Political Machines and Regional Variation in Migration Policies in Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Analytical Digest No 7: Migration

No. 7 3 October 2006 rrussianussian aanalyticalnalytical ddigestigest www.res.ethz.ch www.russlandanalysen.de MIGRATION ■ ANALYSIS Immigration and Russian Migration Policy: Debating the Future. Vladimir Mukomel, Moscow 2 ■ TABLES AND DIAGRAMS Migration and Racism 6 ■ REGIONAL REPORT Ethnic Russians Flee the North Caucasus. Oleg Tsvetkov, Maikop 9 ■ REGIONAL REPORT Authorities Hope Chinese Investment Will Bring Russians Back to Far East. Oleg Ssylka, Vladivostok 13 Research Centre for East CSS Center for Security Otto Wolff -Stiftung DGO European Studies, Bremen An ETH Center Studies, ETH Zurich rrussianussian aanalyticalnalytical russian analytical digest 07/06 ddigestigest Analysis Immigration and Russian Migration Policy: Debating the Future By Vladimir Mukomel, Center for Ethno-Political and Regional Studies, Moscow Summary While war refugees and returnees dominated immigration to Russia during the 1990s, in recent years, most immigrants are laborers who want to benefi t from the Russian economic upturn. Th ese immigrants face ex- tremely poor working conditions and they are socially ostracized by the vast majority of the Russian popula- tion. At the same time, immigration could prove to be the solution to the country’s demographic problems, countering the decline of its working population. So far, Russian migration policy has not formulated a convincing response to this dilemma. Introduction about one million immigrants returned to Russia an- he façade of heated political debates over per- nually from the CIS states and the Baltic republics. Tspectives for immigration and migration policy Most of the immigrants who resettled in Russia after disguises a clash of views over the future of Russia. the dissolution of the USSR arrived during this period Th e advocates of immigration – liberals and pragma- (see Fig. -

Mexico and Russia : Mirror Images?

Mexico and Russia : Mirror Images? NIKOLAS K. GVOSDEV D oes Mexico's past experience as a "managed democracy" have any relevante for understanding developments in contemporary Russia?' At first glance, there are important dissimilarities between Mexico and Russia. Russia is the core of a collapsed superpower, with a highly developed industrial and scientific infra- structure; Mexico is a developing nation. Russia has great power pretensions and is a major regional actor, whereas Mexico has subsisted largely in the shadow of its neighbor to the north. However, as far back as the 1940s, American journalist W. L. White suggested that Americans could better understand developments in Russia through a comparison with Mexico 2 More recently, Guillermo O'Don- nell, among others, has drawn important and useful comparisons between the countries of Latin America and Eastern Europe in their respective paths toward democracy, and Robert Leiken, in a recent Foreign Affairs article, has cited the importance of the comparison between Mexico and Russia.3 Russia and Mexico share a number of common elements in their respective political cultures. Mexico's view of itself as an "Ibero-American" fusion of Euro- pean and Indian components is echoed by the notion of Russia as a "Eurasian" society, bridging the gap between European, Islamic, and Asian civilizations. Both countries have strong authoritarian and socialist-communalist currents, which have played a major role in shaping the political culture.4 What is most striking, however, is the degree to which Russia under President Vladimir Putin appears to be moving toward the creation of a political regime of managed democracy that resembles what emerged in Mexico after the 1940s under the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). -

Russia TC Closeout 06-30-12

American International Health Alliance HIV/AIDS Twinning Center Final Performance Report for Russia HRSA Cooperative Agreement No. U97HA04128 Reporting Period: 2009 ‐ 2012 Submitted: June 30, 2012 Preface he American International Health Alliance, Inc. (AIHA) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation created by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and leading representatives of the US healthcare sector in 1992 to serve as the primary vehicle for mobilizing the volunteer spirit of T American healthcare professionals to make significant contributions to the improvement of global health through institutional twinning partnerships. AIHA’s mission is to advance global health through volunteer-driven partnerships that mobilize communities to better address healthcare priorities while improving productivity and quality of care. Founded in 1992 by a consortium of American associations of healthcare providers and of health professions education, AIHA facilitates and manages twinning partnerships between institutions in the United States and their counterparts overseas. To date, AIHA has supported more than 150 partnerships linking American volunteers with communities, institutions, and colleagues in 33 countries in a concerted effort to strengthen health services and delivery, as well as health professions education and training. Operating with funding from USAID; the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services; the US Library of Congress; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; and other donors, AIHA’s partnerships and programs represent one of the US health sector’s most coordinated responses to global health concerns. AIHA’s HIV/AIDS Twinning Center Program was launched in late 2004 to support the US President’s Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). -

The Meltdown of the Russian Federation in the Early 1990S Nationalist Myth-Building and the Urals Republic Project Alexander Kuznetsov

The Meltdown of the Russian Federation in the Early 1990s Nationalist Myth-Building and the Urals Republic Project Alexander Kuznetsov Abstract: In the early 1990s after the collapse of the USSR, the new Russian state faced strong nationalist claims for sovereignty and increased autonomy from the side of regional elites. These nationalist challenges at the sub-national level were seriously considered by many experts to be a potential cause for the further breakup of Russia into a number of new independent states. The nationalist movements in ethnic republics like Chechnya, Tatarstan and Sakha-Yakutia, and their contribution to possible scenario of the disintegration of the Russian Federation, have been researched frequently in post- Soviet-studies literature. However, the examination of the impact of nationalistic ideas in ethnically Russian regions (oblasts) at the beginning of the 1990s has not received the same level of attention from political scientists. The Sverdlovsk oblast is a case study for this research. In the early 1990s, the creation of the Urals republic began in this region. This paper argues that the Sverdlovsk oblast’s claims for increased autonomy included elements of myth-construction within a sub-state nationalist ideology. The first section of this paper briefly contextualizes the events that occurred during the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s that led to the growth of strong sub-nationalist movements in post-Communist Russia. The second section gives details of the Urals republic project, launched in the Sverdlovsk oblast in 1993, and defines the presence of nationalist myth- making elements in this regional movement. -

TW 74 ENG.Pdf

Тurkic Weekly 2017 22 (74) (19 - 25 June ) Тurkic Weekly presents the weekly review of the most significant developments in the Turkic world. Тurkic Weekly provides timely information and an objective assessment on relevant issues in the agenda of Turkic countries. Тurkic Weekly is a weekly information and analytical digest, published by the International Turkic Academy. THE FIFTH WORLD KURULTAI OF KAZAKHS TOOK PLACE IN ASTANA Last week Kazakhstan hosted the 5th World Kurultai of Kazakhs with the participation of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev. The event was held from 22nd to 25th June. On June 22, a grand opening was held. More than 800 delegates took part in the event, 350 of which represent 39 countries. Among them are representatives of sports, state and public organizations. Almost 80% of delegates participate in Kurultai for the first time. As is known, the program of Kurultai is based on the conceptual ideas of the President of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev, outlined in the program article "The Course towards Future: Modernization of Public Consciousness". Speaking to the audience, N.A. Nazarbayev greeted all participants of the World Kurultai who arrived in Astana from 39 countries of the near and far abroad. Nursultan Nazarbayev emphasized the success and reforms implemented in Kazakhstan for 25 years since the first Kurultai. The President of Kazakhstan also separately focused on six projects implemented in the framework of modernization of public consciousness, including transition of the Kazakh alphabet into Latin script, translation of 100 best textbooks of the humanitarian direction, the "Motherland", "Sacred Geography of Kazakhstan", "Modern Kazakhstan culture in the global World","100 new persons of Kazakhstan" projects. -

The Russian Left and the French Paradigm

The Russian Left and the French Paradigm JOAN BARTH URBAN T he resurgence of the post-Soviet Russian communists was almost as unex- pected for many in the West as was Gorbachev's liberalization of the Sovi- et political order. Surprise was unwarranted, however. In the Russian Federation of the early 1990s, hyperinflation triggered by price liberalization and institu- tional breakdown, on top of general economic collapse, deprived a great major- ity of Russian citizens of their life savings and social safety net. It required lit- tle foresight to envision that alienated, militant members of the Soviet-era communist party apparat would have little difficulty rallying electoral support for their reconsituted, restorationist Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF). As it turned out, the CPRF's share of the State Duma's party-list vote rose from 12.4 percent in 1993, to 22.3 percent in 1995, to 24.3 percent in 1999, thereby giving the communists a near monopoly on the oppositionist voice in Russian politics. In this essay, 1 will assess the CPRF's prospects a decade from now. But first it may be instructive to glance back at the failure of most Sovietologists to antic- ipate the likelihood of massive change in the Soviet Union after the passing of the Brezhnev-era generation of leaders. In the early 1980s, the radical reforms of the communist-led Prague Spring of 1968 were still fresh in our memories, even as Solidarity challenged the foundations of communist rule in Poland, the pow- erful Italian Communist Party was rapidly becoming social democratic and in China economic reforms were gaining momentum. -

Russia to “Launder” Warpath the Inf Treaty Iranian Oil?

MONTHLY October 2018 MONTHLY AugustOctober 2018 2018 The publication prepared exclusively for PERN S.A. Date of publication in the public domain: 19th17th NovemberSeptember 2018. 2018. CONTENTS 12 19 28 PUTIN AGAIN ON THE GREAT GAME OVER RUSSIA TO “LAUNDER” WARPATH THE INF TREATY IRANIAN OIL? U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY ADVISOR PUTIN’S ANOTHER BODYGUARD JOHN BOLTON GLADDENED 3 TO BE APPOINTED GOVERNOR 18 MOSCOW’S “PARTY OF WAR” RUSSIAN ARMY TO ADD MORE GREAT GAME OVER THE INF 4 FIREPOWER IN KALININGRAD 19 TREATY PURGE IN RUSSIA’S REGIONS AS RUSSIA AND PAKISTAN TO HOLD PUTIN GETS RID OF POLITICAL JOINT MILITARY DRILLS IN THE 6 VETERANS 21 PAKISTANI MOUNTAINS SECHIN LOSES BATTLE FOR ITALY TO WITHDRAW FROM 7 RUSSIA’S STRATEGIC OIL PORT 22 ROSNEFT PROJECT SPETSNAZ, FLEET AND NUCLEAR GAS GAMES: POLISH-RUSSIANS FORCES: RUSSIA’S INTENSE 24 TENSIONS OVER A NEW LNG DEAL 9 MILITARY DRILLS RUSSIA GETS NEW ALLY AS SHOIGU GAZPROM TO RESUME IMPORTS 25 PAYS VISIT TO MONGOLIA 10 OF TURKMEN GAS MORE TENSIONS IN THE SEA 12 PUTIN AGAIN ON THE WARPATH OF AZOV: RUSSIA TO SCARE ON 27 EASTERN FLANK NOVATEK DISCOVERS NEW 13 PROFITABLE GAS DEPOSITS 28 RUSSIA TO “LAUNDER” IRANIAN OIL? NOT ONLY BALTIC LNG PLANT: MOSCOW HOPES FOR IRAQ’S CLOSE TIES BETWEEN SHELL 29 NEW GOVERNMENT 15 AND GAZPROM GAZPROM AND UKRAINE FACE PUTIN VISITS INDIA TO MARK ANOTHER LITIGATION OVER 16 PURCHASE OF RUSSIA’S MISSILES 31 GAS SUPPLIES www.warsawinstitute.org 2 SOURCE: KREMLIN.RU 8 October 2018 PUTIN’S ANOTHER BODYGUARD TO BE APPOINTED GOVERNOR According to the autumn tradition, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin dismisses some governors while appointing new ones. -

Conference Paper (Aburamoto)

Paper presented at the 5th East Asian Conference on Slavic Eurasian Studies on August 10, 2013 The Role of Regional Elites in Establishing the “United Russia”: Saratov, Samara, and Ul’yanovsk from the Mid-2000s to 2011 Mari Aburamoto JSPS Research Fellow 1. Introduction Russia’s ruling party, “The United Russia” (abbreviated as UR) has provoked the interest of a number of scholars and observers. Some have even described UR as a dominant party (Gel’man 2008, Reuter and Remington 2009). In the 2011 Duma election, however, the situation changed slightly: UR’s mobilization capacity appeared to reach its limits and votes for UR radically decreased compared to the election of 2007. How can this change be explained? UR’s deterioration trend has long been observed in Russia’s regional and local elections. The decline in UR’s popularity should therefore be observed by focusing on the regional and local levels (Panov and Ross 2013). In order to understand the real changes afoot in regional politics, this paper focuses mainly on the configuration of the regional elite groups. Such an approach is also appropriate for understanding the nature of UR. For, as Reuter and Remington (2009) point out, UR’s rise to power was facilitated by organizing the support of regional elites. This paper reveals that the role of regional elites and the elite alignment in each region—that is, the (non-)existence of conflicts between the governor and the mayors and the relative strength of communists as a leading opposition group—both affect UR’s relative strength in each region. -

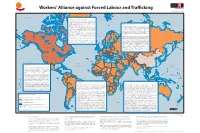

Workers' Alliance Against Forced Labour and Trafficking

165˚W 150˚W 135˚W 120˚W 105˚W 90˚W 75˚W 60˚W 45˚W 30˚W 15˚W 0˚ 15˚E 30˚E 45˚E 60˚E 75˚E 90˚E 105˚E 120˚E 135˚E 150˚E 165˚E Workers' Alliance against Forced Labour and Tracking Chelyuskin Mould Bay Grise Dudas Fiord Severnaya Zemlya 75˚N Arctic Ocean Arctic Ocean 75˚N Resolute Industrialised Countries and Transition Economies Queen Elizabeth Islands Greenland Sea Svalbard Dickson Human tracking is an important issue in industrialised countries (including North Arctic Bay America, Australia, Japan and Western Europe) with 270,000 victims, which means three Novosibirskiye Ostrova Pond LeptevStarorybnoye Sea Inlet quarters of the total number of forced labourers. In transition economies, more than half Novaya Zemlya Yukagir Sachs Harbour Upernavikof the Kujalleo total number of forced labourers - 200,000 persons - has been tracked. Victims are Tiksi Barrow mainly women, often tracked intoGreenland prostitution. Workers are mainly forced to work in agriculture, construction and domestic servitude. Middle East and North Africa Wainwright Hammerfest Ittoqqortoormiit Prudhoe Kaktovik Cape Parry According to the ILO estimate, there are 260,000 people in forced labour in this region, out Bay The “Red Gold, from ction to reality” campaign of the Italian Federation of Agriculture and Siktyakh Baffin Bay Tromso Pevek Cambridge Zapolyarnyy of which 88 percent for labour exploitation. Migrant workers from poor Asian countriesT alnakh Nikel' Khabarovo Dudinka Val'kumey Beaufort Sea Bay Taloyoak Food Workers (FLAI) intervenes directly in tomato production farms in the south of Italy. Severomorsk Lena Tuktoyaktuk Murmansk became victims of unscrupulous recruitment agencies and brokers that promise YeniseyhighN oril'sk Great Bear L. -

Investment Guide to the Republic of Bashkortostan | Ufa, 2017

MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF BASHKORTOSTAN Investment Guide to the Republic of Bashkortostan Ufa 2017 Introduction by Rustem Khamitov, Head of the Republic of Bashkortostan 3 Greetings from Dmitriy Chaban, Managing Partner of Deloitte Ufa 4 Address by Oleg Golov, General Director of the Development Corporation of the Republic of Bashkortostan 5 General information about the Republic of Bashkortostan 6 Seven reasons for doing business in the Republic of Bashkortostan 8 Top-priority sectors for development 16 Government support initiatives for investors 20 Fostering innovation 27 Development institutions 32 Summary of statistics on the economic position of the Republic of Bashkortostan 36 Contacts 38 Investment Guide to the Republic of Bashkortostan Introduction by Rustem Khamitov, Head of the Republic of Bashkortostan Dear Friends, Welcome to the Investment Guide to the Republic Federal mechanisms of investment activity development of Bashkortostan! Bashkortostan is among the leading are used extensively. There is effective cooperation with and dynamically developing regions of Russia. Its location Vnesheconombank and the Monocity Development Fund aimed at the intersection of main traffic arteries, abundant resource at diversifying the economy of the single-industry regions potential, well-developed industry and infrastructure, as well of the republic, as well as increasing the investment inflows as highly skilled labor force, attract investors to our region. to them. One significant event of 2016 was the creation of social and economic development areas in such monocities as Belebey In terms of total investment to subjects of the Russian Federation, and Kumertau, where additional business support tools are used. Bashkortostan today remains in the top ten. -

Grain Crops Consumption of Plant Products

THE ORENBURG REGION ENERGY OF OPPORTUNITIES 2 General information The Orenburg region is the «trading window» from Europe to Asia Norway Finland The shortest trading route Sweden from Moscow to China Helsinki Stockholm Saint-Petersburg through Orenburg – 4 422 km Estonia Latvian Ekaterinburg through Zabaikalsk – 6 641 km Copenhagen Moscow Novosibirsk Lithuania Kazan Minsk Berlin Belarus Irkutsk Germany Warsaw Kiev Entry to Central Asia market Czech RepublicPoland Ukraine Over the past 5 years, the export Austria Kazachstan Ulaanbaatar has grown by: Mongolia Europe › to China – 2,5 times Rome Georgia Uzbekistan 3 days Azerbaijan Tashkent Kyrgyzstan Beijing China › to India – 11% Turkey Turkmenistan Tianjin Ashgabat Kyrgyzstan Kabul Syria Iran Afghanistan 3 days Amman Iraq Tripoli Cairo Transit potential Jordan Iran New Delhi 3 days Nepal More than 600 thousand trucks Libyen Butane Egypt Uzbekistan Doha China pass through the Orenburg Er-Riad UAE India 2 days Bangladesh 4 days Saudi Arabia region of the Russian-Kazakh Myanmar Oman Mumbai Chad Sudan India Yangon border annually Khartum Yemen Eritrea 6 days Bangkok N'djamena Thailand Vietnam Nigeria Cambodia Addis Ababa Somalia CAR Southern Sudan Ethiopia Sri Lanka 3 General information The Orenburg region on the map of Russia GTM + 05:00 Orenburg 123,7 km2 2 mil. people 72 years time zone regional center total area population average life span Petrozavodsk bln. ₽ 1 006,4 2018 823,9 2017 Vologda 765,3 2016 Kirov Perm 775,1 2015 Rybinsk Nishnij Tagil YaroslavlKostroma 2,2 times 731,3 2014 Yekaterinburg Tyumen Tver Ivanovo Nizhny Izhevsk 717,1 2013 Novgorod GRP growth in 2 hours Yoshkar-Ola 2010-2018 628,6 2012 Cheboksary Kazan Moscow 20 hours Chelyabinsk Kurgan 553,3 2011 Nizhnekamsk Ufa 25 hours 458,1 2010 Kaluga Petropavl Tula Ulyanovsk Sterlitamak Kostanai Penza Tolyatti Magnitogorsk Tambov % % Lipetsk Samara 103,2 3,7 Saratov Industrial Unemployment Voronezh Kursk Orenburg production index rate Uralsk Aktobe 211,7 bln. -

The Mineral Indutry of Russia in 1998

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF RUSSIA By Richard M. Levine Russia extends over more than 75% of the territory of the According to the Minister of Natural Resources, Russia will former Soviet Union (FSU) and accordingly possesses a large not begin to replenish diminishing reserves until the period from percentage of the FSU’s mineral resources. Russia was a major 2003 to 2005, at the earliest. Although some positive trends mineral producer, accounting for a large percentage of the were appearing during the 1996-97 period, the financial crisis in FSU’s production of a range of mineral products, including 1998 set the geological sector back several years as the minimal aluminum, bauxite, cobalt, coal, diamonds, mica, natural gas, funding that had been available for exploration decreased nickel, oil, platinum-group metals, tin, and a host of other further. In 1998, 74% of all geologic prospecting was for oil metals, industrial minerals, and mineral fuels. Still, Russia was and gas (Interfax Mining and Metals Report, 1999n; Novikov significantly import-dependent on a number of mineral products, and Yastrzhembskiy, 1999). including alumina, bauxite, chromite, manganese, and titanium Lack of funding caused a deterioration of capital stock at and zirconium ores. The most significant regions of the country mining enterprises. At the majority of mining enterprises, there for metal mining were East Siberia (cobalt, copper, lead, nickel, was a sharp decrease in production indicators. As a result, in the columbium, platinum-group metals, tungsten, and zinc), the last 7 years more than 20 million metric tons (Mt) of capacity Kola Peninsula (cobalt, copper, nickel, columbium, rare-earth has been decommissioned at iron ore mining enterprises.