The Varney Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribal and House District Boundaries

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribal Boundaries and Oklahoma House Boundaries ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 22 ! 18 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 13 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 20 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 7 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cimarron ! ! ! ! 14 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 11 ! ! Texas ! ! Harper ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! n ! ! Beaver ! ! ! ! Ottawa ! ! ! ! Kay 9 o ! Woods ! ! ! ! Grant t ! 61 ! ! ! ! ! Nowata ! ! ! ! ! 37 ! ! ! g ! ! ! ! 7 ! 2 ! ! ! ! Alfalfa ! n ! ! ! ! ! 10 ! ! 27 i ! ! ! ! ! Craig ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! h ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 26 s ! ! Osage 25 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 16 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 21 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 58 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 38 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tribes by House District ! 11 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Absentee Shawnee* ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Woodward ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2 ! 36 ! Apache* ! ! ! 40 ! 17 ! ! ! 5 8 ! ! ! Rogers ! ! ! ! ! Garfield ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 40 ! ! ! ! ! 3 Noble ! ! ! Caddo* ! ! Major ! ! Delaware ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! Mayes ! ! Pawnee ! ! ! 19 ! ! 2 41 ! ! ! ! ! 9 ! 4 ! 74 ! ! ! Cherokee ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ellis ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 41 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 72 ! ! ! ! ! 35 4 8 6 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 5 3 42 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 77 -

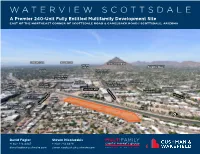

Waterview Scottsdale

WATERVIEW SCOTTSDALE A Premier 240-Unit Fully Entitled Multifamily Development Site EAST OF THE NORTHEAST CORNER OF SCOTTSDALE ROAD & CAMELBACK ROAD | SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA DOWNTOWN PHOENIX MIDTOWN PHOENIX CAMELBACK MOUNTAIN CAMELBACK CORRIDOR PARADISE VALLEY ARCADIA PHOENICIAN RESORT & GOLF COURSE OPTIMA SONORAN VILLAGE CONDOS SCOTTSDALE PORTALES OPTIMA CAMELVIEW FINANCIAL CENTER OLD TOWN SCOTTSDALE FASHION CENTER VILLAGE CONDOS SCOTTSDALE WATERFRONT CHAPARRAL SUITES SCOTTSDALE ROAD HIGHLAND AVENUE FIRESKY GALLERIA RESORT & SPA SCOTTSDALE CORPORATE CENTER SAFARI DRIVE CHAPARRAL ROAD W HOTEL PLANNED CONDOS 5 STAR HOTEL DOWNTOWN SCOTTSDALE CAMELBACK ROAD ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT SAGE SCOTTSDALE David Fogler Steven Nicoluzakis +1 602 224 4443 +1 602 224 4429 [email protected] [email protected] WATERVIEW SCOTTSDALE THE OFFERING Cushman & Wakefield is pleased to present a unique opportunity to purchase a 240-unit premier, entitled multifamily development site in Downtown Scottsdale’s prestigious waterfront district. This rare site is located along the Arizona Canal, within walking distance of Scottsdale Fashion Square and Downtown Scottsdale’s world class Entertainment District with its vibrant nightlife. This is truly the best development site currently available in Arizona. The opportunity consists of approximately 6.1 gross/5.3 net acres of developable land located east of the northeast corner of Scottsdale Road and Camelback Road. This fully entitled development site is approved for 240 residential units and four stories. Today’s generation of “by choice renters” are looking for a unique and central living environment. WaterView Scottsdale is that exceptional site, providing all of that and more. Located just east of Scottsdale’s premier intersection of Scottsdale and Camelback Roads with frontage along the Arizona Canal, the site offers prestige, convenience and walkability to the best shopping, dining, entertainment venues and workplace spaces in Arizona. -

Myaamia Storytelling and Living Well: an Ethnographic Examination

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2019 Myaamia storytelling and living well: An ethnographic examination Haley Alyssa Shea Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Counseling Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Shea, Haley Alyssa, "Myaamia storytelling and living well: An ethnographic examination" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 17561. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/17561 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Myaamia storytelling and living well: An ethnographic examination by Haley Alyssa Shea A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Psychology (Counseling Psychology) Program of Study Committee: David L. Vogel, Major Professor Christina Gish-Hill Meifen Wei Warren Phillips Tera Jordan The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this dissertation. The Graduate College will ensure this dissertation is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is -

The Great Banquet Retreat As a Strategy to Transform Northminster Presbyterian Church

Please HONOR the copyright of these documents by not retransmitting or making any additional copies in any form. We appreciate your respectful cooperation. ___________________________ Theological Research Exchange Network (TREN) P.O. Box 30183 Portland, Oregon 97294 USA Website: www.tren.com E-mail: [email protected] Phone# 1-800-334-8736 THE GREAT BANQUET RETREAT AS A STRATEGY TO TRANSFORM NORTHMINSTER PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH A MINISTRY FOCUS PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY FULLER THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY DOUG HUCKE MARCH 2008 The Great Banquet Retreat as a Strategy to Transform Northminster Presbyterian Church Doug Hucke Doctor of Ministry 2008 School of Theology, Fuller Theological Seminary The purpose of this ministry focus paper is to present a culturally appropriate and theologically informed strategy to renew Northminster Presbyterian Church by incorporating the Great Banquet (a Presbyterian adaptation of the Cursillo Model renewal weekend) into the life and ministry of the church. The Great Banquet is a seventy-two- hour structured retreat, beginning Thursday evening and ending Sunday evening. The Great Banquet also includes a time of preparation and follow-up that are critically important. North American culture is transitioning from modernity to postmodernity. The transition to postmodernity is not complete, and Americans find themselves in a transitional stage with a great deal of stress and uncertainty. Church renewal is very difficult in this time of transition. The Great Banquet is a ministry tool that is uniquely effective in renewal in this transitional time. This paper contains three major parts. -

Arizona Biltmore Resort &

ARIZONA BILTMORE RESORT & SPA PLANNED UNIT DEVELOPMENT Z-71-08-6 Volume 1: Existing Conditions & Master Plans July 2009 Project Team Developer: Landscape Architect Pyramid Project Management LVA Urban Design Studio, LLC Ken Hoeppner Joe Young Doug Cole 120 S. Ash Avenue One Post Office Square, Ste. 3100 Tempe, AZ 85281 Boston, MA 02109 480.994.0994 617.412.2839 Civil Engineering & Traffic: Property Manager: Kimley-Horn & Associates, INC Arizona Biltmore Resort & Spa David Morris Andrew Stegen Tove White 2400 East Missouri 7878 N. 16th Street, Ste. 300 Phoenix, AZ 85016 Phoenix, AZ 85020 602.381.7634 602.944.5500 Legal: Land Planner: Snell & Wilmer, LLP LVA Urban Design Studio, LLC Nick Wood Alan Beaudoin One Arizona Center Jon Vlaming Phoenix, AZ 85004 120 S. Ash Avenue 602.382.6000 Tempe, AZ 85281 480.994.0994 Historic Preservation: Akros Inc. Public Relations: Debbie Abele Denise Resnick & Associates Jim Coffman Denise Resnick 502 S. College Avenue, Ste 311 Jeff Janas Tempe, AZ 85281 5045 N. 12th Street, Ste 110 480.774.2902 Phoenix, AZ 85014 602.956.8834 Architect & Signs: Gensler Technical Solutions Claudia Carol Paul Smith Amy Owen Sarah Dorn 2500 Broadway, Suite 300 3875 N. 44th Street, Ste 300 Santa Monica, CA 90404 Phoenix, AZ 85018 310.449.5600 602.957.3434 Lighting: Lighting Design Collaborative Landscape Architect/Master Plans John Sarkioglu EDSA Gary Garofalo Stephen Poe 1216 Arch St. 1520-A Cloverfield Blvd. Philadelphia, PA 19107 Santa Monica, CA 90404 215.569.2115 310.435.8853 July 2009 ARIZONA BILTMORE RESORT AND SPA Planned Unit Development Volume I: Existing Conditions & Master Plans Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ -

EASTERN CANAL South Side of Salt River Mesa Vicinity Maricopa

5 i EASTERN CANAL HAER AZ-56 South side of Salt River AZ-56 Mesa vicinity Maricopa County Arizona PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD INTERMOUNTAIN REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 12795 West Alameda Parkway Denver, CO 80228 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD EASTERN CANAL Location: On the south side of the Salt River, extending through the City of Mesa and Town of Gilbert in Maricopa County, Arizona. USGS Mesa and Gila Butte Quadrangles Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: Head: 427,708.5342E- 3,703,121.3135N Foot: 426,245.1880E- 3,675,675.1940N Dates of Construction: March-December 1909. Engineer: U.S. Reclamation Service. Present Owner: U.S. Government, operated by Salt River Project (SRP), Phoenix, Arizona. Present Use: The Eastern Canal carries water for agricultural, industrial, and municipal uses in the southeast portion of the Salt River Project. Significance: The Eastern Canal expanded the irrigable acreage of the Salt River Project and currently supplies water for the Roosevelt Water Conservation District (RWCD). It was the first SRP canal constructed by local landowners under the cooperative plan. Historian: Marc C. Campbell SRP Research Archives EASTERN CANAL HAER No. AZ-56 (Page 2) Table of Contents Introduction 3 Early Irrigation in the Salt River Valley 3 The Highland Canal 5 Federal Reclamation and the Highland Canal 6 Building a Reincarnated Highland: The Eastern Canal 11 Enlarging the Eastern 15 The Contract with Roosevelt Water Conservation District 17 The Civilian Conservation Corps 21 Rehabilitation and Betterment (R&B) 21 The Eastern to the Present 23 Bibliography 26 Maps 29 EASTERN CANAL HAER No. -

Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in This Edition of Newspapers in Education

he American Indian Cultural Center and Museum (AICCM) is honored Halito! Oklahoma has a unique history that differentiates it from any other Tto present, in partnership with Newspapers In Education at The Oklahoman, state in the nation. Nowhere else in the United States can a visitor hear first the Native American Heritage educational workbook. Workbooks focus on hand-accounts from 39 different American Indian Tribal Nations regarding the cultures, histories and governments of the American Indian tribes of their journey from ancestral homelands, or discover how Native peoples have Oklahoma. The workbooks are published twice a year, around November contributed and woven their identities into the fabric of contemporary Oklahoma. and April. Each workbook is organized into four core thematic areas: Origins, Oklahoma is deeply rooted in American Indian history and heritage. We hope Native Knowledge, Community and Governance. Because it is impossible you will use this guide to explore our great state and to learn about Okla- to cover every aspect of the topics featured in each edition, we hope the Humma. (“Red People” in the Choctaw language.)–Gena Timberman, Esq., workbooks will comprehensively introduce students to a variety of new subjects and ideas. We hope you will be inspired to research and find out more information with the help of your teachers and parents as well as through your own independent research. The American Indian Cultural Center and Museum would like to give special thanks to the Oklahoma Tourism & Recreation Department for generously permitting us to share information featured in the Oklahoma Indian Country Guide in this edition of Newspapers in Education. -

Tribal Jurisdictions in Oklahoma

TRIBAL JURISDICTIONS IN OKLAHOMA IKE 385 69 P 59 N 325 R 23 U 83 283 183 CHILOCCO35 INDIAN 169 T 8 81 18 44 54 281 SCHOOL LANDS 75 56 10 NOWATA 136 64 132 95 10 59 10C TEXAS 64 11 KAW WOODS GRANT 177 64 KAY ALFALFA 11A OSAGE 64 58 99 DELAWARE TRIBE 25 OTTAWA 325 412 94 11 11 11 60 64 OF INDIANS 10 64 BEAVER CIMARRON HARPER 11 CRAIG 125 74 2 171 50 77 RS 270 60 GE 3 149 RO L 38 IL 14 385 60 W 69 60 28 60 95 TONKAWA N 136 64 64 59 54 3 183 123 O 412 270 34 25 8 T 287 54 PONCA 83 OSAGE G 82 45 N 59 I 66 23 CHEROKEE 283 64 156 11 H 45 15 177 S 46 169 A ROGERS 270 75 28 W 45 28 34C 50B 15 15 20 20 15 OTOE - E K NOBLE 77 66 I MISSOURIA P MAYES 15 88 N 60 R WOODWARD 60 64 U 20 281 CIMARRON 20 44 T 69 59 15 50 412 PAWNEE 74 99 58 412 20 34 MAJOR DELAWARE 116 64 64 S 164 R 18 E 69A G 88 TURNPIKE PAWNEE O 412A TURNPIKE 266 R 412B 8 L CHEROKEE GARFIELD 412 L 412 183 60 I 412A 132 81 W 58 35 412 E 82 108 244 K I 60 P 60 132 N 51A R 51 51 U 51 51 T ELLIS 97 44 10 281 45 51 TULSA M ADAIR 99 48 U 8 KINGFISHER 74D 177 18 EK SK RE O Inset of Northeast Corner PAYNE C GE 82 77 CREEK E 283 E IK 62 81 33 P CHEROKEE N WAGONER E 33 R 64 LOGAN U 51 59 K 34 58 T I TU P 74C R R 51 DEWEY E 66 NP 183 N IK 80 UNITED KEETOOWAH N 8A R 75 E U 69 51 69A R IOWA 16 T 72 16 BAND OF CHEROKEES U 51B T 105 105 3 QUAPAW 47 33 MUSCOGEE (CREEK) 104 100 33 62 82 MIAMI 69 47 66 44 270 74F 44 75A 30 177 35 M 47 81 74 16 64 16 U E NPIK 165 S TUR 66 K ROGER CUSTER O 100 44 G 10 33 52 E MILLS BLAINE SAC AND FOX E 33 283 54 4 66 R RNE MUSKOGEE 47 TU 56 T 10A CHEYENNE - ARAPAHO TURNPIKE -

Map of Indian Lands in the United States

132°W 131°W 130°W 129°W 128°W 127°W 126°W 125°W 124°W 123°W 122°W 121°W 120°W 119°W 118°W 117°W 116°W 115°W 114°W 113°W 112°W 111°W 110°W 109°W 108°W 107°W 106°W 105°W 104°W 103°W 102°W 101°W 100°W 99°W 98°W 97°W 96°W 95°W 94°W 93°W 92°W 91°W 90°W 89°W 88°W 87°W 86°W 85°W 84°W 83°W 82°W 81°W 80°W 79°W 78°W 77°W 76°W 75°W 74°W 73°W 72°W 71°W 70°W 69°W 68°W 67°W 66°W 65°W 64°W 63°W 48°N 46°N 47°N Neah Bay 4 35 14 45°N Everett 46°N Taholah CANADA Seattle Nespelem 40 Aberdeen 44°N Wellpinit Browning Spokane 45°N Harlem Belcourt WAS HIN Box Wagner E GTO Plummer Elder IN N MA 10 Pablo E SUPER Wapato IO Poplar K R Toppenish A 43°N New L Town Fort Totten Red Lake NT 44°N O Lapwai RM Portland VE Sault MO Sainte Marie NTANA Cass Lake Siletz Pendleton 42°N K NH NORTH DAKOTA Ashland YOR EW 43°N W N arm Sp L ring A s KE No H r Fort U th Yates Boston w Billings R TTS e Crow E 41°N s Age O S t ncy HU Worcester O R N AC RE eg Lame Deer OTA NTARIO SS GON io MINNES E O MA 42°N n Sisseton K A Providence 23 Aberdeen L N I 39 Rochester R A Springfield Minneapolis 51 G Saint Paul T SIN I C WISCON Eagl e H 40°N IDA Butte Buffalo Boise HO C I 6 41°N R M o E cky M SOUTH DAKOTA ou K AN ntai ICHIG n R A M egion Lower Brule Fort Thompson L E n Grand Rapids I io New York g 39°N e Milwaukee R Fort Hall R west 24 E d Detroit Mi E 40°N Fort Washakie K WYOMING LA Rosebud Pine Ridge Cleveland IA Redding Wagner AN Toledo LV 32 NSY PEN Philadelphia 38°N Chicago NJ A 39°N IOW Winnebago Pittsburgh Fort Wayne Elko 25 Great Plains Region Baltimore Des Moines MD E NEBRASKA OHIO -

American Indians in Oklahoma OKLAHOMA HISTORY CENTER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT

American Indians in Oklahoma OKLAHOMA HISTORY CENTER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Nawa! That means hello in the Pawnee language. In Oklahoma, thirty-eight federally recognized tribes represent about 8 percent of the population. Most of these tribes came from places around the country but were removed from their homelands to Oklahoma in the nineteenth century. Their diverse cultures and rich heritage make Oklahoma (which combines the Choctaw words “okla” and “huma,” or “territory of the red people”) a special state. American Indians have impacted Oklahoma’s growth from territory to statehood and have made it into the great state it is today. This site allows you to learn more about American Indian tribes in Oklahoma. First, read the background pages for more information, then go through the biographies of influential American Indians to learn more about him or her. The activities section has coloring sheets, games, and other activities, which can be done as part of a group or on your own. Map of Indian Territory prior to 1889 (ITMAP.0035, Oklahoma Historical Society Map Collection, OHS). American Indians │2016 │1 Before European Contact The first people living on the prairie were the ancestors of various American Indian tribes. Through archaeology, we know that the plains have been inhabited for centuries by groups of people who lived in semi-permanent villages and depended on planting crops and hunting animals. Many of the ideas we associate with American Indians, such as the travois, various ceremonies, tipis, earth lodges, and controlled bison hunts, come from these first prairie people. Through archaeology, we know that the ancestors of the Wichita and Caddo tribes have been in present-day Oklahoma for more than two thousand years. -

Congressional Record-Senate. 597

..; . 1887. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 597 burg, Va., in favor of the repeal of the internal-revenue taxon tobacco; Mary Lathrop; and to Mrs. Mary Jane Case-to the Committee on In and for rebate should said tax be removed-to the Committee on Ways valid Pensions. - · and Means. By Mr. WARD: Resolutions adopted by the Illinois Stat.e board of · By Mr. W. C. P. BRECKINRIDGE: Petition of a chamber of com agriculture, relating to the suppression of pleuro-pneumoma-to the merce for appropriation for coast defense-to the Committee on Appro Committee on Agriculture. priations. By Mr. A. J. WARNER: Petition of E. B. Beebe, for investigation By Mr. BUNNELL: Petition of 121citizens of theFifteenthdistrict into conspiracy of cert.<tin banks-to the Committee on Banking and of Pennsylvania, in favor of the Blair bill-to the Committee on Edu Currency. _ cation. By Mr. A . C. WHITE: Petition of 581 citizens of the twenty-fifth Also, papers to accompany the bill (H. R. 10591) for the relief of the district of Pennsylvania, in favor of the Blair bill-to the Committee heirs of Percival Powell, deceased, late postmast~r at Towanda, Brad on Education. ford County, Pennsylvania-to the Committee on Claims. By Mr. WILLIS: Petition of Weissinger & Bate, Finzer & Bro., and By Mr. J. :M. CAMPBELL: Petition of Berry F. Kinsey, for a other tobacco manufacturers, for the repeal of the tobacco tax-to the special-act pension-to the Committee on Invalid Pensions. Committee on Ways and Means. By Mr. CLEMENTS: Papers relating to the claim of Cm·tis Bailey, of Floyd County, Georgia-to the Committee on War Claims. -

^ I ^He Peoria of Oklahoma Have a X Long and Complicated History. The

Peoria 135 PEORIA ^ I ^he Peoria of Oklahoma have a X long and complicated history. The Peoria are a band of the Illinois tribe, which was considered one of the westernmost parts of the Algonquin people. By 1833, continued encroachment by the white man forced the Peoria, along with their fellow band of Illinois, the Kaskaskias, to move west to present-day Nebraska and Kansas. There they joined with two Miami bands, the Weas and the Piankashaws. These four bands, later relocated to what is now north• eastern Oklahoma, are now known as the Peoria Tribe of Oklahoma {Official Emblem of the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, flyer, n.d., Peoria Tribe of Oklahoma). The flag of the Peoria of Oklahoma reflects this history. The seal of the Peoria Nation appears on a white background. On a red disk, which recalls the trials of the ancestors of the Peoria, is a large arrowhead, colored white on the flag but depicted in natural colors when used as a seal (Annin & Co.). The large arrowhead, pointing downward as a sign of peace, represents the present generation of the Peoria people and their promise to work as individuals and as a tribe to cherish, honor, and preserve the heritage and customs left to them by preceding generations. The two emblems—the disk and the arrowhead—combine to mean that the Peoria will live in peace but will be suppressed by no one. Four arrows cross the large arrowhead to form two overlapping "X"s: turquoise for the Piankashaws and the native soil; red for the Peorias and the sun; blue for the Weas and the waters; and green for the Kaskaskias and the grass and trees.