S/2018/865 Security Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shelter/Nfi Analysis Report 1

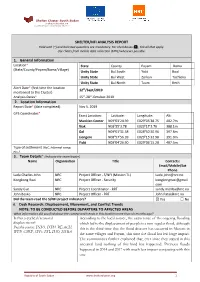

Shelter Cluster South Sudan sheltersouthsudan.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER/NFI ANALYSIS REPORT Field with (*) and italicized questions are mandatory. For checkboxes (☐), tick all that apply. Use charts from mobile data collection (MDC) wherever possible. 1. General Information Location* State County Payam Boma (State/County/Payam/Boma/Village) Unity State Bul South Yidit Bool Unity State Bul West Zorkan Tochloka Unity State Bul North Taam Kech Alert Date* (first time the location 12th/Sept/2019 mentioned to the Cluster) Analysis Dates* 15th-28th-October-2019 2. Location Information Report Date* (date completed) Nov 5, 2019 GPS Coordinates* Exact Location: Latitude: Longitude: Alt: Mankien Center N09003’24.99 E029005’38.75 402.7m Riak N08055’3.78 E029017’3.70 388.1m Gol N09001’31.38 E028050’40.96 397.8m Liengere N08057’56.39 E029015’32.98 391.0m Yidit N09004’26.90 E029006’15.20 407.5m Type of settlement (PoC, informal camp, etc.) 3. Team Details* (Indicate the team leader) Name Organisation Title Contacts: Email/Mobile/Sat Phone Ladu Charles John NRC Project Officer - S/NFI (Mission TL) [email protected] Kongkong Ruei NRC Project Officer - Security kongkongruei@gmail. com Sandy Gur NRC Project Coordinator - RRT [email protected] John Bosko NRC Project Officer - RRT [email protected] Did the team read the S/NFI project indicators? ☒ Yes ☐ No 4. Desk Research: Displacement, Movement, and Conflict Trends NOTE: TO BE CONDUCTED BEFORE DEPARTURE TO AFFECTED AREAS What information did you find about the context and trends in this location more than six months ago? Is this a cyclical/seasonal According to the local source, the occurrence of the ongoing flooding displacement? which led to the displacement of people is a non-regular flood, although Possible sources: INSO, DTM, REACH, this is the third time that the flood disaster has occurred in Mayom in WFP, CSRF, SFPs, FSL IMO, HSBA the same villages and Payam, this time the flood has left huge impact. -

Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014

IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014 Important: - IRNA Report should include secondary data collected by all stakeholders and jointly analyzed - IRNA Report should also include community level assessment analysis by clusters and then jointly analyzed by all stakeholders - Report should adequately cover the de-briefing analysis of assessment team leaders - This report should be produced within two days after the IRNA taking place 1 IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Situation Overview (use the secondary information as well as the information gathered under the ‘Generalist’ section of the IRNA questionnaire. Map Drivers of Crisis and underlying factors Place map of affected area if available Conflict has spread across South Sudan following an alleged coup attempt three weeks ago in Juba. Among the states directly affected by the crisis is Unity State which neighbours Warrap State to the East. An influx of Internally Displaced People (IDPs) into Warrap’s Twic County has steadily increased since the last week of December Affected population: 2013. Most of those IDPs have been directly attacked or been caught (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) up in the cross fire during the fighting that has ensued in Unity State, while some have run out of seer fear. Displaced population: (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) Scope of crisis and humanitarian profile Most of the displaced are from Mayom County in Unity State, while 3,215 individuals some have been displaced from as far as Bentiu town the Unity State with possible increase in coming days capital itself, in Rubkona County. -

The War(S) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace

Conflict Research Programme The War(s) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace Flora McCrone in collaboration with the Bridge Network About the Authors Flora McCrone is an independent researcher based in East Africa. She has specialised in research on conflict, armed groups, and political transition across the Horn region for the past nine years. Flora holds a master’s degree in Human Rights from LSE and a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Durham University. The Bridge Network is a group of eight South Sudanese early career researchers based in Nimule, Gogrial, Yambio, Wau, Leer, Mayendit, Abyei, Juba PoC 1, and Malakal. The Bridge Network members are embedded in the communities in which they conduct research. The South Sudanese researchers formed the Bridge Network in November 2017. The team met annually for joint analysis between 2017-2020 in partnership with the Conflict Research Programme. About the Conflict Research Programme The Conflict Research Programme is a four-year research programme hosted by LSE IDEAS, the university’s foreign policy think tank. It is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Our goal is to understand and analyse the nature of contemporary conflict and to identify international interventions that ‘work’ in the sense of reducing violence or contributing more broadly to the security of individuals and communities who experience conflict. © Flora McCrone and the Bridge Network, February 2021. This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Following the Thread: Arms and Ammunition Tracing in Sudan and South Sudan

32 Following the Thread: Arms and Ammunition Tracing in Sudan and South Sudan By Jonah Leff and Emile LeBrun Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2014 First published in May 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Tania Inowlocki Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-9700897-1-1 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 32 Contents List of boxes, figures, maps, and tables .......................................................................................................................... 5 List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

A Case Study of South Sudan by Moses

AN EXAMINATION OF THE ROLE OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION MECHANISMS IN ARMED CONFLICT SITUATIONS: A CASE STUDY OF SOUTH SUDAN BY MOSES MAKER MAGOK LLB/16625/113/D F A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF LAW IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AW ARD OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF LAWS OF KAMP ALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY JANUARY, 2017 DECLARATION "I MOSES MAKER MAGOK declare that the work presented in this dissertation is original. It has never been presented to any other University or Institution. It is hereby presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Bachelor Degree in Law of Kampala International University". Signature: --~ -------- Date: _{?_ _j_~J~J:j- APPROVAL BY THE SUPERVISOR "I certify that I have supervised and read this study and that in my opinion, it conforms to acceptable standards of scholarly presentation and is fully in scope and quality as a di ssertation in partial fulfillment for the award of Degree of Bachelor of Law of Kampala International University". Name of Supervisor: Mr.Tajudeen Sanni Signature: -- ~ ------------ Date: ------b/J ---------------')_--- -------------1---:::r-- --------- ( ii DEDICATION I dedicate this book to my dear and lovely wife Deborah Yar Majok and the entire family of Dhor Athian Liai and to my parents both Dad and Mum namely: Magok Majok Dhor and lovely Mum Mary Nyitur Y omdit for their adequate supports and prayers they rendered to me during my studies that gave me success leading to award of Bachelor Degree of Laws of Kampala International University. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who deserve special thanks for helping me in getting the information about this research topic of which it had facilitated the completion of my thesis. -

Small Arms Survey/HSBA: "The Conflict in Unity State"

The Conflict in Unity State Describing events through 29 January 2015 It is now thirteen months since the beginning of the South Sudanese conflict. Both the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO) have spent the rainy season reinforcing their military positions in Unity state—as elsewhere—in anticipation of a dry season military campaign. The beginning of 2015 has already seen clashes just south of Bentiu—the state capital—in Guit county, and around the oil fields of Rubkona and Pariang counties. As of January 2015, the SPLA maintains control of the northern and western counties of Pariang and Abiemnom, as well as of Bentiu. The SPLA-IO controls Unity’s southern counties, and much of Guit and Rubkona. Mayom, a strategically important county that contains the road from Warrap state— along which SPLA reinforcements could travel—is largely under the control of the SPLA. As dry season begins, the frontlines are just south of Bentiu, in Guit and Rubkona, and just north and west of the oil fields in Rubkona and Pariang: both the oil fields and the state capital will be important SPLA-IO strategic targets in the coming months. Peace negotiations, which continued during the rainy season, have failed to overcome the substantial divergences between the two sides’ positions. An intra-SPLM dialogue recently took place in Arusha, Tanzania, and resulted in an agreement signed on 21 January by the SPLM, SPLM-IO, and the representative of the SPLM detainees, Deng Alor. -

South Sudan Development Plan 2011-2013

Government of the Republic of South Sudan South Sudan Development Plan 2011-2013 Realising freedom, equality, justice, peace and prosperity for all Juba, August 2011 0 Contents 0.1 Table of abbreviations and acronyms v 0.2 Foreword xi 0.3 Acknowledgments xii 0.4 Executive summary xiii 0.4.1 Context: conflict, poverty and economic vulnerability xiii 0.4.2 The development challenge xiii 0.4.3 Development objectives xiv 0.4.4 Governance – institutional strengthening and improving transparency and accountability xvi 0.4.5 Economic development – rural development supported by infrastructure improvements xvii 0.4.6 Social and human development – investing in people xviii 0.4.7 Conflict prevention and security – deepening peace and improving security xix 0.4.8 Cross-cutting issues xx 0.4.9 Government resources and their allocation to support development priorities xx 0.4.10 Donor resources xxi 0.4.11 Implementation xxii 0.4.12 Monitoring and Evaluation xxiii 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE SOUTH SUDAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN 1 1.1 Purpose of the South Sudan Development Plan 1 1.2 The development planning process and approach 1 1.3 Coverage of the South Sudan Development Plan 2 1.4 Cross-cutting issues integral to the national development priorities 3 2 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 4 2.1 Historical context 4 2.2 Analysis of conflict 6 2.2.1 Causes of conflict 6 2.2.2 Consequences of conflict 8 2.2.3 Peace-building in South Sudan 8 2.2.4 Recommendations for SSDP 11 2.3 Poverty and human development 12 2.3.1 Demographic context 13 2.3.2 Vulnerability 16 2.3.3 Social -

South Sudan: Compounding Instability in Unity State

SOUTH SUDAN: COMPOUNDING INSTABILITY IN UNITY STATE Africa Report N°179 – 17 October 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. STATE ORIGINS AND CHARACTERISTICS ............................................................ 1 III. LEGACY OF WAR ........................................................................................................... 3 IV. POLITICAL POLARISATION AND A CRISIS OF GOVERNANCE ...................... 4 A. COMPLAINTS LODGED ................................................................................................................. 5 B. PARTY POLITICS: A HOUSE DIVIDED ........................................................................................... 6 C. TENSE GUBERNATORIAL ELECTION ............................................................................................. 7 D. THE DIVIDE REMAINS .................................................................................................................. 8 V. NATIONAL POLITICS AT PLAY ................................................................................. 8 VI. REBEL MILITIA GROUPS AND THE POLITICS OF REBELLION .................... 10 A. MILITIA COMMANDERS AND FLAWED INTEGRATION ................................................................. 11 B. THE STAKES ARE RAISED: PETER GADET .................................................................................. -

JMEC-1St-Qtr-2020-Report-FINAL 1.Pdf

REPORT BY H.E AMB. LT. GEN AUGOSTINO S.K. NJOROGE (Rtd) INTERIM CHAIRPERSON OF RJMEC ON THE STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE REVITALISED AGREEMENT ON THE RESOLUTION OF THE CONFLICT IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FOR THE PERIOD 1st January to 31st March 2020 Report No. 006/20 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN Table of Contents List of Acronyms ....................................................................................................................... ii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. iii I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 II. Prevailing Political, Security, Humanitarian and Economic Situation ................................. 2 Political Developments .......................................................................................................... 2 The Security Situation ............................................................................................................ 3 Humanitarian Situation .......................................................................................................... 5 The Economy ......................................................................................................................... 7 III. Status of Implementation of the R-ARCSS ......................................................................... 8 Number of States and Boundaries ......................................................................................... -

Displaced and Immiserated: the Shilluk of Upper Nile in South

Report September 2019 DISPLACED AND IMMISERATED The Shilluk of Upper Nile in South Sudan’s Civil War, 2014–19 Joshua Craze HSBA DISPLACED AND IMMISERATED The Shilluk of Upper Nile in South Sudan’s Civil War, 2014–19 Joshua Craze HSBA A publication of the Small Arms Survey’s Human Security Baseline Assessment for Sudan and South Sudan project with support from the US Department of State Credits Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, 2019 First published in September 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Coordinator, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Rebecca Bradshaw Fact-checker: Natacha Cornaz ([email protected]) Copy-editor: Hannah Austin ([email protected]) Proofreader: Stephanie Huitson ([email protected]) Cartography: Jillian Luff, MAPgrafix (www.mapgrafix.com) Design: Rick Jones ([email protected]) Layout: Frank Benno Junghanns ([email protected]) Cover photo: A man walks through the village of Aburoc, South Sudan, as an Ilyushin Il-76 flies over the village during a food drop as part of a joint WFP–UNICEF Rapid Response Mission on 13 May 2017. -

Full List of the Historical SPLM/SPLA Commanders, 1983-2005

The historical list of the SPLA commanders after 1991 split and merging of the two SPLA (SPLA –Torit and SPLA Nasir factions): S/n Rank Name in full Date of Remarks promotion 1. Cdr Dr. John Garang De Mabior 15/5/1983 2. Cdr Salva Kiir Mayardit 15/5/1983 3. Cdr Dr. Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon 4. Cdr James Wani Igga 1/1/1986 5. Cdr Daniel Awet Akot 1/1/1986 6. Cdr Kuol Manyang Juuk 1/1/1986 7. Cdr Lual Diing Wol 1/1/1989 8. Cdr Stephen Duol Chuol 1/1/1988 9. Cdr Pagan Amum Okiech 16/5/1991 10. Cdr Deng Alor Kuol 16/5/1991 11. Cdr John Kong Nyuon 16/5/1991 12. Cdr Abdel; Aziz Adam El Hilu 16/5/1991 13. Cdr Samuel Abujohn Kabashi 16/5/1991 14. Cdr Nhial Deng Nhial 16/5/1991 15. Cdr Malik Agar Eyre 16/5/1991 16. Cdr Stephen Madut Baak 1/11/1991 17. Cdr Bona Bang Dhol 1/11/1991 18. Cdr Elijah Malok Aleng 1/11/1991 19. Cdr Cagai Atem Biar 1/11/1991 20. Cdr Mark Machiec Magok 1/11/1991 21. Cdr Kuot Deng Kuot 1/11/1991 22. Cdr Anthony Bol Madut 1/11/1991 23. Cdr Akec Koc Acieu 1/11/1991 24. Cdr Peter Wal Athieu 1/11/1991 25. Cdr Oyai Deng Ajak 1/11/1991 26. Cdr Dominic Dim Deng 1/11/1991 27. Cdr Salva Mathok Geng 1/11/1991 28. Cdr Bior Ajang Duot 1/11/1991 29. -

(UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT

United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) Media & Spokesperson Unit Communications & Public Information Office MEDIA MONITORING REPORT MONDAY, 08 JULY 2013 SOUTH SUDAN South Sudan’s 2nd birthday (Al-Jazeera News) Friends of S. Sudan’ go public with call for "significant changes and reform" (Sudantribune.com) Dr. Tedros Receives South Sudan's Foreign Minister (AllAfrica.com) South Sudan not a failed state: British Envoy (Gurtong.net) O3b’s new satellite constellation to provide high speed connectivity to S. Sudan (Business Wire) Youth want leader to step down for abuse of office (Gurtong.net) Japan boosts Ministry of Health with USD 4 million by Anthony Wani (Theniles.org) South Sudanese students in Egypt meet government delegation (Gurtong.net) CARE International assists vulnerable communities in Unity state (Sudantribune.com) Organization distributes treated mosquito nets to curb malaria spread (Gurtong.net) SOUTH SUDAN, SUDAN FM to represent Sudan in S. Sudan national day celebrations (Sudanvisiondaily.com) Sudan MiG-29s said to conduct air strikes on South (Worldtribune.com) SAF denies Juba accusations of fresh attacks on border areas (Sudantribune.com) Now is the time for Arab Unity; Nafie (Sudanvisiondaily.com) Eritrea’s leader says comprehensive strategy key to resolve Sudans disputes (Sudantribune.com) South Sudan’s FM briefs Ethiopian PM about recent talks with Khartoum (Sudantribune.com) Juba says Khartoum wants to buy 4,500 barrels of oil for Kosti power plant (Sudantriibune.com) Sudan will not shut oil