Mapping Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure in the Western

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dmytro Zaiets

Contemporary public art in the city space of Kharkiv1 Dmytro Zaiets, Department of Theoretical Sociology, Kharkiv National University; and Center for Social Studies, Institute of Sociology and Philosophy of the Polish Academy of Sciences Reflecting on the space of the city and its visual content with different kinds of art, I make no claim to originality. Art has always served an aesthetic, memorial and ideological function in the politics of urban planning, from сave drawings, through the medieval cathedral to the posters of Soviet socialist realist art. But the second half of the 20th century was distinguished, among other innovations, by the inclusion of art in the process of structuration of the urban environment, the set of visual patterns with the intent to “switch” the mode of “seeing” the city through a new formula for urban art, namely public art. This specific approach to contemporary art arose as both a consequence and a “mediator” of civil engagement in the public sphere of Western European and American cities in the 1960s. As such, public art tries through creative means to change the visual models through which the city is perceived. Therefore, public art is not only art, but also incorporates specific socio-cultural practices including the ontology and methods of visual anthropology and ethnography, semiotics, media theory, and other approaches that are not typically applied to the field of art criticism. Works of public art are reminiscent of a social experiment that simulates the sensation of displacement and confusion by creating innuendo and then challenges conventional codes and stereotypes, familiar relationships and social attitudes. -

Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project Environmental and Social Due

Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project Environmental and Social Due Diligence Non-Technical Summary Date: 07 July 2017 Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project ESDD: Non-Technical Summary July 2017 Supported by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Funding provided by the Japan-EBRD Cooperation Fund Page2 2 of 19 Kharkiv Metro Expansion Project ESDD: Non-Technical Summary July 2017 Glossary Definitions The Bank The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development The Company The Kharkiv Metro Company (or KMC) The Green Line Oleksiivska Line of Kharkiv Metro System The Project Expansion of the metro system expansion: i) extension of the existing 9-station Metro Green Line (“Oleksiyivska”) by 3.47 km and construction of two new stations “Derzhavynska” and “Odeska”; ii) construction of a metro depot “Oleksiyivske” and connection to Metro Green Line; iii) acquisition of rolling stock. The Project Site Land plots where the extension of the line, auxiliary premises and depot will be constructed Abbreviations ACM Asbestos-containing materials EBRD The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EHS Environment, Health and Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment (a volume of Design Documents) ESAP Environmental and Social Action Plan ESDD Environmental and Social Due Diligence ESMS Environmental and Social Management System ESP Environmental and Social Policy of EBRD (2014) EU European Union GHG Greenhouse Gases (restricted to GHG under the Kyoto Protocol: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, sulphur hexafluoride and two groups of gases -

Georesources and Environment Geological Hazards During

International Journal of IJGE 2018 4(4): 187-200 Georesources and Environment http://ijge.camdemia.ca, [email protected] Available at http://ojs.library.dal.ca/ijge Geotechnical Engineering and Construction Geological Hazards During Construction and Operation of Shallow Subway Stations and Tunnels by the Example of the Kharkiv Metro (1968–2018) Viacheslav Iegupov*, Genadiy Strizhelchik, Anna Kupreychyk, Artem Ubiyvovk Department of Geotechnics and Underground Structures, Kharkiv National University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, 40 Sumska Street, Kharkiv, Ukraine Abstract: Scientific, technical and practical problems have been considered in relation to geological hazards during construction and operation of metro objects such as shallow subway stations and tunnels. Analysis of five decades of the experience of construction and subsequent operation of the Kharkiv metro in rough engineering and geological conditions by construction of tunnels at shallow depths under the existing urban development allowed detecting and systematizing a set of the most essential adverse conditions, processes and phenomena. The main geological hazards are related to the expansion of quicksands, possibility of “flotation” of the underground structures, barrage effect, subsidence of the soil body by long-term dewatering, undermining of the built-in territories and difficulties by tunneling in technogenic fill-up grounds when crossing ravines and gullies. Most problems occur in the territories with a high groundwater level: geological risks in these areas increase, and serious incidents occur by sudden adverse changes of hydrodynamic conditions. Zones of high, medium and low geological hazards have been identified. Geological hazards have been defined at the section planned for extension of the metro line, for which calculations of the affluent value were made based on the barrage effect of tunnels on the groundwater flow. -

Reference List 1994-2020 Reference-List 2020 2

1 1 pluton.ua REFERENCE LIST 1994-2020 REFERENCE-LIST 2020 2 CONTENTS 3 METRO 23 CITY ELECTRIC TRANSPORT 57 RAILWAYS 69 INDUSTRIAL, IRON AND STEEL, MACHINE-BUILDING, RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ENTERPRISES 79 POWER INDUSTRY 2 3 METRO UKRAINE RUSSIAN FEDERATION KHARKIV METRO 4 YEKATERINBURG METRO 16 KYIV METRO 6 MOSCOW METRO 18 KAZAN METRO 18 REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN NIZHNY NOVGOROD METRO 19 ALMATY METRO 8 ST. PETERSBURG METRO 19 REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN BAKU METRO 10 TASHKENT METRO 20 REPUBLIC OF BELARUS ROMANIA MINSK METRO 14 BUCHAREST METRO 20 REPUBLIC OF KOREA BUSAN СITY METRO 21 DAWONSYS COMPANY 21 REPUBLIC OF TURKEY IZMIR METRO 21 REFERENCE-LIST 2020 4 KHARKIV METRO KHARKIV, UKRAINE Turn-key projects: 2003- 3 traction substations of 23 Serpnia, Botanichnyi Sad, Oleksiivska NEX Switchgear 6 kV 1 set 2009 metro stations. NEX Switchgear 10 kV 1 set Supply of equipment, installation works, commissioning, startup. DC Switchgear 825 V 26 units 2016 Traction substation of Peremoha metro station. Transformer 10 units Supply of equipment, installation supervision, commissioning, Rectifier 12 units startup. Telecontrol equipment 1 set 2017 Tunnel equipment for the dead end of Istorychnyi Muzei metro station and low voltage equipment for Kharkiv Metro AC Switchgear 0.23...0.4 kV 5 sets Administration building power supply. DC Distribution Board 2 sets Supply of equipment, installation, commissioning. Communications Based Train Control Switchgear 2 sets Equipment for tunnels and depots: Line Disconnector Cabinet 15 units Implemented -

Screen Template

Ukraine: your new Shared Service Centre v destination Looking for a new location? We can help 2017 edition Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 Executive summary 5 2. Why Ukraine is attractive to investors 6 3. Prime locations for a SSC 15 — Kyiv 16 — Lviv 22 — Ivano-Frankivsk 28 — Dnipro 34 — Odesa 40 — Kharkiv 46 4. Overview of legal matters for doing business in Ukraine 52 About KPMG and our services 54 © 2017 JSC KPMG Audit, a company incorporated under the Laws of Ukraine, a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative ("KPMG International"), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. 2 1. Introduction 1.1 How much does location matter when operating a successful shared services centre (SSC)? The main idea of a SSC is to take the operations of individual units Ukraine: your new in a business and centralise them. The same services are then provided at lower cost but at the same or better quality. destination for BPO/SSC This improves productivity as centralisation and standardisation creates additional benefits that increase competitiveness. The pace of globalisation and the growing momentum behind technological development is pressuring companies to set up SSCs capable of providing 24/7 global service coverage from one place. As such, the SSC model is attracting more attention. Key to all of this is cost management and the availability of talent. Without these factors in place, a company will not consider setting up a SSC in a particular location. The right location is of utmost importance for the success of any SSC. -

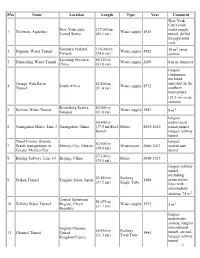

List of Longest Tunnels in the World

SNo Name Location Length Type Year Comment New York City's main New York state, 137,000 m water supply 1 Delaware Aqueduct Water supply 1945 United States (85.1 mi) tunnel, drilled through solid rock. Southern Finland, 120,000 m 2 2 Päijänne Water Tunnel Water supply 1982 16 m cross Finland (74.6 mi) section Liaoning Province, 85,320 m 3 Dahuofang Water Tunnel Water supply 2009 8 m in diameter China (53.0 mi) longest continuous enclosed Orange–Fish River 82,800 m aqueduct in the 4 South Africa Water supply 1972 Tunnel (51.4 mi) southern hemisphere (22.5 m2 cross section) Kronoberg/Scania, 82,000 m 5 Bolmen Water Tunnel Water supply 1987 2 Sweden (51.0 mi) 8 m longest 60,400 m metro/rapid 6 Guangzhou Metro: Line 3 Guangzhou, China (37.5 mi)Excl. Metro 2005-2010 transit tunnel branch longest railway tunnel Tunel Emisor Oriente: longest 62,500 m 7 Water management in Mexico City, Mexico Waterwaste 2006-2012 waterwaste (38.8 mi) Greater Mexico City tunnel 57,100 m 8 Beijing Subway: Line 10 Beijing, China Metro 2008-2012 (35.5 mi) longest railway tunnel excluding 53,850 m Railway 9 Seikan Tunnel Tsugaru Strait, Japan 1988 urban metro (33.5 mi) Single Tube lines with intermediate stations, 74 m2 Central Bohemian 51,075 m 10 Želivka Water Tunnel Region, Czech Water supply 1972 2 (31.7 mi) 5 m Republic longest underwater section, longest English Channel, international 50,450 m Railway 11 Channel Tunnel United 1994 tunnel, second- (31.3 mi) Twin Tube Kingdom/France longest railway tunnel 2 (2×45 m + 1×18 m2) Armenia (at the time of 48,300 m 12 -

The EBRD and EIB's Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure Investments

BRIEFING | JUNE 2020 For more information The EBRD and EIB’s Sustainable Emily Gray Research Coordinator Municipal Infrastructure Investments CEE Bankwatch Network [email protected] in the Western Balkans and Eastern Neighbourhood In the face of ambitious international goals to promote sustainable development and to stem climate change and its negative effects, a transformation of urban life can make a significant contribution to reducing emissions, consumption, and land use. International financial institutions (IFIs) such as the EBRD and EIB have addressed global calls for sustainable urban transformation by providing much-needed funding for the implementation, upgrade, and expansion of infrastructure in municipalities. However, in order for this infrastructure to be truly sustainable, it must meet the needs of the people who will use it – meaning citizens must be involved in its planning – and it must meet the highest criteria in terms of its impact on the environment and human well-being. From October to December 2019, Bankwatch conducted a study to understand how civil society organisations (CSOs) in the Western Balkans and Eastern Neighbourhood perceive IFI-funded infrastructure projects and strategic plans in their municipalities.1 For more on our methodology, see Annex 1: Methodology. How Do CSOs View the EBRD and EIB’s Investments in Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure? We surveyed 16 CSO representatives from the two regions of focus about their experiences with EBRD- and EIB-funded projects in their municipalities and -

Meeting Report

TMDWTS/2021 Meeting report Technical meeting on the future of decent and sustainable work in urban transport services (Geneva, 30 August–3 September 2021) Sectoral Policies Department Geneva, 2021 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2021 First edition 2021 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Meeting report, Technical meeting on the future of decent and sustainable work in urban transport services (Geneva, 30 August–3 September 2021), International Labour Office, Sectoral Policies Department, Geneva, ILO, 2021. ISBN 978-92-2-034292-3 (print) ISBN 978-92-2-034293-0 (Web pdf) Also available in French: Rapport de réunion, Réunion technique sur l’avenir du travail décent et durable dans les services de transport urbain (Genève, 30 août–3 septembre 2021), ISBN 978-92-2-034304-3 (print), ISBN 978-92-2-034305-0 (Web pdf), Geneva, 2021, and in Spanish: Informe de la reunión, Reunión técnica sobre el futuro del trabajo decente y sostenible en los servicios de transporte urbano (Ginebra, 30 de agosto – 3 de septiembre de 2021), ISBN 978-92-2-034302-9 (print), ISBN 978-92-2-034303-6 (Web pdf), Genève, 2021. -

URBAN RAIL CAPABILITIES London Tramlink: Special 20-Page Review

THE INTERNATIONAL LIGHT RAIL MAGAZINE HEADLINES l Toronto council takes key LRT vote l Bombardier close to 775-car BART order l Alstom demonstrates Citadis in Moscow SIEMENS BOLSTERS GLOBAL URBAN RAIL CAPABILITIES London Tramlink: Special 20-page review The end for paper? Driver safety: Easier for riders, Latest research better for operators: on managing 75 Smart ticketing driver risk for systems explained safer systems MAY 2012 No. 893 1937–2012 WWW. LRTA . ORG l WWW. TRAMNEWS . NET £3.80 TAUT_April12_Cover.indd 1 3/4/12 12:12:59 XX_TAUT1205_UITPAD.indd 1 2/4/12 09:58:22 Contents The official journal of the Light Rail Transit Association 168 News 168 MAY 2012 Vol. 75 No. 893 Toronto light rail supporters win key vote; Siemens www.tramnews.net announces global expansion ambitions; Alstom EDITORIAL demonstrates its Citadis tram in Moscow; Bombardier Editor: Simon Johnston preferred bidder for USD3.4bn, 775-car BART order. Tel: +44 (0)1832 281131 E-mail: [email protected] Eaglethorpe Barns, Warmington, Peterborough PE8 6TJ, UK. 174 Smart ticketing technologies Associate Editor: Tony Streeter John Austin examines the strategies operators can and are E-mail: [email protected] employing to drive ridership – and looks to the future. Worldwide Editor: Michael Taplin 174 Flat 1, 10 Hope Road, Shanklin, Isle of Wight PO37 6EA, UK. 179 Creating safer journeys E-mail: [email protected] Dr Lisa Dorn explains how detailed research is shaping News Editor: John Symons tram driver employment and training regimes. 17 Whitmore Avenue, Werrington, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffs ST9 0LW, UK. Systems Factfile: Valencia E-mail: [email protected] 183 Contributor: Neil Pulling Introducing modern trams to Spain was just one part of a project to drastically restructure public transport in its Design: Debbie Nolan third-largest city. -

EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BANK CA/507/17 18 October 2017 PV/17

EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BANK CA/507/17 18 October 2017 PV/17/08 B O A R D O F D I R E C T O R S Minutes of the meeting held in Sofia on Monday and Tuesday, 18 and 19 September 2017 Parts of this document that, at the time of the meeting, fall under the exceptions for disclosure defined by the EIB Group Transparency Policy*, notably under articles 5.5 (protection of commercial interests) and 5.6 (protection of the Bank’s internal decision- making process), have been replaced by the symbol […]. 2 Those attending Chairman: Mr W. HOYER Vice-Chairs: Messrs D. SCANNAPIECO P. van BALLEKOM J. TAYLOR R. ESCOLANO A. FAYOLLE A. McDOWELL V. HUDÁK A. STUBB Directors: Messrs K.J. ANDREOPOULOS L. BARANYAY, also representing Mr NOWAK J. BLACK A. EBERHARDS F. GIANSANTE A. GYÖRGY M. HECTOR Ms V. IVANDIĆ Mr A. JACOBY Ms K. JORNA Messrs K. KAKOURIS A. KUNINGAS I. LESAY E. MASSÉ S. MIFSUD J. MORAN P. PAVELEK Ms M. PETROVA Ms K. RYSAVY Mr C. SAN BASILIO PARDO Ms K. SARJO Ms M. SCHOCH Ms J. SONNE Ms M. TUSKIENĖ Mr T. WESTPHAL Expert Members: Ms I. HENGSTER Messrs T. STONE A. PANGRATIS 3 Alternate Directors: Mr B. ANGEL (Present on 18 September 2017) Ms S. BELAJEC Ms S. BOBIN Messrs C. CUSCHIERI M. HEIPERTZ A. KAVČIČ * Ms F. MERCUSA Messrs R. MORTENSEN Ms S. SANYAHUMBI Messrs L. SARAMAGO ** P. TÁRNOKI-ZÁCH Ms J. TIKKANEN Messrs A. TZIMAS P-J. VAN STEENKISTE, representing Mr DESCHEEMAECKER Ms J. YOUNG Ms A. -

Dc Switchgear

DC SWITCHGEAR CITY ELECTRIC TRANSPORT ■ RAILWAYS ■ METRO ABOUT COMPANY PLUTON is one of the largest manufacturers of electrotechnical equipment in Europe. The company holds key position in electrical industry and has been successfully working for over 25 years, implementing the strategy of intensive growth, development and continuous improvement of products and services quality. More than 70 kinds of various equipment produced by PLUTON are supplied to many countries around the world and are successfully operated in the fields of transport, energy and industry. PLUTON Group of companies has representative offices in 9 countries of the world and continues dynamic development and expansion of its presence geography. The company confirmed compliance of its management principles with quality management system international standard ISO 9001:2015, Environmental Safety ISO 14001:2015, as well as occupational safety and health ISO 45001:2018 requirements. Due to vast experience and modern technologies we make secure, reliable and efficient energy distribution. We are building future, creating products of up- to- date level in compliance with international standards, innovative technologies that ensure safety and comfort of people. DC SWITCHGEAR PLUTON offers the best solutions in the field of energy distribution. We have developed switchgear, which provide reliable power supply and trouble-free control. We provide a full range of services starting with recommendations on switchgear components optimum choice and design, and up to installation and commissioning of the supplied equipment on operation site. We provide the following after switchgear start-up: • personnel correct and safe operation and maintenance training; • warranty maintenance; • post-warranty maintenance; • spare parts supply; • repairs. -

Ukraine: Your New Shared Service Center Destination

Ukraine: your new Shared Service Center v destination Looking for a new location? We can help Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 Executive summary 5 2. Why Ukraine is attractive to investors 6 3. Major locations for SSC 15 — Kyiv 16 — Lviv 22 — Ivano-Frankivsk 28 — Odesa 40 — Kharkiv 46 4. Overview of legal matters of doing business in Ukraine 52 About KPMG 54 © 2017 KPMG-Ukraine Ltd., a company incorporated under the Laws of Ukraine, a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative ("KPMG International"), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Does the right location matter for a successful shared services center (SSC)? The main idea behind SSC is moving major business operations from individual unit to a centralized location, where services are Ukraine: your new provided at a lower cost at the same or better quality. Productivity destination for BPO/SSC improvements and process quality resulting from centralization and standardization create additional benefits and increase competitiveness. As the speed of globalization keeps the growing momentum and technological advancement enables the companies to set up SSC capable of servicing around the globe from one place, the SSC model is attracting more resources and attention. Obviously, cost management and availability of required talent is the key matter for companies, which consider setting up SSC in a particular location. Right location is of utmost importance for the success of any SSC project. Clearly, investors mainly look for locations where human resources are less expensive and are also expected to be lower in the medium term.