SUDAN: IDP Crisis Worsens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shelter/Nfi Analysis Report 1

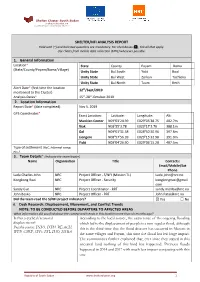

Shelter Cluster South Sudan sheltersouthsudan.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER/NFI ANALYSIS REPORT Field with (*) and italicized questions are mandatory. For checkboxes (☐), tick all that apply. Use charts from mobile data collection (MDC) wherever possible. 1. General Information Location* State County Payam Boma (State/County/Payam/Boma/Village) Unity State Bul South Yidit Bool Unity State Bul West Zorkan Tochloka Unity State Bul North Taam Kech Alert Date* (first time the location 12th/Sept/2019 mentioned to the Cluster) Analysis Dates* 15th-28th-October-2019 2. Location Information Report Date* (date completed) Nov 5, 2019 GPS Coordinates* Exact Location: Latitude: Longitude: Alt: Mankien Center N09003’24.99 E029005’38.75 402.7m Riak N08055’3.78 E029017’3.70 388.1m Gol N09001’31.38 E028050’40.96 397.8m Liengere N08057’56.39 E029015’32.98 391.0m Yidit N09004’26.90 E029006’15.20 407.5m Type of settlement (PoC, informal camp, etc.) 3. Team Details* (Indicate the team leader) Name Organisation Title Contacts: Email/Mobile/Sat Phone Ladu Charles John NRC Project Officer - S/NFI (Mission TL) [email protected] Kongkong Ruei NRC Project Officer - Security kongkongruei@gmail. com Sandy Gur NRC Project Coordinator - RRT [email protected] John Bosko NRC Project Officer - RRT [email protected] Did the team read the S/NFI project indicators? ☒ Yes ☐ No 4. Desk Research: Displacement, Movement, and Conflict Trends NOTE: TO BE CONDUCTED BEFORE DEPARTURE TO AFFECTED AREAS What information did you find about the context and trends in this location more than six months ago? Is this a cyclical/seasonal According to the local source, the occurrence of the ongoing flooding displacement? which led to the displacement of people is a non-regular flood, although Possible sources: INSO, DTM, REACH, this is the third time that the flood disaster has occurred in Mayom in WFP, CSRF, SFPs, FSL IMO, HSBA the same villages and Payam, this time the flood has left huge impact. -

Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014

IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014 Important: - IRNA Report should include secondary data collected by all stakeholders and jointly analyzed - IRNA Report should also include community level assessment analysis by clusters and then jointly analyzed by all stakeholders - Report should adequately cover the de-briefing analysis of assessment team leaders - This report should be produced within two days after the IRNA taking place 1 IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Situation Overview (use the secondary information as well as the information gathered under the ‘Generalist’ section of the IRNA questionnaire. Map Drivers of Crisis and underlying factors Place map of affected area if available Conflict has spread across South Sudan following an alleged coup attempt three weeks ago in Juba. Among the states directly affected by the crisis is Unity State which neighbours Warrap State to the East. An influx of Internally Displaced People (IDPs) into Warrap’s Twic County has steadily increased since the last week of December Affected population: 2013. Most of those IDPs have been directly attacked or been caught (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) up in the cross fire during the fighting that has ensued in Unity State, while some have run out of seer fear. Displaced population: (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) Scope of crisis and humanitarian profile Most of the displaced are from Mayom County in Unity State, while 3,215 individuals some have been displaced from as far as Bentiu town the Unity State with possible increase in coming days capital itself, in Rubkona County. -

The War(S) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace

Conflict Research Programme The War(s) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace Flora McCrone in collaboration with the Bridge Network About the Authors Flora McCrone is an independent researcher based in East Africa. She has specialised in research on conflict, armed groups, and political transition across the Horn region for the past nine years. Flora holds a master’s degree in Human Rights from LSE and a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Durham University. The Bridge Network is a group of eight South Sudanese early career researchers based in Nimule, Gogrial, Yambio, Wau, Leer, Mayendit, Abyei, Juba PoC 1, and Malakal. The Bridge Network members are embedded in the communities in which they conduct research. The South Sudanese researchers formed the Bridge Network in November 2017. The team met annually for joint analysis between 2017-2020 in partnership with the Conflict Research Programme. About the Conflict Research Programme The Conflict Research Programme is a four-year research programme hosted by LSE IDEAS, the university’s foreign policy think tank. It is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Our goal is to understand and analyse the nature of contemporary conflict and to identify international interventions that ‘work’ in the sense of reducing violence or contributing more broadly to the security of individuals and communities who experience conflict. © Flora McCrone and the Bridge Network, February 2021. This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Following the Thread: Arms and Ammunition Tracing in Sudan and South Sudan

32 Following the Thread: Arms and Ammunition Tracing in Sudan and South Sudan By Jonah Leff and Emile LeBrun Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2014 First published in May 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Tania Inowlocki Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-9700897-1-1 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 32 Contents List of boxes, figures, maps, and tables .......................................................................................................................... 5 List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

South Sudan: Compounding Instability in Unity State

SOUTH SUDAN: COMPOUNDING INSTABILITY IN UNITY STATE Africa Report N°179 – 17 October 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. STATE ORIGINS AND CHARACTERISTICS ............................................................ 1 III. LEGACY OF WAR ........................................................................................................... 3 IV. POLITICAL POLARISATION AND A CRISIS OF GOVERNANCE ...................... 4 A. COMPLAINTS LODGED ................................................................................................................. 5 B. PARTY POLITICS: A HOUSE DIVIDED ........................................................................................... 6 C. TENSE GUBERNATORIAL ELECTION ............................................................................................. 7 D. THE DIVIDE REMAINS .................................................................................................................. 8 V. NATIONAL POLITICS AT PLAY ................................................................................. 8 VI. REBEL MILITIA GROUPS AND THE POLITICS OF REBELLION .................... 10 A. MILITIA COMMANDERS AND FLAWED INTEGRATION ................................................................. 11 B. THE STAKES ARE RAISED: PETER GADET .................................................................................. -

Download the Full Report

HUMAN RIGHTS “We Can Die Too” Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in South Sudan WATCH “We Can Die Too” Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in South Sudan Copyright ©2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-33092 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2015 978-1-6231-33092 “We Can Die Too” Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in South Sudan Map of South Sudan .......................................................................................................... i Glossary .......................................................................................................................... ii Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .......................................................................................................... -

Gogrial West, Twic and Mayom Counties Food Security and Livelihoods Profile South Sudan, October 2018

Gogrial West, Twic and Mayom Counties Food Security and Livelihoods Profile South Sudan, October 2018 Introduction Key Findings During the September 2018 Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) for • Heightened insecurity in June 2017 resulted in mass South Sudan food security direct outcome indicators for Gogrial West displacement from the eastern bank of Jur river in Gogrial and Twic counties in Warrap state and Mayom county in Unity state West county, Warrap state, to multiple locations along the Wau were indicative of severe food consumption gaps.1 Preliminary data – Turelei road, with most IDPs relying on relatives and social from the World Food Programmes’ (WFP) food security and nutrition networks to access food. Compounding factors, including poor monitoring system (FSNMS) reported HHs with Household Hunger harvest yields, limited access to cattle, and over-extraction of Score of 5-6, which can be indicative of populations in IPC phase 4 or local resources, have severely reduced availability and access 5.2 Additionally, SMART surveys that were conducted in each county to food. As a result, FGD participants in Gogrial West and between May and August reported the GAM prevalence in the three Twic counties anticipated that the level of food insecurity counties was above the World Health Organization (WHO) thresholds during the upcoming lean season will be comparable to for emergency. However, the contributing factors were not clearly previous years when the communities experienced extreme highlighted and further ground truthing was suggested. The concerns hunger, such as 1998. were raised at the Inter-Cluster Working Group (ICWG) in the first • Atypical flooding in Twic county, Warrap state, has displaced week of October and approved for a follow-up assessment. -

County Social Map County Social

COUNTYCOUNTY SOSOCIALCIAL MAP MAYOMABANM CCOUNTYOUNTY SOUTSOUTH SUSUDAN OVERVIEW In April 2015, a vaccine-derived poliovirus (vDPV) case was detected in Mayom County. After the formation of Northern Liech State, it became one of the four, as well as the largest, county of the state. It borders Abiemnom to the north, Rubkona to the east, Koch to the south, and Warrap to the west. Due to its strategic location and political BIEH PUP/ MAYOM significance, it became important for programme intervention. TAAM R. NGOP Kiir (Bahr el-Arab) KEY CHALLENGES NUERYIEK RUATHNYIBUOL KUERBUONEKUERBUONE MANKIEN • Cattle camps along the river and swamp areas are difficult to access round the year RIAK • Road connectivity through Warrap State • Flood during rainy seasons makes payams inaccessible in WANGBUOR most cases ANGKEI • Most payams do not have functional cold chain W Risk • Very poor road network • Alternate occurrences of flood and drought Low Medium RISK AND ACCESS ANALYSIS High With regard to risk, Mayom County can be divided into two zones – high and low risk. The northern and southern border areas of the county, featuring parts of Riaak, Ruadh, Kueryiek, Ngop, Bieh, Wangbuor and Wangkai payams, are in the high-risk zone. The rest of the county is in the low-risk zone. With regard to accessibility, river, rain and flood are three crucial FAST FACTS factors. Most parts of Mayom, Mankien and Wangbuor become flooded during the rainy season and remain isolated throughout • Payams: 11 the season. The northern areas of the county, comprising Riaak, • Bomas: 45 Ruadh, Kueryiek, Ngop and Bieh, often become inaccessible due to cattle raiding. -

The Politics of Numbers: on Security Sector Reform in South Sudan, 2005-2020

The Politics of Numbers: On Security Sector Reform in South Sudan, 2005-2020 Joshua Craze © Joshua Craze. Flooding in Akobo, November 2019 The Politics of Numbers: On Security Sector Reform in South Sudan, 2005-2020 Joshua Craze Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 2. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 10 3. The Limits of Payroll Peace: On CPA-era Security Sector Reform …………………….... 17 The Revenge of the Jobbists 17 The Creation of a Military Aristocracy 19 The CPA Period 21 The Big Tent 24 Make Believe 27 The Limits of Payroll Peace 31 4. The ARCSS: An Engine Not a Camera ………………………………………………………………….. 36 5. The R-ARCSS ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 42 Building a ‘real’ army 44 The Politics of Numbers 46 The Politics of Time 49 Already integrated: DDR in the R-ARCSS 53 6. Cantonment ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 55 The where of cantonment 58 The who of cantonment 59 7. Cantonment Case Studies ……………………….…………………………………………..………………….. 65 Case study I: Failed Cantonment in Akobo 68 Case Study II: Splitting the Opposition 71 Case Study III: Not the Opposition 76 Case Study IV: The Fiction of Unity 79 Case Study V: The Unity of the Fiction 81 Case Study VI: The Appearance of Difference 83 8. The Government’s Position ……………………….…………………………………………..……………….. 87 9. The Training of the Necessary Unified Force ……………………………………………………….. 93 10. Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 97 …………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Bibliography 104-109 1. Executive Summary ‘There will not be Oye, there will not be Viva, there will be South Sudan Victory, and we will 1 dissolve all our identities.’ th – Major General Abraham Gum Makwac, SSPDF 5 Division Commander, 3 March 2020 In the quote that begins this report, Makwac articulates a hopeful vision of the security sector reform (SSR) process of the 2018 Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS). -

Unity State Contents

SOCIAL MAPPING South Sudan Unity State CONTENTS About social mapping 2 About Unity State 3 Unity State map: South Sudan 4 General information 5 Demographic details 6 Communication interface mapping 7 High risk groups 8 Nomads 10 Logistics management mapping 12 Partners mapping 14 Accessibility mapping 16 Key factors that deprive children of immunization 18 ABOUT SOCIAL MAPPING The purpose of social mapping is to facilitate microplanning for communication for development interventions for polio campaigns and routine immunization. Communication and Public Health professionals working in the field of polio eradication and routine immunization are expected to use this document as a reference manual. Unity State is the focus of this report. It begins with an overview of the State, including general Information and demographics. It then addresses the following social mapping components: • Communication interfaces • Logistics management • Partners • Accessibility • Key factors that deprive children of South Sudan of immunization 2 ABOUT UNITY STATE Unity State is the subject of social mapping for a variety of reasons. While Unity is one of the 10 states of South Sudan, it is better known as one of the three conflict-affected states in the country. Due to its geographic location and association with the Greater Upper Nile region, Unity is also known as Western Upper Nile. It covers an area of 38,837 sq km (14,995 sq mi) and is inhabited predominantly by two ethnic groups – the Nuer and the Dinka. Its economy is primarily agricultural but it is also rich in oil resources. Southern Sudan’s first oil reserves were discovered in this region during the 1970s. -

South Sudan at 10

South Sudan at 10 An MSF record of the consequences of violence South Sudan at 10 | 1 Acronyms AWSD Aid Worker Security Database CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement CMR Crude Mortality Rate EU European Union GPAA Greater Pibor Administrative Area GDP Gross Domestic Product HRW Human Rights Watch IDP Internally Displaced Person ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross IHL International Humanitarian Law IRC International Rescue Committee IPV Intimate Partner Violence MSF Médecins Sans Frontières MoH Ministry of Health NGO Non-Governmental Organisation OCHA United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs OHCHR Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights PTSD Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder PoC Protection of Civilians site ROSS Republic of South Sudan RPG Rocket Propelled Grenade SMC Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention SAM Severe Acute Malnutrition SGBV Sexual and Gender-Based Violence SSLS South Sudan Law Society SSPDF South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (formerly the SPLA) SPLA Sudan People’s Liberation Army (now the SSPDF) SPLA-IO Sudan People’s Liberation Army-In Opposition SPLA-N Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North SAF Sudanese Armed Forces TB Tuberculosis UN United Nations UNICEF United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund UNMISS United Nations Mission in South Sudan UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees WFP World Food Programme WHO World Health Organization Acknowledgements Special thanks to Cover image Art direction, design + infographics MSF wishes to acknowledge all of its The more than 100 MSF South ©Anna Surinyach. Displaced people Sue Cowell | www.atomodesign.nl staff and patients in South Sudan. Sudanese staff who contributed to within the UNMISS compound in this report;* and to Duncan McLean; Malakal Protection of Civilians site, Boundaries and place names on Authors Pete Buth; Lauren King; Marc South Sudan. -

A Fractious Rebellion: Inside the SPLM-IO

39 A Fractious Rebellion: Inside the SPLM-IO By John Young Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in September 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-17-0 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 39 Contents Acronyms and abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction and key findings ............................................................................................................................................... 6 II. Background ...................................................................................................................................................................................................