A Structural Analysis of the Relationship Between Programme, Harmony and Form in the Symphonic Poems of Franz Liszt Keith Thomas Johns University of Wollongong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

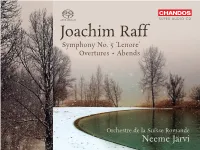

Joachim Raff Symphony No

SUPER AUDIO CD Joachim Raff Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ Overtures • Abends Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Neeme Järvi © Mary Evans Picture Library Picture © Mary Evans Joachim Raff Joachim Raff (1822 – 1882) 1 Overture to ‘Dame Kobold’, Op. 154 (1869) 6:48 Comic Opera in Three Acts Allegro – Andante – Tempo I – Poco più mosso 2 Abends, Op. 163b (1874) 5:21 Rhapsody Orchestration by the composer of the fifth movement from Piano Suite No. 6, Op. 163 (1871) Moderato – Un poco agitato – Tempo I 3 Overture to ‘König Alfred’, WoO 14 (1848 – 49) 13:43 Grand Heroic Opera in Four Acts Andante maestoso – Doppio movimento, Allegro – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto, quasi Tempo I – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto – Andante maestoso 4 Prelude to ‘Dornröschen’, WoO 19 (1855) 6:06 Fairy Tale Epic in Four Parts Mäßig bewegt 5 Overture to ‘Die Eifersüchtigen’, WoO 54 (1881 – 82) 8:25 Comic Opera in Three Acts Andante – Allegro 3 Symphony No. 5, Op. 177 ‘Lenore’ (1872) 39:53 in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur Erste Abtheilung. Liebesglück (First Section. Joy of Love) 6 Allegro 10:29 7 Andante quasi Larghetto 8:04 Zweite Abtheilung. Trennung (Second Section. Separation) 8 Marsch-Tempo – Agitato 9:13 Dritte Abtheilung. Wiedervereinigung im Tode (Third Section. Reunion in Death) 9 Introduction und Ballade (nach G. Bürger’s ‘Lenore’). Allegro – Un poco più mosso (quasi stretto) 11:53 TT 80:55 Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Bogdan Zvoristeanu concert master Neeme Järvi 4 Raff: Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ / Overtures / Abends Symphony No. 5 in E major, Op. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Qt7q1594xs.Pdf

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title A Critical Inferno? Hoplit, Hanslick and Liszt's Dante Symphony Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7q1594xs Author Grimes, Nicole Publication Date 2021-06-28 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A Critical Inferno? Hoplit, Hanslick and Liszt’s Dante Symphony NICOLE GRIMES ‘Wie ist in der Musik beseelte Form von leerer Form wissenschaftlich zu unterscheiden?’1 Introduction In 1881, Eduard Hanslick, one of the most influential music critics of the nineteenth century, published a review of a performance of Liszt’s Dante Symphony (Eine Sym- phonie zu Dantes Divina commedia) played at Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde on 14 April, the eve of Good Friday.2 Although he professed to be an ‘admirer of Liszt’, Hanslick admitted at the outset that he was ‘not a fan of his compositions, least of all his symphonic poems’. Having often given his opinion in detail on those works in the Neue Freie Presse, Hanslick promised brevity on this occasion, asserting that ‘Liszt wishes to compose with poetic elements rather than musical ones’. There is a deep genesis to Hanslick’s criticism of Liszt’s compositions, one that goes back some thirty years to the controversy surrounding progress in music and musical aesthetics that took place in the Austro-German musical press between the so-called ‘New Germans’ and the ‘formalists’ in the 1850s. This controversy was bound up not only with music, but with the philosophical positions the various parties held. The debate was concerned with issues addressed in Hanslick’s monograph Vom Musika- lisch-Schönen, first published in 1854,3 and with opinions expressed by Liszt in a series of three review articles on programme music published contemporaneously in the 1 ‘How is form imbued with meaning to be differentiated philosophically from empty form?’ Eduard Hanslick, Aus meinem Leben, ed. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

The Hungarian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and Ideological Parallels Between Liszt and Bartók David Hill

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Spring 2015 The unH garian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and ideological parallels between Liszt and Bartók David B. Hill James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Hill, David B., "The unH garian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and ideological parallels between Liszt and Bartók" (2015). Dissertations. 38. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/38 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Hungarian Rhapsodies and the 15 Hungarian Peasant Songs: Historical and Ideological Parallels Between Liszt and Bartók David Hill A document submitted to the graduate faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music May 2015 ! TABLE!OF!CONTENTS! ! Figures…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…iii! ! Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...iv! ! Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………...1! ! PART!I:!SIMILARITIES!SHARED!BY!THE!TWO!NATIONLISTIC!COMPOSERS! ! A.!Origins…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4! ! B.!Ties!to!Hungary…………………………………………………………………………………………...…..9! -

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

Orfeo Euridice

ORFEO EURIDICE NOVEMBER 14,17,20,22(M), 2OO9 Opera Guide - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS What to Expect at the Opera ..............................................................................................................3 Cast of Characters / Synopsis ..............................................................................................................4 Meet the Composer .............................................................................................................................6 Gluck’s Opera Reform ..........................................................................................................................7 Meet the Conductor .............................................................................................................................9 Meet the Director .................................................................................................................................9 Meet the Cast .......................................................................................................................................10 The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice ....................................................................................................12 OPERA: Then and Now ........................................................................................................................13 Operatic Voices .....................................................................................................................................17 Suggested Classroom Activities -

History of Music

HISTORY OF MUSIC THE ROMANTIC ERA Created by J. Rogers (2015) 2 GOWER COLLEGE SWANSEA MUSIC Table of Contents Romantic Era Introduction (1830 – 1910) ............................................. 4 Programme Music ........................................................................................ 5 Concert Overture .............................................................................................. 5 Programme Symphony ....................................................................................... 6 Symphonic Poem ................................................................................................. 9 Romantic Piano Music ............................................................................... 11 Lieder and Song-cycles .............................................................................. 12 Opera and Music Dramas ......................................................................... 15 Italian Opera ..................................................................................................... 15 Music Dramas ................................................................................................... 16 Leitmotifs in The Ring ..................................................................................... 17 GOWER COLLEGE SWANSEA 3 MUSIC History of Music The History of Music can be broadly divided into separate periods of time, each with its own characteristics or musical styles. Musical style does not, of course, change overnight. It can often be a gradual process -

Eine Symphonie Zu Dantes Divina Commedia Deux Légendes

Liszt SYMPHONIC POEMS VOL. 5 Eine Symphonie zu Dantes Divina Commedia Deux Légendes BBC Philharmonic GIANANDREA NOSEDA CHAN 10524 Franz Liszt (1811–1886) Symphonic Poems, Volume 5 AKG Images, London Images, AKG Eine Symphonie zu Dantes Divina Commedia, S 109* 42:06 for large orchestra and women’s chorus Richard Wagner gewidmet I Inferno 20:03 1 Lento – Un poco più accelerando – Allegro frenetico. Quasi doppio movimento (Alla breve) – Più mosso – Presto molto – Lento – 6:31 2 Quasi andante, ma sempre un poco mosso – 5:18 3 Andante amoroso. Tempo rubato – Più ritenuto – 3:42 4 Tempo I. Allegro (Alla breve) – Più mosso – Più mosso – Più moderato (Alla breve) – Adagio 4:32 II Purgatorio 21:57 5 Andante con moto quasi allegretto. Tranquillo assai – Più lento – Un poco meno mosso – 6:22 6 Lamentoso – 5:11 Franz Liszt, steel plate engraving, 1858, by August Weger (1823 –1892) after a photograph 3 Liszt: Symphonic Poems, Volume 5 7 [L’istesso tempo] – Poco a poco più di moto – 3:42 8 Magnificat. L’istesso tempo – Poco a poco accelerando e Deux Légendes published by Editio Musica in Budapest in crescendo sin al Più mosso – Più mosso ma non troppo – TheDeux Légendes, ‘St François d’Assise: la 1984. ‘St François d’Assise’ is scored for strings, Un poco più lento – L’istesso tempo, ma quieto assai 6:40 prédication aux oiseaux’ (St Francis of Assisi: woodwind and harp only, while ‘St François de the Sermon to the Birds) and ‘St François de Paule’ adds four horns, four trombones and a Deux Légendes, S 354 19:10 Paule marchant sur les flots’ (St Francis of bass trombone. -

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices Valid Until Friday 25 October 2019 Unless Stated Otherwise

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices valid until Friday 25 October 2019 unless stated otherwise ‘The lover with the rose in his hand’ from Le Roman de la 0115 982 7500 Rose (French School, c.1480), used as the cover for The Orlando Consort’s new recording of music by Machaut, entitled ‘The single rose’ (Hyperion CDA 68277). [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, As summer gives way to autumn (for those of us in the northern hemisphere at least), the record labels start rolling out their big guns in the run-up to the festive season. This year is no exception, with some notable high-profile issues: the complete Tchaikovsky Project from the Czech Philharmonic under Semyon Bychkov, and Richard Strauss tone poems from Chailly in Lucerne (both on Decca); the Beethoven Piano Concertos from Jan Lisiecki, and Mozart Piano Trios from Barenboim (both on DG). The independent labels, too, have some particularly strong releases this month, with Chandos discs including Bartók's Bluebeard’s Castle from Edward Gardner in Bergen, and the keenly awaited second volume of British tone poems under Rumon Gamba. Meanwhile Hyperion bring out another volume (no.79!) of their Romantic Piano Concerto series, more Machaut from the wonderful Orlando Consort (see our cover picture), and Brahms songs from soprano Harriet Burns. Another Hyperion Brahms release features as our 'Disc of the Month': the Violin Sonatas in a superb new recording from star team Alina Ibragimova and Cédric Tiberghien (see below). -

Raff's Arragement for Piano of Bach's Cello Suites

Six Sonatas for Cello by J.S.Bach arranged for the Pianoforte by JOACHIM RAFF WoO.30 Sonata No.1 in G major Sonate No.2 in D minor Sonate No.3 in C major Sonate No.4 in E flat major Sonate No.5 in C minor Sonate No.6 in D major Joachim Raff’s interest in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and the inspiration he drew from them is unmatched by any of the other major composers in the second half of the 19th century. One could speculate that Raff’s partiality for polyphonic writing originates from his studies of Bach’s works - the identification of “influenced by Bach” with “Polyphony” is a popular idea but is often questionable in terms of scientific correctness. Raff wrote numerous original compositions in polyphonic style and used musical forms of the baroque period. However, he also created a relatively large number of arrangements and transcriptions of works by Bach. Obviously, Bach’s music exerted a strong attraction on Raff that went further than plain admiration. Looking at Raff’s arrangements one can easily detect his particular interest in those works by Bach that could be supplemented by another composer. Upon these models Raff could fit his reverence for the musical past as well as exploit his never tiring interest in the technical aspects of the art of composition. One of the few statements we have by Raff about the basics of his art reveal his concept of how to attach supplements to works by Bach. Raff wrote about his orchestral arrangement of Bach’s Ciaconna in d minor for solo violin: "Everybody who has studied J.S. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation.