Gabriel Tang Gatwich Chan ('Tang-Ginye')

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE to SOUTH SUDAN Last Updated 07/31/13

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO SOUTH SUDAN Last Updated 07/31/13 UPPER NILE SUDAN WARRAP ACTED Solidarités ACTED CRS World ABYEI AREA Renk Vision GOAL Food for SOUTH SUDAN CRS SC the Hungry ACTED MENTOR UNITY FAO UNDP GOAL DRC NRC CARE Global Communities/CHF UNFPA Medair IOM UNOPS Mercy Corps GOAL UNICEF MENTOR RI WCDO MENTOR Mercy Corps UNMAS RI World IOM Paloich OCHA WHO Vision SouthSouth Sudan-SudanSudan-Sudan boundaryboundary representsrepresents JanuaryJanuary 1,1, 19561956 alignment;alignment; finalfinal alignmentalignment pendingpending ABYEI AREA * UPPER NILE negotiationsnegotiations andand demarcation.demarcation. Abyei ETHIOPIA Malakal Abanima SOUTH SUDAN-WIDE Bentiu Nagdiar Warawar JONGLEI FAO Agok Yargot ACTED IOM WESTERN BAHR Malualkon NORTHERN UNITY EL GHAZAL Aweil Khorflus Nasir CRS Medair BAHR Pagak WARRAP Food for OCHA Raja EL GHAZAL the Hungry UNICEF Fathay Walgak BAHR EL GHAZAL IMC Akobo WFP Adeso MENTOR Wau WHO Tearfund PACT SOUTH SUDAN JONGLEI UNICEF UMCOR Pochalla World WFP Vision Welthungerhilfe Rumbek ICRC LAKES UNHCR CENTRAL Wulu Mapuordit AFRICAN Akot Bor Domoloto Minkamman REPUBLIC PROGRAM KEY Tambura Amadi USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Kaltok WESTERN EQUATORIA EASTERN EQUATORIA Agriculture and Food Security Livelihoods Juba Kapoeta Economic Recovery and Market Logistics and Relief Commodities Systems Yambio Multi-Sectoral Assistance CENTRAL Education EQUATORIA Torit Nagishot Nutrition EQUATORIA Gender-based Birisi ARC Violence Prevention Protection Ye i CHF Health Risk Management Policy and Practice KENYA -

Power and Proximity: the Politics of State Secession

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Power and Proximity: The Politics of State Secession Elizabeth A. Nelson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1396 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] POWER AND PROXIMITY: THE POLITICS OF STATE SECESSION by ELIZABETH A. NELSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 ELIZABETH A. NELSON All Rights Reserved ii Power and Proximity: The Politics of State Secession by Elizabeth A. Nelson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ ____________________________________ Date Susan L. Woodward Chair of Examining Committee ______________ ____________________________________ Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Professor Susan L. Woodward Professor Peter Liberman Professor Bruce Cronin THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Power and Proximity: The Politics of State Secession by Elizabeth A. Nelson Advisor: Susan L. Woodward State secession is a rare occurrence in the international system. While a number of movements seek secession, the majority fail to achieve statehood. Of the exceptional successes, many have not had the strongest claims to statehood; some of these new states look far less like states than some that have failed. -

South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’S Newest Country

The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Ted Dagne Specialist in African Affairs July 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41900 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Summary In January 2011, South Sudan held a referendum to decide between unity or independence from the central government of Sudan as called for by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that ended the country’s decades-long civil war in 2005. According to the South Sudan Referendum Commission (SSRC), 98.8% of the votes cast were in favor of separation. In February 2011, Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir officially accepted the referendum result, as did the United Nations, the African Union, the European Union, the United States, and other countries. On July 9, 2011, South Sudan is to officially declare its independence. The Obama Administration welcomed the outcome of the referendum and pledged to recognize South Sudan as an independent country in July 2011. The Administration is expected to send a high-level presidential delegation to South Sudan’s independence celebration on July 9, 2011. A new ambassador is also expected to be named to South Sudan. South Sudan faces a number of challenges in the coming years. Relations between Juba, in South Sudan, and Khartoum are poor, and there are a number of unresolved issues between them. The crisis in the disputed area of Abyei remains a contentious issue, despite a temporary agreement reached in mid-June 2011. -

Addis PEACE a 411St ME HEADS O BANJUL, 30 DECEM AFRICAN

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, P.O. Box: 3243 Tel.: (251‐11) 5513 822 Fax: (251‐11) 5519 321 Email: situationroom@africa‐union.org PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL 411st MEETING AT THE LEVEL OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT BANJUL, THE GAMBIA 30 DECEMBER 2013 PSC/AHG/3(CDXI) REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OFF THE COMMISSION ON THE SITUATION IN SOUTH SUDAN PSC/AHG/3(CDXI) Page 1 REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION ON THE SITUATION IN SOUTH SUDAN I. INTRODUCTION 1. The present report is submitted in the context of the meeting of Council to be held in Banjul, The Gambia, on 30 December 2013, to deliberate on the unfolding situation in South Sudan. The conflict in South Sudan erupted on 15 December, in the context of a political challenge to the President of the Republic of South Sudan, from leading members of the ruling party, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). This rapidly mutated into violent confrontation and rebellion. The conflict imperils the lives and wellbeing of South Sudanese, jeopardizes the future of the young nation, and is a threat to regional peace and security. 2. The report provides a background to the current crisis, a chronology of the events of the last six months and an overview of the regional, continental and international response. The report concludes with observations on the way forward. II. BACKGROUND 3. The current conflict represents the accumulation of unresolved political disputes within the leadership of the SPLM. The leaders had disagreements on fundamental aspects of the party and country’s leadership, governance and direction. -

Media Monitoring Report United Nations Mission in Sudan/ Public Information Office

27 April 2011 Media Monitoring Report www.unmissions.unmis.org United Nations Mission in Sudan/ Public Information Office Post-Referendum Headlines • Gadet prepares for major offensive to free South from SPLA domination (Al-Khartoum) • Commission of inquiry set up on Gabriel Tang and two aides (Al-Sahafa) • Official: Militia leader who clashed with Southern Sudan army surrenders (AP) • Sudan’s president Al-Bashir sacks his security adviser Salah Gosh (ST) • WFP cuts back operations in embattled south Sudan (AFP) • Southern political parties reject constitution (Al-Raed) • We would take the fight to Khartoum - Malik Aggar (Al-Sahafa) • North Sudan’s ruling party risks implosion as internal rifts come into view (ST) • 27,000 southern Sudanese in the open in Khartoum State (Al-Ayyam) Southern Kordofan Elections Focus • President Al-Bashir to visit Al-Mujlad today (Al-Khartoum) • Sudanese president says ready for new war with south (BBC News) Other Headlines • Journalists decide to boycott Foreign Ministry’s activities (Al-Akhbar) NOTE: Reproduction here does not mean that the UNMIS PIO can vouch for the accuracy or veracity of the contents, nor does this report reflect the views of the United Nations Mission in Sudan. Furthermore, international copyright exists on some materials and this summary should not be disseminated beyond the intended list of recipients. Address: UNMIS Headquarters, P.O. Box 69, Ibeid Khatim St, Khartoum 11111, SUDAN Phone: (+249-1) 8708 6000 - Fax: (+249-1) 8708 6200 UNMIS Media Monitoring Report 27 April 2011 Highlights Gadet prepares for major offensive to free South from SPLA domination A l-Khartoum 27/4/11 – rebel leader Peter Gadet has threatened a major offensive to free South Sudan from SPLA domination, saying his soldiers yesterday defeated the force rushed by Juba to retake fallen towns. -

Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014

IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment: Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. 0 IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Situation Overview: An ad-hoc IDP camp has been established by the Melut County Commissioner at Dethoma in order to accommodate Dinka IDPs who have fled from Baliet county. Reports of up to 45,000 based in Paloich were initially received by OCHA from RRC and UNMISS staff based in Melut but then subsequent information was received that they had moved to Dethoma. An IRNA mission from Malakal was conducted on 31 January 2014. Due to delays in the deployment by helicopter, the RRC Coordinator was unable to meet the team but we were able to speak to the Deputy Paramount Chief, Chief and a ROSS NGO at the site. The local NGO (Woman Empowerment for Cooperation and Development) had said they had conducted a preliminary registration that showed the presence of 3,075 households. The community leaders said that the camp contained approximately 26,000 individuals. The IRNA team could only visually estimate 5 – 6000 potentially displaced however some may have been absent at the river. The camp is situated on an open field provided and cleared by the Melut County Commissioner, with a river approximately 300metres to the south. There is no cover and as most IDPs had walked to this location, they had carried very minimal NFIs or food. -

Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Worldliness of South Sudan: Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Zachary Mondesire 2018 © Copyright by Zachary Mondesire 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Worldliness of South Sudan: Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba By Zachary Mondesire Master of Art in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Hannah C. Appel, Chair The world’s newest state, South Sudan, became independent in July 2011. In 2013, after the outbreak of the still-ongoing South Sudanese civil war, the UNHCR declared a refugee crisis and continues to document the displacement of millions of South Sudanese citizens. In 2016, Crazy Fox, a popular South Sudanese musician, released a song entitled “Ana Gaid/I am staying.” His song compels us to pay attention to those in South Sudan who have chosen to stay, or to return and still other African regionals from neighboring countries to arrive. The goal of this thesis is to explore the “Crown Lodge,” a hotel in Juba, the capital city of South Sudan, as one such site of arrival, return, and staying put. Paying ethnographic attention to site enables us to think through forms of spatial belonging in and around the hotel that attached racial meaning to national origin and regional identity. ii The thesis of Zachary C. P. Mondesire is approved. Jemima Pierre Aomar Boum Hannah C. Appel, Committee Chair University -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

RVI Local Peace Processes in Sudan.Pdf

Rift Valley Institute ﻤﻌﻬﺪ اﻷﺨدود اﻟﻌﻇﻴم Taasisi ya Bonde Kuu ySMU vlˆ yU¬T tí Machadka Dooxada Rift 东非大裂谷研究院 Institut de la Vallée du Rift Local Peace Processes in Sudan A BASELINE STUDY Mark Bradbury John Ryle Michael Medley Kwesi Sansculotte-Greenidge Commissioned by the UK Government Department for International Development “Our sons are deceiving us... … Our soldiers are confusing us” Chief Gaga Riak Machar at Wunlit Dinka-Nuer Reconciliation Conference 1999 “You, translators, take my words... It seems we are deviating from our agenda. What I expected was that the Chiefs of our land, Dinka and Nuer, would sit on one side and address our grievances against the soldiers. I differ from previous speakers… I believe this is not like a traditional war using spears. In my view, our discussion should not concentrate on the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer, but on the soldiers, who are the ones who are responsible for beginning this conflict. “When John Garang and Riek Machar [leaders of rival SPLA factions] began fighting did we understand the reasons for their fighting? When people went to Bilpam [in Ethiopia] to get arms, we thought they would fight against the Government. We were not expecting to fight against ourselves. I would like to ask Commanders Salva Mathok & Salva Kiir & Commander Parjak [Senior SPLA Commanders] if they have concluded the fight against each other. I would ask if they have ended their conflict. Only then would we begin discussions between the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer. “The soldiers are like snakes. When a snake comes to your house day after day, one day he will bite you. -

Project Proposal

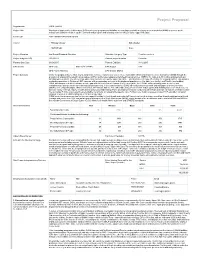

Project Proposal Organization GOAL (GOAL) Project Title Provision of treatment to children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) for children aged 659 month and pregnant and lactating women in Melut County, Upper Nile State Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/N/INGO/526 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster NUTRITION None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 150,000.01 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73049/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary Under the proposed intervention, GOAL will provide curative responses to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) through the provision of outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTPs) and targeted supplementary feeding programmes (TSFPs) for children 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW). The intervention will be targeted to Melut County, Upper Nile State – which has been heavily affected by the ongoing conflict. This includes continuing operations in Dethoma II IDP camp as well as expanding services to the displaced populations in Kor Adar (one facility) and Paloich (two facilities). GOAL also proposes to fill the nutrition service gap in Melut Protection of Civilians (PoC) camp. In the PoC, GOAL will be providing static services, with complementary primary health care and nutrition programming. In the same locations, GOAL will conduct mass outreach and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening campaigns within communities, IDP camps, and the PoC with children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) in order to increase facility referrals. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION .......................................................