The Sheer Size of Irrigation Use in Northern China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World's Major Rivers

WWWWWWoorrlldd’’ss mmaajjoorr rriivveerrss AAnn IInnttrroodduuccttiioonn ttoo iinntteerrnnaattiioonnaall wwwwwwaatteerr llaawwwwww wwwwwwiitthh ccaassee ssttuuddiieess THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK WWWWWWoorrlldd’’ss mmaajjoorr rriivveerrss An introduction to international water law with case studies Colorado River Commission of Nevada 555 E. Washington Avenue, Suite 3100 Las Vegas, Nevada 89101 Phone: (702) 486-2670 Website: http://crc.nv.gov November 2008 Jacob (Jay) D. Bingham, Chairman Ace I. Robinson, Vice Chairman Andrea Anderson, Commissioner Marybel Batjer, Commissioner Chip Maxfield, Commissioner George F. Ogilvie III, Commissioner Lois Tarkanian, Commissioner George M. Caan, Executive Director Primary Author: Daniel Seligman, Attorney at Law Columbia Research Corp. P.O. Box 99249 Seattle, Washington 98139 (206) 285-1185 Project Editors: McClain Peterson, Project Manager Manager, Natural Resource Division Colorado River Commission of Nevada Sara Price Special Counsel-Consultant Colorado River Commission of Nevada Esther Valle Natural Resource Analyst Colorado River Commission of Nevada Nicole Everett Natural Resource Analyst Colorado River Commission of Nevada THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK World’s Major Rivers ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Daniel Seligman at the Columbia Research Corp. wishes to thank Jacqueline Pruner, attorney at law in Seattle, for her contribution to the section on water law in Canada and her valuable editing assistance throughout the entire document. The staff at the Murray-Darling Basin Commission and Goulburn-Murray Water in Australia provided important information about the Murray-Darling River system, patiently answered the author’s questions, and reviewed the draft text on water trading. Staff at the International Joint Commission in Washington, D.C., and the Prairie Provinces Water Board in Regina, Canada, also offered helpful comments on an earlier draft. -

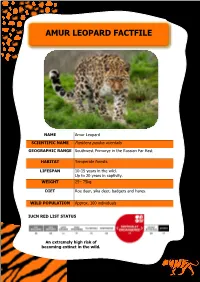

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

Dams on the Mekong

Dams on the Mekong A literature review of the politics of water governance influencing the Mekong River Karl-Inge Olufsen Spring 2020 Master thesis in Human geography at the Department of Sociology and Human Geography, Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Words: 28,896 08.07.2020 II Dams on the Mekong A literature review of the politics of water governance influencing the Mekong River III © Karl-Inge Olufsen 2020 Dams on the Mekong: A literature review of the politics of water governance influencing the Mekong River Karl-Inge Olufsen http://www.duo.uio.no/ IV Summary This thesis offers a literature review on the evolving human-nature relationship and effect of power struggles through political initiatives in the context of Chinese water governance domestically and on the Mekong River. The literature review covers theoretical debates on scale and socionature, combining them into one framework to understand the construction of the Chinese waterscape and how it influences international governance of the Mekong River. Purposive criterion sampling and complimentary triangulation helped me do rigorous research despite relying on secondary sources. Historical literature review and integrative literature review helped to build an analytical narrative where socionature and scale explained Chinese water governance domestically and on the Mekong River. Through combining the scale and socionature frameworks I was able to build a picture of the hybridization process creating the Chinese waterscape. Through the historical review, I showed how water has played an important part for creating political legitimacy and influencing, and being influenced, by state-led scalar projects. Because of this importance, throughout history the Chinese state has favored large state-led scalar projects for the governance of water. -

Amur Oblast TYNDINSKY 361,900 Sq

AMUR 196 Ⅲ THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST SAKHA Map 5.1 Ust-Nyukzha Amur Oblast TY NDINS KY 361,900 sq. km Lopcha Lapri Ust-Urkima Baikal-Amur Mainline Tynda CHITA !. ZEISKY Kirovsky Kirovsky Zeiskoe Zolotaya Gora Reservoir Takhtamygda Solovyovsk Urkan Urusha !Skovorodino KHABAROVSK Erofei Pavlovich Never SKOVO MAGDAGACHINSKY Tra ns-Siberian Railroad DIRO Taldan Mokhe NSKY Zeya .! Ignashino Ivanovka Dzhalinda Ovsyanka ! Pioner Magdagachi Beketovo Yasny Tolbuzino Yubileiny Tokur Ekimchan Tygda Inzhan Oktyabrskiy Lukachek Zlatoustovsk Koboldo Ushumun Stoiba Ivanovskoe Chernyaevo Sivaki Ogodzha Ust-Tygda Selemdzhinsk Kuznetsovo Byssa Fevralsk KY Kukhterin-Lug NS Mukhino Tu Novorossiika Norsk M DHI Chagoyan Maisky SELE Novovoskresenovka SKY N OV ! Shimanovsk Uglovoe MAZ SHIMA ANOV Novogeorgievka Y Novokievsky Uval SK EN SK Mazanovo Y SVOBODN Chernigovka !. Svobodny Margaritovka e CHINA Kostyukovka inlin SERYSHEVSKY ! Seryshevo Belogorsk ROMNENSKY rMa Bolshaya Sazanka !. Shiroky Log - Amu BELOGORSKY Pridorozhnoe BLAGOVESHCHENSKY Romny Baikal Pozdeevka Berezovka Novotroitskoe IVANOVSKY Ekaterinoslavka Y Cheugda Ivanovka Talakan BRSKY SKY P! O KTYA INSK EI BLAGOVESHCHENSK Tambovka ZavitinskIT BUR ! Bakhirevo ZAV T A M B OVSKY Muravyovka Raichikhinsk ! ! VKONSTANTINO SKY Poyarkovo Progress ARKHARINSKY Konstantinovka Arkhara ! Gribovka M LIKHAI O VSKY ¯ Kundur Innokentevka Leninskoe km A m Trans -Siberianad Railro u 100 r R i v JAO Russian Far East e r By Newell and Zhou / Sources: Ministry of Natural Resources, 2002; ESRI, 2002. Newell, J. 2004. The Russian Far East: A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development. McKinleyville, CA: Daniel & Daniel. 466 pages CHAPTER 5 Amur Oblast Location Amur Oblast, in the upper and middle Amur River basin, is 8,000 km east of Moscow by rail (or 6,500 km by air). -

Effects of Flood on DOM and Total Dissolved Iron Concentration in Amur River

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 21, EGU2019-11918, 2019 EGU General Assembly 2019 © Author(s) 2019. CC Attribution 4.0 license. Effects of Flood on DOM and Total Dissolved Iron Concentration in Amur River Baixing Yan and Jiunian Guan Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Key Laboratory of Wetland Ecology and Environment, China ([email protected]) DOM is an important indicator for freshwater quality and may complex with metals. It is already found that the water quality was abnormal during or after the flood events in various areas, which may be due to the release and resuspending of sediment in the river and leaching of the soil in the river basin area. And flood are also a major pathway for different dissolved matter, such as DOM, transport into the river system from the flood bed, wetlands, etc., when the flood was subsided. River flood has visibly impact on DOM component and concentration. The concentration and species of DOM and dissolved iron during different floods, including watershed extreme flood event, typhoon-induced flood event, snow-thawed flood event were monitored in Amur River and its biggest trib- utary Songhua River. Also, some simulation experiments in lab were implemented. The samples were filtered by 0.45µm filter membrane in situ, then analyze the ionic iron (ferrous ion, Ferric ion) by ET7406 Iron Concentration Tester(Lovibond, Germany with Phenanthroline colorimetric method). The total dissolved iron was determined by GBC 906 AAS(Australia) in lab. DOC was analyzed by TOC VCPH, SHIMADZU(Japan). The results showed that DOC ranged 6.63-9.19 mg/L (averaged at 7.68 mg/L) during extreme Songhua-Amur flood event in 2013.The lower molecular weight of organic matter[U+FF08]<10kDa[U+FF09]was the dominant form of DOM, and the lower molecular weight of complex iron was the dominant form of total dissolved iron. -

Geography – Russia

Year Six RUSSIA Key Facts • Russia (o cial name: Russian Federation) is the world’s largest • Given its size, the climate in Russia varies. The mildest areas country (with an area of 17,075, 200 square kilometres) and are along the Baltic Coast. Winter in Russia is very cold, with has a population of 144, 125, 000. The currency of Russia is the temperatures in the northern regions of Siberia reaching -50 Ruble. degrees Celsius in winter. • The capital city of Russia is Moscow. It has a population 13.2 million people within the city limits and 17 million within the Food and Trade urban areas. It is situated on the Moskva River in western Russia. • Borscht is a famous Russian soup made with beetroot and sour cream. It can be enjoyed hot or cold. Physical and Human Geographical features • St Petersburg is a major trade gateway in Russia, specialising in • Major mountain ranges: Ural, Altai. oil and gas trade, shipbuilding yards and the aerospace industry. • Major rivers: Amur, Irtysh, Lena, Ob, Volga and Yenisey. Russia The fl ag of Russian Federation (Russian: Флаг России) Geographical Skills Key Vocabulary • Children locate the world’s countries on a map, focusing on the • Map: a diagrammatic representation of an area of land showing environmental regions, key physical and human characteristics physical features, cities, roads etc. and major cities of Russia. • Symbol: something that represents or stands for something • Children further their locational knowledge through the else. accurate use of maps, atlases, globes and digital/computer • Key: information needed for a map to make sense. -

Amur (Siberian) Tiger Panthera Tigris Altaica Tiger Survival

Amur (Siberian) Tiger Panthera tigris altaica Tiger Survival - It is estimated that only 350-450 Amur (Siberian) tigers remain in the wild although there are 650 in captivity. Tigers are poached for their bones and organs, which are prized for their use in traditional medicines. A single tiger can be worth over $15,000 – more than most poor people in the region make over years. Recent conservation efforts have increased the number of wild Siberian tigers but continued efforts will be needed to ensure their survival. Can You See Me Now? - Tigers are the most boldly marked cats in the world and although they are easy to see in most zoo settings, their distinctive stripes and coloration provides the camouflage needed for a large predator in the wild. The pattern of stripes on a tigers face is as distinctive as human fingerprints – no two tigers have exactly the same stripe pattern. Classification The Amur tiger is one of 9 subspecies of tiger. Three of the 9 subspecies are extinct, and the rest are listed as endangered or critically endangered by the IUCN. Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Panthera Species: tigris Subspecies: altaica Distribution The tiger’s traditional range is through southeastern Siberia, northeast China, the Russian Far East, and northern regions of North Korea. Habitat Snow-covered deciduous, coniferous and scrub forests in the mountains. Physical Description • Males are 9-12 feet (2.7-3.6 m) long including a two to three foot (60-90 cm) tail; females are up to 9 feet (2.7 m) long. -

Taking Stock of Integrated River Basin Management in China Wang Yi, Li

Taking Stock of Integrated River Basin Management in China Wang Yi, Li Lifeng Wang Xuejun, Yu Xiubo, Wang Yahua SCIENCE PRESS Beijing, China 2007 ISBN 978-7-03-020439-4 Acknowledgements Implementing integrated river basin management (IRBM) requires complex and systematic efforts over the long term. Although experts, scientists and officials, with backgrounds in different disciplines and working at various national or local levels, are in broad agreement concerning IRBM, many constraints on its implementation remain, particularly in China - a country with thousands of years of water management history, now developing at great pace and faced with a severe water crisis. Successful implementation demands good coordination among various stakeholders and their active and innovative participation. The problems confronted in the general advance of IRBM also pose great challenges to this particular project. Certainly, the successes during implementation of the project subsequent to its launch on 11 April 2007, and the finalization of a series of research reports on The Taking Stockof IRBM in China would not have been possible without the combined efforts and fruitful collaboration of all involved. We wish to express our heartfelt gratitude to each and every one of them. We should first thank Professor and President Chen Yiyu of the National Natural Science Foundation of China, who gave his valuable time and shared valuable knowledge when chairing the work meeting which set out guidelines for research objectives, and also during discussions of the main conclusions of the report. It is with his leadership and kind support that this project came to a successful conclusion. We are grateful to Professor Fu Bojie, Dr. -

The Threatened and Near-Threatened Birds of Northern Ussuriland, South-East Russia, and the Role of the Bikin River Basin in Their Conservation KONSTANTIN E

Bird Conservation International (1998) 8:141-171. © BirdLife International 1998 The threatened and near-threatened birds of northern Ussuriland, south-east Russia, and the role of the Bikin River basin in their conservation KONSTANTIN E. MIKHAILOV and YURY B. SHIBNEV Summary Fieldwork on the distribution, habitat preferences and status of birds was conducted in the Bikin River basin, northern Ussuriland, south-east Russia, during May-July 1992,1993, 1995,1996 and 1997. The results of this survey combined with data collected during 1960- 1990, show the area to be of high conservation priority and one of the most important for the conservation of Blakiston's Fish Owl Ketupa blakistoni, Chinese Merganser Mergus squamatus, Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata and Hooded Crane Grus monacha. This paper reports on all of the 13 threatened and near-threatened breeding species of northern Ussuriland, with special emphasis on their occurrence and status in the Bikin area. Three more species, included in the Red Data Book of Russia, are also briefly discussed. Maps show the distribution of the breeding sites of the species discussed. The establishment of a nature reserve in the lower Bikin area is suggested as the only way to conserve the virgin Manchurian-type habitats (wetlands and forests), and all 10 species of special conservation concern. Monitoring of the local populations of Blakiston's Fish Owl, Chinese Merganser and Mandarin Duck in the middle Bikin is required. Introduction No other geographical region of Russia has as rich a biodiversity as Ussuriland which includes the territory of Primorski Administrative Region and the most southern part of Khabarovsk Administrative Region. -

Assessment of Japanese and Chinese Flood Control Policies

京都大学防災研究所年報 第 53 号 B 平成 22 年 6 月 Annuals of Disas. Prev. Res. Inst., Kyoto Univ., No. 53 B, 2010 Assessment of Japanese and Chinese Flood Control Policies Pingping LUO*, Yousuke YAMASHIKI, Kaoru TAKARA, Daniel NOVER**, and Bin HE * Graduate School of Engineering ,Kyoto University, Japan ** University of California, Davis, USA Synopsis The flood is one of the world’s most dangerous natural disasters that cause immense damage and accounts for a large number of deaths and damage world-wide. Good flood control policies play an extremely important role in preventing frequent floods. It is well known that China has more than 5000 years history and flood control policies and measure have been conducted since the time of Yu the great and his father’s reign. Japan’s culture is similar to China’s but took different approaches to flood control. Under the high speed development of civil engineering technology after 1660, flood control was achieved primarily through the construction of dams, dykes and other structures. However, these structures never fully stopped floods from occurring. In this research, we present an overview of flood control policies, assess the benefit of the different policies, and contribute to a better understanding of flood control. Keywords: Flood control, Dujiangyan, History, Irrigation, Land use 1. Introduction Warring States Period of China by the Kingdom of Qin. It is located in the Min River in Sichuan Floods are frequent and devastating events Province, China, near the capital Chengdu. It is still worldwide. The Asian continent is much affected in use today and still irrigates over 5,300 square by floods, particularly in China, India and kilometers of land in the region. -

Southeast Asia.Pdf

Standards SS7G9 The student will locate selected features in Southern and Eastern Asia. a. Locate on a world and regional political-physical map: Ganges River, Huang He (Yellow River), Indus River, Mekong River, Yangtze (Chang Jiang) River, Bay of Bengal, Indian Ocean, Sea of Japan, South China Sea, Yellow Sea, Gobi Desert, Taklimakan Desert, Himalayan Mountains, and Korean Peninsula. b. Locate on a world and regional political-physical map the countries of China, India, Indonesia, Japan, North Korea, South Korea, and Vietnam. Directions: Label the following countries on the political map of Asia. • China • North Korea • India • South Korea • Indonesia • Vietnam • Japan Directions: I. Draw and label the physical features listed below on the map of Asia. • Ganges River • Mekong River • Huang He (Yellow River) • Yangtze River • Indus River • Himalayan Mountains • Taklimakan Desert • Gobi Desert II. Label the following physical features on the map of Asia. • Bay of Bengal • Yellow Sea • Color the rivers DARK BLUE. • Color all other bodies of water LIGHT • Indian Ocean BLUE (or TEAL). • Sea of Japan • Color the deserts BROWN. • Korean Peninsula • Draw triangles for mountains and color • South China Sea them GREEN. • Color the peninsula RED. Directions: I. Draw and label the physical features listed below on the map of Asia. • Ganges River • Mekong River • Huang He (Yellow River) • Yangtze River • Indus River • Himalayan Mountains • Taklimakan Desert • Gobi Desert II. Label the following physical features on the map of Asia. • Bay of Bengal • Yellow Sea • Indian Ocean • Sea of Japan • Korean Peninsula • South China Sea • The Ganges River starts in the Himalayas and flows southeast through India and Bangladesh for more than 1,500 miles to the Indian Ocean. -

Sino-Russian Transboundary Waters: a Legal Perspective on Cooperation

Sino---Russian-Russian Transboundary Waters: A Legal Perspective on Cooperation Sergei Vinogradov Patricia Wouters STOCKHOLM PAPER December 2013 Sino-Russian Transboundary Waters: A Legal Perspective on Cooperation Sergei Vinogradov Patricia Wouters Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu Sino-Russian Transboundary Waters: A Legal Perspective on Cooperation is a Stockholm Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Stockholm Papers Series is an Occasional Paper series addressing topical and timely issues in international affairs. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publica- tions, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a fo- cal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. The opinions and conclusions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute for Security and Development Pol- icy or its sponsors. © Institute for Security and Development Policy, 2013 ISBN: 978-91-86635-71-8 Cover photo: The Argun River running along the Chinese and Russian border, http://tupian.baike.com/a4_50_25_01200000000481120167252214222_jpg.html Printed in Singapore Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. +46-841056953; Fax. +46-86403370 Email: [email protected] Distributed in North America by: The Central Asia-Caucasus Institute Paul H.