Amur Fish: Wealth and Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Analytical Digest No 7: Migration

No. 7 3 October 2006 rrussianussian aanalyticalnalytical ddigestigest www.res.ethz.ch www.russlandanalysen.de MIGRATION ■ ANALYSIS Immigration and Russian Migration Policy: Debating the Future. Vladimir Mukomel, Moscow 2 ■ TABLES AND DIAGRAMS Migration and Racism 6 ■ REGIONAL REPORT Ethnic Russians Flee the North Caucasus. Oleg Tsvetkov, Maikop 9 ■ REGIONAL REPORT Authorities Hope Chinese Investment Will Bring Russians Back to Far East. Oleg Ssylka, Vladivostok 13 Research Centre for East CSS Center for Security Otto Wolff -Stiftung DGO European Studies, Bremen An ETH Center Studies, ETH Zurich rrussianussian aanalyticalnalytical russian analytical digest 07/06 ddigestigest Analysis Immigration and Russian Migration Policy: Debating the Future By Vladimir Mukomel, Center for Ethno-Political and Regional Studies, Moscow Summary While war refugees and returnees dominated immigration to Russia during the 1990s, in recent years, most immigrants are laborers who want to benefi t from the Russian economic upturn. Th ese immigrants face ex- tremely poor working conditions and they are socially ostracized by the vast majority of the Russian popula- tion. At the same time, immigration could prove to be the solution to the country’s demographic problems, countering the decline of its working population. So far, Russian migration policy has not formulated a convincing response to this dilemma. Introduction about one million immigrants returned to Russia an- he façade of heated political debates over per- nually from the CIS states and the Baltic republics. Tspectives for immigration and migration policy Most of the immigrants who resettled in Russia after disguises a clash of views over the future of Russia. the dissolution of the USSR arrived during this period Th e advocates of immigration – liberals and pragma- (see Fig. -

Teleostei: Cyprinidae: Acheilognathinae) from China

Zootaxa 3790 (1): 165–176 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3790.1.7 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:BD573A51-6656-4E86-87C2-2411443C38E5 Rhodeus albomarginatus, a new bitterling (Teleostei: Cyprinidae: Acheilognathinae) from China FAN LI1,3 & RYOICHI ARAI2 1Institute of Biodiversity Science, Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Biodiversity Science and Ecological Engineering, Fudan University, Shanghai 200433, China. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Zoology, University Museum, University of Tokyo, 7–3–1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo. 113-0033, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] 3Corresponding author Abstract Rhodeus albomarginatus, new species, is described from the Lvjiang River, a tributary flowing into Poyang Lake of Yang- tze River basin, in Anhui Province, China. It is distinguished from all congeneric species by unique combination of char- acters: branched dorsal-fin rays 10; branched anal-fin rays 10–11; longest simple rays of dorsal and anal fins strong and stiff, distally segmented; pelvic fin rays i 6; longitudinal scale series 34–36; transverse scale series 11; pored scales 4–7; vertebrae 33–34; colour pattern of adult males (iris black, belly reddish-orange, central part of caudal fin red, dorsal and anal fins of males edged with white margin). Key words: Cyprinidae, Rhodeus albomarginatus, new species, Yangtze River, China Introduction Bitterling belong to the subfamily Acheilognathinae in Cyprinidae and include three genera, Acheilognathus, Rhodeus and Tanakia. The genus Rhodeus can be distinguished from the other two genera by having an incomplete lateral line, no barbels, and wing-like yolk sac projections in larvae (Arai & Akai, 1988). -

The Intermediate Performance of Territories of Priority Socio-Economic Development in Russia in Conditions of Macroeconomic Instability

MATEC Web of Conferences 106, 01028 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201710601028 SPbWOSCE-2016 The intermediate performance of territories of priority socio-economic development in Russia in conditions of macroeconomic instability Sergey Beliakov1,*, Anna Kapustkina1 1Moscow state university of civil engineering, YaroslavskoyeShosse, 26, Moscow, 12933, Russia Abstract. The Russian economy in recent years has faced the influence of a number of negative factors due to macroeconomic instability and increased foreign policy tensions. In these conditions the considerable constraints faced processes of socio-economic development of regions of the Russian Federation. In this article the authors attempt to analyze the key indicators of socio-economic development of the regions in which it was created and operate in the territories of priority socio-economic development. These territories are concentrated in the Far Eastern Federal District. The article identified, processed, and interpreted indicators, allowing to produce a conclusion on the interim effectiveness of the territories of priority socio-economic development in Russia in conditions of macroeconomic instability. 1 Introduction The main purpose of socio-economic policy is to increase the standard of living, increasing prosperity and ensuring social guarantees to the population. Without these indicators, it is impossible to imagine the effective development of civil society and of the economy as a whole. The crisis in macroeconomics and world politics led to the deterioration of the General economic situation in Russia and, as consequence, decrease in level of living of the population [1, 2]. 2 Experimental section Statistics show that in most Russian regions indicators of the level of living of the population significantly differ from similar indicators in the regional centers. -

Review and Meta-Analysis of the Environmental Biology and Potential Invasiveness of a Poorly-Studied Cyprinid, the Ide Leuciscus Idus

REVIEWS IN FISHERIES SCIENCE & AQUACULTURE https://doi.org/10.1080/23308249.2020.1822280 REVIEW Review and Meta-Analysis of the Environmental Biology and Potential Invasiveness of a Poorly-Studied Cyprinid, the Ide Leuciscus idus Mehis Rohtlaa,b, Lorenzo Vilizzic, Vladimır Kovacd, David Almeidae, Bernice Brewsterf, J. Robert Brittong, Łukasz Głowackic, Michael J. Godardh,i, Ruth Kirkf, Sarah Nienhuisj, Karin H. Olssonh,k, Jan Simonsenl, Michał E. Skora m, Saulius Stakenas_ n, Ali Serhan Tarkanc,o, Nildeniz Topo, Hugo Verreyckenp, Grzegorz ZieRbac, and Gordon H. Coppc,h,q aEstonian Marine Institute, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia; bInstitute of Marine Research, Austevoll Research Station, Storebø, Norway; cDepartment of Ecology and Vertebrate Zoology, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz, Łod z, Poland; dDepartment of Ecology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Comenius University, Bratislava, Slovakia; eDepartment of Basic Medical Sciences, USP-CEU University, Madrid, Spain; fMolecular Parasitology Laboratory, School of Life Sciences, Pharmacy and Chemistry, Kingston University, Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey, UK; gDepartment of Life and Environmental Sciences, Bournemouth University, Dorset, UK; hCentre for Environment, Fisheries & Aquaculture Science, Lowestoft, Suffolk, UK; iAECOM, Kitchener, Ontario, Canada; jOntario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada; kDepartment of Zoology, Tel Aviv University and Inter-University Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat, Tel Aviv, -

Analysis of Genetic Diversity of Leuciscus Leuciscus Baicalensis Using Novel Microsatellite Markers with Cross-Species Transferability

Analysis of genetic diversity of Leuciscus leuciscus baicalensis using novel microsatellite markers with cross-species transferability D.J. Lei1, G. Zhao1, P. Xie1, Y. Li1, H. Yuan1, M. Zou1, J.G. Niu2 and X.F. Ma1 1College of Fisheries, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, China 2Xinjiang Fisheries Research Institute, Urumqi, China Corresponding author: X.F. Ma E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 16 (2): gmr16029376 Received September 23, 2016 Accepted March 8, 2017 Published May 4, 2017 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/gmr16029376 Copyright © 2017 The Authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike (CC BY-SA) 4.0 License. ABSTRACT. We used next-generation sequencing technology to characterize 19 genomic simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers and 11 expressed sequence tag (EST) SSR markers from Leuciscus leuciscus baicalensis, a small freshwater fish that is widely distributed in Xinjiang, China. Primers were used to test for polymorphisms in three L. leuciscus baicalensis populations in Xinjiang. There were 4-27 (average 11.3) alleles (NA), the expected heterozygosity (HE) was 0.36-0.94 (average 0.75 ± 0.14), the observed heterozygosity (HO) was 0.37-1.00 (average 0.68 ± 0.18), and the polymorphism information content (PIC) was 0.31-0.93 (average 0.71). The averages of HE and PIC for the EST-SSR markers were slightly lower than for the genomic SSR markers. Genetic analysis of the three populations showed similar results for PIC, HE, and NA. Amplifications were performed in nine other species; the top three transferability values were for Rutilus lacustris (80%), Leuciscus idus (76.7%), and Phoxinus ujmonensis (63.3%), with the following average values: PIC (0.56, 4.46, and 0.52); NA (0.40, 3.00, and 0.32); and HO (0.44, 2.74, and 0.22), respectively. -

Cretaceous Deposits and Flora of the Muravyov Amurskii Peninsula

ISSN 08695938, Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation, 2015, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 281–299. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2015. Original Russian Text © E.B. Volynets, 2015, published in Stratigrafiya. Geologicheskaya Korrelyatsiya, 2015, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 50–68. Cretaceous Deposits and Flora of the MuravyovAmurskii Peninsula (Amur Bay, Sea of Japan) E. B. Volynets Institute of Biology and Soil Science, Far East Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, pr. 100letiya Vladivostoka 159, Vladivostok, 690022 Russia email: [email protected] Received August 21, 2013; in final form, March 24, 2014 Abstract—The Cretaceous sections and plant macrofossils are investigated in detail near Vladivostok on the MuravyovAmurskii Peninsula of southern Primorye. It is established that the Ussuri and Lipovtsy forma tions in the reference section of the Markovskii Peninsula rest with unconformity upon Upper Triassic strata. The continuous Cretaceous succession is revealed in the Peschanka River area of the northern Muravyov Amurskii Peninsula, where plant remains were first sampled from the lower and upper parts of the Korkino Group, which are determined to be the late Albian–late Cenmanian in age. The taxonomic composition of floral assemblages from the Ussuri, Lipovtsy, and Galenki formations is widened owing to additional finds of plant remains. The Korkino Group received floral characteristics for the first time. The Cretaceous flora of the peninsula is represented by 126 taxa. It is established that ferns and conifers are dominant elements of the Ussuri floral assemblage, while the Lipovtsy Assemblage is dominated by ferns, conifers, and cycadphytes. In addition, the latter assemblage is characterized by the highest taxonomic diversity. The Galenki Assemblage is marked by the first appearance of rare flowering plants against the background of dominant ferns and coni fers. -

Russia) Biodiversity

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at SCHLOTGAUER • Anthropogenic changes of Priamurje biodiversity STAPFIA 95 (2011): 28–32 Anthropogenic Changes of Priamurje (Russia) Biodiversity S.D. SCHLOTGAUER* Abstract: The retrospective analysis is focused on anthropogenic factors, which have formed modern biodiversity and caused crucial ecological problems in Priamurje. Zusammenfassung: Eine retrospektive Analyse anthropogener Faktoren auf die Biodiversität und die ökologischen Probleme der Region Priamurje (Russland) wird vorgestellt . Key words: Priamurje, ecological functions of forests, ecosystem degradation, forest resource use, bioindicators, rare species, agro-landscapes. * Correspondence to: [email protected] Introduction Our research was focused on revealing current conditions of the vegetation cover affected by fires and timber felling. Compared to other Russian Far Eastern territories the Amur Basin occupies not only the vastest area but also has a unique geographical position as being a contact zone of the Circum- Methods boreal and East-Asian areas, the two largest botanical-geograph- ical areas on our planet. Such contact zones usually contain pe- The field research was undertaken in three natural-historical ripheral areals of many plants as a complex mosaic of ecological fratries: coniferous-broad-leaved forests, spruce and fir forests conditions allows floristic complexes of different origin to find and larch forests. The monitoring was carried out at permanent a suitable habitat. and temporary sites in the Amur valley, in the valleys of the The analysis of plant biodiversity dynamics seems necessary Amur biggest tributaries (the Amgun, Anui, Khor, Bikin, Bira, as the state of biodiversity determines regional population health Bureyza rivers) and in such divines as the Sikhote-Alin, Myao and welfare. -

Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis of Wild Amur Ide (Leuciscus Waleckii) Inhabiting an Extreme Alkaline-Saline Lake Reveals Insights Into Stress Adaptation

Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis of Wild Amur Ide (Leuciscus waleckii) Inhabiting an Extreme Alkaline- Saline Lake Reveals Insights into Stress Adaptation Jian Xu1, Peifeng Ji1, Baosen Wang1,2, Lan Zhao1, Jian Wang1, Zixia Zhao1, Yan Zhang1, Jiongtang Li1, Peng Xu1*, Xiaowen Sun1* 1 Centre for Applied Aquatic Genomics, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Beijing, China, 2 College of Life Sciences, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China Abstract Background: Amur ide (Leuciscus waleckii) is an economically and ecologically important species in Northern Asia. The Dali Nor population inhabiting Dali Nor Lake, a typical saline-alkaline lake in Inner Mongolia, is well-known for its adaptation to extremely high alkalinity. Genome information is needed for conservation and aquaculture purposes, as well as to gain further understanding into the genetics of stress tolerance. The objective of the study is to sequence the transcriptome and obtain a well-assembled transcriptome of Amur ide. Results: The transcriptome of Amur ide was sequenced using the Illumina platform and assembled into 53,632 cDNA contigs, with an average length of 647 bp and a N50 length of 1,094 bp. A total of 19,338 unique proteins were identified, and gene ontology and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) analyses classified all contigs into functional categories. Open Reading Frames (ORFs) were detected from 34,888 (65.1%) of contigs with an average length of 577 bp, while 9,638 full-length cDNAs were identified. Comparative analyses revealed that 31,790 (59.3%) contigs have a significant similarity to zebrafish proteins, and 27,096 (50.5%), 27,524 (51.3%) and 27,996 (52.2%) to teraodon, medaka and three- spined stickleback proteins, respectively. -

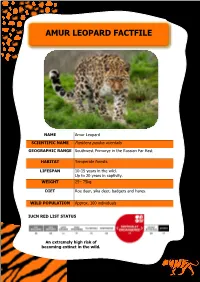

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

Esox Lucius) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Northern Pike (Esox lucius) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, February 2019 Web Version, 8/26/2019 Photo: Ryan Hagerty/USFWS. Public Domain – Government Work. Available: https://digitalmedia.fws.gov/digital/collection/natdiglib/id/26990/rec/22. (February 1, 2019). 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Froese and Pauly (2019a): “Circumpolar in fresh water. North America: Atlantic, Arctic, Pacific, Great Lakes, and Mississippi River basins from Labrador to Alaska and south to Pennsylvania and Nebraska, USA [Page and Burr 2011]. Eurasia: Caspian, Black, Baltic, White, Barents, Arctic, North and Aral Seas and Atlantic basins, southwest to Adour drainage; Mediterranean basin in Rhône drainage and northern Italy. Widely distributed in central Asia and Siberia easward [sic] to Anadyr drainage (Bering Sea basin). Historically absent from Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean France, central Italy, southern and western Greece, eastern Adriatic basin, Iceland, western Norway and northern Scotland.” Froese and Pauly (2019a) list Esox lucius as native in Armenia, Azerbaijan, China, Georgia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Moldova, Monaco, 1 Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Ukraine, Canada, and the United States (including Alaska). From Froese and Pauly (2019a): “Occurs in Erqishi river and Ulungur lake [in China].” “Known from the Selenge drainage [in Mongolia] [Kottelat 2006].” “[In Turkey:] Known from the European Black Sea watersheds, Anatolian Black Sea watersheds, Central and Western Anatolian lake watersheds, and Gulf watersheds (Firat Nehri, Dicle Nehri). -

The European Fortifications on the Coast of the Pacific Ocean

Scientific Journal of Latvia University of Agriculture Landscape Architecture and Art, Volume 10, Number 10 The European fortifications on the coast of the Pacific Ocean Nikolay Kasyanov, Research Institute of Theory and History of Architecture and Urban Planning of the Russian Academy of Architecture and Construction Sciences, Moscow, Russia Abstract. In the Russian Empire during XIX and early XX centuries, fortresses were built and strengthened along the frontiers. We studied the architecture of the Far Eastern Russian cities-fortresses using as examples Nikolaevsk-on-Amur, Port Arthur (now Luishun) and mainly Vladivostok. Coastal fortresses significantly influenced the urban development of the Far Eastern cities. The architectural peculiarity of the fortress architecture at that period was associated with the transition from the brick and stone fortifications to the complex systems of monolithic reinforced concrete. In 1860, a military post with the expressive and geopolitically ambitious name "Vladivostok" ("Possess the East") was established. By the beginning of the XX century, Vladivostok became a rapidly growing city of the European culture and one of the most powerful marine fortresses in the world. The Vladivostok Fortress was an innovative project in early XX century and has distinctive features of the modern style (Art Nouveau), partly of the Russian and classical style in architecture, as well as an organic unity with the surrounding landscape. Plastic architectural masses with their non-linear shape are typical of the fortifications of Vladivostok. Vast and branching internal communication spaces link fort buildings, scattered on the surface and remote from each other. Huge, monumental forts located on the tops of mountains and fitted perfectly in the landscape are successful examples of landscape architecture. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................