Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

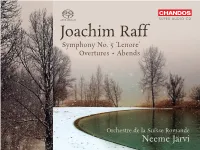

Joachim Raff Symphony No

SUPER AUDIO CD Joachim Raff Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ Overtures • Abends Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Neeme Järvi © Mary Evans Picture Library Picture © Mary Evans Joachim Raff Joachim Raff (1822 – 1882) 1 Overture to ‘Dame Kobold’, Op. 154 (1869) 6:48 Comic Opera in Three Acts Allegro – Andante – Tempo I – Poco più mosso 2 Abends, Op. 163b (1874) 5:21 Rhapsody Orchestration by the composer of the fifth movement from Piano Suite No. 6, Op. 163 (1871) Moderato – Un poco agitato – Tempo I 3 Overture to ‘König Alfred’, WoO 14 (1848 – 49) 13:43 Grand Heroic Opera in Four Acts Andante maestoso – Doppio movimento, Allegro – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto, quasi Tempo I – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto – Andante maestoso 4 Prelude to ‘Dornröschen’, WoO 19 (1855) 6:06 Fairy Tale Epic in Four Parts Mäßig bewegt 5 Overture to ‘Die Eifersüchtigen’, WoO 54 (1881 – 82) 8:25 Comic Opera in Three Acts Andante – Allegro 3 Symphony No. 5, Op. 177 ‘Lenore’ (1872) 39:53 in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur Erste Abtheilung. Liebesglück (First Section. Joy of Love) 6 Allegro 10:29 7 Andante quasi Larghetto 8:04 Zweite Abtheilung. Trennung (Second Section. Separation) 8 Marsch-Tempo – Agitato 9:13 Dritte Abtheilung. Wiedervereinigung im Tode (Third Section. Reunion in Death) 9 Introduction und Ballade (nach G. Bürger’s ‘Lenore’). Allegro – Un poco più mosso (quasi stretto) 11:53 TT 80:55 Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Bogdan Zvoristeanu concert master Neeme Järvi 4 Raff: Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ / Overtures / Abends Symphony No. 5 in E major, Op. -

574040-41 Itunes Beethoven

BEETHOVEN Chamber Music Piano Quartet in E flat major • Six German Dances Various Artists Ludwig van ¡ Piano Quartet in E flat major, Op. 16 (1797) 26:16 ™ I. Grave – Allegro ma non troppo 13:01 £ II. Andante cantabile 7:20 BEE(1T77H0–1O827V) En III. Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo 5:54 1 ¢ 6 Minuets, WoO 9, Hess 26 (c. 1799) 12:20 March in D major, WoO 24 ‘Marsch zur grossen Wachtparade ∞ No. 1 in E flat major 2:05 No. 2 in G major 1:58 2 (Grosser Marsch no. 4)’ (1816) 8:17 § No. 3 in C major 2:29 March in C major, WoO 20 ‘Zapfenstreich no. 2’ (c. 1809–22/23) 4:27 ¶ 3 • No. 4 in F major 2:01 4 Polonaise in D major, WoO 21 (1810) 2:06 ª No. 5 in D major 1:50 Écossaise in D major, WoO 22 (c. 1809–10) 0:58 No. 6 in G major 1:56 5 3 Equali, WoO 30 (1812) 5:03 º 6 Ländlerische Tänze, WoO 15 (version for 2 violins and double bass) (1801–02) 5:06 6 No. 1. Andante 2:14 ⁄ No. 1 in D major 0:43 No. 2 in D major 0:42 7 No. 2. Poco adagio 1:42 ¤ No. 3. Poco sostenuto 1:05 ‹ No. 3 in D major 0:38 8 › No. 4 in D minor 0:43 Adagio in A flat major, Hess 297 (1815) 0:52 9 fi No. 5 in D major 0:42 March in B flat major, WoO 29, Hess 107 ‘Grenadier March’ No. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Abramiuk, M.A. The Foundations of Cognitive Archaeology. Cambridge & London: The MIT Press, 2012. Abbott, Evelyn, and E.D. Mansfield. Primer of Greek Grammar. Newbury Port, MA: Focus Classical Reprints, 2000 [1893]. Ahl, Frederick. “The Art of Safe Criticism in Greece and Rome.” American Journal of Philology 105 (1984): 174–208. Ahl, Frederick. Metaformations: Soundplay and Wordplay in Ovid and Other Classical Poets. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1985. Ahl, Frederick. “Making Poets Serve the Established Order: Censoring Meaning in Sophocles, Virgil, and W.S. Gilbert.” Partial Answers 10/2 (2011): 271–301. Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow. New York: The New Press, 2010. Alexanderson, Bengt. “Darius in the Persians.” Eranos 65 (1967): 1–11. Alexiou, Margaret. The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge Uni- versity Press, 1974. Alfaro, Luis. “Electricidad: A Chicano Take on the Tragedy of Electra.” American Theatre 23/2 (February 2006): 63, 66–85. Alley, Henry M. “A Rediscovered Eulogy: Virginia. Woolf’s ‘Miss Janet Case: Classical Scholar and Teacher.’” Twentieth Century Literature 28/3 (1982): 290–301. Allison, John. Review of Carl Orff: Prometheus (Roland Hermann, Colette Lorand, Fritz Uhl; Bavarian Rundfunks Symphony Orchestra and Women’s Chorus, Rafael Kubelík, cond.; live recording, Munich, 1975), Orfeo C526992I (1999). http://www.classical-music.com/review/orff-2. Andreas, Sr., James R. “Signifyin’ on The Tempest in Mama Day.” In Shakespeare and Appropriation, (eds.) Christy Desmet and Robert Sawyer. London: Routledge, 1999. Aristophanes. Lysistrata, The Women’s Festival and Frogs, (ed.) and trans. Michael Ewans. Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 2011. Armstrong, Richard H. -

Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes Bernie Neville

Trickster's Way Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 4 1-1-2003 Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes Bernie Neville Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/trickstersway Recommended Citation Neville, Bernie (2003) "Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes ," Trickster's Way: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/trickstersway/vol2/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trickster's Way by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neville: Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes Trickster's Way Vol 2 Taking Care of Business in the Age of Hermes Bernie Neville The Story of Our Times For the past half century, we have been hearing from various sources that human consciousness and culture is undergoing some sort of transformation.[1] The story we hear is sometimes the story of a collapsing civilization and an inevitable global catastrophe and sometimes a story of a coming bright new age, but the pessimistic and optimistic versions have certain themes in common when they address the nature of th contemporary world. The story we hear is a story of complexity and chaos, of the dissolution of boundaries, of deceit, denial and delusion, of the preference for image over substance, of the loss o familial and tribal bonds, of the deregulation of markets, ideas and ethics, of an unwillingness of national leaders to confront reality and tell the truth, of the abandonment of rationality, of the proliferation of information, of a market-place so noisy that nothing can be clearly heard, of a world seen through a distorting lens, of an ever-tightening knot which we cannot unravel, or an ever-unraveling knot which we cannot tighten, of planetary dilemmas so profound that we cannot even think about them sensibly, let alone address them. -

Osmo Vänskä, Conductor Augustin Hadelich, Violin

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2019-2020 Mellon Grand Classics Season December 6 and 8, 2019 OSMO VÄNSKÄ, CONDUCTOR AUGUSTIN HADELICH, VIOLIN CARL NIELSEN Helios Overture, Opus 17 WOLFGANG AMADEUS Concerto No. 2 in D major for Violin and Orchestra, K. 211 MOZART I. Allegro moderato II. Andante III. Rondeau: Allegro Mr. Hadelich Intermission THOMAS ADÈS Violin Concerto, “Concentric Paths,” Opus 24 I. Rings II. Paths III. Rounds Mr. Hadelich JEAN SIBELIUS Symphony No. 3 in C major, Opus 52 I. Allegro moderato II. Andantino con moto, quasi allegretto III. Moderato — Allegro (ma non tanto) Dec. 6-8, 2019, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA CARL NIELSEN Helios Overture, Opus 17 (1903) Carl Nielsen was born in Odense, Denmark on June 9, 1865, and died in Copenhagen on October 3, 1931. He composed his Helios Overture in 1903, and it was premiered by the Danish Royal Orchestra conducted by Joan Svendsen on October 8, 1903. These performances mark the Pittsburgh Symphony premiere of the work. The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani and strings. Performance time: approximately 12 minutes. On September 1, 1889, three years after graduating from the Copenhagen Conservatory, Nielsen joined the second violin section of the Royal Chapel Orchestra, a post he held for the next sixteen years while continuing to foster his reputation as a leading figure in Danish music. His reputation as a composer grew with his works of the ensuing decade, most notably the Second Symphony and the opera Saul and David, but he was still financially unable to quit his job with the Chapel Orchestra to devote himself fully to composition. -

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M

WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M. Jones, S.-J. Bradley, T. Lowe, A. Thwaite) Notes to performers by Matthew Jones Walton, Menuhin and ‘shifting’ performance practice The use of vibrato and audible shifts in Walton’s works, particularly the Violin Sonata, became (somewhat unexpectedly) a fascinating area of enquiry and experimentation in the process of preparing for the recording. It is useful at this stage to give some historical context to vibrato. As late as in Joseph Joachim’s treatise of 1905, the renowned violinist was clear that vibrato should be used sparingly,1 through it seems that it was in the same decade that the beginnings of ‘continuous vibrato use’ were appearing. In the 1910s Eugene Ysaÿe and Fritz Kreisler are widely credited with establishing it. Robin Stowell has suggested that this ‘new’ vibrato began to evolve partly because of the introduction of chin rests to violin set-up in the early nineteenth century.2 I suspect the evolution of the shoulder rest also played a significant role, much later, since the freedom in the left shoulder joint that is more accessible (depending on the player’s neck shape) when using a combination of chin and shoulder rest facilitates a fluid vibrato. Others point to the adoption of metal strings over gut strings as an influence. Others still suggest that violinists were beginning to copy vocal vibrato, though David Milsom has observed that the both sets of musicians developed the ‘new vibrato’ roughly simultaneously.3 Mark Katz persuasively posits the idea that much of this evolution was due to the beginning of the recording process. -

History of Music

HISTORY OF MUSIC THE ROMANTIC ERA Created by J. Rogers (2015) 2 GOWER COLLEGE SWANSEA MUSIC Table of Contents Romantic Era Introduction (1830 – 1910) ............................................. 4 Programme Music ........................................................................................ 5 Concert Overture .............................................................................................. 5 Programme Symphony ....................................................................................... 6 Symphonic Poem ................................................................................................. 9 Romantic Piano Music ............................................................................... 11 Lieder and Song-cycles .............................................................................. 12 Opera and Music Dramas ......................................................................... 15 Italian Opera ..................................................................................................... 15 Music Dramas ................................................................................................... 16 Leitmotifs in The Ring ..................................................................................... 17 GOWER COLLEGE SWANSEA 3 MUSIC History of Music The History of Music can be broadly divided into separate periods of time, each with its own characteristics or musical styles. Musical style does not, of course, change overnight. It can often be a gradual process -

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Piano Quartet in E Op 47 (1842

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Piano Quartet in E♭ Op 47 (1842) Sostenuto assai — Allegro ma non troppo Scherzo. Molto vivace Andante cantabile Finale. Vivace Coming after his 'Liederjahre' of 1840 and the subsequent 'Symphonic Year' of 1841, 1842 was Schumann's 'Chamber Music Year': three string quartets, the particularly successful piano quintet and today's piano quartet. Such creativity may have been initiated by Schumann at last winning, in July 1840, the protracted legal case in which his ex-teacher Friedrich Wieck, attempted to forbid him from marrying Wieck's daughter, the piano virtuoso Clara. They were married on 12 September 1840, the day before Clara's 21st birthday. 1842, however, did not start well for the Schumanns. Robert accompanied Clara at the start of her concert tour of North Germany, but he tired of being in her shadow, returned home to Leipzig in a state of deep melancholy, and comforted himself with beer, champagne and, unable to compose, contrapuntal exercises. Clara's father spread an unfounded and malicious rumour that the Schumanns had separated. However, in April Clara returned and Robert started a two-month study of the string quartets of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. During June he wrote the first two of his own three quartets, the third following in July. He dedicated them to his Leipzig friend and colleague Felix Mendelssohn. The three quartets were first performed on September 13, for Clara's birthday. She thought them 'new and, at the same time, lucid, finely worked and always in quartet idiom' - a comment reflecting Schumann the critic's own view that the ‘proper’ quartet style should avoid ‘symphonic furore’ and aim rather for a conversational tone in which ‘everyone has something to say’. -

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices Valid Until Friday 25 October 2019 Unless Stated Otherwise

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices valid until Friday 25 October 2019 unless stated otherwise ‘The lover with the rose in his hand’ from Le Roman de la 0115 982 7500 Rose (French School, c.1480), used as the cover for The Orlando Consort’s new recording of music by Machaut, entitled ‘The single rose’ (Hyperion CDA 68277). [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, As summer gives way to autumn (for those of us in the northern hemisphere at least), the record labels start rolling out their big guns in the run-up to the festive season. This year is no exception, with some notable high-profile issues: the complete Tchaikovsky Project from the Czech Philharmonic under Semyon Bychkov, and Richard Strauss tone poems from Chailly in Lucerne (both on Decca); the Beethoven Piano Concertos from Jan Lisiecki, and Mozart Piano Trios from Barenboim (both on DG). The independent labels, too, have some particularly strong releases this month, with Chandos discs including Bartók's Bluebeard’s Castle from Edward Gardner in Bergen, and the keenly awaited second volume of British tone poems under Rumon Gamba. Meanwhile Hyperion bring out another volume (no.79!) of their Romantic Piano Concerto series, more Machaut from the wonderful Orlando Consort (see our cover picture), and Brahms songs from soprano Harriet Burns. Another Hyperion Brahms release features as our 'Disc of the Month': the Violin Sonatas in a superb new recording from star team Alina Ibragimova and Cédric Tiberghien (see below). -

Raff's Arragement for Piano of Bach's Cello Suites

Six Sonatas for Cello by J.S.Bach arranged for the Pianoforte by JOACHIM RAFF WoO.30 Sonata No.1 in G major Sonate No.2 in D minor Sonate No.3 in C major Sonate No.4 in E flat major Sonate No.5 in C minor Sonate No.6 in D major Joachim Raff’s interest in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and the inspiration he drew from them is unmatched by any of the other major composers in the second half of the 19th century. One could speculate that Raff’s partiality for polyphonic writing originates from his studies of Bach’s works - the identification of “influenced by Bach” with “Polyphony” is a popular idea but is often questionable in terms of scientific correctness. Raff wrote numerous original compositions in polyphonic style and used musical forms of the baroque period. However, he also created a relatively large number of arrangements and transcriptions of works by Bach. Obviously, Bach’s music exerted a strong attraction on Raff that went further than plain admiration. Looking at Raff’s arrangements one can easily detect his particular interest in those works by Bach that could be supplemented by another composer. Upon these models Raff could fit his reverence for the musical past as well as exploit his never tiring interest in the technical aspects of the art of composition. One of the few statements we have by Raff about the basics of his art reveal his concept of how to attach supplements to works by Bach. Raff wrote about his orchestral arrangement of Bach’s Ciaconna in d minor for solo violin: "Everybody who has studied J.S. -

VITA – 2020/21 Season “The Essence of Hadelich's

VITA – 2020/21 Season “The essence of Hadelich’s playing is beauty: reveling in the myriad ways of making a phrase come alive on the violin, delivering the musical message with no technical impediments whatsoever, and thereby revealing something from a plane beyond ours.” WASHINGTON POST Augustin Hadelich is one of the great violinists of our time. From Bach to Paganini, from Brahms to Bartók to Adès, he has mastered a wide-ranging and adventurous repertoire. He is often referred to by colleagues as a musician's musician. Named Musical America’s 2018 "Instrumentalist of the Year", he is consistently cited worldwide for his phenomenal technique, soulful approach, and insightful interpretations. Highlights of Augustin Hadelich’s 2020/21 season include appearances with the Atlanta, Baltimore, Colorado, Dallas, Milwaukee, North Carolina and Seattle symphony orchestras, as well as the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, WDR radio orchestra Cologne, Philharmonia Zürich, Dresden Philharmonic, ORF Vienna Radio Symphony, Danish National Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, BBC Scottish Orchestra, and Elbphilharmonie Orchestra Hamburg, where he was named Associate Artist starting with the 2019/20 season. Augustin Hadelich has appeared with every major orchestra in North America, including the Boston Symphony, Chicago Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia Orchestra, San Francisco Symphony. His worldwide presence has been rapidly rising, with recent appearances with the Bavarian Radio Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Philharmonic, Munich Philharmonic, Orquesta Nacional de España, Oslo Philharmonic, São Paulo Symphony, the radio orchestras of Frankfurt, Saarbrücken, Stuttgart, and Cologne, and the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields. -

A Structural Analysis of the Relationship Between Programme, Harmony and Form in the Symphonic Poems of Franz Liszt Keith Thomas Johns University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 A structural analysis of the relationship between programme, harmony and form in the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt Keith Thomas Johns University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Johns, Keith Thomas, A structural analysis of the relationship between programme, harmony and form in the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1927 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PROGRAMME, HARMONY AND FORM IN THE SYMPHONIC POEMS OF FRANZ LISZT. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from THE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by KEITH THOMAS JOHNS (M.Litt.,B.A.Hons.,Grad.Dip.Ed., F.L.C.M., F.T.C.L., L.T.C.L. ) SCHOOL OF CREATIVE ARTS 1986 i ABSTRACT This thesis examines the central concern in an analysis of the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt, that is, the relationship between programme,harmony and form. In order to make a thorough and clear analysis of this relationship a structural/semiotic analysis has been developed as the analysis of best fit. Historically it has been fashionable to see Liszt's symphonic poems in terms of sonata form or a form only making sense in terms of the attached programme. Both of these ideas are critically examined in this analysis.