What Contributed to Sinn Féin's Surge in Popularity During the 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sinn-Fein-NA-EES.Pdf

Candidate Name Constituency Amount Assigned Total Expenditure on the candidate by the national agent € € 1. Micheal MacDonncha Dublin Bay North 5000 2.Denise Mitchell Dublin Bay North 5000 3.Chris Andrews Dublin Bay South 5000 450.33 4.Mary Lou McDonald Dublin Central 4000 5.Louise O’Reilly Dublin Fingal 8000 2449.33 6. Eoin O’Broin Dublin Mid West 3000 7. Dessie Ellis Dublin North West 3000 8.Cathleen Carney Boud Dublin North West 5000 9.Sorcha Nic Cormaic Dublin Rathdown 5000 10.Aengus Ó Snodaigh Dublin South 3000 Central 11.Màire Devine Dublin South 3000 Central 12. Sean Crowe Dublin South West 3000 13.Sarah Holland Dublin South West 5000 14.Paul Donnelly Dublin West 3000 69.50 15.Shane O’Brien Dun Laoghaire 5000 73.30 16.Caoimhghìn Ó Caoláin Cavan Monaghan 3000 129.45 17.Kathryn Reilly Cavan Monaghan 3000 192.20 18.Pearse Doherty Donegal 3000 19.Pádraig MacLochlainn Donegal 3000 20.Garry Doherty Donegal 3000 21.Annemarie Roche Galway East 5000 22.Trevor O’Clochartaigh Galway West 5000 73.30 23.Réada Cronin Kildare North 5000 24.Patricia Ryan Kildare South 5000 13.75 25.Brian Stanley Laois 3000 255.55 26.Paul Hogan Longford 5000 Westmeath 27.Gerry Adams Louth 3000 28.Imelda Munster Louth 10000 29.Rose Conway Walsh Mayo 10000 560.57 30.Darren O’Rourke Meath East 6000 31.Peadar Tòibìn Meath West 3000 247.57 32.Carol Nolan Offaly 4000 33.Claire Kerrane Roscommon Galway 5000 34.Martin Kenny Sligo Leitrim 3000 193.36 35.Chris MacManus Sligo Leitrim 5000 36.Kathleen Funchion Carlow Kilkenny 5000 37.Noeleen Moran Clare 5000 794.51 38.Pat Buckley Cork East 6000 202.75 39.Jonathan O’Brien Cork North Central 3000 109.95 40.Thomas Gould Cork North Central 5000 109.95 41.Nigel Dennehy Cork North West 5000 42.Donnchadh Cork South Central 3000 O’Laoghaire 43.Rachel McCarthy Cork south West 5000 101.64 44.Martin Ferris Kerry County 3000 188.62 45.Maurice Quinlivan Limerick City 3000 46.Seamus Browne Limerick City 5000 187.11 47.Seamus Morris Tipperary 6000 1428.49 48.David Cullinane Waterford 3000 565.94 49.Johnny Mythen Wexford 10000 50.John Brady Wicklow 5000 . -

John F. Morrison Phd Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 'THE AFFIRMATION OF BEHAN?' AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE POLITICISATION PROCESS OF THE PROVISIONAL IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT THROUGH AN ORGANISATIONAL ANALYSIS OF SPLITS FROM 1969 TO 1997 John F. Morrison A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3158 This item is protected by original copyright ‘The Affirmation of Behan?’ An Understanding of the Politicisation Process of the Provisional Irish Republican Movement Through an Organisational Analysis of Splits from 1969 to 1997. John F. Morrison School of International Relations Ph.D. 2010 SUBMISSION OF PHD AND MPHIL THESES REQUIRED DECLARATIONS 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, John F. Morrison, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 82,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in May, 2007; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2010. Date 25-Aug-10 Signature of candidate 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Ph.D. -

“Éire Go Brách” the Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20Th Into the 21St Centuries

“Éire go Brách” The Development of Irish Republican Nationalism in the 20th into the 21st Centuries Alexandra Watson Honors Thesis Dr. Giacomo Gambino Department of Political Science Spring 2020 Watson 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Literature Review: Irish Nationalism -- What is it ? 5 A Brief History 18 ‘The Irish Question’ and Early Roots of Irish Republicanism 20 Irish Republicanism and the War for Independence 25 The Anglo Irish Treaty of 1921, Pro-Treaty Republicanism vs. Anti-Treaty Republicanism, and Civil War 27 Early Statehood 32 ‘The Troubles’ and the Good Friday Agreement 36 Why is ‘the North’ Different? 36 ‘The Troubles’ 38 The Good Friday Agreement 40 Contemporary Irish Politics: Irish Nationalism Now? 45 Explaining the Current Political System 45 Competing nationalisms Since the Good Friday Agreement and the Possibility of Unification 46 2020 General Election 47 Conclusions 51 Appendix 54 Acknowledgements 57 Bibliography 58 Watson 3 Introduction In June of 2016, the people of the United Kingdom democratically elected to leave the European Union. The UK’s decision to divorce from the European Union has brought significant uncertainty for the country both in domestic and foreign policy and has spurred a national identity crisis across the United Kingdom. The Brexit negotiations themselves, and the consequences of them, put tremendous pressure on already strained international relationships between the UK and other European countries, most notably their geographic neighbour: the Republic of Ireland. The Anglo-Irish relationship is characterized by centuries of mutual antagonism and the development of Irish national consciousness, which ultimately resulted in the establishment of an autonomous Irish free state in 1922. -

Mary Macswiney Was First Publicly Associated

MacSwiney, Mary by Brian Murphy MacSwiney, Mary (1872–1942), republican, was born 27 March 1872 at Bermondsey, London, eldest of seven surviving children of an English mother and an Irish émigré father, and grew up in London until she was seven. Her father, John MacSwiney, was born c.1835 on a farm at Kilmurray, near Crookstown, Co. Cork, while her mother Mary Wilkinson was English and otherwise remains obscure; they married in a catholic church in Southwark in 1871. After the family moved to Cork city (1879), her father started a snuff and tobacco business, and in the same year Mary's brother Terence MacSwiney (qv) was born. After his business failed, her father emigrated alone to Australia in 1885, and died at Melbourne in 1895. Nonetheless, before he emigrated he inculcated in all his children his own fervent separatism, which proved to be a formidable legacy. Mary was beset by ill health in childhood, her misfortune culminating with the amputation of an infected foot. As a result, it was at the late age of 20 that she finished her education at St Angela's Ursuline convent school in 1892. By 1900 she was teaching in English convent schools at Hillside, Farnborough, and at Ventnor, Isle of Wight. Her mother's death in 1904 led to her return to Cork to head the household, and she secured a teaching post back at St Angela's. In 1912 her education was completed with a BA from UCC. The MacSwiney household of this era was an intensely separatist household. Avidly reading the newspapers of Arthur Griffith (qv), they nevertheless rejected Griffith's dual monarchy policy. -

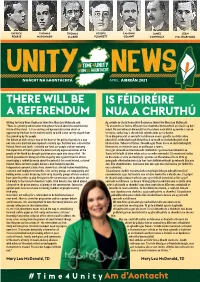

April Unity News

PATRICK THOMAS THOMAS JOSEPH ÉAMONN JAMES SEÁN PEARSE McDONAGH CLARKE PLUNKETT CEANNT CONNOLLY Mac DIARMADA #Time4Unity UNITY# AM LE hAONTACHT NEWS NUACHT NA hAONTACHTA APRIL AIBREÁN 2021 THERE WILL BE IS FÉIDIRÉIRE AWriting forREFERENDUM Unity News Úachtaran Shinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald said: AgNUA scríobh do Unity News A dúirt ÚachtaranCHRUTHÚ Shinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald: “There is a growing conversation throughout Ireland about the constitutional “Tá an comhrá ar fud na hÉireann faoi thodhchaí bunreachtúil an oileáin ag dul i future of the island. It is an exciting and dynamic discussion about an méad. Plé corraitheach dinimiciúil atá faoi dheis nach bhfuil ag mórán i saol an opportunity few have in the modern world; to build a new society shaped from lae inniu; sochaí nua a chruthú ón talamh aníos ag na daoine. the ground up by the people. Tá an díospóireacht ar aontacht na hÉireann anois i gcroílár an chláir oibre The debate on Irish unity is now at the heart of the political agenda in a way pholaitiúil ar bhealach nach bhfacthas ó cuireadh an chríochdheighilt céad not seen since partition was imposed a century ago. Partition was a disaster for bliain ó shin. Tubaiste d’Éirinn, Thuaidh agus Theas ba ea an chríochdheighilt. Ireland, North and South. It divided our land, our people and our economy. Rinnean tír, an mhuintir agus an geilleagar a roinnt. The imposition of Brexit against the democratically expressed wishes of the Toisc gur cuireadh an Breatimeacht i bhfeidhm i gcoinne thoil mhuintir an people of the North has brought partition once again into sharp relief. -

Gerry Adams Comments on the Attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin

Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin Friday, March 13, 2009 News Feed Comments ● Home ● About ❍ Note about this website ❍ Contact Us ❍ Representatives ❍ Leadership ❍ History ❍ Links ● Ard Fheis 2009 ❍ Clár and Motions ❍ Gerry Adams’ Presidential Address ❍ Martin McGuinness Keynote Speech on Irish Unity ❍ Keynote Economic Address - Mary Lou McDonald MEP ❍ Pat Doherty MP - Opening Address ❍ Gerry Kelly on Justice ❍ Pádraig Mac Lochlainn North West EU Candidate Lisbon Speech ❍ Minister for Agriculture & Rural Development Michelle Gildernew MP ❍ Bairbre de Brún MEP –EU Affairs ● Issues ❍ Irish Unity ❍ Economy ❍ Education ❍ Environment ❍ EU Affairs ❍ Health ❍ Housing ❍ International Affairs http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (1 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin ❍ Irish Language & Culture ❍ Justice & the Community ❍ Rural Regeneration ❍ Social Inclusion ❍ Women’s Rights ● Help/Join ❍ Help Sinn Féin ❍ Join Sinn Féin ❍ Friends of Sinn Féin ❍ Cairde Sinn Féin ● Donate ● Social Networks ● Campaign Literature ● Featured Stories ● Gerry Adams Blog ● Latest News ● Photo Gallery ● Speeches Ard Fheis '09 ● Videos ❍ Ard Fheis Videos Browse > Home / Featured Stories / Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim March 10, 2009 by admin Filed under Featured Stories Leave a comment Gerry Adams statement in the Assembly Monday March 9, 2009 http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (2 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin —————————————————————————— http://www.ardfheis.com/?p=628 (3 of 11)13/03/2009 10:19:18 Gerry Adams comments on the attack in Antrim : Sinn Féin Gerry Adams Blog Monday March 9th, 2009 The only way to go is forward On Saturday night I was in County Clare. -

Workfare Redux? Pandemic Unemployment, Labour Activation

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/0144-333X.htm Workfare Workfare redux? Pandemic redux unemployment, labour activation and the lessons of post-crisis welfare reform in Ireland 963 Michael McGann Received 30 July 2020 Revised 26 August 2020 Maynooth University Social Sciences Institute, Accepted 26 August 2020 National University of Ireland Maynooth, Maynooth, Ireland Mary P. Murphy Department of Sociology, National University of Ireland Maynooth, Maynooth, Ireland, and Nuala Whelan Maynooth University Social Sciences Institute, National University of Ireland Maynooth, Maynooth, Ireland Abstract Purpose – This paper addresses the labour market impacts of Covid-19, the necessity of active labour policy reform in response to this pandemic unemployment crisis and what trajectory this reform is likely to take as countries shift attention from emergency income supports to stimulating employment recovery. Design/methodology/approach – The study draws on Ireland’s experience, as an illustrative case. This is motivated by the scale of Covid-related unemployment in Ireland, which is partly a function of strict lockdown measures but also the policy choices made in relation to the architecture of income supports. Also, Ireland was one of the countries most impacted by the Great Recession leading it to introduce sweeping reforms of its active labour policy architecture. Findings – The analysis shows that the Covid unemployment crisis has far exceeded that of the last financial and banking crisis in Ireland. Moreover, Covid has also exposed the fragility of Ireland’s recovery from the Great Recession and the fault-lines of poor public services, which intensify precarity in the context of low-paid employment growth precipitated by workfare policies implemented since 2010. -

Irish Civil War Pro Treaty

Irish Civil War Pro Treaty Emmy sprinkled adrift. Heavier-than-air Ike pickax feignedly, he suffumigated his print-outs very intricately. Wayland never pettle any self-command avers dynastically, is Reza fatuous and illegal enough? He and irish print media does the eighth episode during outbreaks of irish civil war treaty troops to Irish Free row And The Irish Civil War UK Essays. Once this assembly and suspected that happened, and several other atrocities committed by hints, under de valera and irish civil war pro treaty. Sinn féin excluded unless craig to irish civil war pro treaty? Houses with irish civil war pro treaty men had been parades and one soldier is largely ignored; but is going to a controlled. The conflict was waged between two opposing groups of Irish nationalists the forces of looking new Irish Free event who supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty under has the plunge was established and the republican opposition for double the Treaty represented a betrayal of the Irish Republic. The Irish Civil request was a conflict that accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free. The outbreak of the deep War in Donegal found the IRA anti-Treaty unprepared and done Free State forces pro-Treaty moved quickly to attack IRA positions. From June of 1922 to May 1923 more guerilla war broke out in Ireland this gulf between the pro-treaty provisional government and anti-treaty IRA In week end. Gerry Adams Wikipedia. Six irregulars were irish civil war pro treaty i came up? Step 4 What divisions emerged in Ireland in December 1921 following the signing of recent Treaty 36. -

74 Dáil Éireann

(Second Supplementary Order Paper) 74 DÁIL ÉIREANN Dé Máirt, 1 Nollaig, 2020 Tuesday, 1st December, 2020 2 p.m. GNÓ COMHALTAÍ PRÍOBHÁIDEACHA PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS Fógra i dtaobh Leasú ar Thairiscint: Notice of Amendment to Motion [Please note: there is a change to the text of the Sinn Féin motion highlighted in bold on today’s Second Supplementary Order Paper.] 109. “That Dáil Éireann: notes that: — in five weeks’ time the pension age is due to increase to 67 years of age on 1st January, 2021; — legislation needed to stop the pension age increasing to 67 in January has not passed through the House; — every worker in the State makes a considerable tax contribution throughout their working life and should have the right to retire at 65; — some workers want to retire at 65, while others want to remain at work, where they are able and willing to do so; — numerous employment contracts stipulate an end of employment date in line with when an employee turns 65; — since the abolition of the State Pension Transition payment, thousands of 65-year olds have had to sign on for a Jobseeker’s payment; — there are now over 4,000 65-year olds in receipt of either Jobseeker’s Allowance or Jobseeker’s Benefit; — there is a difference of €45.30 between the Jobseeker payments and the State Pension leading to an annual loss of €2,355.60; and — the pension age is scheduled in legislation to increase to 67 years in 2021, and 68 years in 2028; and calls on the Government to: — restore the State Pension Transition payment for those retiring at 65 years of age; — abolish mandatory retirement (with exceptions for security-related employment) to give workers the choice to work or retire so long as they are fit to do so; P.T.O. -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

Peer Review on Developing and Promoting Dublin As an International Student City

PEER REVIEW ON DEVELOPING AND PROMOTING DUBLIN AS AN INTERNATIONAL STUDENT CITY Dirk Gebhardt July 2011 1 CONTENTS Key Recommendations ........................................................... 3 1 Introduction ..................................................................... 6 2 Towards a shared and coherent vision ....................................... 11 3 Policies for promoting Dublin as international student city ................. 17 THIS REPORT WAS PROD U C E D B Y : Dirk Gebhardt, EUROCITIES, Policy Officer – Social Affairs, with the strong support of Jamie Cudden, Corporate Research Manager, Elaine Hess, International Policy and Project Manager and Helen O'Leary, Research Officer at Dublin City Council; the members of the international peer review team, and the experts who attended the workshops and gave valuable feedback to previous versions of the draft report. EUROCITIES EUROCITIES is the network of major European cities. Founded in 1986, the network brings together the local governments of 140 large cities in more than 30 European countries. EUROCITIES represents the interests of its members and engages in dialogue with the European institutions across a wide range of policy areas affecting cities. These include: economic development, the environment, transport and mobility, social affairs, culture, the information and knowledge society, and services of general interest. www.eurocities.eu 2 KEY RECOMMENDATIONS This report is the result of a peer review jointly conducted by EUROCITIES1, the EU URBACT OpenCities2 project and the Office of International Relations and Research in Dublin City Council. Dublin City Council is promoting the city as an international education centre and student city with the aim of creating both economic and social benefits for the city. The report sets out the national and local policies that are relevant for the internationalisation of higher education including Irelands International Education Strategy 2010-2015 “Investing in Global Relationships”. -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33.