslav Iegupov*, Genadiy Strizhelchik, Anna Kupreychyk, Artem Ubiyvovk Department of Geotechnics and Underground Structures, Kharkiv National University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 40 Sumska Street, Kharkiv, Ukraine Abstract: Scientific, technical and practical problems have been considered in relation to geological hazards during construction and operation of metro objects such as shallow subway stations and tunnels. Analysis of five decades of the experience of construction and subsequent operation of the Kharkiv metro in rough engineering and geological conditions by construction of tunnels at shallow depths under the existing urban development allowed detecting and systematizing a set of the most essential adverse conditions, processes and phenomena. The main geological hazards are related to the expansion of quicksands, possibility of “flotation” of the underground structures, barrage effect, subsidence of the soil body by long-term dewatering, undermining of the built-in territories and difficulties by tunneling in technogenic fill-up grounds when crossing ravines and gullies. Most problems occur in the territories with a high groundwater level: geological risks in these areas increase, and serious incidents occur by sudden adverse changes of hydrodynamic conditions. Zones of high, medium and low geological hazards have been identified. Geological hazards have been defined at the section planned for extension of the metro line, for which calculations of the affluent value were made based on the barrage effect of tunnels on the groundwater flow. -

Mapping Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure in the Western

INTERNAL REPORT | APRIL 2020 For more information Mapping Sustainable Municipal Emily Gray Research Coordinator Infrastructure in the Western Balkans CEE Bankwatch Network [email protected] and Eastern Neighbourhood Belgrade Green Boulevard, October 2019 Photo: Emily Gray CEE Bankwatch Network’s mission is to prevent environmentally and socially harmful impacts of international development finance, and to promote alternative solutions and public participation. Learn more: bankwatch.org CEE Bankwatch Network 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following individuals were instrumental in the design and development of the study, data collection, and writing: Fidanka Bacheva-McGrath, Maria-Laura Camarut, Megan Feng, Pippa Gallop, Petr Hlobil, David Hoffman, Manana Kochladze, Nina Lesikhina, Olexi Pasyuk, Davor Pehchevski, Anna Roggenbruck and Erica Witt. Special thanks to all participants who generously gave their time to be interviewed for this study. This study is supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). SIDA cannot ensure that they completely endorse the content of what is communicated in this report. CEE Bankwatch Network 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The latest research on climate change indicates that changes to urban life have the potential to make a substantial contribution to reducing emissions, consumption, and land use. International financial institutions have addressed this by providing much- needed funding for the implementation, upgrade, and expansion of infrastructure in municipalities. However, the real impact of the investments on sustainability, especially in terms of the environment and human rights, is still not clear. This study investigates the impact that such investments have had on local communities in the Western Balkans and Eastern Neighbourhood by looking at the perceptions of CSOs in these regions. -

Of the Public Purchasing Announcernº42 (64) October 18, 2011

Bulletin ISSN: 2078–5178 of the public purchasing AnnouncerNº42 (64) October 18, 2011 Announcements of conducting procurement procedures � � � � � � � � � 2 Announcements of procurement procedures results � � � � � � � � � � � � 48 Urgently for publication � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 88 Bulletin No�42 (64) October 18, 2011 Annoucements of conducting 18417 Subsidiary Company “Ukrtransgaz”, Affiliate procurement procedures of Main Gas Pipelines Department “Kyivtransgaz” 44 Komarova Ave., 03065 Kyiv Azhhireieva Olena Vadymivna 18415 Utility Enterprise “Ivano– tel.: (044) 239–78–15; Frankivskvodoekotekhprom” tel./fax: (044) 239–78–44; 2 Botanichna St., 76011 Ivano–Frankivsk e–mail: [email protected] Holynskyi Oleh Mykhailovych Procurement subject: code 33.20.9 – services in assemblage, maintenance tel.: (0342) 75–92–61; and repair of measurement and test equipment (repair of gas sampling tel./fax: (0342) 77–51–56; sites according to DSTU ISO 10715 in Lubny and Dykanka Linear e–mail: [email protected] Production Administration of Main Gas Pipelines) Procurement subject: code 25.21.2 – plastic pipes, tubes, pipelines Supply/execution: Lubny Linear Production Administration of Main Gas Pipelines and fittings, 7 dnms. (22/2 Volodymyrskyi Maidan, 37500 Lubny, Poltava Oblast), Dykanka Linear Supply/execution: at the customer’s address, December 2011 – September 2012 Production Administration of Main Gas Pipelines (65 Kuibysheva St., 38500 Procurement procedure: open tender Dykanka Urban Settlement, Poltava -

Reference List 1994-2020 Reference-List 2020 2

1 1 pluton.ua REFERENCE LIST 1994-2020 REFERENCE-LIST 2020 2 CONTENTS 3 METRO 23 CITY ELECTRIC TRANSPORT 57 RAILWAYS 69 INDUSTRIAL, IRON AND STEEL, MACHINE-BUILDING, RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ENTERPRISES 79 POWER INDUSTRY 2 3 METRO UKRAINE RUSSIAN FEDERATION KHARKIV METRO 4 YEKATERINBURG METRO 16 KYIV METRO 6 MOSCOW METRO 18 KAZAN METRO 18 REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN NIZHNY NOVGOROD METRO 19 ALMATY METRO 8 ST. PETERSBURG METRO 19 REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN BAKU METRO 10 TASHKENT METRO 20 REPUBLIC OF BELARUS ROMANIA MINSK METRO 14 BUCHAREST METRO 20 REPUBLIC OF KOREA BUSAN СITY METRO 21 DAWONSYS COMPANY 21 REPUBLIC OF TURKEY IZMIR METRO 21 REFERENCE-LIST 2020 4 KHARKIV METRO KHARKIV, UKRAINE Turn-key projects: 2003- 3 traction substations of 23 Serpnia, Botanichnyi Sad, Oleksiivska NEX Switchgear 6 kV 1 set 2009 metro stations. NEX Switchgear 10 kV 1 set Supply of equipment, installation works, commissioning, startup. DC Switchgear 825 V 26 units 2016 Traction substation of Peremoha metro station. Transformer 10 units Supply of equipment, installation supervision, commissioning, Rectifier 12 units startup. Telecontrol equipment 1 set 2017 Tunnel equipment for the dead end of Istorychnyi Muzei metro station and low voltage equipment for Kharkiv Metro AC Switchgear 0.23...0.4 kV 5 sets Administration building power supply. DC Distribution Board 2 sets Supply of equipment, installation, commissioning. Communications Based Train Control Switchgear 2 sets Equipment for tunnels and depots: Line Disconnector Cabinet 15 units Implemented -

Screen Template

Ukraine: your new Shared Service Centre v destination Looking for a new location? We can help 2017 edition Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 Executive summary 5 2. Why Ukraine is attractive to investors 6 3. Prime locations for a SSC 15 — Kyiv 16 — Lviv 22 — Ivano-Frankivsk 28 — Dnipro 34 — Odesa 40 — Kharkiv 46 4. Overview of legal matters for doing business in Ukraine 52 About KPMG and our services 54 © 2017 JSC KPMG Audit, a company incorporated under the Laws of Ukraine, a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative ("KPMG International"), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. 2 1. Introduction 1.1 How much does location matter when operating a successful shared services centre (SSC)? The main idea of a SSC is to take the operations of individual units Ukraine: your new in a business and centralise them. The same services are then provided at lower cost but at the same or better quality. destination for BPO/SSC This improves productivity as centralisation and standardisation creates additional benefits that increase competitiveness. The pace of globalisation and the growing momentum behind technological development is pressuring companies to set up SSCs capable of providing 24/7 global service coverage from one place. As such, the SSC model is attracting more attention. Key to all of this is cost management and the availability of talent. Without these factors in place, a company will not consider setting up a SSC in a particular location. The right location is of utmost importance for the success of any SSC. -

List of Longest Tunnels in the World

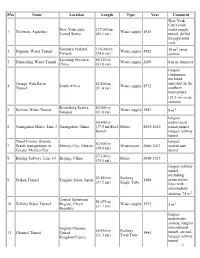

SNo Name Location Length Type Year Comment New York City's main New York state, 137,000 m water supply 1 Delaware Aqueduct Water supply 1945 United States (85.1 mi) tunnel, drilled through solid rock. Southern Finland, 120,000 m 2 2 Päijänne Water Tunnel Water supply 1982 16 m cross Finland (74.6 mi) section Liaoning Province, 85,320 m 3 Dahuofang Water Tunnel Water supply 2009 8 m in diameter China (53.0 mi) longest continuous enclosed Orange–Fish River 82,800 m aqueduct in the 4 South Africa Water supply 1972 Tunnel (51.4 mi) southern hemisphere (22.5 m2 cross section) Kronoberg/Scania, 82,000 m 5 Bolmen Water Tunnel Water supply 1987 2 Sweden (51.0 mi) 8 m longest 60,400 m metro/rapid 6 Guangzhou Metro: Line 3 Guangzhou, China (37.5 mi)Excl. Metro 2005-2010 transit tunnel branch longest railway tunnel Tunel Emisor Oriente: longest 62,500 m 7 Water management in Mexico City, Mexico Waterwaste 2006-2012 waterwaste (38.8 mi) Greater Mexico City tunnel 57,100 m 8 Beijing Subway: Line 10 Beijing, China Metro 2008-2012 (35.5 mi) longest railway tunnel excluding 53,850 m Railway 9 Seikan Tunnel Tsugaru Strait, Japan 1988 urban metro (33.5 mi) Single Tube lines with intermediate stations, 74 m2 Central Bohemian 51,075 m 10 Želivka Water Tunnel Region, Czech Water supply 1972 2 (31.7 mi) 5 m Republic longest underwater section, longest English Channel, international 50,450 m Railway 11 Channel Tunnel United 1994 tunnel, second- (31.3 mi) Twin Tube Kingdom/France longest railway tunnel 2 (2×45 m + 1×18 m2) Armenia (at the time of 48,300 m 12 -

The EBRD and EIB's Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure Investments

BRIEFING | JUNE 2020 For more information The EBRD and EIB’s Sustainable Emily Gray Research Coordinator Municipal Infrastructure Investments CEE Bankwatch Network [email protected] in the Western Balkans and Eastern Neighbourhood In the face of ambitious international goals to promote sustainable development and to stem climate change and its negative effects, a transformation of urban life can make a significant contribution to reducing emissions, consumption, and land use. International financial institutions (IFIs) such as the EBRD and EIB have addressed global calls for sustainable urban transformation by providing much-needed funding for the implementation, upgrade, and expansion of infrastructure in municipalities. However, in order for this infrastructure to be truly sustainable, it must meet the needs of the people who will use it – meaning citizens must be involved in its planning – and it must meet the highest criteria in terms of its impact on the environment and human well-being. From October to December 2019, Bankwatch conducted a study to understand how civil society organisations (CSOs) in the Western Balkans and Eastern Neighbourhood perceive IFI-funded infrastructure projects and strategic plans in their municipalities.1 For more on our methodology, see Annex 1: Methodology. How Do CSOs View the EBRD and EIB’s Investments in Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure? We surveyed 16 CSO representatives from the two regions of focus about their experiences with EBRD- and EIB-funded projects in their municipalities and