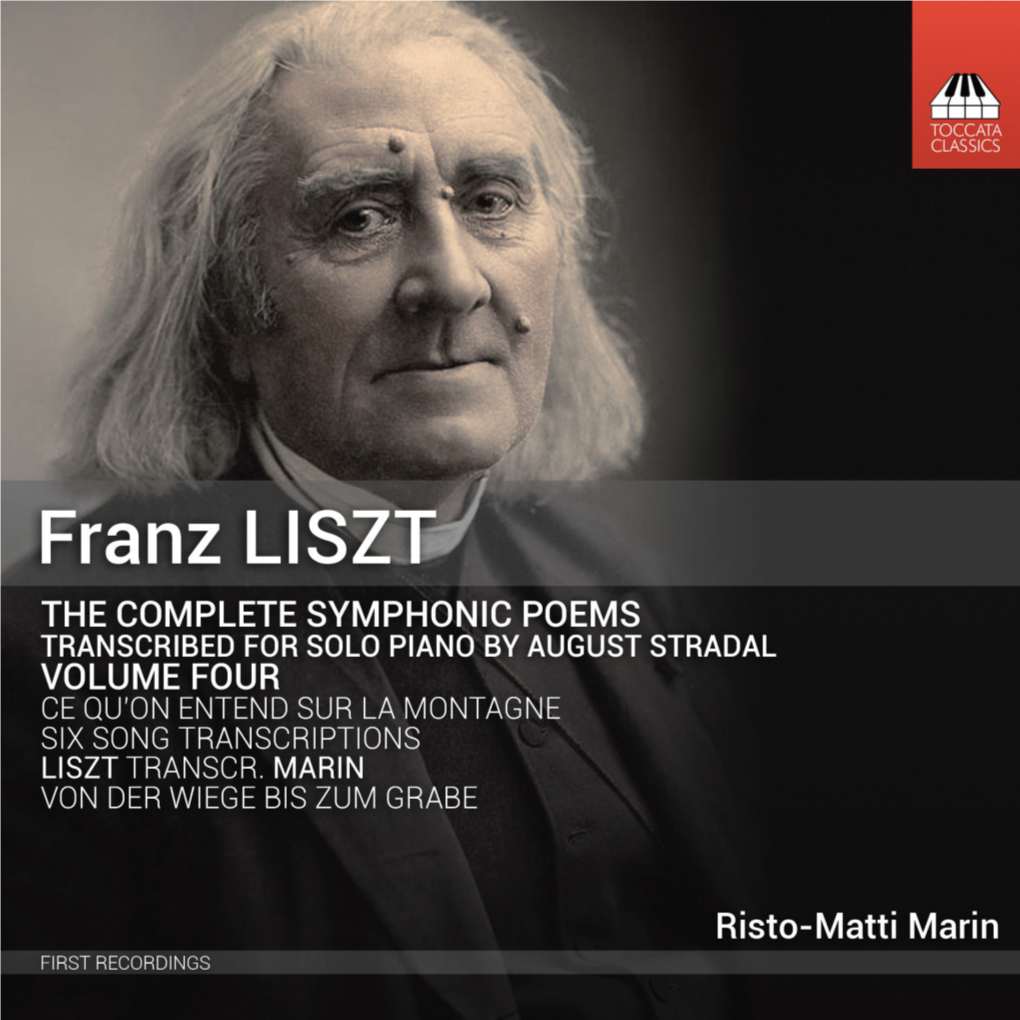

TOCC0517DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joachim Raff Symphony No

SUPER AUDIO CD Joachim Raff Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ Overtures • Abends Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Neeme Järvi © Mary Evans Picture Library Picture © Mary Evans Joachim Raff Joachim Raff (1822 – 1882) 1 Overture to ‘Dame Kobold’, Op. 154 (1869) 6:48 Comic Opera in Three Acts Allegro – Andante – Tempo I – Poco più mosso 2 Abends, Op. 163b (1874) 5:21 Rhapsody Orchestration by the composer of the fifth movement from Piano Suite No. 6, Op. 163 (1871) Moderato – Un poco agitato – Tempo I 3 Overture to ‘König Alfred’, WoO 14 (1848 – 49) 13:43 Grand Heroic Opera in Four Acts Andante maestoso – Doppio movimento, Allegro – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto, quasi Tempo I – Meno moto, quasi Marcia – Più moto – Andante maestoso 4 Prelude to ‘Dornröschen’, WoO 19 (1855) 6:06 Fairy Tale Epic in Four Parts Mäßig bewegt 5 Overture to ‘Die Eifersüchtigen’, WoO 54 (1881 – 82) 8:25 Comic Opera in Three Acts Andante – Allegro 3 Symphony No. 5, Op. 177 ‘Lenore’ (1872) 39:53 in E major • in E-Dur • en mi majeur Erste Abtheilung. Liebesglück (First Section. Joy of Love) 6 Allegro 10:29 7 Andante quasi Larghetto 8:04 Zweite Abtheilung. Trennung (Second Section. Separation) 8 Marsch-Tempo – Agitato 9:13 Dritte Abtheilung. Wiedervereinigung im Tode (Third Section. Reunion in Death) 9 Introduction und Ballade (nach G. Bürger’s ‘Lenore’). Allegro – Un poco più mosso (quasi stretto) 11:53 TT 80:55 Orchestre de la Suisse Romande Bogdan Zvoristeanu concert master Neeme Järvi 4 Raff: Symphony No. 5 ‘Lenore’ / Overtures / Abends Symphony No. 5 in E major, Op. -

Qt7q1594xs.Pdf

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title A Critical Inferno? Hoplit, Hanslick and Liszt's Dante Symphony Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7q1594xs Author Grimes, Nicole Publication Date 2021-06-28 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A Critical Inferno? Hoplit, Hanslick and Liszt’s Dante Symphony NICOLE GRIMES ‘Wie ist in der Musik beseelte Form von leerer Form wissenschaftlich zu unterscheiden?’1 Introduction In 1881, Eduard Hanslick, one of the most influential music critics of the nineteenth century, published a review of a performance of Liszt’s Dante Symphony (Eine Sym- phonie zu Dantes Divina commedia) played at Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde on 14 April, the eve of Good Friday.2 Although he professed to be an ‘admirer of Liszt’, Hanslick admitted at the outset that he was ‘not a fan of his compositions, least of all his symphonic poems’. Having often given his opinion in detail on those works in the Neue Freie Presse, Hanslick promised brevity on this occasion, asserting that ‘Liszt wishes to compose with poetic elements rather than musical ones’. There is a deep genesis to Hanslick’s criticism of Liszt’s compositions, one that goes back some thirty years to the controversy surrounding progress in music and musical aesthetics that took place in the Austro-German musical press between the so-called ‘New Germans’ and the ‘formalists’ in the 1850s. This controversy was bound up not only with music, but with the philosophical positions the various parties held. The debate was concerned with issues addressed in Hanslick’s monograph Vom Musika- lisch-Schönen, first published in 1854,3 and with opinions expressed by Liszt in a series of three review articles on programme music published contemporaneously in the 1 ‘How is form imbued with meaning to be differentiated philosophically from empty form?’ Eduard Hanslick, Aus meinem Leben, ed. -

Brahms Reimagined by René Spencer Saller

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, October 28, 2016 at 10:30AM Saturday, October 29, 2016 at 8:00PM Jun Märkl, conductor Jeremy Denk, piano LISZT Prometheus (1850) (1811–1886) MOZART Piano Concerto No. 23 in A major, K. 488 (1786) (1756–1791) Allegro Adagio Allegro assai Jeremy Denk, piano INTERMISSION BRAHMS/orch. Schoenberg Piano Quartet in G minor, op. 25 (1861/1937) (1833–1897)/(1874–1951) Allegro Intermezzo: Allegro, ma non troppo Andante con moto Rondo alla zingarese: Presto 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. Jun Märkl is the Ann and Lee Liberman Guest Artist. Jeremy Denk is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, October 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Lawrence and Cheryl Katzenstein. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of The Delmar Gardens Family, and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 CONCERT CALENDAR For tickets call 314-534-1700, visit stlsymphony.org, or use the free STL Symphony mobile app available for iOS and Android. TCHAIKOVSKY 5: Fri, Nov 4, 8:00pm | Sat, Nov 5, 8:00pm Han-Na Chang, conductor; Jan Mráček, violin GLINKA Ruslan und Lyudmila Overture PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 1 I M E TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 5 AND OCK R HEILA S Han-Na Chang SLATKIN CONDUCTS PORGY & BESS: Fri, Nov 11, 10:30am | Sat, Nov 12, 8:00pm Sun, Nov 13, 3:00pm Leonard Slatkin, conductor; Olga Kern, piano SLATKIN Kinah BARBER Piano Concerto H S ODI C COPLAND Billy the Kid Suite YBELLE GERSHWIN/arr. -

380 XXXIX. Tonkünstler-Versammlung Basel

380 XXXIX. Tonkünstler-Versammlung Basel, [Karlsruhe], [11.] 12. – 15. Juni 1903 Festdirigenten: Hans Huber, Hermann Suter Festchor: Basler Gesangverein, Basler Liedertafel, Reveillechor der Basler Liedertafel Ens.: Orchester der Allgemeinen Musikgesellschaft Basel, verstärkt durch Mitglieder der Meininger Hofkapelle und des Orchestre symphonique de Lausanne sowie hiesige und auswärtige Künstler (110 Musiker) 1. Aufführung: Festvorstellung Karlsruhe, Großhzgl. Hoftheater, Donnerstag, 11. Juni Friedrich Klose: Das Märlein vom Fischer und seiner Frau, Oper 2. Aufführung: I. Konzert [auch: für Soli, Männerchor und Orchester ] Basel, Musiksaal, Freitag, 12. Juni, 19:00 Uhr 1. Émile Jaques-Dalcroze: Sancho, Comédie lyrique Vorspiel für Orchester 2. Friedrich Hegar: Männerchöre a cappella Ch.: Basler Liedertafel a) Das Märchen vom Mummelsee (Ms.) Text: C.A. Schnezler (≡) b) Walpurga op. 31 Text: Carl Spitteler ( ≡) 3. Ernest Bloch: Symphonie cis-Moll (Ms.) 1. 2. Largo 2. 3. Vivace 4. Max von Schillings: Das Hexenlied, mit begleitender Sol.: Ernst von Possart (Rez.) Musik für Orchester op. 15 Text: Ernst von Wildenbruch 5. Waldemar Pahnke: Concert für Violine und Orchester c- Sol.: Henri Marteau (V.) Moll (Ms.) 1. Moderato con moto 2. Allegro vivace ---- 6. Hans Huber: Caenis (die Verwandlung), für Männerchor, Sol.: Maria Cäcilia Philippi (A) Altsolo und Orchester op. 101 Ch.: Basler Liedertafel Text: Joseph Victor Widmann, nach einer antiken Sage (≡) 7. Gesänge für Bariton mit Orchester Sol.: Richard Koennecke (Bar.) a) Klaus Pringsheim: Venedig Text: Friedrich Nietzsche (≡) Oskar C. Posa: b) Tod in Aehren Text: Detlev von Liliencron (≡) c) „Mit Trommeln und Pfeifen“ (Ms.) Text: Detlev von Liliencron (≡) 8. Ernst Boehe: Aus Odysseus Fahrten, 4 Episoden für grosses Orchester gesetzt op. -

Eine Symphonie Zu Dantes Divina Commedia Deux Légendes

Liszt SYMPHONIC POEMS VOL. 5 Eine Symphonie zu Dantes Divina Commedia Deux Légendes BBC Philharmonic GIANANDREA NOSEDA CHAN 10524 Franz Liszt (1811–1886) Symphonic Poems, Volume 5 AKG Images, London Images, AKG Eine Symphonie zu Dantes Divina Commedia, S 109* 42:06 for large orchestra and women’s chorus Richard Wagner gewidmet I Inferno 20:03 1 Lento – Un poco più accelerando – Allegro frenetico. Quasi doppio movimento (Alla breve) – Più mosso – Presto molto – Lento – 6:31 2 Quasi andante, ma sempre un poco mosso – 5:18 3 Andante amoroso. Tempo rubato – Più ritenuto – 3:42 4 Tempo I. Allegro (Alla breve) – Più mosso – Più mosso – Più moderato (Alla breve) – Adagio 4:32 II Purgatorio 21:57 5 Andante con moto quasi allegretto. Tranquillo assai – Più lento – Un poco meno mosso – 6:22 6 Lamentoso – 5:11 Franz Liszt, steel plate engraving, 1858, by August Weger (1823 –1892) after a photograph 3 Liszt: Symphonic Poems, Volume 5 7 [L’istesso tempo] – Poco a poco più di moto – 3:42 8 Magnificat. L’istesso tempo – Poco a poco accelerando e Deux Légendes published by Editio Musica in Budapest in crescendo sin al Più mosso – Più mosso ma non troppo – TheDeux Légendes, ‘St François d’Assise: la 1984. ‘St François d’Assise’ is scored for strings, Un poco più lento – L’istesso tempo, ma quieto assai 6:40 prédication aux oiseaux’ (St Francis of Assisi: woodwind and harp only, while ‘St François de the Sermon to the Birds) and ‘St François de Paule’ adds four horns, four trombones and a Deux Légendes, S 354 19:10 Paule marchant sur les flots’ (St Francis of bass trombone. -

Raff's Arragement for Piano of Bach's Cello Suites

Six Sonatas for Cello by J.S.Bach arranged for the Pianoforte by JOACHIM RAFF WoO.30 Sonata No.1 in G major Sonate No.2 in D minor Sonate No.3 in C major Sonate No.4 in E flat major Sonate No.5 in C minor Sonate No.6 in D major Joachim Raff’s interest in the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and the inspiration he drew from them is unmatched by any of the other major composers in the second half of the 19th century. One could speculate that Raff’s partiality for polyphonic writing originates from his studies of Bach’s works - the identification of “influenced by Bach” with “Polyphony” is a popular idea but is often questionable in terms of scientific correctness. Raff wrote numerous original compositions in polyphonic style and used musical forms of the baroque period. However, he also created a relatively large number of arrangements and transcriptions of works by Bach. Obviously, Bach’s music exerted a strong attraction on Raff that went further than plain admiration. Looking at Raff’s arrangements one can easily detect his particular interest in those works by Bach that could be supplemented by another composer. Upon these models Raff could fit his reverence for the musical past as well as exploit his never tiring interest in the technical aspects of the art of composition. One of the few statements we have by Raff about the basics of his art reveal his concept of how to attach supplements to works by Bach. Raff wrote about his orchestral arrangement of Bach’s Ciaconna in d minor for solo violin: "Everybody who has studied J.S. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

A Performer's Analysis of Liszt's Sonetto 47 Del Petrarca

A PERFORMER’S ANALYSIS OF LISZT’S SONETTO 47 DEL PETRARCA A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PIANO PERFORMANCE AND PEDAGOGY BY SHUANG CHEN DR. LORI RHODEN - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2013 Liszt was born in the part of western Hungary that became known today as the Burgenland. As one of the leaders of the Romantic movement in music, Liszt developed new methods of piano performance and composition; he anticipated the ideas/procedures of music in the 20th century. He also promoted the method of thematic transformation as part of his revolution in form, made radical experiments in harmony, and invented the symphonic poem for orchestra. He was a composer, teacher and most importantly, a highly accomplished pianist. As one of the greatest piano virtuosos of his time, he had excellent technique and a dazzling performance ability that gained him fame and enabled the spreading of the knowledge of other composers’ music. He was also committed to preserving and promoting the best music from the past, including Bach, Handel, Schubert, Weber and Beethoven. Liszt had a strong religious background, which was contradictory to his love for worldly sensationalism. It is fair, however, to say that he was a great man who had a positive influence on people around him. From the 1830-1840’s, Liszt developed a new vocabulary for technique and musical expression in the piano world. He was able to do so partly because of the advances in the mechanical construction of the instrument. -

A Structural Analysis of the Relationship Between Programme, Harmony and Form in the Symphonic Poems of Franz Liszt Keith Thomas Johns University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 A structural analysis of the relationship between programme, harmony and form in the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt Keith Thomas Johns University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Johns, Keith Thomas, A structural analysis of the relationship between programme, harmony and form in the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1927 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PROGRAMME, HARMONY AND FORM IN THE SYMPHONIC POEMS OF FRANZ LISZT. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from THE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by KEITH THOMAS JOHNS (M.Litt.,B.A.Hons.,Grad.Dip.Ed., F.L.C.M., F.T.C.L., L.T.C.L. ) SCHOOL OF CREATIVE ARTS 1986 i ABSTRACT This thesis examines the central concern in an analysis of the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt, that is, the relationship between programme,harmony and form. In order to make a thorough and clear analysis of this relationship a structural/semiotic analysis has been developed as the analysis of best fit. Historically it has been fashionable to see Liszt's symphonic poems in terms of sonata form or a form only making sense in terms of the attached programme. Both of these ideas are critically examined in this analysis. -

Riccardo Muti Conductor Michele Campanella Piano Eric Cutler Tenor Men of the Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe Director Wagne

Program ONE huNdrEd TwENTy-FirST SEASON Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Friday, September 30, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, October 1, 2011, at 8:00 Tuesday, October 4, 2011, at 7:30 riccardo muti conductor michele Campanella piano Eric Cutler tenor men of the Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe director Wagner Huldigungsmarsch Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major Allegro maestoso Quasi adagio— Allegretto vivace— Allegro marziale animato MiChElE CampanellA IntErmISSIon Liszt A Faust Symphony Faust: lento assai—Allegro impetuoso Gretchen: Andante soave Mephistopheles: Allegro vivace, ironico EriC CuTlEr MEN OF ThE Chicago SyMPhONy ChOruS This concert series is generously made possible by Mr. & Mrs. Dietrich M. Gross. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra thanks Mr. & Mrs. John Giura for their leadership support in partially sponsoring Friday evening’s performance. CSO Tuesday series concerts are sponsored by United Airlines. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PhilliP huSChEr ne hundred years ago, the Chicago Symphony paid tribute Oto the centenary of the birth of Franz Liszt with the pro- gram of music Riccardo Muti conducts this week to honor the bicentennial of the composer’s birth. Today, Liszt’s stature in the music world seems diminished—his music is not all that regularly performed, aside from a few works, such as the B minor piano sonata, that have never gone out of favor; and he is more a name in the history books than an indispensable part of our concert life. -

Rezensionen Für

Rezensionen für Franz Liszt: Künstlerfestzug - Tasso - Dante Symphony aud 97.760 4022143977601 allmusic.com 01.04.2020 ( - 2020.04.01) source: https://www.allmusic.com/album/franz-lis... Karabits's performance of this large work is several minutes longer than average, without dragging in the least: he gets the moody quality that is lost in splashier readings. A very strong Liszt release, with fine sound from the Congress Centrum Neue Weimarhalle. Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. American Record Guide August 2020 ( - 2020.08.01) In 1847 while touring as a pianist in Kiev, Liszt met Polish Princess Carolyne of Sayn–Wittgenstein, who became his companion for the rest of his life. In 1848 he accepted a conducting job in Weimar, where he and the Princess lived until 1861. Carolyne persuaded him to trade performing for composing, and those years, among his most prolific, produced the three works on this program. As a young man, Liszt was already an admirer of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. In the 1840s he considered writing a chorus and orchestra work drawn from it, accompanied by a slideshow of scenes from the poem by German artist Bonaventura Genelli, but nothing came of it. In 1849, he composed Apres une Lecture du Dante: Fantasia quasi Sonata (the Dante Sonata) for piano. In 1855 he began the Dante Symphony based on the 'Inferno' and 'Purgatorio' sections of Dante's poem. He completed it in 1857. The work begins with Virgil and Dante descending into the Inferno. Liszt supplied no text save for the Magnificat, but he included a few lines from the poem under score staves to guide the conductor's interpretation, most notably the opening brass motifs to the rhythms of the text over the Gates of Hell. -

Neeme Järvi Highlights from a Remarkable 30-Year Recording Career Neeme Järvi Järvi Neeme

NEEME JÄRVI Highlights from a remarkable 30-year recording career Neeme Järvi © Tiit Veermäe / Alamy Neeme Järvi (b. 1937) Highlights from a remarkable 30-year recording career COMPACT DISC ONE Antonín Dvořák (1841 – 1904) 1 Carnival, Op. 92 (B 169) 9:04 Concert Overture Scottish National Orchestra (CHAN 9002 – download only) Johan Halvorsen (1864 – 1935) 2 La Mélancolie 2:27 Mélodie de Ole Bull (1810 – 1880) Melina Mandozzi violin Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra (CHAN 10584) Antonín Dvořák 3 Slavonic Dance in E minor, Op. 72 (B 147) No. 2 5:30 Second Series Scottish National Orchestra (CHAN 6641) 3 Gustav Mahler (1860 – 1911) 4 Nun seh’ ich wohl, warum so dunkle Flammen 4:52 No. 2 from Kindertotenlieder Linda Finnie mezzo-soprano Scottish National Orchestra (CHAN 9545 – download only) Franz von Suppé (1819 – 1895) 5 March from ‘Fatinitza’ 2:26 Royal Scottish National Orchestra (not previously released) Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897) 6 Hungarian Dance No. 19 in B minor 2:23 Orchestrated by Antonín Dvořák London Symphony Orchestra (CHAN 10073 X) Ferruccio Busoni (1866 – 1924) 7 Finale from ‘Tanzwalzer’, Op. 53 4:03 BBC Philharmonic (CHAN 9920) 4 Giovanni Bolzoni (1841 – 1919) 8 Minuetto 3:58 Detroit Symphony Orchestra (CHAN 6648) Zoltán Kodály (1882 – 1967) 9 Intermezzo from ‘Háry János Suite’ 5:03 Laurence Kaptain cimbalom Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CHAN 8877) Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937) 10 La Valse 12:07 Poème chorégraphique pour orchestre Detroit Symphony Orchestra (CHAN 6615) Johann Severin Svendsen (1840 – 1911) 11 Träume 3:45 Studie zu Tristan und Isolde Arrangement of No. 5 from Fünf Gedichte für eine Frauenstimme (‘Wesendonck Lieder’) by Richard Wagner Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra (CHAN 10693) 5 Richard Strauss (1864 – 1949) 12 Morgen! 4:03 No.