The Politics of Numbers: on Security Sector Reform in South Sudan, 2005-2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’S Newest Country

The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Ted Dagne Specialist in African Affairs July 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41900 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Summary In January 2011, South Sudan held a referendum to decide between unity or independence from the central government of Sudan as called for by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that ended the country’s decades-long civil war in 2005. According to the South Sudan Referendum Commission (SSRC), 98.8% of the votes cast were in favor of separation. In February 2011, Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir officially accepted the referendum result, as did the United Nations, the African Union, the European Union, the United States, and other countries. On July 9, 2011, South Sudan is to officially declare its independence. The Obama Administration welcomed the outcome of the referendum and pledged to recognize South Sudan as an independent country in July 2011. The Administration is expected to send a high-level presidential delegation to South Sudan’s independence celebration on July 9, 2011. A new ambassador is also expected to be named to South Sudan. South Sudan faces a number of challenges in the coming years. Relations between Juba, in South Sudan, and Khartoum are poor, and there are a number of unresolved issues between them. The crisis in the disputed area of Abyei remains a contentious issue, despite a temporary agreement reached in mid-June 2011. -

Addis PEACE a 411St ME HEADS O BANJUL, 30 DECEM AFRICAN

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, P.O. Box: 3243 Tel.: (251‐11) 5513 822 Fax: (251‐11) 5519 321 Email: situationroom@africa‐union.org PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL 411st MEETING AT THE LEVEL OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT BANJUL, THE GAMBIA 30 DECEMBER 2013 PSC/AHG/3(CDXI) REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OFF THE COMMISSION ON THE SITUATION IN SOUTH SUDAN PSC/AHG/3(CDXI) Page 1 REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION ON THE SITUATION IN SOUTH SUDAN I. INTRODUCTION 1. The present report is submitted in the context of the meeting of Council to be held in Banjul, The Gambia, on 30 December 2013, to deliberate on the unfolding situation in South Sudan. The conflict in South Sudan erupted on 15 December, in the context of a political challenge to the President of the Republic of South Sudan, from leading members of the ruling party, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). This rapidly mutated into violent confrontation and rebellion. The conflict imperils the lives and wellbeing of South Sudanese, jeopardizes the future of the young nation, and is a threat to regional peace and security. 2. The report provides a background to the current crisis, a chronology of the events of the last six months and an overview of the regional, continental and international response. The report concludes with observations on the way forward. II. BACKGROUND 3. The current conflict represents the accumulation of unresolved political disputes within the leadership of the SPLM. The leaders had disagreements on fundamental aspects of the party and country’s leadership, governance and direction. -

Media Monitoring Report United Nations Mission in Sudan/ Public Information Office

27 April 2011 Media Monitoring Report www.unmissions.unmis.org United Nations Mission in Sudan/ Public Information Office Post-Referendum Headlines • Gadet prepares for major offensive to free South from SPLA domination (Al-Khartoum) • Commission of inquiry set up on Gabriel Tang and two aides (Al-Sahafa) • Official: Militia leader who clashed with Southern Sudan army surrenders (AP) • Sudan’s president Al-Bashir sacks his security adviser Salah Gosh (ST) • WFP cuts back operations in embattled south Sudan (AFP) • Southern political parties reject constitution (Al-Raed) • We would take the fight to Khartoum - Malik Aggar (Al-Sahafa) • North Sudan’s ruling party risks implosion as internal rifts come into view (ST) • 27,000 southern Sudanese in the open in Khartoum State (Al-Ayyam) Southern Kordofan Elections Focus • President Al-Bashir to visit Al-Mujlad today (Al-Khartoum) • Sudanese president says ready for new war with south (BBC News) Other Headlines • Journalists decide to boycott Foreign Ministry’s activities (Al-Akhbar) NOTE: Reproduction here does not mean that the UNMIS PIO can vouch for the accuracy or veracity of the contents, nor does this report reflect the views of the United Nations Mission in Sudan. Furthermore, international copyright exists on some materials and this summary should not be disseminated beyond the intended list of recipients. Address: UNMIS Headquarters, P.O. Box 69, Ibeid Khatim St, Khartoum 11111, SUDAN Phone: (+249-1) 8708 6000 - Fax: (+249-1) 8708 6200 UNMIS Media Monitoring Report 27 April 2011 Highlights Gadet prepares for major offensive to free South from SPLA domination A l-Khartoum 27/4/11 – rebel leader Peter Gadet has threatened a major offensive to free South Sudan from SPLA domination, saying his soldiers yesterday defeated the force rushed by Juba to retake fallen towns. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION ....................................................... -

Gatluak Gai's Rebellion, Unity State

Gatluak Gai’s Rebellion, Unity State Gatluak Gai’s rebellion is linked to the complex and high-stakes politics of Unity state. The site of horrific violence and significant casualties during the civil war, Unity is home to political dynamics that mirror tensions at the highest levels of the Southern government. Given the ongoing armed banditry and insecurity in the state, these rifts, driven by wartime ties and longstanding tribal alliances, are unlikely to be resolved in the run-up to the South’s independence on 9 July 2011. Although Gatluak was not a major player in state politics prior to the April 2010 elections, the Government of South Sudan (GoSS) was convinced that he was linked to Angelina Teny—wife of Vice-President Riek Machar—who ran as an ‘independent’ candidate for the Unity governorship, and thus perceived him as a threat. Consequently, the GoSS deployed additional Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) troops to the state, particularly in Mayom and Pariang counties (seasonal destinations of the migrating Missiriya) and along the border with South Kordofan. The increased SPLA presence was motivated by suspicions about Angelina’s political aspirations, as well as the army’s intention to neutralize any potential security threats, such as the Missiriya. Oil-rich Unity, which shares a tense and militarized border with North Sudan, is of particular strategic importance to the GoSS. Gatluak and his forces did not launch any attacks in Unity between June and December 2010. Nevertheless, the areas of the state where he initially operated—in and around Koch county, south of Bentiu, and in the centre of the state—continued to be insecure, with frequent incidents of banditry and armed violence. -

Human Security in Sudan: the Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission

Human Security in Sudan: The Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission Prepared for the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ottawa, January 2000 Disclaimer: This report was prepared by Mr. John Harker for the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. The views and opinions contained in this report are not necessarily those of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. 1 Human Security in Sudan: Executive Summary 1 Introduction On October 26, 1999, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lloyd Axworthy and the Minister for International Co-operation, Maria Minna, announced several Canadian initiatives to bolster international efforts backing a negotiated settlement to the 43-year civil war in Sudan, including the announcement of an assessment mission to Sudan to examine allegations about human rights abuses, including the practice of slavery. There are few other parts of the world where human security is so lacking, and where the need for peace and security - precursors to sustainable development - is so pronounced. Canada's commitment to human security, particularly the protection of civilians in armed conflict, provides a clear basis for its involvement in Sudan and its support for the peace process. Charm Offensive, or Signs of Progress? Following the visit to Khartoum of an EU Mission, a political dialogue was launched by the European Union on November 11 1999. The EU was of the view that there has been sufficient progress in Sudan to warrant a renewed dialogue. In this view, there has been a positive change, and it is necessary to encourage the Sudanese, and push them further where there is need. -

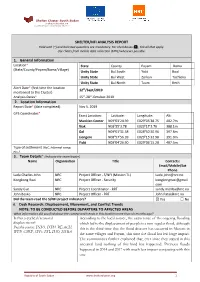

Shelter/Nfi Analysis Report 1

Shelter Cluster South Sudan sheltersouthsudan.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER/NFI ANALYSIS REPORT Field with (*) and italicized questions are mandatory. For checkboxes (☐), tick all that apply. Use charts from mobile data collection (MDC) wherever possible. 1. General Information Location* State County Payam Boma (State/County/Payam/Boma/Village) Unity State Bul South Yidit Bool Unity State Bul West Zorkan Tochloka Unity State Bul North Taam Kech Alert Date* (first time the location 12th/Sept/2019 mentioned to the Cluster) Analysis Dates* 15th-28th-October-2019 2. Location Information Report Date* (date completed) Nov 5, 2019 GPS Coordinates* Exact Location: Latitude: Longitude: Alt: Mankien Center N09003’24.99 E029005’38.75 402.7m Riak N08055’3.78 E029017’3.70 388.1m Gol N09001’31.38 E028050’40.96 397.8m Liengere N08057’56.39 E029015’32.98 391.0m Yidit N09004’26.90 E029006’15.20 407.5m Type of settlement (PoC, informal camp, etc.) 3. Team Details* (Indicate the team leader) Name Organisation Title Contacts: Email/Mobile/Sat Phone Ladu Charles John NRC Project Officer - S/NFI (Mission TL) [email protected] Kongkong Ruei NRC Project Officer - Security kongkongruei@gmail. com Sandy Gur NRC Project Coordinator - RRT [email protected] John Bosko NRC Project Officer - RRT [email protected] Did the team read the S/NFI project indicators? ☒ Yes ☐ No 4. Desk Research: Displacement, Movement, and Conflict Trends NOTE: TO BE CONDUCTED BEFORE DEPARTURE TO AFFECTED AREAS What information did you find about the context and trends in this location more than six months ago? Is this a cyclical/seasonal According to the local source, the occurrence of the ongoing flooding displacement? which led to the displacement of people is a non-regular flood, although Possible sources: INSO, DTM, REACH, this is the third time that the flood disaster has occurred in Mayom in WFP, CSRF, SFPs, FSL IMO, HSBA the same villages and Payam, this time the flood has left huge impact. -

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War”

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War” Africa Report N°221 | 22 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jonglei’s Conflicts Before the Civil War ........................................................................... 3 A. Perpetual Armed Rebellion ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Politics of Inter-Communal Conflict .................................................................. 4 1. The communal is political .................................................................................... 4 2. Mixed messages: Government response to intercommunal violence ................. 7 3. Ethnically-targeted civilian disarmament ........................................................... 8 C. Region over Ethnicity? Shifting Alliances between the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, Greater Bor Dinka and Nuer ...................................................................................... 9 III. South Sudan’s Civil War in Jonglei .................................................................................. 12 A. Armed Factions in Jonglei ........................................................................................ -

Interna Tional Edition

Number 2 2014 ISSN 2196-3940 INTERNATIONAL South Sudan’s Newest War: When Two Old Men Divide a Nation Carlo Koos and Thea Gutschke A political power struggle between South Sudanese president Salva Kiir and former vice president Riek Machar resulted in violent clashes between ethnic army factions in December 2013. Since then fighting has spread across South Sudan and claimed the lives of around 10,000 people. Analysis South Sudan has experienced several insurgencies since gaining independence in 2011. Nevertheless, the current war has the potential to be more destructive to the country than previous ones because both parties – President Salva Kiir, an ethnic Dinka, and his opponent, former vice president Riek Machar, an ethnic Nuer – are instrumentalizing ethnic identities and pulling their communities into their personal feud. A number of latent issues have contributed to the current crisis. These include South Sudan’s dysfunctional political system and inadequate political leadership, the historical distrust between the Dinka and the Nuer, and the country’s unhealthy EDITION dependence on oil rents. The civilian population is carrying the cost of the conflict. More than 10,000 people have been killed and more than one million displaced since the outbreak of the latest violence. Livelihoods have been destroyed and more than 3.7 million people, approximately a third of the population, are estimated to be at risk of food insecurity. The short- and long-term economic consequences for South Sudan are harsh. Oil production has dropped by 40 percent, severely affecting the state’s budget. Trade has suffered. In the long run, political instability will jeopardize foreign direct investment in South Sudan. -

Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014

IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment Report Internally Displaced Persons in Twic County Warrap from Unity State 3 January 2014 Important: - IRNA Report should include secondary data collected by all stakeholders and jointly analyzed - IRNA Report should also include community level assessment analysis by clusters and then jointly analyzed by all stakeholders - Report should adequately cover the de-briefing analysis of assessment team leaders - This report should be produced within two days after the IRNA taking place 1 IRNA Report Twic IDPs from Unity State 3 Jan 2014 Situation Overview (use the secondary information as well as the information gathered under the ‘Generalist’ section of the IRNA questionnaire. Map Drivers of Crisis and underlying factors Place map of affected area if available Conflict has spread across South Sudan following an alleged coup attempt three weeks ago in Juba. Among the states directly affected by the crisis is Unity State which neighbours Warrap State to the East. An influx of Internally Displaced People (IDPs) into Warrap’s Twic County has steadily increased since the last week of December Affected population: 2013. Most of those IDPs have been directly attacked or been caught (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) up in the cross fire during the fighting that has ensued in Unity State, while some have run out of seer fear. Displaced population: (appox. Male/female and boys/girls) Scope of crisis and humanitarian profile Most of the displaced are from Mayom County in Unity State, while 3,215 individuals some have been displaced from as far as Bentiu town the Unity State with possible increase in coming days capital itself, in Rubkona County. -

The War(S) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace

Conflict Research Programme The War(s) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace Flora McCrone in collaboration with the Bridge Network About the Authors Flora McCrone is an independent researcher based in East Africa. She has specialised in research on conflict, armed groups, and political transition across the Horn region for the past nine years. Flora holds a master’s degree in Human Rights from LSE and a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Durham University. The Bridge Network is a group of eight South Sudanese early career researchers based in Nimule, Gogrial, Yambio, Wau, Leer, Mayendit, Abyei, Juba PoC 1, and Malakal. The Bridge Network members are embedded in the communities in which they conduct research. The South Sudanese researchers formed the Bridge Network in November 2017. The team met annually for joint analysis between 2017-2020 in partnership with the Conflict Research Programme. About the Conflict Research Programme The Conflict Research Programme is a four-year research programme hosted by LSE IDEAS, the university’s foreign policy think tank. It is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Our goal is to understand and analyse the nature of contemporary conflict and to identify international interventions that ‘work’ in the sense of reducing violence or contributing more broadly to the security of individuals and communities who experience conflict. © Flora McCrone and the Bridge Network, February 2021. This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.