WALTON, William Turner Piano Quartet / Violin Sonata / Toccata (M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

574040-41 Itunes Beethoven

BEETHOVEN Chamber Music Piano Quartet in E flat major • Six German Dances Various Artists Ludwig van ¡ Piano Quartet in E flat major, Op. 16 (1797) 26:16 ™ I. Grave – Allegro ma non troppo 13:01 £ II. Andante cantabile 7:20 BEE(1T77H0–1O827V) En III. Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo 5:54 1 ¢ 6 Minuets, WoO 9, Hess 26 (c. 1799) 12:20 March in D major, WoO 24 ‘Marsch zur grossen Wachtparade ∞ No. 1 in E flat major 2:05 No. 2 in G major 1:58 2 (Grosser Marsch no. 4)’ (1816) 8:17 § No. 3 in C major 2:29 March in C major, WoO 20 ‘Zapfenstreich no. 2’ (c. 1809–22/23) 4:27 ¶ 3 • No. 4 in F major 2:01 4 Polonaise in D major, WoO 21 (1810) 2:06 ª No. 5 in D major 1:50 Écossaise in D major, WoO 22 (c. 1809–10) 0:58 No. 6 in G major 1:56 5 3 Equali, WoO 30 (1812) 5:03 º 6 Ländlerische Tänze, WoO 15 (version for 2 violins and double bass) (1801–02) 5:06 6 No. 1. Andante 2:14 ⁄ No. 1 in D major 0:43 No. 2 in D major 0:42 7 No. 2. Poco adagio 1:42 ¤ No. 3. Poco sostenuto 1:05 ‹ No. 3 in D major 0:38 8 › No. 4 in D minor 0:43 Adagio in A flat major, Hess 297 (1815) 0:52 9 fi No. 5 in D major 0:42 March in B flat major, WoO 29, Hess 107 ‘Grenadier March’ No. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

César Franck's Violin Sonata in a Major

Honors Program Honors Program Theses University of Puget Sound Year 2016 C´esarFranck's Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer's Influence on the Violin Repertory Clara Fuhrman University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/honors program theses/21 César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer’s Influence on the Violin Repertory By Clara Fuhrman Maria Sampen, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements as a Coolidge Otis Chapman Scholar. University of Puget Sound, Honors Program Tacoma, Washington April 18, 2016 Fuhrman !2 Introduction and Presentation of My Argument My story of how I became inclined to write a thesis on Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major is both unique and essential to describe before I begin the bulk of my writing. After seeing the famously virtuosic violinist Augustin Hadelich and pianist Joyce Yang give an extremely emotional and perfected performance of Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major at the Aspen Music Festival and School this past summer, I became addicted to the piece and listened to it every day for the rest of my time in Aspen. I always chose to listen to the same recording of Franck’s Violin Sonata by violinist Joshua Bell and pianist Jeremy Denk, in my opinion the highlight of their album entitled French Impressions, released in 2012. After about a month of listening to the same recording, I eventually became accustomed to every detail of their playing, and because I had just started learning the Sonata myself, attempted to emulate what I could remember from the recording. -

This Paper Is a Revised Version of My Article 'Towards A

1 This paper is a revised version of my article ‘Towards a more consistent and more historical view of Bach’s Violoncello’, published in Chelys Vol. 32 (2004), p. 49. N.B. at the end of this document readers can download the music examples. Towar ds a different, possibly more historical view of Bach’s Violoncello Was Bach's Violoncello a small CGda Violoncello “played like a violin” (as Bach’s Weimar collegue Johann Gottfried Walther 1708 stated)? Lambert Smit N.B. In this paper 18 th century terms are in italics. Introduction Bias and acquired preferences sometimes cloud people’s views. Modern musicians’ fondness of their own instruments sometimes obstructs a clear view of the history of each single instrument. Some instrumentalists want to defend the territory of their own instrument or to enlarge 1 it. However, in the 18 th century specialization in one instrument, as is the custom today, was unknown. 2 Names of instruments in modern ‘Urtext’ editions can be misleading: in the Neue Bach Ausgabe the due Fiauti d’ Echo in Bach’s score of Concerto 4 .to (BWV 1049) are interpreted as ‘Flauto dolce’ (=recorder, Blockflöte, flûte à bec), whereas a Fiauto d’ Echo was actually a kind of double recorder, consisting of two recorders, one loud and one soft. (see internet and Bachs Orchestermusik by S. Rampe & D. Sackmann, p. 279280). 1 The bassoon specialist Konrad Brandt, however, argues against the habit of introducing a bassoon in every movement in Bach’s church music where oboes are played (the theory ‘wo Oboen, da auch Fagott’) BachJahrbuch '68. -

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Piano Quartet in E Op 47 (1842

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Piano Quartet in E♭ Op 47 (1842) Sostenuto assai — Allegro ma non troppo Scherzo. Molto vivace Andante cantabile Finale. Vivace Coming after his 'Liederjahre' of 1840 and the subsequent 'Symphonic Year' of 1841, 1842 was Schumann's 'Chamber Music Year': three string quartets, the particularly successful piano quintet and today's piano quartet. Such creativity may have been initiated by Schumann at last winning, in July 1840, the protracted legal case in which his ex-teacher Friedrich Wieck, attempted to forbid him from marrying Wieck's daughter, the piano virtuoso Clara. They were married on 12 September 1840, the day before Clara's 21st birthday. 1842, however, did not start well for the Schumanns. Robert accompanied Clara at the start of her concert tour of North Germany, but he tired of being in her shadow, returned home to Leipzig in a state of deep melancholy, and comforted himself with beer, champagne and, unable to compose, contrapuntal exercises. Clara's father spread an unfounded and malicious rumour that the Schumanns had separated. However, in April Clara returned and Robert started a two-month study of the string quartets of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. During June he wrote the first two of his own three quartets, the third following in July. He dedicated them to his Leipzig friend and colleague Felix Mendelssohn. The three quartets were first performed on September 13, for Clara's birthday. She thought them 'new and, at the same time, lucid, finely worked and always in quartet idiom' - a comment reflecting Schumann the critic's own view that the ‘proper’ quartet style should avoid ‘symphonic furore’ and aim rather for a conversational tone in which ‘everyone has something to say’. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Concertos and Six Chamber Pieces, Cover Ali the Major Pends of Szymanowski's Career and Thus Show the Composer's Stylistic Evolution

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. Udverslty of Alberta The Violln Muslc of Karol Szymanowski bv Frank Kwantat Ho O A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Music Edmonton, Alberta Fall, 2000 Acquïsiions and Acquisitions et Biùliographic Services sentrças bibriiraphiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exchism licence dowhg the exclusive pennettant à la National Li%,rary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reprodnce, loan, distriibute or seIl reproduire, prêter, ckibuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fmede microfichd~de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author re- ownershq, of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qpi protège cette thèse. thesis nor substaxitid extracts from it Ni la thése ni des extraits substantieis may be printed or othefwise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. One of the most important segments of Karol Szymanowski's (1882- 1937) comparatively srnall output is the music for solo violin with piano or orchestral accumpaniment. These works. consisting of two concertos and six chamber pieces, cover ali the major pends of Szymanowski's career and thus show the composer's stylistic evolution. The works Szymanowski's early period (1896-1909) reveai his Romantic mots. while the more innovative works of the middle period (1909-1918) demonstrate his growing interest in Impressionism. -

CONCERT of the MONTH by Dr Chang Tou Liang

Sensory Classics CONCERT OF THE MONTH By Dr Chang Tou Liang Stravinsky Symphony of Psalms Walton Belshazzar’s Feast Singapore Symphony Orchestra and Choruses Conducted by Lim Yau 15 April 2011, 7.30 pm Esplanade Concert Hall Tickets available from SISTIC The Singapore Symphony Chorus celebrates its 31st year in 2011. For an ensemble more accustomed to performing the great symphonic choral works of the 18th and 19th centuries, the challenge is taking on contemporary works. “How can you call yourself a 21st century chorus if you don’t master 20th century music?” questioned its long-time Music Director Lim Yau. To this cause, he has championed 20th century choral works over the decades, leading memorable performances of music by Hindemith, Schoenberg, Poulenc, Janacek and MacMillan. This year’s offerings are however the most ambitious. The season of 1930-31 was an important one for choral music, as it was witness to the first performances of two most enduring choral works from the 20th century. Both were memorable in different ways, and here’s how: IGOR STRAVINSKY SIR WILLIAM WALTON (1882-1971) (1902-83) Symphony of Psalms Belshazzar’s Feast Composed for: Composed for: 50th anniversary of the Leeds Festival Boston Symphony Orchestra First conducted by: First conducted by: Serge Koussevitzky Sir Malcolm Sargent Setting of: Psalms No.39, 40 and 150 (in Latin) Setting of: Selections from the books of Daniel and Revelation (in English) Notable for: Stravinsky’s reaffirmation of his faith and roots in the Russian Notable for: Technicolour re-enactment -

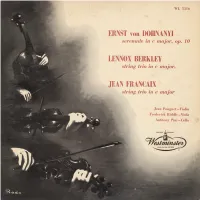

Serenade in E Major, Op. 10 / String Trio in C Major

NATURAL BALANCE LONG PLAYING RECORDS WL 5316 JEAN POUGNET Jean Pougnet was born in 1907. ERNST VON DOHNANYI He started to study the violin at age of 5, was taught by his sister for two years, then jor by Prof. Rowsby Woof, at age 11 entered Royal Academy of Music, winning three scholar- Serenade in © Major, Op. 10 ships in succession, until 1925. His first London recital age 15, first Promenade Concert, the next year subsequent experience with chamber music, solo playing, both for Music Societies, Public concerts and radio. At outbreak of war, undertook some special work for BBC until 1942, then joined LENNOX BERKELEY London Philharmonic Orchestra as concertmaster, in 1945 left the orchestra and has since concentrated on solo work. String Trio : FREDERICK CRAIG RIDDLE “Born in 1912 im Liverpool. Kent Scholar at Royal College of Music 1928-1933. Winner of Tagore Gold Medal 1933. Professor of viola at Royal College of Music. JEAN FRANCAIX Principal viola of the London Symphony Orchestra 1935-1938 and of London Philhar- monic Orchestra 1939-1952. String Trio in C Major ANTHONY PINI String C Trio, Ma Born in Buenos Aires. Came to England in 1912. ANTHONY PINI Has devoted much time to Chamber Music, co-founder of Philharmonia Quartet with Jean JEAN POUGNET FREDERICK RIDDLE Pougnet, Frederick Riddle and Henry Holst. Has played in most capitals of Europe as Violin Viola Cello soloist and toured America four times also with Sir Thomas Beecham and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. He is Professor of cello Guildhall School of Music and Birming- The three string trios that comprise this recorded recital are each of them worthwhile ham College. -

BMS News August 2018

BRITISH MUSIC SOCIETY nAUGUST 2018 ews THE PIPER OF DREAMS A Ruth Gipps perspective ELGAR ENIGMA Rachel Barton Pine’s magnifica musica Agenda British Music Society’s news and events What you missed at the AGM his report of our Annual General Meeting covers the key areas of the Recordings Chairman’s TBritish Music Society’s activities as The generous bequest from Michael follows: Hurd for recordings has finally come to an end unfortunately and it is only to be welcome E-News expected that new releases by the Society will In the summer of 2017, Harold Diamond be less frequent now in number. New 'll keep my address short as the indicated his need to retire from his position opportunities to record will largely depend Chairman's Report from this as the monthly E-news editor. There were on receipt of grants from other funding year's AGM on June 30 is being difficulties finding another member with the bodies. I necessary time and the increasingly In November 2017, the songs of Arthur reproduced in this edition of Printed demanding technological skills to do this job. Benjamin and Edgar Bainton with Susan News. What it will not tell you is In light of this, the decision was made to Bickley (mezzo), Christopher Gillett (tenor) Dominic Daula, our new Journal employ Michael Wilkinson and Nicholas and Wendy Hiscocks (piano) with some Editor, joined the Committee at the Keyworth of Revolution Arts to conduct the funding from The Edgar Bainton Society AGM and John Gibbons revealed work for an agreed sum of £100 per month. -

Download Booklet

D I F F E R E N T W O R L D Diana Galvydyte Produced and Engineered by Raphaël Mouterde Edited and Mastered by Raphaël Mouterde Recorded on December 19th - 20th Dec 2011 and January 5th - 6th 2012 at The Music Room, Champs Hill, West Sussex, UK Christopher Guild Photographs of Diana and Chris by Benjamin Harte Executive Producer for Champs Hill Records: Alexander Van Ingen VYTAUTAS BARKAUSKAS (b.1931) A DIFFERENT WORLD PARTITA FOR SOLO VIOLIN OP.12 (1967) 1 i Praeludium 0’57 2 ii Scherzo 1’35 The cult of the instrumental virtuoso dates from the early 19th century, when the 3 iii Grave 2’28 burgeoning Romantic movement started to see preternaturally gifted 4 iv Toccata 1’29 instrumentalists as a species of magician, able to conjure music out of the air as if 5 v Postludium 1’40 by magic, and move audiences to extremes of emotion and excitement by the deep EDUARDAS BALSYS (1919-1984) expressivenesss and amazing technical bravura of their playing. The archetypal 6 RAUDA (LAMENT) FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO 3’46 figure who bestowed this image on players of the violin was of course Niccolò 7 DREBULYTÈ IŠDYKÉLÈ (MISCHIEVOUS DREBULYTÈ) FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO 1’55 Paganini, but the tradition of the virtuoso violin showpiece has persisted From the ballet ‘Eglè, Queen of the Serpents (1960) throughout the 20th century and into the 21st. The present recital is devoted JOE SCHITTINO (b.1977) largely to bravura violin works from the mid-20th century onwards, and mostly to 8 POEM ‘EGLÈ’ FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO (2011) Premiere recording 10’26 those produced by composers from the Baltic region, alternating and contrasting ESA-PEKKA SALONEN (b.1958) works for unaccompanied violin with those for violin and piano.