A Fractious Rebellion: Inside the SPLM-IO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNMISS “Protection of Civilians” (Poc) Sites

UNMISS “Protection of Civilians” (PoC) Sites As of 9 April, the estimated number of civilians seeking safety in six Protection of Civilians (PoC) sites located on UNMISS bases is 117,604 including 52,908 in Bentiu, 34,420 in Juba UN House, 26,596 in Malakal, 2,374 in Bor, 944 in Melut and 362 in Wau. Number of civilians seeking protection STATE LOCATION Central UN House PoC I, II and III 34,420 Equatoria Juba Jonglei Bor 2,374 Upper Nile Malakal 26,596 Melut 944 Unity Bentiu 52,908 Western Bahr Wau 362 El Ghazal TOTAL 117,604 Activities in Protection Sites Juba, UN House The refugee agency in collaboration with the South Sudanese Commission for Refugee Affairs will be looking into issuing Asylum seeker certificates to around 500 foreign nationals at UN House PoC Site from 9 to 15 April. ADDITIONAL LINKS CLICK THE LINKS WEBSITE UNMISS accommodating 4,500 new IDPS in Malakal http://bit.ly/1JD4C4E Children immunized against measles in Bentiu http://bit.ly/1O63Ain Education needs peace, UNICEF Ambassador says in Yambio http://bit.ly/1CH51wX Food coming through Sudan helping hundreds of thousands http://bit.ly/1FBHHmw PHOTO UN Photo http://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/627/0627829.html http://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/627/0627828.html http://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/627/0627831.html UNMISS facebook albums: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.817801171628889.1073742395.160839527325060&type=3 https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.818162894926050.1073742396.160839527325060&type=3 UNMISS flickr album: -

EOI Mission Template

United Nations Nations Unies United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) South Sudan REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION OF INTEREST (EOI) This notice is placed on behalf of UNMISS. United Nations Procurement Division (UNPD) cannot provide any warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of contents of furnished information; and is unable to answer any enquiries regarding this EOI. You are therefore requested to direct all your queries to United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) using the fax number or e-mail address provided below. Title of the EOI: Provision of Refrigerant Gases to UNMISS in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan Date of this EOI: 10 January 2020 Closing Date for Receipt of EOI: 11 February 2020 EOI Number: EOIUNMISS17098 Chief Procurement Officer Unmiss Hq, Tomping Site Near Juba Address EOI response by fax or e-mail to the Attention of: International Airport, Room No 3c/02 Juba, Republic Of South Sudan Fax Number: N/A E-mail Address: [email protected], [email protected] UNSPSC Code: 24131513 DESCRIPTION OF REQUIREMENTS PD/EOI/MISSION v2018-01 1. The United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) has a requirement for the provision of Refrigerant Gases in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan and hereby solicits Expression of Interest (EOI) from qualified and interested vendors. SPECIFIC REQUIREMENTS / INFORMATION (IF ANY) Conditions: 2. Interested service providers/companies are invited to submit their EOIs for consideration by email (preferred), courier or by hand delivery as indicated below. -

Power and Proximity: the Politics of State Secession

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Power and Proximity: The Politics of State Secession Elizabeth A. Nelson The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1396 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] POWER AND PROXIMITY: THE POLITICS OF STATE SECESSION by ELIZABETH A. NELSON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 ELIZABETH A. NELSON All Rights Reserved ii Power and Proximity: The Politics of State Secession by Elizabeth A. Nelson This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ ____________________________________ Date Susan L. Woodward Chair of Examining Committee ______________ ____________________________________ Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Professor Susan L. Woodward Professor Peter Liberman Professor Bruce Cronin THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Power and Proximity: The Politics of State Secession by Elizabeth A. Nelson Advisor: Susan L. Woodward State secession is a rare occurrence in the international system. While a number of movements seek secession, the majority fail to achieve statehood. Of the exceptional successes, many have not had the strongest claims to statehood; some of these new states look far less like states than some that have failed. -

Central African Republic (C.A.R.) Appears to Have Been Settled Territory of Chad

Grids & Datums CENTRAL AFRI C AN REPUBLI C by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The Central African Republic (C.A.R.) appears to have been settled territory of Chad. Two years later the territory of Ubangi-Shari and from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the the military territory of Chad were merged into a single territory. The Kanem-Bornou, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based in Lake colony of Ubangi-Shari - Chad was formed in 1906 with Chad under Chad and the Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present- a regional commander at Fort-Lamy subordinate to Ubangi-Shari. The day C.A.R., using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from commissioner general of French Congo was raised to the status of a which slaves were traded north across the Sahara and to West Africa governor generalship in 1908; and by a decree of January 15, 1910, for export by European traders. Population migration in the 18th and the name of French Equatorial Africa was given to a federation of the 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, three colonies (Gabon, Middle Congo, and Ubangi-Shari - Chad), each Banda, and M’Baka-Mandjia. In 1875 the Egyptian sultan Rabah of which had its own lieutenant governor. In 1914 Chad was detached governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day C.A.R.” (U.S. from the colony of Ubangi-Shari and made a separate territory; full Department of State Background Notes, 2012). colonial status was conferred on Chad in 1920. -

Media Monitoring Report United Nations Mission in Sudan/ Public Information Office

27 April 2011 Media Monitoring Report www.unmissions.unmis.org United Nations Mission in Sudan/ Public Information Office Post-Referendum Headlines • Gadet prepares for major offensive to free South from SPLA domination (Al-Khartoum) • Commission of inquiry set up on Gabriel Tang and two aides (Al-Sahafa) • Official: Militia leader who clashed with Southern Sudan army surrenders (AP) • Sudan’s president Al-Bashir sacks his security adviser Salah Gosh (ST) • WFP cuts back operations in embattled south Sudan (AFP) • Southern political parties reject constitution (Al-Raed) • We would take the fight to Khartoum - Malik Aggar (Al-Sahafa) • North Sudan’s ruling party risks implosion as internal rifts come into view (ST) • 27,000 southern Sudanese in the open in Khartoum State (Al-Ayyam) Southern Kordofan Elections Focus • President Al-Bashir to visit Al-Mujlad today (Al-Khartoum) • Sudanese president says ready for new war with south (BBC News) Other Headlines • Journalists decide to boycott Foreign Ministry’s activities (Al-Akhbar) NOTE: Reproduction here does not mean that the UNMIS PIO can vouch for the accuracy or veracity of the contents, nor does this report reflect the views of the United Nations Mission in Sudan. Furthermore, international copyright exists on some materials and this summary should not be disseminated beyond the intended list of recipients. Address: UNMIS Headquarters, P.O. Box 69, Ibeid Khatim St, Khartoum 11111, SUDAN Phone: (+249-1) 8708 6000 - Fax: (+249-1) 8708 6200 UNMIS Media Monitoring Report 27 April 2011 Highlights Gadet prepares for major offensive to free South from SPLA domination A l-Khartoum 27/4/11 – rebel leader Peter Gadet has threatened a major offensive to free South Sudan from SPLA domination, saying his soldiers yesterday defeated the force rushed by Juba to retake fallen towns. -

Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Worldliness of South Sudan: Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Zachary Mondesire 2018 © Copyright by Zachary Mondesire 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Worldliness of South Sudan: Space, Home and Racial Meaning Making in Post Independence Juba By Zachary Mondesire Master of Art in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Hannah C. Appel, Chair The world’s newest state, South Sudan, became independent in July 2011. In 2013, after the outbreak of the still-ongoing South Sudanese civil war, the UNHCR declared a refugee crisis and continues to document the displacement of millions of South Sudanese citizens. In 2016, Crazy Fox, a popular South Sudanese musician, released a song entitled “Ana Gaid/I am staying.” His song compels us to pay attention to those in South Sudan who have chosen to stay, or to return and still other African regionals from neighboring countries to arrive. The goal of this thesis is to explore the “Crown Lodge,” a hotel in Juba, the capital city of South Sudan, as one such site of arrival, return, and staying put. Paying ethnographic attention to site enables us to think through forms of spatial belonging in and around the hotel that attached racial meaning to national origin and regional identity. ii The thesis of Zachary C. P. Mondesire is approved. Jemima Pierre Aomar Boum Hannah C. Appel, Committee Chair University -

RVI Local Peace Processes in Sudan.Pdf

Rift Valley Institute ﻤﻌﻬﺪ اﻷﺨدود اﻟﻌﻇﻴم Taasisi ya Bonde Kuu ySMU vlˆ yU¬T tí Machadka Dooxada Rift 东非大裂谷研究院 Institut de la Vallée du Rift Local Peace Processes in Sudan A BASELINE STUDY Mark Bradbury John Ryle Michael Medley Kwesi Sansculotte-Greenidge Commissioned by the UK Government Department for International Development “Our sons are deceiving us... … Our soldiers are confusing us” Chief Gaga Riak Machar at Wunlit Dinka-Nuer Reconciliation Conference 1999 “You, translators, take my words... It seems we are deviating from our agenda. What I expected was that the Chiefs of our land, Dinka and Nuer, would sit on one side and address our grievances against the soldiers. I differ from previous speakers… I believe this is not like a traditional war using spears. In my view, our discussion should not concentrate on the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer, but on the soldiers, who are the ones who are responsible for beginning this conflict. “When John Garang and Riek Machar [leaders of rival SPLA factions] began fighting did we understand the reasons for their fighting? When people went to Bilpam [in Ethiopia] to get arms, we thought they would fight against the Government. We were not expecting to fight against ourselves. I would like to ask Commanders Salva Mathok & Salva Kiir & Commander Parjak [Senior SPLA Commanders] if they have concluded the fight against each other. I would ask if they have ended their conflict. Only then would we begin discussions between the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer. “The soldiers are like snakes. When a snake comes to your house day after day, one day he will bite you. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Gatluak Gai's Rebellion, Unity State

Gatluak Gai’s Rebellion, Unity State Gatluak Gai’s rebellion is linked to the complex and high-stakes politics of Unity state. The site of horrific violence and significant casualties during the civil war, Unity is home to political dynamics that mirror tensions at the highest levels of the Southern government. Given the ongoing armed banditry and insecurity in the state, these rifts, driven by wartime ties and longstanding tribal alliances, are unlikely to be resolved in the run-up to the South’s independence on 9 July 2011. Although Gatluak was not a major player in state politics prior to the April 2010 elections, the Government of South Sudan (GoSS) was convinced that he was linked to Angelina Teny—wife of Vice-President Riek Machar—who ran as an ‘independent’ candidate for the Unity governorship, and thus perceived him as a threat. Consequently, the GoSS deployed additional Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) troops to the state, particularly in Mayom and Pariang counties (seasonal destinations of the migrating Missiriya) and along the border with South Kordofan. The increased SPLA presence was motivated by suspicions about Angelina’s political aspirations, as well as the army’s intention to neutralize any potential security threats, such as the Missiriya. Oil-rich Unity, which shares a tense and militarized border with North Sudan, is of particular strategic importance to the GoSS. Gatluak and his forces did not launch any attacks in Unity between June and December 2010. Nevertheless, the areas of the state where he initially operated—in and around Koch county, south of Bentiu, and in the centre of the state—continued to be insecure, with frequent incidents of banditry and armed violence. -

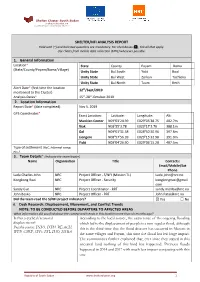

Shelter/Nfi Analysis Report 1

Shelter Cluster South Sudan sheltersouthsudan.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER/NFI ANALYSIS REPORT Field with (*) and italicized questions are mandatory. For checkboxes (☐), tick all that apply. Use charts from mobile data collection (MDC) wherever possible. 1. General Information Location* State County Payam Boma (State/County/Payam/Boma/Village) Unity State Bul South Yidit Bool Unity State Bul West Zorkan Tochloka Unity State Bul North Taam Kech Alert Date* (first time the location 12th/Sept/2019 mentioned to the Cluster) Analysis Dates* 15th-28th-October-2019 2. Location Information Report Date* (date completed) Nov 5, 2019 GPS Coordinates* Exact Location: Latitude: Longitude: Alt: Mankien Center N09003’24.99 E029005’38.75 402.7m Riak N08055’3.78 E029017’3.70 388.1m Gol N09001’31.38 E028050’40.96 397.8m Liengere N08057’56.39 E029015’32.98 391.0m Yidit N09004’26.90 E029006’15.20 407.5m Type of settlement (PoC, informal camp, etc.) 3. Team Details* (Indicate the team leader) Name Organisation Title Contacts: Email/Mobile/Sat Phone Ladu Charles John NRC Project Officer - S/NFI (Mission TL) [email protected] Kongkong Ruei NRC Project Officer - Security kongkongruei@gmail. com Sandy Gur NRC Project Coordinator - RRT [email protected] John Bosko NRC Project Officer - RRT [email protected] Did the team read the S/NFI project indicators? ☒ Yes ☐ No 4. Desk Research: Displacement, Movement, and Conflict Trends NOTE: TO BE CONDUCTED BEFORE DEPARTURE TO AFFECTED AREAS What information did you find about the context and trends in this location more than six months ago? Is this a cyclical/seasonal According to the local source, the occurrence of the ongoing flooding displacement? which led to the displacement of people is a non-regular flood, although Possible sources: INSO, DTM, REACH, this is the third time that the flood disaster has occurred in Mayom in WFP, CSRF, SFPs, FSL IMO, HSBA the same villages and Payam, this time the flood has left huge impact.