Russian Analytical Digest No 7: Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of Exporters of Primorsky Krai № ITN/TIN Company Name Address OKVED Code Kind of Activity Country of Export 1 254308

Catalogue of exporters of Primorsky krai № ITN/TIN Company name Address OKVED Code Kind of activity Country of export 690002, Primorsky KRAI, 1 2543082433 KOR GROUP LLC CITY VLADIVOSTOK, PR-T OKVED:51.38 Wholesale of other food products Vietnam OSTRYAKOVA 5G, OF. 94 690001, PRIMORSKY KRAI, 2 2536266550 LLC "SEIKO" VLADIVOSTOK, STR. OKVED:51.7 Other ratailing China TUNGUS, 17, K.1 690003, PRIMORSKY KRAI, VLADIVOSTOK, 3 2531010610 LLC "FORTUNA" OKVED: 46.9 Wholesale trade in specialized stores China STREET UPPERPORTOVA, 38- 101 690003, Primorsky Krai, Vladivostok, Other activities auxiliary related to 4 2540172745 TEK ALVADIS LLC OKVED: 52.29 Panama Verkhneportovaya street, 38, office transportation 301 p-303 p 690088, PRIMORSKY KRAI, Wholesale trade of cars and light 5 2537074970 AVTOTRADING LLC Vladivostok, Zhigura, 46 OKVED: 45.11.1 USA motor vehicles 9KV JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 690091, Primorsky KRAI, Processing and preserving of fish and 6 2504001293 HOLDING COMPANY " Vladivostok, Pologaya Street, 53, OKVED:15.2 China seafood DALMOREPRODUKT " office 308 JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 692760, Primorsky Krai, Non-scheduled air freight 7 2502018358 OKVED:62.20.2 Moldova "AVIALIFT VLADIVOSTOK" CITYARTEM, MKR-N ORBIT, 4 transport 690039, PRIMORSKY KRAI JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 8 2543127290 VLADIVOSTOK, 16A-19 KIROV OKVED:27.42 Aluminum production Japan "ANKUVER" STR. 692760, EDGE OF PRIMORSKY Activities of catering establishments KRAI, for other types of catering JOINT-STOCK COMPANY CITYARTEM, STR. VLADIMIR 9 2502040579 "AEROMAR-ДВ" SAIBEL, 41 OKVED:56.29 China Production of bread and pastry, cakes 690014, Primorsky Krai, and pastries short-term storage JOINT-STOCK COMPANY VLADIVOSTOK, STR. PEOPLE 10 2504001550 "VLADHLEB" AVENUE 29 OKVED:10.71 China JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " MINING- METALLURGICAL 692446, PRIMORSKY KRAI COMPLEX DALNEGORSK AVENUE 50 Mining and processing of lead-zinc 11 2505008358 " DALPOLIMETALL " SUMMER OCTOBER 93 OKVED:07.29.5 ore Republic of Korea 692183, PRIMORSKY KRAI KRAI, KRASNOARMEYSKIY DISTRICT, JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " P. -

The Intermediate Performance of Territories of Priority Socio-Economic Development in Russia in Conditions of Macroeconomic Instability

MATEC Web of Conferences 106, 01028 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201710601028 SPbWOSCE-2016 The intermediate performance of territories of priority socio-economic development in Russia in conditions of macroeconomic instability Sergey Beliakov1,*, Anna Kapustkina1 1Moscow state university of civil engineering, YaroslavskoyeShosse, 26, Moscow, 12933, Russia Abstract. The Russian economy in recent years has faced the influence of a number of negative factors due to macroeconomic instability and increased foreign policy tensions. In these conditions the considerable constraints faced processes of socio-economic development of regions of the Russian Federation. In this article the authors attempt to analyze the key indicators of socio-economic development of the regions in which it was created and operate in the territories of priority socio-economic development. These territories are concentrated in the Far Eastern Federal District. The article identified, processed, and interpreted indicators, allowing to produce a conclusion on the interim effectiveness of the territories of priority socio-economic development in Russia in conditions of macroeconomic instability. 1 Introduction The main purpose of socio-economic policy is to increase the standard of living, increasing prosperity and ensuring social guarantees to the population. Without these indicators, it is impossible to imagine the effective development of civil society and of the economy as a whole. The crisis in macroeconomics and world politics led to the deterioration of the General economic situation in Russia and, as consequence, decrease in level of living of the population [1, 2]. 2 Experimental section Statistics show that in most Russian regions indicators of the level of living of the population significantly differ from similar indicators in the regional centers. -

Russia) Biodiversity

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at SCHLOTGAUER • Anthropogenic changes of Priamurje biodiversity STAPFIA 95 (2011): 28–32 Anthropogenic Changes of Priamurje (Russia) Biodiversity S.D. SCHLOTGAUER* Abstract: The retrospective analysis is focused on anthropogenic factors, which have formed modern biodiversity and caused crucial ecological problems in Priamurje. Zusammenfassung: Eine retrospektive Analyse anthropogener Faktoren auf die Biodiversität und die ökologischen Probleme der Region Priamurje (Russland) wird vorgestellt . Key words: Priamurje, ecological functions of forests, ecosystem degradation, forest resource use, bioindicators, rare species, agro-landscapes. * Correspondence to: [email protected] Introduction Our research was focused on revealing current conditions of the vegetation cover affected by fires and timber felling. Compared to other Russian Far Eastern territories the Amur Basin occupies not only the vastest area but also has a unique geographical position as being a contact zone of the Circum- Methods boreal and East-Asian areas, the two largest botanical-geograph- ical areas on our planet. Such contact zones usually contain pe- The field research was undertaken in three natural-historical ripheral areals of many plants as a complex mosaic of ecological fratries: coniferous-broad-leaved forests, spruce and fir forests conditions allows floristic complexes of different origin to find and larch forests. The monitoring was carried out at permanent a suitable habitat. and temporary sites in the Amur valley, in the valleys of the The analysis of plant biodiversity dynamics seems necessary Amur biggest tributaries (the Amgun, Anui, Khor, Bikin, Bira, as the state of biodiversity determines regional population health Bureyza rivers) and in such divines as the Sikhote-Alin, Myao and welfare. -

Putin: Russia's Choice, Second Edition

Putin The second edition of this extremely well-received political biography of Vladimir Putin builds on the strengths of the previous edition to provide the most detailed and nuanced account of the man, his politics and his pro- found influence on Russian politics, foreign policy and society. New to this edition: Analysis of Putin’s second term as President. More biographical information in the light of recent research. Detailed discussion of changes to the policy process and the elites around Putin. Developments in state–society relations including the conflicts with oli- garchs such as Khodorkovsky. Review of changes affecting the party system and electoral legislation, including the development of federalism in Russia. Details on economic performance under Putin, including more discus- sion of the energy sector and pipeline politics. Russia’s relationship with Nato after the ‘big-bang’ enlargement, EU– Russian relations after enlargement and Russia’s relations with other post- Soviet states. The conclusion brings us up to date with debates over the question of democracy in Russia today, and the nature of Putin’s leadership and his place in the world. Putin: Russia’s choice is essential reading for all scholars and students of Russian politics. Richard Sakwa is Professor of Politics at the University of Kent, UK. Putin Russia’s choice Second edition Richard Sakwa First edition published 2004 Second edition, 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007. -

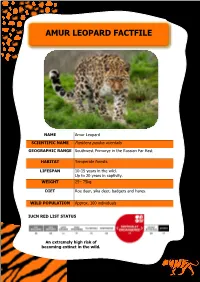

Amur Leopard Fact File

AMUR LEOPARD FACTFILE NAME Amur Leopard SCIENTIFIC NAME Panthera pardus orientalis GEOGRAPHIC RANGE Southwest Primorye in the Russian Far East HABITAT Temperate forests. LIFESPAN 10-15 years in the wild. Up to 20 years in captivity. WEIGHT 25– 75kg DIET Roe deer, sika deer, badgers and hares. WILD POPULATION Approx. 100 individuals IUCN RED LIST STATUS An extremely high risk of becoming extinct in the wild. GENERAL DESCRIPTION Amur leopards are one of nine sub-species of leopard. They are the most critically endangered big cat in the world. Found in the Russian far-east, Amur leopards are well adapted to a cold climate with thick fur that can reach up to 7.5cm long in winter months. Amur leopards are much paler than other leopards, with bigger and more spaced out rosettes. This is to allow them to camouflage in the snow. In the 20th century the Amur leopard population dramatically decreased due to habitat loss and hunting. Prior to this their range extended throughout northeast China, the Korean peninsula and the Primorsky Krai region of Russia. Now the Amur leopard range is predominantly in the south of the Primorsky Krai region in Russia, however, individuals have been reported over the border into northeast China. In 2011 Amur leopard population estimates were extremely low with approximately 35 individuals remaining. Intensified protection of this species has lead to a population increase, with approximately 100 now remaining in the wild. AMUR LEOPARD RANGE THREATS • Illegal wildlife trade– poaching for furs, teeth and bones is a huge threat to Amur leopards. A hunting culture, for both sport and food across Russia, also targets the leopards and their prey species. -

A Region with Special Needs the Russian Far East in Moscow’S Policy

65 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’s pOLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer NUMBER 65 WARSAW JUNE 2017 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’S POLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITOR Adam Eberhardt, Marek Menkiszak EDITOR Katarzyna Kazimierska CO-OPERATION Halina Kowalczyk, Anna Łabuszewska TRANSLATION Ilona Duchnowicz CO-OPERATION Timothy Harrell GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH PHOTOgrAPH ON COVER Mikhail Varentsov, Shutterstock.com DTP GroupMedia MAPS Wojciech Mańkowski PUBLISHER Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-65827-06-7 Contents THESES /5 INTRODUctiON /7 I. THE SPEciAL CHARActERISticS OF THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST AND THE EVOLUtiON OF THE CONCEPT FOR itS DEVELOPMENT /8 1. General characteristics of the Russian Far East /8 2. The Russian Far East: foreign trade /12 3. The evolution of the Russian Far East development concept /15 3.1. The Soviet period /15 3.2. The 1990s /16 3.3. The rule of Vladimir Putin /16 3.4. The Territories of Advanced Development /20 II. ENERGY AND TRANSPORT: ‘THE FLYWHEELS’ OF THE FAR EAST’S DEVELOPMENT /26 1. The energy sector /26 1.1. The resource potential /26 1.2. The infrastructure /30 2. Transport /33 2.1. Railroad transport /33 2.2. Maritime transport /34 2.3. Road transport /35 2.4. -

Amur Oblast TYNDINSKY 361,900 Sq

AMUR 196 Ⅲ THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST SAKHA Map 5.1 Ust-Nyukzha Amur Oblast TY NDINS KY 361,900 sq. km Lopcha Lapri Ust-Urkima Baikal-Amur Mainline Tynda CHITA !. ZEISKY Kirovsky Kirovsky Zeiskoe Zolotaya Gora Reservoir Takhtamygda Solovyovsk Urkan Urusha !Skovorodino KHABAROVSK Erofei Pavlovich Never SKOVO MAGDAGACHINSKY Tra ns-Siberian Railroad DIRO Taldan Mokhe NSKY Zeya .! Ignashino Ivanovka Dzhalinda Ovsyanka ! Pioner Magdagachi Beketovo Yasny Tolbuzino Yubileiny Tokur Ekimchan Tygda Inzhan Oktyabrskiy Lukachek Zlatoustovsk Koboldo Ushumun Stoiba Ivanovskoe Chernyaevo Sivaki Ogodzha Ust-Tygda Selemdzhinsk Kuznetsovo Byssa Fevralsk KY Kukhterin-Lug NS Mukhino Tu Novorossiika Norsk M DHI Chagoyan Maisky SELE Novovoskresenovka SKY N OV ! Shimanovsk Uglovoe MAZ SHIMA ANOV Novogeorgievka Y Novokievsky Uval SK EN SK Mazanovo Y SVOBODN Chernigovka !. Svobodny Margaritovka e CHINA Kostyukovka inlin SERYSHEVSKY ! Seryshevo Belogorsk ROMNENSKY rMa Bolshaya Sazanka !. Shiroky Log - Amu BELOGORSKY Pridorozhnoe BLAGOVESHCHENSKY Romny Baikal Pozdeevka Berezovka Novotroitskoe IVANOVSKY Ekaterinoslavka Y Cheugda Ivanovka Talakan BRSKY SKY P! O KTYA INSK EI BLAGOVESHCHENSK Tambovka ZavitinskIT BUR ! Bakhirevo ZAV T A M B OVSKY Muravyovka Raichikhinsk ! ! VKONSTANTINO SKY Poyarkovo Progress ARKHARINSKY Konstantinovka Arkhara ! Gribovka M LIKHAI O VSKY ¯ Kundur Innokentevka Leninskoe km A m Trans -Siberianad Railro u 100 r R i v JAO Russian Far East e r By Newell and Zhou / Sources: Ministry of Natural Resources, 2002; ESRI, 2002. Newell, J. 2004. The Russian Far East: A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development. McKinleyville, CA: Daniel & Daniel. 466 pages CHAPTER 5 Amur Oblast Location Amur Oblast, in the upper and middle Amur River basin, is 8,000 km east of Moscow by rail (or 6,500 km by air). -

Political Machines and Regional Variation in Migration Policies in Russia

Political Machines and Regional Variation in Migration Policies in Russia By Colin Johnson B.A., Rhodes College, 2010 M.A., Brown University, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island 2018 © Copyright 2018 by Colin Johnson This dissertation by Colin Johnson is accepted in its present form by the department of Political Science as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date ________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Linda J. Cook, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date ________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Melani Cammett, Reader Date ________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Douglas Blum, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date ________________ ________________________________________ Dr. Andrew G. Campbell, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Colin Johnson Department of Political Science, Brown University Education d Brown University, Providence, RI. • Ph.D. in Political Science (2018). • M.A. in Political Science (2012). Rhodes College, Memphis, Tennessee. • B.A. in International Studies, Minor in Russian Studies, cum laude (2010). Grants and Fellowships d External • International Advanced Research Opportunity Fellowship, IREX (Sept. 2013–June 2014). • Critical Language Scholarship Program, Kazan, Russia, U.S. Dept. of State (June– Aug. 2010). Brown University -

Information on Tachinid Fauna (Diptera, Tachinidae) of the Phasiinae Subfamily in the Far East of Russia

International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) ISSN: 2249 – 8958, Volume-9 Issue-2, December, 2019 Information on Tachinid Fauna (Diptera, Tachinidae) Of the Phasiinae Subfamily in the Far East of Russia Markova T.O., Repsh N.V., Belov A.N., Koltun G.G., Terebova S.V. Abstract: For the first time, a comparative analysis of the For example, for the Hemyda hertingi Ziegler et Shima tachinid fauna of the Phasiinae subfamily of the Russian Far species described in the Primorsky Krai in 1996 for the first East with the fauna of neighboring regions has been presented. time the data on findings in Western, Southern Siberia and The Phasiinae fauna of the Primorsky Krai (Far East of Russia) is characterized as peculiar but closest to the fauna of the Khabarovsk Krai were given. For the first time, southern part of Khabarovsk Krai, Amur Oblast and Eastern Redtenbacheria insignis Egg. for Eastern Siberia and the Siberia. The following groups of regions have been identified: Kuril Islands, Phasia barbifrons (Girschn.) for Western Southern, Western and Eastern Siberia; Amur Oblast and Siberia, and Elomya lateralis (Mg.) and Phasia hemiptera Primorsky Krai, which share many common Holarctic and (F.) were indicated.At the same time, the following species Transpalaearctic species.Special mention should be made of the have been found in the Primorsky Krai, previously known in fauna of the Khabarovsk Krai, Sakhalin Oblast, which are characterized by poor species composition and Japan (having a Russia only in the south of Khabarovsk Krai and in the subtropical appearance). Amur Oblast (Markova, 1999): Phasia aurigera (Egg.), Key words: Diptera, Tachinidae, Phasiinae, tachinid, Phasia zimini (D.-M.), Leucostoma meridianum (Rond.), Russian Far East, fauna. -

Russian Government Continues to Support Cattle Sector

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 6/17/2013 GAIN Report Number: RS1335 Russian Federation Post: Moscow Russian Government Continues to Support Cattle Sector Report Categories: Livestock and Products Policy and Program Announcements Agricultural Situation Approved By: Holly Higgins Prepared By: FAS/Moscow Staff Report Highlights: Russia’s live animal imports have soared in recent years, as the Federal Government has supported the rebuilding of the beef and cattle sector in Russia. This sector had been in continual decline since the break-up of the Soviet Union, but imports of breeding stock have resulted in a number of modern ranches. The Russian Federal and oblast governments offer a series of support programs meant to stimulate livestock development in the Russian Federation over the next seven years which are funded at hundreds of billions of Russian rubles (almost $10 billion). These programs are expected to lead to a recovery of the cattle industry. Monies have been allocated for both new construction and modernization of old livestock farms, purchase of domestic and imported of high quality breeding dairy and beef cattle, semen and embryos; all of which should have a direct and favorable impact on livestock genetic exports to Russia through 2020. General Information: Trade Russia’s live animal imports have soared in recent years, as the Federal Government has supported the rebuilding of the beef and cattle sector in Russia. This sector has been in decline since the break-up of the Soviet Union, but imports of breeding stock have resulted in a number of modern ranches which are expected to lead to a recovery of the cattle industry. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Republic of Tatarstan 15 I

1 CONTENTS ABOUT AUTHORS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INTRODUCTION 10 THE REPUBLIC OF TATARSTAN 15 I. POLITICAL ELITE 15 1. Vertical power structure 19 2. Governance model during the period of the President M. Shaimiev 20 3. Governance model during the period of the President R. Minnikhanov 22 4. Security forces as part of a consolidated project 27 5. Export of elites 28 II. PRESERVATION OF ETHNO-CULTURAL IDENTITY 30 1.The Tatar national movement 30 2. The Russian national movement 34 3. Language policy in Tatarstan 37 4. Results of post-Soviet language policy 47 5. Conclusion 50 THE REPUBLIC OF DAGESTAN 51 I. DAGESTAN ELITES AND THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT 51 1. Birth of «clans» 53 2. Adaptation to the growing influence of Moscow 56 3. Mukhu Aliev: attempt to be equidistant from clans 58 4. Elite and the Caucasus Emirate 62 5. Return of the «levashintsy» and attempt at a civil dialogue 64 6. First attempt to eliminate clans 66 II. «EXTERNAL GOVERNANCE» 70 III. PRESERVATION OF ETHNO-CULTURAL IDENTITY 79 1. National movements and conflicts 79 2. Preservation of national languages 82 3. Conclusion 91 FINAL CONCLUSIONS 93 2 ABOUT AUTHORS Dr. Ekaterina SOKIRIANSKAIA is the founder and director at Conflict analysis and prevention center. From 2011 to 2017, she served as International Crisis Group’s Russia/North Caucasus Project Director, supervising the organisation’s research and advocacy in the region. From 2008-2011, Sokirianskaia established and supervised the work of Human rights Center Memorial’s regional offices in Kabardino-Balkariya and Dagestan. Before that, from 2003-2008 Sokirianskaia was permanently based in Ingushetia and Chechnya and worked as a researcher and projects director for Memorial and as an assistant professor at Grozny State University.