(Re)Constructing Johann Sebastian Bach: Reception History and Performance Practice in New York City During

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Atomic

What to Expect from doctor atomic Opera has alwayS dealt with larger-than-life Emotions and scenarios. But in recent decades, composers have used the power of THE WORK DOCTOR ATOMIC opera to investigate society and ethical responsibility on a grander scale. Music by John Adams With one of the first American operas of the 21st century, composer John Adams took up just such an investigation. His Doctor Atomic explores a Libretto by Peter Sellars, adapted from original sources momentous episode in modern history: the invention and detonation of First performed on October 1, 2005, the first atomic bomb. The opera centers on Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, in San Francisco the brilliant physicist who oversaw the Manhattan Project, the govern- ment project to develop atomic weaponry. Scientists and soldiers were New PRODUCTION secretly stationed in Los Alamos, New Mexico, for the duration of World Alan Gilbert, Conductor War II; Doctor Atomic focuses on the days and hours leading up to the first Penny Woolcock, Production test of the bomb on July 16, 1945. In his memoir Hallelujah Junction, the American composer writes, “The Julian Crouch, Set Designer manipulation of the atom, the unleashing of that formerly inaccessible Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer source of densely concentrated energy, was the great mythological tale Brian MacDevitt, Lighting Designer of our time.” As with all mythological tales, this one has a complex and Andrew Dawson, Choreographer fascinating hero at its center. Not just a scientist, Oppenheimer was a Leo Warner and Mark Grimmer for Fifty supremely cultured man of literature, music, and art. He was conflicted Nine Productions, Video Designers about his creation and exquisitely aware of the potential for devastation Mark Grey, Sound Designer he had a hand in designing. -

Joachim Raff Symphony No

SUPER AUDIO CD Joachim Raff Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ Overtures • Abends Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Neeme Järvi © Mary Evans Picture Library Picture © Mary Evans Joachim Raff Joachim Raff (1822 – 1882) 1 Overture to ‘Dame Kobold’, Op. 154 (1869) 6:48 Comic Opera in Three Acts Allegro – Andante – Tempo I – Poco più mosso 2 Abends, Op. 163b (1874) 5:21 Rhapsody Orchestration by the composer of the fifth movement from Piano Suite No. 6, Op. 163 (1871) Moderato – Un poco agitato – Tempo I 3 Overture to ‘König Alfred’, WoO 14 (1848 – 49) 13:43 Grand Heroic Opera in Four Acts Andante maestoso – Doppio movimento, Allegro – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto, quasi Tempo I – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto – Andante maestoso 4 Prelude to ‘Dornröschen’, WoO 19 (1855) 6:06 Fairy Tale Epic in Four Parts Mäßig bewegt 5 Overture to ‘Die Eifersüchtigen’, WoO 54 (1881 – 82) 8:25 Comic Opera in Three Acts Andante – Allegro 3 Symphony No. 5, Op. 177 ‘Lenore’ (1872) 39:53 in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur Erste Abtheilung. Liebesglück (First Section. Joy of Love) 6 Allegro 10:29 7 Andante quasi Larghetto 8:04 Zweite Abtheilung. Trennung (Second Section. Separation) 8 Marsch-Tempo – Agitato 9:13 Dritte Abtheilung. Wiedervereinigung im Tode (Third Section. Reunion in Death) 9 Introduction und Ballade (nach G. Bürger’s ‘Lenore’). Allegro – Un poco più mosso (quasi stretto) 11:53 TT 80:55 Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Bogdan Zvoristeanu concert master Neeme Järvi 4 Raff: Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ / Overtures / Abends Symphony No. 5 in E major, Op. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

The Bach Choir Commissions Ten Composers This Season, Including Richard Blackford & Gabriel Jackson at the Royal Festival Hall

The Bach Choir commissions ten composers this season, including Richard Blackford & Gabriel Jackson at the Royal Festival Hall Sunday 24 October 2021, 15:00 Royal Festival Hall Gabriel Jackson The Promise WORLD PREMIERE Tallis Hymn Vaughan Williams Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis Richard Blackford Vision of a Garden WORLD PREMIERE Fauré Cantique de Jean Racine Fauré Requiem The Bach Choir | David Hill conductor | Philharmonia Orchestra Katy Hill soprano | Gareth Brynmor John baritone ★★★★★ “I have to keep reminding myself that these people are amateurs: I can’t imagine a professional choir giving a more perfect and passionate performance.” The Independent on the Choir’s performance of Bach’s B Minor Mass, February 2020 As they return to live music-making after a year and a half of silence, The Bach Choir and Music Director David Hill announce the premieres of ten newly-commissioned contemporary choral works. Three of the works to be performed this season use texts written by members of the Choir, including the Royal Festival Hall premiere of Richard Blackford’s covid-inspired cantata setting the medical diaries of a Choir member who spent three months in intensive care, and a climate-change inspired commission from Gabriel Jackson. This July, the Choir announces a call for scores for the Sir David Willcocks Carol Competition to premiere two new carols at Cadogan Hall, and heads to the studio to record six newly-commissioned chorales from award-winning young composers in its Bach Inspired project. The Bach Choir, David Hill and the Philharmonia Orchestra are joined at the Royal Festival Hall on 24 October 2021 by soprano Katy Hill and baritone Gareth Brynmor John for a post- COVID programme of music for reflection and hope including the world premiere of Richard Blackford’s Vision of a Garden, based on the COVID diaries of The Bach Choir member Peter Johnstone, who spent three months in intensive care with the virus in Spring 2020. -

A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet Thomas A

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-2-2014 A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet Thomas A. Labadorf University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Labadorf, Thomas A., "A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 332. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/332 A New Transcription and Performance Interpretation of J.S. Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy BWV 903 for Unaccompanied Clarinet Thomas A. Labadorf, D. M. A. University of Connecticut, 2014 A new transcription of Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy is presented to offset limitations of previous transcriptions by other editors. Certain shortcomings of the clarinet are addressed which add to the difficulty of creating an effective transcription for performance: the inability to sustain more than one note at a time, phrase length limited by breath capacity, and a limited pitch range. The clarinet, however, offers qualities not available to the keyboard that can serve to mitigate these shortcomings: voice-like legato to perform sweeping scalar and arpeggiated gestures, the increased ability to sustain melodic lines, use of dynamics to emphasize phrase shapes and highlight background melodies, and the ability to perform large leaps easily. A unique realization of the arpeggiated section takes advantage of the clarinet’s distinctive registers and references early treatises for an authentic wind instrument approach. A linear analysis, prepared by the author, serves as a basis for making decisions on phrase and dynamic placement. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-Flat Major (BWV 243A)*

The Sources of the Christmas Interpolations in J. S. Bach's Magnificat in E-flat Major (BWV 243a)* By Robert M. Cammarota Apart from changes in tonality and instrumentation, the two versions of J. S. Bach's Magnificat differ from each other mainly in the presence offour Christmas interpolations in the earlier E-flat major setting (BWV 243a).' These include newly composed settings of the first strophe of Luther's lied "Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her" (1539); the last four verses of "Freut euch und jubiliert," a celebrated lied whose origin is unknown; "Gloria in excelsis Deo" (Luke 2:14); and the last four verses and Alleluia of "Virga Jesse floruit," attributed to Paul Eber (1570).2 The custom of troping the Magnificat at vespers on major feasts, particu larly Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost, was cultivated in German-speaking lands of central and eastern Europe from the 14th through the 17th centu ries; it continued to be observed in Leipzig during the first quarter of the 18th century. The procedure involved the interpolation of hymns and popu lar songs (lieder) appropriate to the feast into a polyphonic or, later, a con certed setting of the Magnificat. The texts of these interpolations were in Latin, German, or macaronic Latin-German. Although the origin oftroping the Magnificat is unknown, the practice has been traced back to the mid-14th century. The earliest examples of Magnifi cat tropes occur in the Seckauer Cantional of 1345.' These include "Magnifi cat Pater ingenitus a quo sunt omnia" and "Magnificat Stella nova radiat. "4 Both are designated for the Feast of the Nativity.' The tropes to the Magnificat were known by different names during the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. -

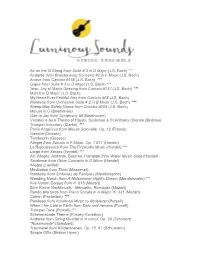

Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Andante from Brandenburg Concerto #2 in F Major (J.S

Air on the G String from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Andante from Brandenburg Concerto #2 in F Major (J.S. Bach) Arioso from Cantata #156 (J.S. Bach) *** Gigue from Suite # 3 in D Major (J.S. Bach) *** Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring from Cantata #147 (J.S. Bach) *** March in D Major (J.S. Bach) My Heart Ever Faithful Aria from Cantata #68 (J.S. Bach) Rondeau from Orchestral Suite # 2 in B Minor (J.S. Bach) *** Sheep May Safely Graze from Cantata #208 (J.S. Bach) Minuet in G (Beethoven) Ode to Joy from Symphony #9 (Beethoven) Variations on a Theme of Haydn, Sicilienne & St Anthony Chorale (Brahms) Trumpet Voluntary (Clarke) *** Panis Angelicus from Messe Solonelle, Op. 12 (Franck) Gavotte (Gossec) Tambourin (Gossec) Allegro from Sonata in F Major, Op. 1 #11 (Handel) La Rejouissance from The Fireworks Music (Handel) *** Largo from Xerxes (Handel) *** Air, Allegro, Andante, Bourree, Hornpipe from Water Music Suite (Handel) Sarabane from Oboe Concerto in G Minor (Handel) Allegro (Loeillet) Meditation from Thais (Massenet) Rondeau from Sinfonies de Fanfares (Mendelssohn) Wedding March from A Midsummer Night's Dream (Mendelssohn) *** Ave Verum Corpus from K. 618 (Mozart) Eine Kleine Nachtmusik - Menuetto, Romanza (Mozart) Rondo alla turca from Piano Sonata in A Major, K. 331 (Mozart) Canon (Pachelbel) *** Rondeau from Incidental Music to Abdelazer (Purcell) When I Am Laid in Earth from Dido and Aeneas (Purcell) Trumpet Tune (Purcell) *** Scheherazade Theme (Rimsky-Korsakov) Andante from String Quartet in A minor, Op. 29 (Schubert) "Rosamunde" (Schubert) Traumerei from Kinderscenen, Op. 15, #7 (Schumann) Simple Gifts (Shaker Hymn) Presto from Sonatina in F Major (Telemann) Vivace from Sonata in F Major for flute (Telemann) Be Thou My Vision (Traditional Irish Melody) Danza Pastorale from Violin Concerto in E Major, Op. -

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis

Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis All BWV (All data), numerical order Print: 25 January, 1997 To be BWV Title Subtitle & Notes Strength placed after 1 Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern Kantate am Fest Mariae Verkündigung (Festo annuntiationis Soli: S, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno I, II; Ob. da Mariae) caccia I, II; Viol. conc. I, II; Viol. rip. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 2 Ach Gott, von Himmel sieh darein Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 2 post Soli: A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromb. I - IV; Ob. I, II; Trinitatis) Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 3 Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid Kantate am zweiten Sonntag nach Epiphanias (Dominica 2 Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Corno; Tromb.; Ob. post Epiphanias) d'amore I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Cont. 4 Christ lag in Todes Banden Kantate am Osterfest (Feria Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Cornetto; Tromb. I, II, III; Viol. I, II; Vla. I, II; Cont. 5 Wo soll ich fliehen hin Kantate am 19. Sonntag nach Trinitatis (Dominica 19 post Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Tromba da tirarsi; Trinitatis) Ob. I, II; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. (Vcl. picc.?); Cont. 6 Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden Kantate am zweiten Osterfesttag (Feria 2 Paschatos) Soli: S, A, T, B. Chor: S, A, T, B. Instr.: Ob. I, II; Ob. da caccia; Viol. I, II; Vla.; Vcl. picc. (Viola pomposa); Cont. 7 Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam Kantate am Fest Johannis des Taüfers (Festo S. -

A Non-Definitive List of Most of the Concerts and Work (And the Odd Function) Presented, Promoted and Performed by the Bach Society of Queensland and the Bach Choir

A non-definitive list of most of the concerts and work (and the odd function) presented, promoted and performed by The Bach Society of Queensland and the Bach Choir. Regular occasions such as The Annual Bach Prizes, some Messiah Performances, Carol Singing and Soirees have not all been listed individually each and every year. Blue denotes items of significance. 1971 8 Jul First Fundraising Concert: JS Bach Sonata No 2 for Violin and Harpsichord; Granados Six Tornadillas; German lieder songs; Prokofiev 4th Piano Sonata 1 Aug The Inaugural Bach Society Concert JS Bach Fifth Brandenburg Concerto, the B-Minor Flute Suite, The Coffee Cantata 1972 18 Jun The Bach Choir under John Thompson: Vivaldi Four Violin Concertos, Klavier Concerto in B Minor; JS Bach Sinfonia Concertante in A Minor Plus three items by (their premier performance) Aug/Sept Sponsored Recitals by internationally acclaimed harpsichordist Dorothy White 27 Nov “Monday-Evening-with-Bach” free 1973 18 Feb JS Bach Concerto in F Major; Telemann Concerto in C Minor 15 Apr QYO Brass Ensemble: two Gabrieli Canzone; JS Bach Sonata No 3 for unaccompanied ‘Cello, Brandenburg Concerto No 3 21 July An instructive evening on Bach’s Preludes and Fugues 10/11 Aug JS Bach St Matthew Passion: rarely heard in Brisbane before 11 Nov JS Bach Cantata #10 Meine Seel erhebt den Herren, Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D 1974 21 Apr At home - soiree. The first of many. JS Bach Ah My Savior from Christmas Oratorio, Have Mercy Lord from St Matthew Passion 1975 26 May Together with Concert Society Orchestra - JS Bach Magnificat : (the biggest challenge the choir had yet faced); Johann Christian Bach Sinfonia in E for Two Orchestras, Op 18 No 5; JS Bach The Third Brandenburg Concerto in G for Strings 16 Jun Bach-B-Que at Rosevale, near Ipswich the first of many. -

The American Bach Society the Westfield Center

The Eastman School of Music is grateful to our festival sponsors: The American Bach Society • The Westfield Center Christ Church • Memorial Art Gallery • Sacred Heart Cathedral • Third Presbyterian Church • Rochester Chapter of the American Guild of Organists • Encore Music Creations The American Bach Society The American Bach Society was founded in 1972 to support the study, performance, and appreciation of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach in the United States and Canada. The ABS produces Bach Notes and Bach Perspectives, sponsors a biennial meeting and conference, and offers grants and prizes for research on Bach. For more information about the Society, please visit www.americanbachsociety.org. The Westfield Center The Westfield Center was founded in 1979 by Lynn Edwards and Edward Pepe to fill a need for information about keyboard performance practice and instrument building in historical styles. In pursuing its mission to promote the study and appreciation of the organ and other keyboard instruments, the Westfield Center has become a vital public advocate for keyboard instruments and music. By bringing together professionals and an increasingly diverse music audience, the Center has inspired collaborations among organizations nationally and internationally. In 1999 Roger Sherman became Executive Director and developed several new projects for the Westfield Center, including a radio program, The Organ Loft, which is heard by 30,000 listeners in the Pacific 2 Northwest; and a Westfield Concert Scholar program that promotes young keyboard artists with awareness of historical keyboard performance practice through mentorship and concert opportunities. In addition to these programs, the Westfield Center sponsors an annual conference about significant topics in keyboard performance. -

Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany. Died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany. Orchestral Suite No. 3 in D Major, BWV 1068 Although the dating of Bach’s four orchestral suites is uncertain, the third was probably written in 1731. The score calls for two oboes, three trumpets, timpani, and harpsichord, with strings and basso continuo. Performance time is approximately twenty -one minutes. The Chicago Sympho ny Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite were given at the Auditorium Theatre on October 23 and 24, 1891, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on May 15 , 16, 17, and 20, 2003, with Jaime Laredo conducting. The Orchestra first performed the Air and Gavotte from this suite at the Ravinia Festival on June 29, 1941, with Frederick Stock conducting; the complete suite was first performed at Ravinia on August 5 , 1948, with Pierre Monteux conducting, and most recently on August 28, 2000, with Vladimir Feltsman conducting. When the young Mendelssohn played the first movement of Bach’s Third Orchestral Suite on the piano for Goethe, the poet said he could see “a p rocession of elegantly dressed people proceeding down a great staircase.” Bach’s music was nearly forgotten in 1830, and Goethe, never having heard this suite before, can be forgiven for wanting to attach a visual image to such stately and sweeping music. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when Bach’s name meant little to music lovers and when these four orchestral suites weren’t considered landmarks.