Hystra Full Report (2011) Access to Safe Water.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II

OFFICIAL USE ONLY IDA/SecM2007-0684 December 12, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized For meeting of Board: Tuesday, January 8, 2008 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Guinea: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note 1. Attached is the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II. The IMF is currently scheduled to discuss this document on December 21, 2007. 2. The PRSP II was prepared by the Government of Guinea. The paper acknowledges the disappointing outcome of the first PRSP, which covered the period 2002-2006. The political, social and economic environment in which the implementation of PRSP I took place was characterized by poor governance, political instability, and low growth which led to an increase in poverty from 49 percent in 2002 to an estimated 54 percent in 2005. Overall, public service delivery deteriorated in terms of both quality and access and the living conditions for most Guineans worsened. Public Disclosure Authorized 3. PRSP II aims at recapturing lost ground over the past five years. The overall strategy is based on three pillars: (i) improving governance; (ii) accelerating growth and increasing employment opportunities; and (iii) improving access to basic services. It focuses on restoring macroeconomic stability, institutional and structural reforms, and mechanisms to strengthen the democratic process implementation capacity. 4. As approved by the Board on August 6, 2007, the pilot Board Technical Questions and Answer Database (http://boardqa.worldbank.org or from the EDs' portal) is now open for questions. -

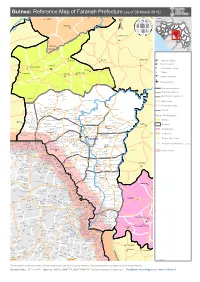

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (As of 05 March 2015)

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (as of 05 March 2015) Kalinko SENEGAL MALI GUINEA Sélouma BISSAU GUINEA Komola Koura COTE D'IVOIRE SIERRA LEONE Dialakoro Kankama LIBERIA Sisséla Sanguiana Bissikirima Regional Capital District Capital Dabola Arfamoussayah Sub District Capital Banko Kounendou Village Dogomet N'demba Unpaved runway Paved runway Region boundaries Koulambo District boundaries Morigbeya Dar Es Salam Daro Gada Walan Sub District boundaries Kindoyé DIGUILA CENTRE Fabouya TOUMANIA CENTRE Boubouya Main roads Yombo Nialen Moria Dansoya Secondary roads NIENOUYA CENTRE Teliayaga Doukou Passaya Souriya Mansira Moribaya KONDEBOU KASSA BOUNA CENTRE Tambaya Rivers Foya Gadha Mongoli Babakadia Hafia Gomboya BELEYA CENTRE SABERE KALIA Keema SOUNGBANYA CENTRE Balandou Beindougou SANSANKO CENTRE Sidakoro Gueagbely Gueafari Sokora District (Préfectures) Harounaya Miniandala Badhi Gnentin Oussouya Banire Wolofouga Lamiya Gueagbely Mameyire SANSAMBOU CENTRE BIRISSA CENTRE NGUENEYA CENTRE NIAKO CENTRE Koumandi Koura Dabola Wassakaria Kobalen Bingal Dansoya Tomata Konkofaya Heredou Marela karimbou Sansamba Bouran SOLOYA CENTRE Kolmatamba KOUMANDI KORO Sanamoussaya MILIDALA CENTRE Banfele Labatara Gninantamba BONTALA Koura Sambouya DIANA CENTRE Sansando Faranah Wossekalia FRIGUIA CENTRE MAGNA Halossagoya KALIA CENTRE I KOMBONYA Ballayany Herewa Alia Filly Fore Sakoromaya SOLONYEREYA Khamaya Bindou Dansaya Koutamodiya Salia Kamako Kissidougou Goulouya Fantoumaniya Nerekoro SEREKORO CENTRE Guidonya Kombonyady Wassambala Balankhamba Kabaya -

Sierra Leone – Prospects for Peace Severely Compromised

CONSOLIDATED INTER-AGENCY APPEALS FOR 2001 UNITED NATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL COPIES, PLEASE CONTACT: UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS PALAIS DES NATIONS 8-14 AVENUE DE LA PAIX CH - 1211 GENEVA, SWITZERLAND TEL.: (41 22) 917.1972 FAX: (41 22) 917.0368 E-MAIL: [email protected] THIS DOCUMENT CAN ALSO BE FOUND ON http://www.reliefweb.int/ TABLE OF CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 TABLE I :TOTAL FUNDING REQUIREMENTS - BY AGENCY AND COUNTRY ........................................3 TABLE II: SUMMARY OF REQUIREMENTS BY SECTOR AND APPEALING AGENCY............................4 SUB-REGIONAL OVERVIEW......................................................................................................... 5 1. Background .......................................................................................................................... 5 2. Impact on the humanitarian situation ................................................................................... 5 3. Regional and International Response .................................................................................. 6 4. Sub-regional Linkages.......................................................................................................... 7 5. Sub-regional Challenges......................................................................................................8 6. Rationale for a Sub-regional and Multi-disciplinary Approach ............................................ -

Guinea: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

REPUBLIC OF GUINEA Work – Justice – Solidarity Ministry of the Economy, Finances and Planning Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2 (2007–2010) Conakry, August 2007 Permanent Secretariat for the Poverty Reduction Strategy (SP-SRP) Website: www.srp-guinee.org.Telephone: (00224) 30 43 10 80. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document is the fruit of a collective effort that has involved many development stakeholders: executives of regionalized and decentralized structures, civil society organizations, development partners, etc. Warm thanks to all of them. The government would particularly like to acknowledge the grassroots organizations and civil society actors who, despite the difficulties that affected the implementation of the PRSP-I, have renewed their confidence in its action. The lessons learned from the implementation of the PRSP-I have helped in the design and preparation of the document. For this, the government again thanks the development partners who have accompanied it in this exercise and provided technical and financial contributions (EU, GTZ, SCAC, Canadian Cooperation), as well as the team of national experts who carried out field work with dedication and professionalism. Furthermore, without the painstaking work carried out in 2005 and 2006 as part of the process of refining the regional PRSPs, it certainly would not have been possible to prepare this document. The same is true of the work done, mainly in 2006, to evaluate needs aimed at reaching the MDGs. In this regard, we thank the United Nations System, and in particular the UNDP, for its exceptional contribution. Finally, the government extends its most sincere thanks to all those, both named and unnamed, who participated in this collective work. -

Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2

© 2008 International Monetary Fund January 2008 IMF Country Report No. 08/7 Guinea: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) are prepared by member countries in broad consultation with stakeholders and development partners, including the staffs of the World Bank and the IMF. Updated every three years with annual progress reports, they describe the country's macroeconomic, structural, and social policies in support of growth and poverty reduction, as well as associated external financing needs and major sources of financing. This country document for Guinea, dated August 2007, is being made available on the IMF website by agreement with the member country as a service to users of the IMF website. To assist the IMF in evaluating the publication policy, reader comments are invited and may be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. Copies of this report are available to the public from International Monetary Fund • Publication Services 700 19th Street, N.W. • Washington, D.C. 20431 Telephone: (202) 623-7430 • Telefax: (202) 623-7201 E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.imf.org Price: $18.00 a copy International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution This page intentionally left blank ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution REPUBLIC OF GUINEA Work – Justice – Solidarity Ministry of the Economy, Finances and Planning Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2 (2007–2010) Conakry, August 2007 Permanent Secretariat for the Poverty Reduction Strategy (SP-SRP) Website: www.srp-guinee.org.Telephone: (00224) 30 43 10 80. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document is the fruit of a collective effort that has involved many development stakeholders: executives of regionalized and decentralized structures, civil society organizations, development partners, etc. -

Evaluation of the Hydroenergetic Potential of the Fall from Kalako to Dabola, Guinea

International Journal of Advanced Research and Publications ISSN: 2456-9992 Evaluation Of The Hydroenergetic Potential Of The Fall From Kalako To Dabola, Guinea. Doussou Lancine TRAORE, Yacouba CAMARA, Ansoumane SAKOUVOGUI, Mamby KEITA Polytechnic Institute, Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry - Guinea, Energy Department, Higher Institute of Technology of Mamou - Guinea, Department of Physics, Faculty of Sciences, Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry - Guinea, Traoredl54 @ gmail.com, +224 628 991426 [email protected], +224 622288295 [email protected], +224 628016168 [email protected], +224 622681932 Abstract: The hydro-energetic potential of the Kalako site on the Tinkisso River in Dabola prefecture, evaluated by the spot measurement method during the month of March (dry season) is 5085.50 kW, or about 5.1 MW. This value is in the range of mini hydroelectric plants. The values of the evaluation parameters of this hydroenergetic potential at this time are: the depth of the watercourse (0.58 m), the flow velocity (1.46 m/s), the flow rate (14.4 m3/s), the drop height (60 m) and the efficiency of the electromechanical equipment (60%). Such a regular assessment of the hydroelectric potential of all waterfalls available in the country would provide a reliable database on the existing hydroelectric potential, hence the objective of this research. Key words: Assessment, potential, hydropower, useful power. 1.Introduction these hydroelectric potentials is often based on analyzes of Hydroelectric power is a renewable energy obtained by meteorological and hydrological data over a long period (25 converting the hydraulic energy of the various natural water to 50 years). It turns out that for most of these sites in flows into electricity. -

Ecologically Sensitive Sites in Africa. Volume 1

Ecologically Sites in Africa Volume I: Occidental and Central Africa Benin Cameroon Central African Republic Congo Cdte d'lvoire Eq uatorlil^lllpvea aSon Guinea Complled'by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre For TK^^o^d Bdnk Ecologically Sensitive Sites in Africa Volume I: Occidental and Central Africa WORLD CONSERVATION! MONITORING CENTRE 2 4 MAY 1995 Compiled by PROTECTED AREAS | World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK for The World Bank Washington DC, USA The World Bank 1993 Published by The World Bank, Washington, DC, USA. Prepared by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL, UK. WCMC is a joint venture between the three partners who developed The World Conservation Strategy and its successor Caring for the Earth: lUCN-World Conservation Union, UNEP-United Nations Environment Programme, and WWF- World Wide Fund for Nature. Its mission is to provide an information, research and assessment service on the status, security and management of the Earth's biological diversity as the basis for its conservation and sustainable use. Copyright: 1993 The World Bank Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior permission from the copyright holder. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: World Bank (1993). Ecologically Sensitive Sites in Africa. Volume I: Occidental and Central Africa. Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre for The World Bank, Washington, DC, USA. Printed by: The Burlington Press, Cambridge, UK. Cover illustration: Nairobi City Skyline with Kongoni and Grant's Gazelles, RIM Campbell. -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions: Guinea

REVISION OF THE LIVELIHOODS ZONE MAP AND DESCRIPTIONS FOR THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA A REPORT OF THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWROK (FEWS NET) November 2016 This report is based on the original livelihoods zoning report of 2013 and was produced by Julius Holt, Food Economy Group, consultant to FEWS NET GUINEA Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions November 2016 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Changes to the Livelihood Zones Map ...................................................................................................................... 5 The National Context ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Livelihood Zone Descriptions .................................................................................................................................. 10 ZONE GN01 LITTORAL: RICE, FISHING, PALM OIL ................................................................................................................................................. -

Lacey Andrews WP 88

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Working Paper No. 88 When is a refugee not a refugee? Flexible social categories and host/refugee relations in Guinea B. Lacey Andrews Brown University Providence, Rhode Island, USA E-mail : [email protected] March 2003 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees CP 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These working papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction UNHCR and humanitarian agencies commonly use the category of “refugee” in order to determine the population eligible for aid or resettlement. However, for understanding the dynamics of long-term conflict and how the displaced themselves negotiate their survival with their hosts, this demographic category obscures more than it reveals. This paper focuses on relations between the residents of the Sembakounya camp, Kola camp, and the neighboring Guinean villages and towns during the first months of these Guinean camps’ existence, as initial fears and stereotypes were being formed and negotiated.1 Tania Kaiser raised the issue of refugee/host relationships in her 2000 report entitled “A beneficiary-based evaluation of UNHCR’s programme in Guinea, West Africa”. While the major concerns at that time in the pre-crisis Gueckadou region were land scarcity, food shortages, lack of identification papers, and the low-level of funding for UNHCR’s programs, in a prescient statement, she drew attention to the needs of the surrounding communities: “Given the length of time that UNHCR has been operating around Gueckadou, little attention has been paid to the host population in this refugee affected area. -

Page 1 S.NO Sub-Prefecture Non 00 10 17 18 Alassoya Albadaria

S.No Sub-prefecture 1 Alassoya 2 Albadaria 3 Arfamoussaya 4 Babila 5 Badi 6 Baguinet 7 Balaki 8 Balandougou 9 Balandougouba, Kankan 10 Balandougouba, Siguiri 11 Balato 12 Balaya 13 Balizia 14 Banama 15 Banankoro 16 Banfélé 17 Bangouyah 18 Banguingny 19 Banian 20 Banié 21 Banko 22 Bankon 23 Banora 24 Bantignel 25 Bardou 26 Baro 27 Bate-Nafadji 28 Beindou, Faranah 29 Beindou, Kissidougou 30 Benty 31 Beyla-Centre 32 Bheeta 33 Bignamou 34 Binikala 35 Bintimodiya 36 Bissikrima 37 Bodié 38 Boffa-Centre 39 Bofossou 40 Boké-Centre 41 Bolodou 42 Boola 43 Bossou 44 Boula 45 Bouliwel 46 Bounouma www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Bourouwal 48 Bourouwal-Tappé 49 Bowé 50 Cisséla 51 Colia 52 Coyah-Centre 53 Dabiss 54 Dabola-Centre 55 Dalaba-Centre 56 Dalein 57 Damankanyah 58 Damaro 59 Daralabe 60 Daramagnaky 61 Daro 62 Dialakoro, Faranah 63 Dialakoro, Kankan 64 Diara-Guerela 65 Diari 66 Diassodou 67 Diatiféré 68 Diécké 69 Dinguiraye-Centre 70 Dionfo 71 Diountou 72 Ditinn 73 Dixinn 74 Dogomet 75 Doko 76 Donghol-Sigon 77 Dongol-Touma 78 Douako 79 Dougountouny 80 Dounet 81 Douprou 82 Doura 83 Dubréka-Centre 84 Fafaya 85 Falessade 86 Fangamadou 87 Faralako 88 Faranah-Centre 89 Farmoriah 90 Fassankoni 91 Fatako 92 Fello-Koundoua 93 Fermessadou-Pombo www.downloadexcelfiles.com 94 Firawa 95 Forécariah-Centre 96 Fouala 97 Fougou 98 Foulamory 99 Foumbadou 100 Franwalia 101 Fria-Centre 102 Friguiagbé 103 Gadha-Woundou 104 Gagnakali 105 Gama 106 Gaoual-Centre 107 Garambé 108 Gayah 109 Gbakedou 110 Gbangbadou 111 Gbessoba 112 Gbérédou-Baranama 113 Gnaléah 114 Gongore -

GEOLEV2 Label Updated October 2020

Updated October 2020 GEOLEV2 Label 32002001 City of Buenos Aires [Department: Argentina] 32006001 La Plata [Department: Argentina] 32006002 General Pueyrredón [Department: Argentina] 32006003 Pilar [Department: Argentina] 32006004 Bahía Blanca [Department: Argentina] 32006005 Escobar [Department: Argentina] 32006006 San Nicolás [Department: Argentina] 32006007 Tandil [Department: Argentina] 32006008 Zárate [Department: Argentina] 32006009 Olavarría [Department: Argentina] 32006010 Pergamino [Department: Argentina] 32006011 Luján [Department: Argentina] 32006012 Campana [Department: Argentina] 32006013 Necochea [Department: Argentina] 32006014 Junín [Department: Argentina] 32006015 Berisso [Department: Argentina] 32006016 General Rodríguez [Department: Argentina] 32006017 Presidente Perón, San Vicente [Department: Argentina] 32006018 General Lavalle, La Costa [Department: Argentina] 32006019 Azul [Department: Argentina] 32006020 Chivilcoy [Department: Argentina] 32006021 Mercedes [Department: Argentina] 32006022 Balcarce, Lobería [Department: Argentina] 32006023 Coronel de Marine L. Rosales [Department: Argentina] 32006024 General Viamonte, Lincoln [Department: Argentina] 32006025 Chascomus, Magdalena, Punta Indio [Department: Argentina] 32006026 Alberti, Roque Pérez, 25 de Mayo [Department: Argentina] 32006027 San Pedro [Department: Argentina] 32006028 Tres Arroyos [Department: Argentina] 32006029 Ensenada [Department: Argentina] 32006030 Bolívar, General Alvear, Tapalqué [Department: Argentina] 32006031 Cañuelas [Department: Argentina] -

12086674.Pdf

EN MOYENNE ET HAUTE GUINEE DURABLE LE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL POUR L’ETUDE ET LA PLANIFICATION Bureau de Stratégie et Développement Ministère de l’Agriculture République de Guinée EN REPUBLIQUE DE GUINEE EN REPUBLIQUE L’ETUDE ET LA PLANIFICATION POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL DURABLE EN MOYENNE ET HAUTE GUINEE Rapport final (Annexes) RAPPORT FINAL (Annexes) Janvier 2013 Janvier 2013 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale NTC International Co., Ltd RD JR 13-008 Bureau de Stratégie et Développement Ministère de l’Agriculture République de Guinée L’ETUDE ET LA PLANIFICATION POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL DURABLE EN MOYENNE ET HAUTE GUINEE Rapport final Annexe Janvier 2013 NTC International Co., Ltd L’Etude et la planification pour le développement rural durable en Moyenne et Haute Guinée GUINÉE SÉNÉGAL MALI GUINÉE‐BISSAU KOUNDÂRA LABÉ MOYENNE GUINÉE MALI BOKÉ GAOUAL KOUBIA SIGUIRI LÉLOUMA DINGUIRAYE TOUGUÉ LABÉ HAUTE GUINÉE KANKAN PITA DALABA GUINÉE MARITIME DABOLA KOUROUSSA MANDIANA MAMOU MAMOU KANKAN FARANAH KINDIA Conakry FARANAH (Capital) KEROUANÉ SIERRA LEONE NZÉRÉKORÉ 〈Légende 〉 GUINÉEFORESTIÉRE Frontière de la région Capital MOYENNE GUINÉE HAUTE GUINÉE LIBÉRIA CÔTE texte:Nom de préfecture qui est inclus D'IVOIRE dans la zone d'étude エラー! Guinée Plan d’emplacement des zones faisant l’objet de la présente étude Liste des abréviations ACA l'Agence pour la Commercialisation Agricole ACM Associations de Cautionnement Mutuel ANPROCA Agence National de Promotion Rural et Conseille Agricole A/P Activité Pilote ASF Association Service Financière