EE Final Daniel Gordon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joachim Raff Symphony No

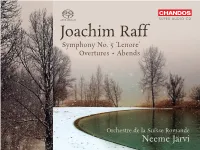

SUPER AUDIO CD Joachim Raff Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ Overtures • Abends Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Neeme Järvi © Mary Evans Picture Library Picture © Mary Evans Joachim Raff Joachim Raff (1822 – 1882) 1 Overture to ‘Dame Kobold’, Op. 154 (1869) 6:48 Comic Opera in Three Acts Allegro – Andante – Tempo I – Poco più mosso 2 Abends, Op. 163b (1874) 5:21 Rhapsody Orchestration by the composer of the fifth movement from Piano Suite No. 6, Op. 163 (1871) Moderato – Un poco agitato – Tempo I 3 Overture to ‘König Alfred’, WoO 14 (1848 – 49) 13:43 Grand Heroic Opera in Four Acts Andante maestoso – Doppio movimento, Allegro – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto, quasi Tempo I – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto – Andante maestoso 4 Prelude to ‘Dornröschen’, WoO 19 (1855) 6:06 Fairy Tale Epic in Four Parts Mäßig bewegt 5 Overture to ‘Die Eifersüchtigen’, WoO 54 (1881 – 82) 8:25 Comic Opera in Three Acts Andante – Allegro 3 Symphony No. 5, Op. 177 ‘Lenore’ (1872) 39:53 in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur Erste Abtheilung. Liebesglück (First Section. Joy of Love) 6 Allegro 10:29 7 Andante quasi Larghetto 8:04 Zweite Abtheilung. Trennung (Second Section. Separation) 8 Marsch-Tempo – Agitato 9:13 Dritte Abtheilung. Wiedervereinigung im Tode (Third Section. Reunion in Death) 9 Introduction und Ballade (nach G. Bürger’s ‘Lenore’). Allegro – Un poco più mosso (quasi stretto) 11:53 TT 80:55 Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Bogdan Zvoristeanu concert master Neeme Järvi 4 Raff: Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ / Overtures / Abends Symphony No. 5 in E major, Op. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

Raff's Arragement for Piano of Bach's Cello Suites

Six Sonatas for Cello by J.S.Bach arranged for the Pianoforte by JOACHIM RAFF WoO.30 Sonata No.1 in G major Sonate No.2 in D minor Sonate No.3 in C major Sonate No.4 in E flat major Sonate No.5 in C minor Sonate No.6 in D major Joachim Raff’s interest in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and the inspiration he drew from them is unmatched by any of the other major composers in the second half of the 19th century. One could speculate that Raff’s partiality for polyphonic writing originates from his studies of Bach’s works - the identification of “influenced by Bach” with “Polyphony” is a popular idea but is often questionable in terms of scientific correctness. Raff wrote numerous original compositions in polyphonic style and used musical forms of the baroque period. However, he also created a relatively large number of arrangements and transcriptions of works by Bach. Obviously, Bach’s music exerted a strong attraction on Raff that went further than plain admiration. Looking at Raff’s arrangements one can easily detect his particular interest in those works by Bach that could be supplemented by another composer. Upon these models Raff could fit his reverence for the musical past as well as exploit his never tiring interest in the technical aspects of the art of composition. One of the few statements we have by Raff about the basics of his art reveal his concept of how to attach supplements to works by Bach. Raff wrote about his orchestral arrangement of Bach’s Ciaconna in d minor for solo violin: "Everybody who has studied J.S. -

A Structural Analysis of the Relationship Between Programme, Harmony and Form in the Symphonic Poems of Franz Liszt Keith Thomas Johns University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 A structural analysis of the relationship between programme, harmony and form in the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt Keith Thomas Johns University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Johns, Keith Thomas, A structural analysis of the relationship between programme, harmony and form in the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1927 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PROGRAMME, HARMONY AND FORM IN THE SYMPHONIC POEMS OF FRANZ LISZT. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from THE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by KEITH THOMAS JOHNS (M.Litt.,B.A.Hons.,Grad.Dip.Ed., F.L.C.M., F.T.C.L., L.T.C.L. ) SCHOOL OF CREATIVE ARTS 1986 i ABSTRACT This thesis examines the central concern in an analysis of the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt, that is, the relationship between programme,harmony and form. In order to make a thorough and clear analysis of this relationship a structural/semiotic analysis has been developed as the analysis of best fit. Historically it has been fashionable to see Liszt's symphonic poems in terms of sonata form or a form only making sense in terms of the attached programme. Both of these ideas are critically examined in this analysis. -

Neeme Järvi Highlights from a Remarkable 30-Year Recording Career Neeme Järvi Järvi Neeme

NEEME JÄRVI Highlights from a remarkable 30-year recording career Neeme Järvi © Tiit Veermäe / Alamy Neeme Järvi (b. 1937) Highlights from a remarkable 30-year recording career COMPACT DISC ONE Antonín Dvořák (1841 – 1904) 1 Carnival, Op. 92 (B 169) 9:04 Concert Overture Scottish National Orchestra (CHAN 9002 – download only) Johan Halvorsen (1864 – 1935) 2 La Mélancolie 2:27 Mélodie de Ole Bull (1810 – 1880) Melina Mandozzi violin Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra (CHAN 10584) Antonín Dvořák 3 Slavonic Dance in E minor, Op. 72 (B 147) No. 2 5:30 Second Series Scottish National Orchestra (CHAN 6641) 3 Gustav Mahler (1860 – 1911) 4 Nun seh’ ich wohl, warum so dunkle Flammen 4:52 No. 2 from Kindertotenlieder Linda Finnie mezzo-soprano Scottish National Orchestra (CHAN 9545 – download only) Franz von Suppé (1819 – 1895) 5 March from ‘Fatinitza’ 2:26 Royal Scottish National Orchestra (not previously released) Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897) 6 Hungarian Dance No. 19 in B minor 2:23 Orchestrated by Antonín Dvořák London Symphony Orchestra (CHAN 10073 X) Ferruccio Busoni (1866 – 1924) 7 Finale from ‘Tanzwalzer’, Op. 53 4:03 BBC Philharmonic (CHAN 9920) 4 Giovanni Bolzoni (1841 – 1919) 8 Minuetto 3:58 Detroit Symphony Orchestra (CHAN 6648) Zoltán Kodály (1882 – 1967) 9 Intermezzo from ‘Háry János Suite’ 5:03 Laurence Kaptain cimbalom Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CHAN 8877) Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937) 10 La Valse 12:07 Poème chorégraphique pour orchestre Detroit Symphony Orchestra (CHAN 6615) Johann Severin Svendsen (1840 – 1911) 11 Träume 3:45 Studie zu Tristan und Isolde Arrangement of No. 5 from Fünf Gedichte für eine Frauenstimme (‘Wesendonck Lieder’) by Richard Wagner Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra (CHAN 10693) 5 Richard Strauss (1864 – 1949) 12 Morgen! 4:03 No. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2005

anglewood - ORIGINS GAU€RV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 i^^H^H^H^m Wfi? Burning Tree Estates! " ^fWf —-r- m& II •HI I^Sror HI! an inviting opportunity in the Berkshires: our exclusive community of fifteen [ Comforts of Home ] tastefully unique homes. Classic New duality of Life ] England designs, abundant with luxury [ 5rai"<? of Community ] amenities, are built with the discerning homeowner in mind. Each is majestically sited on private wooded acres along tranquil streets. Please schedule an appointment to explore our distinctive designs and the remaining lots available at Burning Tree Estates. For more information please call lli|-{Si4~3 or visit Burning Tree Road BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA One Hundred and Twenty- Fourth Season, 2004-05 TANGLEWOOD 2005 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman John F. Cogan, Jr., Vice-Chairman Robert P. O'Block, Vice-Chairman Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman Edward Linde, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Harlan E. Anderson Eric D. Collins Edmund Kelly Edward I. Rudman George D. Behrakis Diddy Cullinane, George Krupp Hannah H. Schneider Gabriella Beranek ex-officio R. Willis Leith, Jr. Thomas G. Sternberg Mark G. Borden William R. Elfers Nathan R. Miller Stephen R. Weber Jan Brett Nancy J. Fitzpatrick Richard P. Morse Stephen R. Weiner Samuel B. Bruskin Charles K. Gifford Ann M. Philbin, Robert C. Winters Paul Buttenwieser Thelma E. Goldbere James F. Cleary Life Trustees Vernon R. -

Current Review

Current Review Franz Liszt: Künstlerfestzug - Tasso - Dante Symphony aud 97.760 EAN: 4022143977601 4022143977601 Fanfare (2020.05.01) Franz Liszt’s purely symphonic works, viewed in hindsight, have been more historically instructive than popular with the public. Only A Faust Symphony and Les préludes ever entered the general repertoire, and the latter is currently on life support, though, in fairness, this is probably due to over-familiarity from film, television, and Muzak at the supermarket. Although Liszt sowed the seeds of modern development in concert music, from tone poems to tone rows, his orchestral pieces sound melodramatically pianistic to most ears, constantly declaiming in octaves to stir up excitement and—kiss of death—rarely featuring inspired melodies. An exception is the “Gretchen” movement from his Faust Symphony, which Liszt realized was destined for popularity and published separately in various permutations. Liszt also had trouble with orchestration. Indeed, much of what we encounter was actually scored by Joachim Raff, though musicologists today easily demonstrate that Raff took too much credit as a collaborator, when in fact he simply orchestrated Liszt’s direct intentions. Scholars of the day twisted themselves into pretzels worrying whether Liszt’s 1857 Dante Symphony, omitting “Paradiso,” correctly represented Dante Alighieri’s 14th-century epic poem, “Divine Comedy.” Wagner, horrified at Liszt’s original decision to conclude the piece with a depiction—presumably loud and bombastic—of paradise, urged him to keep the music ethereal. Liszt took Wagner’s critique to heart, and the symphony finishes with a women’s chorus singing Mary’s hymn of praise from the Gospel according to St. -

NFA 2021 Program Book Concert Programs 8 3 21

THURSDAY Annual Meeting and Opening Flute Orchestra Concert Thursday, August 12, 2021 9:00–10:00 AM CDT Adah Toland Jones, conductor Kathy Farmer, coordinator Valse, from Sleeping Beauty Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–93) Out of the Chaos of My Doubt Gordon Jones (b. 1947) Interlude No. 1 Rêverie Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Out of the Chaos of My Doubt Gordon Jones (b. 1947) Interlude No. 2 Talisman Alexandra Molnar-Suhajda (b. 1975) Out of the Chaos of My Doubt Gordon Jones (b. 1947) Interlude No. 3 Sierra Morning Freedom Jonathan Cohen (b. 1954) 2. Peregrine Bugler’s Dream Leo Arnaud (1904–91) 7 Decades of Innovating the Imagined: Celebrating the Music of Robert Dick Thursday, August 12, 2021 10:00–11:00 AM CDT Flames Must Not Encircle Sides Robert Dick (b. 1950) Lisa Bost-Sandberg Afterlight Dick Bonnie McAlvin Fire's Bird Dick Mary Kay Fink Book of Shadows Dick Leonard Garrison, bass flute Time is a Two Way Street Dick I. II. Robert Dick and Melissa Keeling High School Soloist Competition Final Round: Part I Thursday, August 12, 2021 10:00–11:30 AM CDT Amy I-Yun Tu, coordinator Katie Leung, piano Recorded round judges: Brian Dunbar, Luke Fitzpatrick, Izumi Miyahara Final round judges: Julietta Curenton, Eric Lamb, Susan Milan, Daniel Velasco, Laurel Zucker Finalists in alphabetical order: Emily DeNucci Joanna Hsieh Choyi Lee Xiaoxi Li Finalists will perform the following works in the order of their choosing: For Each Inch Cut Andrew Rodriguez (b. 1989) World Premiere Valse Caprice Daniel S. Wood (1872–1927) Sonata Francis Poulenc (1899–1963) 1. -

SWR2 Musikstunde Raffsche Raritäten Zum Leben Des

SWR2 Musikstunde Raffsche Raritäten - Zum Leben des Komponisten Joachim Raff (2) Von Jörg Lengersdorf Sendung: 16. Juni 2020 9.05 Uhr Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2017 SWR2 können Sie auch im SWR2 Webradio unter www.SWR2.de und auf Mobilgeräten in der SWR2 App hören – oder als Podcast nachhören: Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2- Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de Die SWR2 App für Android und iOS Hören Sie das SWR2 Programm, wann und wo Sie wollen. Jederzeit live oder zeitversetzt, online oder offline. Alle Sendung stehen mindestens sieben Tage lang zum Nachhören bereit. Nutzen Sie die neuen Funktionen der SWR2 App: abonnieren, offline hören, stöbern, meistgehört, Themenbereiche, Empfehlungen, Entdeckungen … Kostenlos herunterladen: www.swr2.de/app SWR2 Musikstunde mit Jörg Lengersdorf 15. Juni 2020 – 19. Juni 2020 „Joachim Raff“ Ein ganz eigener Kopf (2) Nachdem der 23jährige Joachim Raff 1845 wohl in zwei Tagen die 80 Kilometer von Zürich nach Basel im Regen zu Fuß zurückgelegt hat, zwischendurch kurz in einer Herberge eingenickt ist, und nur in allerletzter Sekunde zum Konzert von Franz Liszt kommt, scheint es Franz Liszt, den so hartnäckig verehrten, tatsächlich zu rühren. „Der Dämon, der mich mein ganzes Leben lang verfolgt, hatte damals alle Schleusen des Himmels geöffnet, um die Wege vor mir schlammig, die Luft schwer und feucht und das Tageslicht trüber und kürzer zu machen. -

JS Bach's Chaconne in D Minor

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1991 J. S. Bach's Chaconne in D Minor: An Examination of Three Arrangements for Piano Solo. Jeffery Mark Pruett Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pruett, Jeffery Mark, "J. S. Bach's Chaconne in D Minor: An Examination of Three Arrangements for Piano Solo." (1991). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5142. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5142 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original,beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from leftlo right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The integration of lyricism into the symphonies of Mahler: a selective analytical study of the structural impact of the lyric voice Lewis, Alexander James Ashton How to cite: Lewis, Alexander James Ashton (1999) The integration of lyricism into the symphonies of Mahler: a selective analytical study of the structural impact of the lyric voice, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4397/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract The Integration of Lyricism into the Symphonies of Mahler. A selective analytical study of the structural impact of the lyric voice. by Alexander James Ashton Lewis This study develops a critical analysis of the first movements of Gustav Mahler's V\ 2' nd and 9* Symphonies, with the intention of illuminating the nature of the lyric voice's interaction with the necessary structural conditions of a symphonic first movement. -

(Re)Constructing Johann Sebastian Bach: Reception History and Performance Practice in New York City During

(RE)CONSTRUCTING JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH: RECEPTION HISTORY AND PERFORMANCE PRACTICE IN NEW YORK CITY DURING THE GREAT WAR A THESIS IN Musicology Presented to the faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC By THOMAS JARED MARKS B.M. University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2010 Kansas City, Missouri 2013 ©2013 THOMAS JARED MARKS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED (RE)CONSTRUCTING JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH: RECEPTION HISTORY AND PERFORMANCE PRACTICE IN NEW YORK CITY DURING THE GREAT WAR Thomas Jared Marks, Candidate for the Master of Music Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2013 ABSTRACT The perception of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) in New York City during the time of the Great War can be illuminated through two threads: 1) reception history and reputation, and 2) contemporary performance practices. Between 1914 and 1927, the reputation of Bach migrated away from one having nationalistic and Romantic associations to one embodying both a “universal” objectivity and a distinctly American subjectivity. Similarly, the manner in which Bach’s music was performed also changed. Before the Great War, transcribing and arranging Bach’s music was common. After the war, some New York City critics began to advocate for Bach’s music to be played as historical reconstructions. Transcriptions and arrangements continued to be performed alongside historical reconstructions, and both a subjective and historically “objective” approaches to performing the composer’s music existed. New York City musician William Henry Humiston (1869-1923) and his idea of Bach provides a useful case study of one musician’s approach to understanding the composer.