74Th Baldwin-Wallace College Bach Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

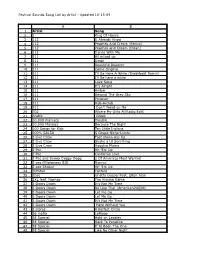

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

The Bach Choir Commissions Ten Composers This Season, Including Richard Blackford & Gabriel Jackson at the Royal Festival Hall

The Bach Choir commissions ten composers this season, including Richard Blackford & Gabriel Jackson at the Royal Festival Hall Sunday 24 October 2021, 15:00 Royal Festival Hall Gabriel Jackson The Promise WORLD PREMIERE Tallis Hymn Vaughan Williams Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis Richard Blackford Vision of a Garden WORLD PREMIERE Fauré Cantique de Jean Racine Fauré Requiem The Bach Choir | David Hill conductor | Philharmonia Orchestra Katy Hill soprano | Gareth Brynmor John baritone ★★★★★ “I have to keep reminding myself that these people are amateurs: I can’t imagine a professional choir giving a more perfect and passionate performance.” The Independent on the Choir’s performance of Bach’s B Minor Mass, February 2020 As they return to live music-making after a year and a half of silence, The Bach Choir and Music Director David Hill announce the premieres of ten newly-commissioned contemporary choral works. Three of the works to be performed this season use texts written by members of the Choir, including the Royal Festival Hall premiere of Richard Blackford’s covid-inspired cantata setting the medical diaries of a Choir member who spent three months in intensive care, and a climate-change inspired commission from Gabriel Jackson. This July, the Choir announces a call for scores for the Sir David Willcocks Carol Competition to premiere two new carols at Cadogan Hall, and heads to the studio to record six newly-commissioned chorales from award-winning young composers in its Bach Inspired project. The Bach Choir, David Hill and the Philharmonia Orchestra are joined at the Royal Festival Hall on 24 October 2021 by soprano Katy Hill and baritone Gareth Brynmor John for a post- COVID programme of music for reflection and hope including the world premiere of Richard Blackford’s Vision of a Garden, based on the COVID diaries of The Bach Choir member Peter Johnstone, who spent three months in intensive care with the virus in Spring 2020. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Bach Festival the First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation

Bach Festival The First Collegiate Bach Festival in the Nation ANNOTATED PROGRAM APRIL 1921, 2013 THE 2013 BACH FESTIVAL IS MADE POSSIBLE BY: e Adrianne and Robert Andrews Bach Festival Fund in honor of Amelia & Elias Fadil DEDICATION ELINORE LOUISE BARBER 1919-2013 e Eighty-rst Annual Bach Festival is respectfully dedicated to Elinore Barber, Director of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute from 1969-1998 and Editor of the journal BACH—both of which she helped to found. She served from 1969-1984 as Professor of Music History and Literature at what was then called Baldwin-Wallace College and as head of that department from 1980-1984. Before coming to Baldwin Wallace she was from 1944-1969 a Professor of Music at Hastings College, Coordinator of the Hastings College-wide Honors Program, and Curator of the Rinderspacher Rare Score and Instrument Collection located at that institution. Dr. Barber held a Ph.D. degree in Musicology from the University of Michigan. She also completed a Master’s degree at the Eastman School of Music and received a Bachelor’s degree with High Honors in Music and English Literature from Kansas Wesleyan University in 1941. In the fall of 1951 and again during the summer of 1954, she studied Bach’s works as a guest in the home of Dr. Albert Schweitzer. Since 1978, her Schweitzer research brought Dr. Barber to the Schweitzer House archives (Gunsbach, France) many times. In 1953 the collection of Dr. Albert Riemenschneider was donated to the University by his wife, Selma. Sixteen years later, Dr. Warren Scharf, then director of the Conservatory, and Dr. -

1947 Bach Festival Program

Lhe J3ach Socieb; of J(afamazoo THE BACH SOCIETY is dedicated to the high purpose of promoting an annual Bach Festival, so Presents its First A nnual that local music-lovers may have the opportunity of hearing and performing the BACH FESTIVAL immortal masterpieces of ] ohann Sebastian Bach. SIX DAYS-FEBRUARY 27TH THROUGH MARCH 5TH, 1947 THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Dr. Paul Thompson, Honorary Chairman A COMMUNITY PROJECT Mrs. James B. Fleugel, General Chairman SPONSORED BY KALAMAZOO COLLEGE Mr. Harold B. Allen Mr. Irving Gilmore Mrs. William Race Mr. Willis B. Burdick Mr. Everett R. Hames Mr. Louis P. Simon PRESENTED IN STETSON CHAPEL Miss Francis Clark Mrs. Stuart Irvine Dr. Harold T. Smith, Treas. Mrs. A. B. Conn able, Jr. Mrs. M. Lee Johnson Mrs. Harry M. Snow HENRY OVERLEY, Director Mrs. Cameron Davis, Secy. Mrs. W. 0. Jones Mrs. Fred G. Stanley Mr. Harold DeWeerd Mrs. James Kirkpatrick Mr. L. W. Sutherland Dr. Willis F. Dunbar Mr. Henry Overley Mrs. A. J. Todd Dr. M. H. Dunsmore Mr. Frank K. Owen Mrs. Stanley K. Wood Mr. Ralph A. Patton CALENDAR OF EVENTS ORGAN RECITAL PATRON MEMBERS ARTHUR B. JENNINGS (We ~·egret that this list is incomplete. It contains all names received up to the date of the p1·inter's dead-line). assisted by th e Allen, G. H. Fowkes, Dr. and Mrs. A. Gordon Overley, Mr. and Mrs. Henry CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL A CAPPELLA CHOIR Appeldoorn, Mrs. John Friedman, Martin Pitkin, Mrs. J. A. Barr, E. Lawrence Gilmore, Irving Pratt, Mrs. Arthur ESTHER NELSON , Director Barrett, Wilson Grinnell Bros. -

75Thary 1935 - 2010

ANNIVERS75thARY 1935 - 2010 The Music & the Artists of the Bach Festival Society The Mission of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. is to enrich the Central Florida community through presentation of exceptionally high-quality performances of the finest classical music in the repertoire, with special emphasis on oratorio and large choral works, world-class visiting artists, and the sacred and secular music of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries in the High Baroque and Early Classical periods. This Mission shall be achieved through presentation of: • the Annual Bach Festival, • the Visiting Artists Series, and • the Choral Masterworks Series. In addition, the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. shall present a variety of educational and community outreach programs to encourage youth participation in music at all levels, to provide access to constituencies with special needs, and to participate with the community in celebrations or memorials at times of significant special occasions. Adopted by a Resolution of the Bach Festival Society Board of Trustees The Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. is a private non-profit foundation as defined under Section 509(a)(2) of the Internal Revenue Code and is exempt from federal income taxes under IRC Section 501(c)(3). Gifts and contributions are deductible for federal income tax purposes as provided by law. A copy of the Bach Festival Society official registration (CH 1655) and financial information may be obtained from the Florida Division of Consumer Services by calling toll-free 1-800-435-7352 within the State. Registration does not imply endorsement, approval, or recommendation by the State. -

Considerations for Choosing and Combining Instruments

CONSIDERATIONS FOR CHOOSING AND COMBINING INSTRUMENTS IN BASSO CONTINUO GROUP AND OBBLIGATO INSTRUMENTAL FORCES FOR PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED SACRED CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Park, Chungwon Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 04:28:57 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194278 CONSIDERATIONS FOR CHOOSING AND COMBINING INSTRUMENTS IN BASSO CONTINUO GROUP AND OBBLIGATO INSTRUMENTAL FORCES FOR PERFORMANCE OF SELECTED SACRED CANTATAS OF JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH by Chungwon Park ___________________________ Copyright © Chungwon Park 2010 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Music In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College The UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2010 2 UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Chungwon Park entitled Considerations for Choosing and Combining Instruments in Basso Continuo Group and Obbligato Instrumental Forces for Performance of Selected Sacred Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach and recommended that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________________Date: 5/15/2010 Thomas Cockrell Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Rethinking J.S. Bach's Musical Offering

Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Anatoly Milka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3706-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3706-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... vii List of Schemes ....................................................................................... viii List of Music Examples .............................................................................. x List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xiii Preface ...................................................................................................... xv Introduction ............................................................................................... -

Chelsea Grad Set to Run in Ic ' * •' • I' »; ' I^Wayfro.M'at|Antatd^Altl Ake Through 46 .States and 126 U.S

•^>\L-.'1TS^*^t^^*1^;.C^' kf ("''',r**" '•"'*.•• •<--•»--"•-!•»-» • ..^.^...r'j,,*... • *. »».-,..„.,... ^»»v."p,»» •»»»••*?>• ^-.-.^.-.^.,.^^^^..^-,^.-1.11.*^^.».. .^..*n m*»jy«*«**'''f<i'***>(','*'*<"1 '..l**- ,vi. rt/>*,•*>««»•»•Ai»n»*ii*^/ V f ^i«»*rf.¥J'»«*'*^*.^'.'C- .iir.i.Hrrrnu'w^**.','*".J -...***.?/*. «..« />->^^-^w ! ; fl • -**•• -** •O'A'' V ** ^fc"* — *- ,,/4 . J+*»JT. ^^^ * "* '''" "•" "'""• ^ ••'-:v.-~; »r^ »v: v-^lV^;,v:_,,^ , ..-0--.-..^(( JW* 4 2£*a* 4. r^ *** * 5£ wit* * Ul "" * » aiat> i C< 'X I ^ «»-4 •* iS"**' i W af • * * 00 c tf" SO i *«4 » » «1 75' ONI HUNOnn) IHIfill! lit YL.AR - No 29 Chelsea, Michigan, Thursday, December 6. 20(11 32 P^oes Tr S >\-?V ir' "' lr • Festival of Lights Barrage is sold out 'Ow Wight's concert at • Developer waiting for meeting after making some Chelsea High School featur site plan approval. changes to the plan. The com ing the Chelsea House mission meets at 7:30 p.m. the Orchestra and the Celtic By Will Keeler- fourth Thursday of the month at group Barrage has sold out. Staff Writer / the Township Halt. AH 850 tickets were sold, More than 100 acres of farm The developer is looking at said Chelsea House Orchestra land at the south end of the vil changes to the entrance and exit publicist Nancy Fritzemeier. lage limits soon could be devel Ways, of the housing project. She hopes to,arrange another oped into an area with manufac Currently, the only way for traf Concert at a nin|r©liate.^ tured homes. fic to enter is through Brown Students to offer gift The land, located in Sylvan Drive. wrapping Dec 15 Township, is bordered by M-52. -

Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759)

Georg Friedrich Händel (1685-1759) Sämtliche Werke / Complete works in MP3-Format Details Georg Friedrich Händel (George Frederic Handel) (1685-1759) - Complete works / Sämtliche Werke - Total time / Gesamtspielzeit 249:50:54 ( 10 d 10 h ) Titel/Title Zeit/Time 1. Opera HWV 1 - 45, A11, A13, A14 116:30:55 HWV 01 Almira 3:44:50 1994: Fiori musicali - Andrew Lawrence-King, Organ/Harpsichord/Harp - Beate Röllecke Ann Monoyios (Soprano) - Almira, Patricia Rozario (Soprano) - Edilia, Linda Gerrard (Soprano) - Bellante, David Thomas (Bass) - Consalvo, Jamie MacDougall (Tenor) - Fernando, Olaf Haye (Bass) - Raymondo, Christian Elsner (Tenor) - Tabarco HWV 06 Agrippina 3:24:33 2010: Akademie f. Alte Musik Berlin - René Jacobs Alexandrina Pendatchanska (Soprano) - Agrippina, Jennifer Rivera (Mezzo-Soprano) - Nerone, Sunhae Im (Soprano) - Poppea, Bejun Mehta (Counter-Tenor) - Ottone, Marcos Fink (Bass-Bariton) - Claudio, Neal Davis (Bass-Bariton) - Pallante, Dominique Visse (Counter-Tenor) - Narciso, Daniel Schmutzhard (Bass) - Lesbo HWV 07 Rinaldo 2:54:46 1999: The Academy of Ancient Music - Christopher Hogwood Bernarda Fink (Mezzo-Sopran) - Goffredo, Cecilia Bartoli (Mezzo-Sopran) - Almirena, David Daniels (Counter-Tenor) - Rinaldo, Daniel Taylor (Counter-Tenor) - Eustazio, Gerald Finley (Bariton) - Argante, Luba Orgonasova (Soprano) - Armida, Bejun Mehta (Counter-Tenor) - Mago cristiano, Ana-Maria Rincón (Soprano) - Donna, Sirena II, Catherine Bott (Soprano) - Sirena I, Mark Padmore (Tenor) - Un Araldo HWV 08c Il Pastor fido 2:27:42 1994: Capella -

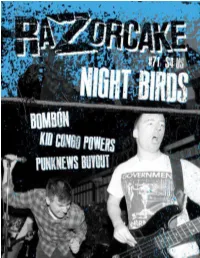

Razorcake Issue

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Curious about how to realistically help Razorcake? If you wish to donate through the mail, please rip this page out and send it to: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. PO Box 42129 Los Angeles, CA 90042 Just NAME: turn ADDRESS: the EMAIL: page. DONATION AMOUNT: 5D]RUFDNH*RUVN\3UHVV,QFD&DOLIRUQLDQRWIRUSUR¿WFRUSRUDWLRQLVUHJLVWHUHG DVDFKDULWDEOHRUJDQL]DWLRQZLWKWKH6WDWHRI&DOLIRUQLD¶V6HFUHWDU\RI6WDWHDQGKDV EHHQJUDQWHGRI¿FLDOWD[H[HPSWVWDWXV VHFWLRQ F RIWKH,QWHUQDO5HYHQXH &RGH IURPWKH8QLWHG6WDWHV,562XUWD[,'QXPEHULV <RXUJLIWLVWD[GHGXFWLEOHWRWKHIXOOH[WHQWSURYLGHGE\ODZ SUBSCRIBE AND HELP KEEP RAZORCAKE IN BUSINESS Subscription rates for a one year, six-issue subscription: U.S. – bulk: $16.50 • U.S. – 1st class, in envelope: $22.50 Prisoners: $22.50 • Canada: $25.00 • Mexico: $33.00 Anywhere else: $50.00 (U.S. funds: checks, cash, or money order) We Do Our Part www.razorcake.org Name Email Address City State Zip U.S. subscribers (sorry world, int’l postage sucks) will receive either Grabass Charlestons, Dale and the Careeners CD (No Idea) or the Awesome Fest 666 Compilation (courtesy of Awesome Fest). Although it never hurts to circle one, we can’t promise what you’ll get. Return this with your payment to: Razorcake, PO Box 42129, LA, CA 90042 If you want your subscription to start with an issue other than #72, please indicate what number. TEN NEW REASONS TO DONATE TO RAZORCAKE VPDQ\RI\RXSUREDEO\DOUHDG\NQRZRazorcake ALVDERQDILGHQRQSURILWPXVLFPDJD]LQHGHGLFDWHG WRVXSSRUWLQJLQGHSHQGHQWPXVLFFXOWXUH$OOGRQDWLRQV The Donation Incentives are… -

Thursdays at Noon: Judy Loman, Harp and Nora Shulman, Flute

Thursdays at Noon: Judy Loman, harp and Nora Shulman, flute Thursday, January 31, 2019 at 12:10 pm Walter Hall, 80 Queen’s Park PROGRAM Chanson de Matin, Op. 15 No. 2 Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Sonata for Flute and Harp Adrian Grigor’yevich Shaposhnikov (1887-1967) i. Andante con moto-Allegro non troppo ii. Menuetto iii. Allegro molto Sonata for flute and harp, Op. 56 Lowell Liebermann (b. 1961) Histoire du Tango Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) i. Bordel 1900 ii. Cafe 1930 iii. Night Club 1960 Follow @UofTMusic The Faculty of Music is a partner of the Bloor St. Culture Corridor Visit www.music.utoronto.ca bloorstculturecorridor.com We wish to acknowledge this land on which the University of Toronto operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional land of the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. Today, this meeting place is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work on this land. BIOGRAPHIES Recognized as one of the world’s of Toronto, and instructor of harp at the Royal Conservatory of foremost harp virtuosos, Judy Music in Toronto. She gives master-classes worldwide and has Loman graduated from the adjudicated at the International Harp Contest in Israel, the USA Curtis Institute of Music, where International Harp Contest and The Vera Dulova International she studied with the celebrated Harp Competition in Moscow. harpist, Carlos Salzedo. She became Principal Harpist with Ms. Loman is a Fellow of the Royal Conservatory and was the Toronto Symphony in 1960.