JS Bach's Chaconne in D Minor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

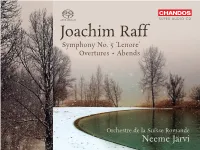

Joachim Raff Symphony No

SUPER AUDIO CD Joachim Raff Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ Overtures • Abends Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Neeme Järvi © Mary Evans Picture Library Picture © Mary Evans Joachim Raff Joachim Raff (1822 – 1882) 1 Overture to ‘Dame Kobold’, Op. 154 (1869) 6:48 Comic Opera in Three Acts Allegro – Andante – Tempo I – Poco più mosso 2 Abends, Op. 163b (1874) 5:21 Rhapsody Orchestration by the composer of the fifth movement from Piano Suite No. 6, Op. 163 (1871) Moderato – Un poco agitato – Tempo I 3 Overture to ‘König Alfred’, WoO 14 (1848 – 49) 13:43 Grand Heroic Opera in Four Acts Andante maestoso – Doppio movimento, Allegro – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto, quasi Tempo I – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto – Andante maestoso 4 Prelude to ‘Dornröschen’, WoO 19 (1855) 6:06 Fairy Tale Epic in Four Parts Mäßig bewegt 5 Overture to ‘Die Eifersüchtigen’, WoO 54 (1881 – 82) 8:25 Comic Opera in Three Acts Andante – Allegro 3 Symphony No. 5, Op. 177 ‘Lenore’ (1872) 39:53 in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur Erste Abtheilung. Liebesglück (First Section. Joy of Love) 6 Allegro 10:29 7 Andante quasi Larghetto 8:04 Zweite Abtheilung. Trennung (Second Section. Separation) 8 Marsch-Tempo – Agitato 9:13 Dritte Abtheilung. Wiedervereinigung im Tode (Third Section. Reunion in Death) 9 Introduction und Ballade (nach G. Bürger’s ‘Lenore’). Allegro – Un poco più mosso (quasi stretto) 11:53 TT 80:55 Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Bogdan Zvoristeanu concert master Neeme Järvi 4 Raff: Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ / Overtures / Abends Symphony No. 5 in E major, Op. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

ONYX4106.Pdf

DOMENICO SCARLATTI (1685–1757) Sonatas and transcriptions 1 Scarlatti: Sonata K135 in E 4.03 2 Scarlatti/Tausig: Sonata K12 in G minor 4.14 3 Scarlatti: Sonata K247 in C sharp minor 4.39 4 Scarlatti/Friedman: Gigue K523 in G 2.20 5 Scarlatti: Sonata K466 in F minor 7.25 6 Scarlatti/Tausig: Sonata K487 in C 2.41 7 Scarlatti: Sonata K87 in B minor 4.26 8 Gieseking: Chaconne on a theme by Scarlatti (Sonata K32) 6.43 9 Scarlatti: Sonata K96 in D 3.52 10 Scarlatti/Tausig: Pastorale (Sonata K9) in E minor 3.49 11 Scarlatti: Sonata K70 in B flat 1.42 12 Scarlatti/Friedman: Pastorale K446 in D 5.09 13 Scarlatti: Sonata K380 in E 5.57 14 Scarlatti/Tausig: Sonata K519 in F minor 2.54 15 Scarlatti: Sonata K32 in D minor 2.45 Total timing: 62.40 Joseph Moog piano Domenico Scarlatti’s legacy of 555 sonatas for harpsichord represent a vast treasure trove. His works fascinate through their originality, their seemingly endless richness of invention, their daring harmonics and their visionary use of the most remote tonalities. Today Scarlatti has once again established a firm place in the pianistic repertory. But the question preoccupying me was the influence his music had on the composers of the Romantic era. If we cast an eye over the countless recordings of transcriptions and arrangements of his contemporary Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), it becomes even clearer that in Scarlatti’s case, we find hardly anything comparable. A fascinating process of investigation eventually led me to Carl Tausig (1841–1871), Ignaz Friedman (1882–1948) and Walter Gieseking (1895–1956). -

Spread the Word • Promote the Show

Program No. 1409 3/3/2014 E. T. PAULL: Napoleon’s Last Charge –Nathan BACH: Trio Sonata No. 2 in c, BWV 526 –Edie Sibling Rivals . though Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Avakian (1928 Kimball/Cleveland High School Johnson (1998 Fisk/Furman University, Greenville, was reputed the finest organist of his era, he died penniless Auditorium, Portland, OR) Avakian Creative SC) Pipedreams Archive (r. 1/27/11) while his younger brother, Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach, Works 709-01 J. S. BACH: Prelude & Fugue in e, BWV 548 – prospered as harpsichordist to Frederick the Great and DAVID FULLER: The Fifty-Years March – Wyatt Smith (2010 Schantz/Martin Luther College, later as Music Director for the city of Hamburg. Christopher Howerther (1990 Fisk/Slee Hall, New Ulm, MN) Pipedreams Archive (r. 2/12/12) SUNY-Buffalo, NY) Pipedreams Archive W.F. BACH: Fantasie in d –Friedhelm Flamme BACH: Ricercare a 6, fr The Musical Offering, CHARLES-MARIE WIDOR: Marche Nuptiale – BWV 1079 –Michel Bouvard (1987 Kney/Uni- (2008 Hillebrand/Münsterkirche St. Alexandri, Herman van Vliet (1890 Cavaillé-Coll/St. Ouen, Einbeck, Germany) cpo 777.527 versity of St. Thomas, Saint Paul, MN) Pipedreams Rouen, France) Festivo 149 Archive (r. 3/17/13) C.P.E. BACH: Sonata No. 1 in A, Wq 70, no. 1 – J. P. SOUSA (arr. Faxon): The Stars and Stripes Roland Münch (1755 Marx/Evangelical Church Forever –Erik Suter & Scott Hanoian (Aeolian- Program No. 1412 3/24/2014 ‘Zur frohen Botschaft’, Berlin-Karlshorst, Skinner/Washington National Cathedral, DC) Conventional Wisdom: A Chicago Collection Germany) Christophorus 0110-2 WNC 501 . unique recital performances from the 2006 W.F. -

Three BJ S-Three Chaconnes Byron Cantrell

Three BJ s-Three Chaconnes Byron Cantrell Ever since Hans von Bulow coined the expression "the three B's" in denoting J. S. Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms to the exclusion of other fine composers whose family names begin with that same initial letter, numerous comparisons have been made regarding the composition techniques of these masters. Although distinct forms are associated with the different time periods within which each lived, all three of these men are regarded as superior composers of variations. Each has treated the usual melodico-harmonic forms so idiomatically that commentary is too often limited to banal remarks on similarities or non- comparative discussion of individual works. The continuous variation form, the chaco nne, has, however, been ingeniously used by these three masters, and, because most of the aspects of the form are demonstrably retained by each of them, comparisons can effectively be made. Emerging in the late Renaissance, the chaconne gained enormous popu- larity during the Baroque era; indeed, no opera in the Italian style was considered complete during this age without one or more numbers in chaconne form. But with the Classical period came a strong preference for melodico-harmonic variations and opera buffa finales, and the ostinato variation idea seemed destined for oblivion. It was Johannes Brahms, late in the Romantic period, who handsomely revived the chaconne and thus paved the way for its popularity among later composers. In his book, The Technique of Variation, Dr. Robert U. Nelson devotes considerable space to a discussion of Baroque chaco nne practice in the instrumental field. In order to consider the three pieces selected for study here, a list of fourteen points has been extracted from Dr. -

CENTURY ORGAN MUSIC for the Degree of MASTER of MUSIC By

ol 0002 -T-E CHACONNE AND PASSACAGLIA IN TVVENTIETH CENTURY ORGAN MUSIC THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By U3arney C. Tiller, Jr., B. M., B. A. Denton, Texas January, 1966 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . II. THE HISTORY OF THE CHACONNE AND PASSACAGLIA . 5 III. ANALYSES OF SEVENTEEN CHACONNES AND PASSACAGLIAS FROM THE TWENTIETH CENTURY. 34 IV. CONCLUSIONS . 116 APPENDIX . 139 BIBLIOGRAPHY. * . * . * . .160 iii LIST OF TABLES Table Page I. Grouping of Variations According to Charac- teristics of Construction in the Chaconne by Brian Brockless. .. 40 TI. Thematic Treatment in the Chaconne from the Prelude, Toccata and Chaconne by Brian Brockless. .*0 . 41 III. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Passacaglia and Fugue by Roland Diggle. 45 IV. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Moto Continuo and Passacglia by 'Herbert F. V. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction and Passacaglia by Alan Gray . $4 VI. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction and Passacaglia b Robert . .*. -...... .... $8 Groves * - 8 VII. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia by Ellis B. Kohs . 64 VIII. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction and Passaglia in A Minor by C. S. Lang . * . 73 IX. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Passaca a andin D Minor by Gardner Read * . - - *. -#. *. 85 X. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction, Passacgland ugue by Healey Willan . 104 XI. Thematic Treatment in the Passacaglia from the Introduction, Passacaglia and F by Searle Wright . -

A/L CHOPIN's MAZURKA

17, ~A/l CHOPIN'S MAZURKA: A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF J. S. BACH--F. BUSONI, D. SCARLATTI, W. A. MOZART, L. V. BEETHOVEN, F. SCHUBERT, F. CHOPIN, M. RAVEL AND K. SZYMANOWSKI DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial. Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Jan Bogdan Drath Denton, Texas August, 1969 (Z Jan Bogdan Drath 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . I PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS First Recital . , , . ., * * 4 Second Recital. 8 Solo and Chamber Music Recital. 11 Lecture-Recital: "Chopin's Mazurka" . 14 List of Illustrations Text of the Lecture Bibliography TAPED RECORDINGS OF PERFORMANCES . Enclosed iii INTRODUCTION This dissertation consists of four programs: one lec- ture-recital, two recitals for piano solo, and one (the Schubert program) in combination with other instruments. The repertoire of the complete series of concerts was chosen with the intention of demonstrating the ability of the per- former to project music of various types and composed in different periods. The first program featured two complete sets of Concert Etudes, showing how a nineteenth-century composer (Chopin) and a twentieth-century composer (Szymanowski) solved the problem of assimilating typical pianistic patterns of their respective eras in short musical forms, These selections are preceded on the program by a group of compositions, consis- ting of a. a Chaconne for violin solo by J. S. Bach, an eighteenth-century composer, as. transcribed for piano by a twentieth-century composer, who recreated this piece, using all the possibilities of modern piano technique, b. -

Raff's Arragement for Piano of Bach's Cello Suites

Six Sonatas for Cello by J.S.Bach arranged for the Pianoforte by JOACHIM RAFF WoO.30 Sonata No.1 in G major Sonate No.2 in D minor Sonate No.3 in C major Sonate No.4 in E flat major Sonate No.5 in C minor Sonate No.6 in D major Joachim Raff’s interest in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and the inspiration he drew from them is unmatched by any of the other major composers in the second half of the 19th century. One could speculate that Raff’s partiality for polyphonic writing originates from his studies of Bach’s works - the identification of “influenced by Bach” with “Polyphony” is a popular idea but is often questionable in terms of scientific correctness. Raff wrote numerous original compositions in polyphonic style and used musical forms of the baroque period. However, he also created a relatively large number of arrangements and transcriptions of works by Bach. Obviously, Bach’s music exerted a strong attraction on Raff that went further than plain admiration. Looking at Raff’s arrangements one can easily detect his particular interest in those works by Bach that could be supplemented by another composer. Upon these models Raff could fit his reverence for the musical past as well as exploit his never tiring interest in the technical aspects of the art of composition. One of the few statements we have by Raff about the basics of his art reveal his concept of how to attach supplements to works by Bach. Raff wrote about his orchestral arrangement of Bach’s Ciaconna in d minor for solo violin: "Everybody who has studied J.S. -

The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music from the Dean

WINTER 2012 The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music From the Dean On behalf of the College of Fine and Applied Arts, I want to congratulate the School of Music on a year of outstanding accomplishments and to WINTER 2012 thank the School’s many alumni and friends who Published for alumni and friends of the School of Music at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. have supported its mission. The School of Music is a unit of the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and has been an accredited institutional member of the National While it teaches and interprets the music of the past, the School is committed Association of Schools of Music since 1933. to educating the next generation of artists and scholars; to preserving our artistic heritage; to pursuing knowledge through research, application, and service; and Karl Kramer, Director Joyce Griggs, Associate Director for Academic Affairs to creating artistic expression for the future. The success of its faculty, students, James Gortner, Assistant Director for Operations and Finance J. Michael Holmes, Enrollment Management Director and alumni in performance and scholarship is outstanding. David Allen, Outreach and Public Engagement Director Sally Takada Bernhardsson, Director of Development Ruth Stoltzfus, Coordinator, Music Events The last few years have witnessed uncertain state funding and, this past year, deep budget cuts. The challenges facing the School and College are real, but Tina Happ, Managing Editor Jean Kramer, Copy Editor so is our ability to chart our own course. The School of Music has resolved to Karen Marie Gallant, Student News Editor Contributing Writers: David Allen, Sally Takada Bernhardsson, move forward together, to disregard the things it can’t control, and to succeed Michael Cameron, Tina Happ, B. -

A Structural Analysis of the Relationship Between Programme, Harmony and Form in the Symphonic Poems of Franz Liszt Keith Thomas Johns University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 A structural analysis of the relationship between programme, harmony and form in the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt Keith Thomas Johns University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Johns, Keith Thomas, A structural analysis of the relationship between programme, harmony and form in the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1927 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PROGRAMME, HARMONY AND FORM IN THE SYMPHONIC POEMS OF FRANZ LISZT. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from THE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by KEITH THOMAS JOHNS (M.Litt.,B.A.Hons.,Grad.Dip.Ed., F.L.C.M., F.T.C.L., L.T.C.L. ) SCHOOL OF CREATIVE ARTS 1986 i ABSTRACT This thesis examines the central concern in an analysis of the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt, that is, the relationship between programme,harmony and form. In order to make a thorough and clear analysis of this relationship a structural/semiotic analysis has been developed as the analysis of best fit. Historically it has been fashionable to see Liszt's symphonic poems in terms of sonata form or a form only making sense in terms of the attached programme. Both of these ideas are critically examined in this analysis. -

Ferruccio Busoni – the Six Sonatinas: an Artist’S Journey 1909-1920 – His Language and His World

Ferruccio Busoni – The Six Sonatinas: An Artist’s Journey 1909-1920 – his language and his world Jeni Slotchiver This is the concluding second Part of the author’s in-depth appreciation of these greatly significant piano works. Part I was published in our issue No 1504 July- September 2015. t summer’s end, 1914, Busoni asks for artists in exile from Europe. Audiences are A a year’s leave of absence from his in thin supply. He writes to Edith Andreae, position as director of the Liceo Musicale June 1915, “I didn’t dare set to work on in Bologna. He signs a contract for his the opera… for fear that a false start American tour and remains in Berlin over would destroy my last moral foothold.” Christmas, playing a Bach concert to Busoni begins an orchestral comp- benefit charities. This is the first all-Bach osition as a warm-up for Arlecchino, the piano recital for the Berlin public, and Rondò Arlecchinesco. He sets down ideas, Dent writes that it is received with hoping they might be a useful study, if all “discourteous ingratitude.” Busoni outlines else fails, and writes, “If the humour in the his plan for Dr. Faust, recording in his Rondò manifests itself at all, it will have a diary, “Everything came together like a heartrending effect.” With bold harmonic vision.” By Christmastime, the text is language, Busoni clearly defines this complete. With the outbreak of war in composition as his last experimental work. 1914 and an uncertain future, Busoni sails The years give way to compassionate to New York with his family on 5 January, reflection. -

Rethinking J.S. Bach's Musical Offering

Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev Rethinking J.S. Bach’s Musical Offering By Anatoly Milka Translated from Russian by Marina Ritzarev This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Anatoly Milka All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3706-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3706-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... vii List of Schemes ....................................................................................... viii List of Music Examples .............................................................................. x List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii List of Abbreviations ............................................................................... xiii Preface ...................................................................................................... xv Introduction ...............................................................................................