EASTERN CANAL South Side of Salt River Mesa Vicinity Maricopa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World's Major Rivers

WWWWWWoorrlldd’’ss mmaajjoorr rriivveerrss AAnn IInnttrroodduuccttiioonn ttoo iinntteerrnnaattiioonnaall wwwwwwaatteerr llaawwwwww wwwwwwiitthh ccaassee ssttuuddiieess THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK WWWWWWoorrlldd’’ss mmaajjoorr rriivveerrss An introduction to international water law with case studies Colorado River Commission of Nevada 555 E. Washington Avenue, Suite 3100 Las Vegas, Nevada 89101 Phone: (702) 486-2670 Website: http://crc.nv.gov November 2008 Jacob (Jay) D. Bingham, Chairman Ace I. Robinson, Vice Chairman Andrea Anderson, Commissioner Marybel Batjer, Commissioner Chip Maxfield, Commissioner George F. Ogilvie III, Commissioner Lois Tarkanian, Commissioner George M. Caan, Executive Director Primary Author: Daniel Seligman, Attorney at Law Columbia Research Corp. P.O. Box 99249 Seattle, Washington 98139 (206) 285-1185 Project Editors: McClain Peterson, Project Manager Manager, Natural Resource Division Colorado River Commission of Nevada Sara Price Special Counsel-Consultant Colorado River Commission of Nevada Esther Valle Natural Resource Analyst Colorado River Commission of Nevada Nicole Everett Natural Resource Analyst Colorado River Commission of Nevada THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK World’s Major Rivers ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Daniel Seligman at the Columbia Research Corp. wishes to thank Jacqueline Pruner, attorney at law in Seattle, for her contribution to the section on water law in Canada and her valuable editing assistance throughout the entire document. The staff at the Murray-Darling Basin Commission and Goulburn-Murray Water in Australia provided important information about the Murray-Darling River system, patiently answered the author’s questions, and reviewed the draft text on water trading. Staff at the International Joint Commission in Washington, D.C., and the Prairie Provinces Water Board in Regina, Canada, also offered helpful comments on an earlier draft. -

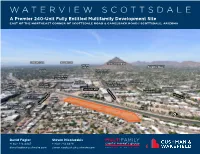

Waterview Scottsdale

WATERVIEW SCOTTSDALE A Premier 240-Unit Fully Entitled Multifamily Development Site EAST OF THE NORTHEAST CORNER OF SCOTTSDALE ROAD & CAMELBACK ROAD | SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA DOWNTOWN PHOENIX MIDTOWN PHOENIX CAMELBACK MOUNTAIN CAMELBACK CORRIDOR PARADISE VALLEY ARCADIA PHOENICIAN RESORT & GOLF COURSE OPTIMA SONORAN VILLAGE CONDOS SCOTTSDALE PORTALES OPTIMA CAMELVIEW FINANCIAL CENTER OLD TOWN SCOTTSDALE FASHION CENTER VILLAGE CONDOS SCOTTSDALE WATERFRONT CHAPARRAL SUITES SCOTTSDALE ROAD HIGHLAND AVENUE FIRESKY GALLERIA RESORT & SPA SCOTTSDALE CORPORATE CENTER SAFARI DRIVE CHAPARRAL ROAD W HOTEL PLANNED CONDOS 5 STAR HOTEL DOWNTOWN SCOTTSDALE CAMELBACK ROAD ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT SAGE SCOTTSDALE David Fogler Steven Nicoluzakis +1 602 224 4443 +1 602 224 4429 [email protected] [email protected] WATERVIEW SCOTTSDALE THE OFFERING Cushman & Wakefield is pleased to present a unique opportunity to purchase a 240-unit premier, entitled multifamily development site in Downtown Scottsdale’s prestigious waterfront district. This rare site is located along the Arizona Canal, within walking distance of Scottsdale Fashion Square and Downtown Scottsdale’s world class Entertainment District with its vibrant nightlife. This is truly the best development site currently available in Arizona. The opportunity consists of approximately 6.1 gross/5.3 net acres of developable land located east of the northeast corner of Scottsdale Road and Camelback Road. This fully entitled development site is approved for 240 residential units and four stories. Today’s generation of “by choice renters” are looking for a unique and central living environment. WaterView Scottsdale is that exceptional site, providing all of that and more. Located just east of Scottsdale’s premier intersection of Scottsdale and Camelback Roads with frontage along the Arizona Canal, the site offers prestige, convenience and walkability to the best shopping, dining, entertainment venues and workplace spaces in Arizona. -

Dams on the Mekong

Dams on the Mekong A literature review of the politics of water governance influencing the Mekong River Karl-Inge Olufsen Spring 2020 Master thesis in Human geography at the Department of Sociology and Human Geography, Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Words: 28,896 08.07.2020 II Dams on the Mekong A literature review of the politics of water governance influencing the Mekong River III © Karl-Inge Olufsen 2020 Dams on the Mekong: A literature review of the politics of water governance influencing the Mekong River Karl-Inge Olufsen http://www.duo.uio.no/ IV Summary This thesis offers a literature review on the evolving human-nature relationship and effect of power struggles through political initiatives in the context of Chinese water governance domestically and on the Mekong River. The literature review covers theoretical debates on scale and socionature, combining them into one framework to understand the construction of the Chinese waterscape and how it influences international governance of the Mekong River. Purposive criterion sampling and complimentary triangulation helped me do rigorous research despite relying on secondary sources. Historical literature review and integrative literature review helped to build an analytical narrative where socionature and scale explained Chinese water governance domestically and on the Mekong River. Through combining the scale and socionature frameworks I was able to build a picture of the hybridization process creating the Chinese waterscape. Through the historical review, I showed how water has played an important part for creating political legitimacy and influencing, and being influenced, by state-led scalar projects. Because of this importance, throughout history the Chinese state has favored large state-led scalar projects for the governance of water. -

When the Navajo Generating Station Closes, Where Does the Water Go?

COLORADO NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REVIEW When the Navajo Generating Station Closes, Where Does the Water Go? Gregor Allen MacGregor* INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 291 I. HISTORICAL SETTING OF THE CURRENT CONFLICT .......................... 292 A. “Discovery” of the Colorado River; Spanish Colonization Sets the Stage for European Expansion into the Southwest ....... 292 B. American Indian Law: Sovereignty, Trust Responsibility, and Treaty Interpretation ........................................................... 293 C. Navajo Conflict and Resettlement on their Historic Homelands ............................................................................................ 295 D. Navajo Generating Station in the Context of the American Southwest’s “Big Buildup” ................................................. 297 II. OF MILLET AND MINERS: WATER LAW IN THE WEST, ON THE RESERVATIONS, AND ON THE COLORADO.................................. 301 A. Prior Appropriation: First in Time, First in Right ................ 302 B. The Winters Doctrine and the McCarran Amendment ......... 303 D. River, the Law of ................................................................. 305 1. Introduction.................................................................... 305 2. The Colorado River Compact ........................................ 306 3. Conflict in the Lower Basin Clarifies Winters .............. 307 * Mr. MacGregor is a retired US Army Cavalry Officer. This -

Those Glen Canyon Transmission Lines -- Some Facts and Figures on a Bitter Dispute

[July 1961] THOSE GLEN CANYON TRANSMISSION LINES -- SOME FACTS AND FIGURES ON A BITTER DISPUTE A Special Report by Rep. Morris K. Udall Since I came to Congress in May, my office has been flooded with more mail on one single issue than the combined total dealing with Castro, Berlin, Aid to Education, and Foreign Aid. Many writers, it soon became apparent, did not have complete or adequate information about the issues or facts involved in this dispute. The matter has now been resolved by the House of Representatives, and it occurs to me that many Arizonans might want a background paper on the facts and issues as they appeared to me. I earnestly hope that those who have criticized my stand will be willing to take a look at the other side of the story -- for it has received little attention in the Arizona press. It is always sad to see a falling out among reputable and important Arizona industrial groups. In these past months we have witnessed a fierce struggle which has divided two important segments of the Arizona electrical industry. For many years Arizona Public Service Company (APSCO) and such public or consumer-owned utilities as City of Mesa, Salt River Valley Water Users Association, the electrical districts, REA co-ops, etc. have worked harmoniously solving the electrical needs of a growing state. Since early 1961, however, APSCO has been locked in deadly combat with the other groups. Charges and counter-charges have filled the air. The largest part of my mail has directly resulted from a very large, expensive (and most effective) public relations effort by APSCO, working in close cooperation with the Arizona Republic and Phoenix Gazette. -

Mormon Flat Dam Salt River Phoenix Vicinity Maricopa County Arizona

Mormon Flat Dam Salt River HAER No. AZ- 14 Phoenix Vicinity Maricopa County Arizona PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Western Region Department of Interior San Francisco, California 94102 ( ( f ' HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Mormon Flat Dam HAER No. AZ-14 Location: Mormon Flat Dam is located on the Salt River in eastern Maricopa County, Arizona. It is approximately 50 miles east of Phoenix. UTM coordinates 25 feet northeast of the dam (in feet) are: Easting 1505701.5184; Northing 12180405.3728, Zone 12. USGS 7.5 quad Mormon Flat Dam. Date of Construction: 1923-1925. Engineer: Charles C. Cragin. Present Owner: The Salt River Project. Present Use: Mormon Flat Dam is operated by the Salt River Project for the purposes of generating hydroelectic power and for storing approximately 57,000 acre feet of water for agricultural and urban uses. Significance: Mormon Flat Dam was the first dam constructed under the Salt River Project's 1920's hydroelectic expansion program. Historian: David M. Introcaso, Corporate Information Management, Salt River Project. Mormon Flat Dam HAER No. AZ-14 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I Introduction 3 Chapter II The Need to Expand the Association's Hydroelectric Capacity . • . • • . 20 Chapter III The Construction of Mormon Flat Dam . 37 Chapter IV The Construction of Horse Mesa Dam 60 Chapter V Post-Construction: Additions to the Association's Hydroelectric Program and Modifications to Mormon Flat and Horse Mesa Dams 79 Chapter VI Conclusion . 105 Chapter VII Epilogue: Expansion Backlash, "Water Users Oust Cragin" . 114 Appendixes . 130 Bibliography 145 Mormon Flat Darn HAER No. -

Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District, Arizona Salt River Project Electric System Revenue Bonds, 2017 Series A

SUPPLEMENT DATED OCTOBER 27, 2017 TO PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED OCTOBER 23, 2017 RELATING TO $737,525,000∗ Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District, Arizona Salt River Project Electric System Revenue Bonds, 2017 Series A The information provided below supplements the Preliminary Official Statement dated October 23, 2017 (the “Preliminary Official Statement”) for the above-referenced Bonds. Capitalized terms are used as defined in the Preliminary Official Statement. The following is added as a sixth paragraph under the subheading “THE DISTRICT – Organization, Management and Employees”: SRP has an established Mandatory Retirement Age policy for the General Manager and the individuals that report directly to the General Manager. Pursuant to this policy, General Manager and CEO Mark Bonsall has announced that he will retire at the end of the current fiscal year, which ends on April 30, 2018. Both the District Board and the Association Board of Governors have approved a recommendation to commence a succession planning process for a new General Manager/CEO. Please affix this Supplement to the Preliminary Official Statement that you have in your possession and forward this Supplement to any party to whom you delivered a copy of the Official Statement. ______________________ ∗ Preliminary, subject to change. PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED OCTOBER 23, 2017 NEW ISSUE FULL BOOK-ENTRY In the opinion of Special Tax Counsel, under existing statutes and court decisions and assuming compliance with the tax covenants described herein, and the accuracy of certain representations and certifications made by the Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District, interest on the 2017 Series A Bonds is excluded from gross income of the owners thereof for federal income tax purposes under Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”). -

Assessment of Japanese and Chinese Flood Control Policies

京都大学防災研究所年報 第 53 号 B 平成 22 年 6 月 Annuals of Disas. Prev. Res. Inst., Kyoto Univ., No. 53 B, 2010 Assessment of Japanese and Chinese Flood Control Policies Pingping LUO*, Yousuke YAMASHIKI, Kaoru TAKARA, Daniel NOVER**, and Bin HE * Graduate School of Engineering ,Kyoto University, Japan ** University of California, Davis, USA Synopsis The flood is one of the world’s most dangerous natural disasters that cause immense damage and accounts for a large number of deaths and damage world-wide. Good flood control policies play an extremely important role in preventing frequent floods. It is well known that China has more than 5000 years history and flood control policies and measure have been conducted since the time of Yu the great and his father’s reign. Japan’s culture is similar to China’s but took different approaches to flood control. Under the high speed development of civil engineering technology after 1660, flood control was achieved primarily through the construction of dams, dykes and other structures. However, these structures never fully stopped floods from occurring. In this research, we present an overview of flood control policies, assess the benefit of the different policies, and contribute to a better understanding of flood control. Keywords: Flood control, Dujiangyan, History, Irrigation, Land use 1. Introduction Warring States Period of China by the Kingdom of Qin. It is located in the Min River in Sichuan Floods are frequent and devastating events Province, China, near the capital Chengdu. It is still worldwide. The Asian continent is much affected in use today and still irrigates over 5,300 square by floods, particularly in China, India and kilometers of land in the region. -

Southeast Asia.Pdf

Standards SS7G9 The student will locate selected features in Southern and Eastern Asia. a. Locate on a world and regional political-physical map: Ganges River, Huang He (Yellow River), Indus River, Mekong River, Yangtze (Chang Jiang) River, Bay of Bengal, Indian Ocean, Sea of Japan, South China Sea, Yellow Sea, Gobi Desert, Taklimakan Desert, Himalayan Mountains, and Korean Peninsula. b. Locate on a world and regional political-physical map the countries of China, India, Indonesia, Japan, North Korea, South Korea, and Vietnam. Directions: Label the following countries on the political map of Asia. • China • North Korea • India • South Korea • Indonesia • Vietnam • Japan Directions: I. Draw and label the physical features listed below on the map of Asia. • Ganges River • Mekong River • Huang He (Yellow River) • Yangtze River • Indus River • Himalayan Mountains • Taklimakan Desert • Gobi Desert II. Label the following physical features on the map of Asia. • Bay of Bengal • Yellow Sea • Color the rivers DARK BLUE. • Color all other bodies of water LIGHT • Indian Ocean BLUE (or TEAL). • Sea of Japan • Color the deserts BROWN. • Korean Peninsula • Draw triangles for mountains and color • South China Sea them GREEN. • Color the peninsula RED. Directions: I. Draw and label the physical features listed below on the map of Asia. • Ganges River • Mekong River • Huang He (Yellow River) • Yangtze River • Indus River • Himalayan Mountains • Taklimakan Desert • Gobi Desert II. Label the following physical features on the map of Asia. • Bay of Bengal • Yellow Sea • Indian Ocean • Sea of Japan • Korean Peninsula • South China Sea • The Ganges River starts in the Himalayas and flows southeast through India and Bangladesh for more than 1,500 miles to the Indian Ocean. -

Arizona Biltmore Resort &

ARIZONA BILTMORE RESORT & SPA PLANNED UNIT DEVELOPMENT Z-71-08-6 Volume 1: Existing Conditions & Master Plans July 2009 Project Team Developer: Landscape Architect Pyramid Project Management LVA Urban Design Studio, LLC Ken Hoeppner Joe Young Doug Cole 120 S. Ash Avenue One Post Office Square, Ste. 3100 Tempe, AZ 85281 Boston, MA 02109 480.994.0994 617.412.2839 Civil Engineering & Traffic: Property Manager: Kimley-Horn & Associates, INC Arizona Biltmore Resort & Spa David Morris Andrew Stegen Tove White 2400 East Missouri 7878 N. 16th Street, Ste. 300 Phoenix, AZ 85016 Phoenix, AZ 85020 602.381.7634 602.944.5500 Legal: Land Planner: Snell & Wilmer, LLP LVA Urban Design Studio, LLC Nick Wood Alan Beaudoin One Arizona Center Jon Vlaming Phoenix, AZ 85004 120 S. Ash Avenue 602.382.6000 Tempe, AZ 85281 480.994.0994 Historic Preservation: Akros Inc. Public Relations: Debbie Abele Denise Resnick & Associates Jim Coffman Denise Resnick 502 S. College Avenue, Ste 311 Jeff Janas Tempe, AZ 85281 5045 N. 12th Street, Ste 110 480.774.2902 Phoenix, AZ 85014 602.956.8834 Architect & Signs: Gensler Technical Solutions Claudia Carol Paul Smith Amy Owen Sarah Dorn 2500 Broadway, Suite 300 3875 N. 44th Street, Ste 300 Santa Monica, CA 90404 Phoenix, AZ 85018 310.449.5600 602.957.3434 Lighting: Lighting Design Collaborative Landscape Architect/Master Plans John Sarkioglu EDSA Gary Garofalo Stephen Poe 1216 Arch St. 1520-A Cloverfield Blvd. Philadelphia, PA 19107 Santa Monica, CA 90404 215.569.2115 310.435.8853 July 2009 ARIZONA BILTMORE RESORT AND SPA Planned Unit Development Volume I: Existing Conditions & Master Plans Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ -

Chapter 2 Research Sections

Part I Waterway, as a great cultural landscape Chapter 2 Research Sections 2.1 Introduction The waterway was frequently renamed by people in the history of China, this is to better describe its complex contents, multi-values of the great canal. In this chapter it will introduce the study area follow the nominations of this great canal, it was renamed in thousands of years, were not only -25- showing appellation but more about the narrative space of territory and identity, also the evnormous influence in cities' lives. Grand Canal was a very large water corridor system in the territories which included the natural rivers and artificial canals. This water system could reflect various scales of the cultural landscapes. Figure 2-1 A traditional water and ink painting by Yang Chang Xu: Moon light in Han Gou water channel. In this 18th century old painting, the artist described the scenery in one section of Han water channel where was a So this chapter intends to summarize a diachronic waterway built two thousand years ago. After a busy day, boatmen have moored their ships close to the shore before study on how this waterway was developing into a nightfall, then back to the waterside residences or have a dinner in the restaurants near the waterway. The bottom right, there is an another water channel under the bridge, it implies that ship follows Han Gou water channel could recognized and identified objects from ancient China. access to other places by its urban water system. Moreover, the human geographical scientists have concluded the processes how to build the China Grand Canal, in almost 2500 years (Cheng Yu Hai, Waterway Scaling in Regional Development——— A Cultural Landscape Perspective in China Grand Canal 2008): 8th-5th BC, it firstborn and had its initial area in a macro background about growth of canals. -

Moving the River? China's South–North Water Transfer Project

Chapter 85 Moving the River? China’s South–North Water Transfer Project Darrin Magee 85.1 Introduction China is not a water-poor country. As of 1999, China’s per capita freshwater avail- ability was around 2,128 m3 (554,761 gallons) per year, more than double the internationally recognized threshold at which a country would be considered water- scarce (Gleick, 2006). The problem, however, is that there is no such thing as an average Chinese citizen in terms of access to water. More specifically, the geo- graphic and temporal disparity of China’s distribution of freshwater resources means that some parts of the country relish in (and at times, suffer from) an over-abundance of freshwater, whereas other parts of the country are haunted by the specters of draught and desertification, to say nothing of declining water quality. The example of China’s Yellow River (Huang He) has become common knowledge. The Yellow takes its name from the color of the glacial till (loess) soil through which it flows for much of its 5,464 km (3,395 mi) journey (National Bureau of Statistics, 2007). After first failing to reach the sea for a period during 1972, it then suffered similar dry-out periods for a portion of the year in 22 of the subsequent 28 years (Ju, 2000). The river so important for nurturing the earliest kingdoms that came to comprise China, once known as “China’s sorrow” because of its devastating floods, now has become a victim of over-abstraction, pollution, and desert encroachment, and a symbol of the fragility of the human-environment relationship on which our societies depend.