Guinea: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II

OFFICIAL USE ONLY IDA/SecM2007-0684 December 12, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized For meeting of Board: Tuesday, January 8, 2008 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Guinea: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note 1. Attached is the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II. The IMF is currently scheduled to discuss this document on December 21, 2007. 2. The PRSP II was prepared by the Government of Guinea. The paper acknowledges the disappointing outcome of the first PRSP, which covered the period 2002-2006. The political, social and economic environment in which the implementation of PRSP I took place was characterized by poor governance, political instability, and low growth which led to an increase in poverty from 49 percent in 2002 to an estimated 54 percent in 2005. Overall, public service delivery deteriorated in terms of both quality and access and the living conditions for most Guineans worsened. Public Disclosure Authorized 3. PRSP II aims at recapturing lost ground over the past five years. The overall strategy is based on three pillars: (i) improving governance; (ii) accelerating growth and increasing employment opportunities; and (iii) improving access to basic services. It focuses on restoring macroeconomic stability, institutional and structural reforms, and mechanisms to strengthen the democratic process implementation capacity. 4. As approved by the Board on August 6, 2007, the pilot Board Technical Questions and Answer Database (http://boardqa.worldbank.org or from the EDs' portal) is now open for questions. -

Recipient UN Organization(S): UNICEF UNDP Proposal Contacts

EBOLA RESPONSE MULTI-PARTNER TRUST FUND PROPOSAL Proposal Title: Stop Ebola through social Recipient UN Organization(s): mobilization and community engagement in Guinea UNICEF UNDP Proposal Contacts: Implementing Partner(s) – name & type For UNICEF (Government, CSO, etc.): Dr Mohamed Ayoya - NGOs: Plan Guinée, CERAD, Resident Representative CENAFOD, CNOSCG; youth Address: UNICEF, Corniche, Coleah, Conakry organizations Telephone: +224 622 663 452 - Government. E-mail: [email protected] For UNDP Aissatou Cisse-Yao Yao Deputy Country Director, Programme Address:UNDP Guinée Maison Commune Coléah Commune de Matam BP : 222 Conakry République de Guinée Telephone: 224 622 35 54 69 E-mail: [email protected] Proposal Location (country): Proposal Location (provinces): Please select one from the following Conakry, Boke, Kindia, Mamou, Faranah, Guinea Kankan, Nzerekore. Liberia (see map in Annex for detailed targets locations) Sierra Leone Common Services Project Description: Requested amount: One sentence describing the project’s scope and focus. USD 3,139,364 UNICEF USD 809,000 UNDP Through social mobilization, with a particular focus on Total requested amount: USD 3,948,364 vulnerable and at-risk groups such as women and youth, UNICEF and UNDP will support communities Other sources of funding of this proposal: to setup Community Watch Committees (CWCs), UNICEF regular resources door-to-door sensitization and referral of Ebola UNDP core fund suspected and contact cases. UNMEER budget: Other sources (indicate): Government Input: in kind support 1 Start Date: 10 December 2014 End Date: 15 June 2015 Total duration (in months): 6 months MISSION CRITICAL ACTIONS to which the proposal is contributing. For reporting purposes, each project should contribute to one SO. -

Appraisal Report Kankan-Kouremale-Bamako Road Multinational Guinea-Mali

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ZZZ/PTTR/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT KANKAN-KOUREMALE-BAMAKO ROAD MULTINATIONAL GUINEA-MALI COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION JANUARY 1999 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROJECT INFORMATION BRIEF, EQUIVALENTS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES AND TABLES, BASIC DATA, PROJECT LOGICAL FRAMEWORK, ANALYTICAL SUMMARY i-ix 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Genesis and Background.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Performance of Similar Projects..................................................................................... 2 2 THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Transport Sector in the Two Countries ................................................................... 3 2.2 Transport Policy, Planning and Coordination ................................................................ 4 2.3 Transport Sector Constraints.......................................................................................... 4 3 THE ROAD SUB-SECTOR .............................................................................................. 5 3.1 The Road Network ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Automobile Fleet and Traffic................................................................................. -

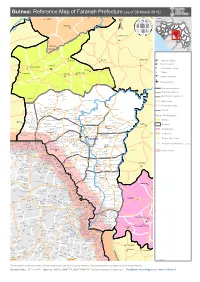

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (As of 05 March 2015)

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (as of 05 March 2015) Kalinko SENEGAL MALI GUINEA Sélouma BISSAU GUINEA Komola Koura COTE D'IVOIRE SIERRA LEONE Dialakoro Kankama LIBERIA Sisséla Sanguiana Bissikirima Regional Capital District Capital Dabola Arfamoussayah Sub District Capital Banko Kounendou Village Dogomet N'demba Unpaved runway Paved runway Region boundaries Koulambo District boundaries Morigbeya Dar Es Salam Daro Gada Walan Sub District boundaries Kindoyé DIGUILA CENTRE Fabouya TOUMANIA CENTRE Boubouya Main roads Yombo Nialen Moria Dansoya Secondary roads NIENOUYA CENTRE Teliayaga Doukou Passaya Souriya Mansira Moribaya KONDEBOU KASSA BOUNA CENTRE Tambaya Rivers Foya Gadha Mongoli Babakadia Hafia Gomboya BELEYA CENTRE SABERE KALIA Keema SOUNGBANYA CENTRE Balandou Beindougou SANSANKO CENTRE Sidakoro Gueagbely Gueafari Sokora District (Préfectures) Harounaya Miniandala Badhi Gnentin Oussouya Banire Wolofouga Lamiya Gueagbely Mameyire SANSAMBOU CENTRE BIRISSA CENTRE NGUENEYA CENTRE NIAKO CENTRE Koumandi Koura Dabola Wassakaria Kobalen Bingal Dansoya Tomata Konkofaya Heredou Marela karimbou Sansamba Bouran SOLOYA CENTRE Kolmatamba KOUMANDI KORO Sanamoussaya MILIDALA CENTRE Banfele Labatara Gninantamba BONTALA Koura Sambouya DIANA CENTRE Sansando Faranah Wossekalia FRIGUIA CENTRE MAGNA Halossagoya KALIA CENTRE I KOMBONYA Ballayany Herewa Alia Filly Fore Sakoromaya SOLONYEREYA Khamaya Bindou Dansaya Koutamodiya Salia Kamako Kissidougou Goulouya Fantoumaniya Nerekoro SEREKORO CENTRE Guidonya Kombonyady Wassambala Balankhamba Kabaya -

Guinea : Reference Map of Kankan Region (As of 3 March 2015)

Guinea : Reference Map of Kankan Region (as of 3 March 2015) Bankolen Mambifagalena Niagassola Kry Tourelen Berlen Sokoromansa Magadiano Faraboloni Linkekoro KIGNEKOUROU CENTRE Bouyido Malsadou Seourou Konfara 2 Gnembou Tanssa Magnaka KOTE CENTRE Balenda SOUMBARAYA CENTRE Kourelen TALABE CENTRE Dialawassa II Kondoko Djanwely Itipony Dougounta Dora Kourakoda DIBIA CENTRE Djinko Ilimalo Naboun Kanimbakalako Kodougoulen KAKAMA CENTRE Tondo Komagron Kayaga Kignedi Sininko Kadabili Kignero Gnere Sininkoro Badamako Kounsounkoro Yirikelèma Kanikoumbaya SOKORO CENTRE DIATEA CENTRE Dita Salla Tondji1 Koda Kebesabaya Siguirini Sakounou Malea Bembéta Megnèkoma Silabado Diakan Toukönö BOULAN CENTRE Gbèdela MANKADIAN CENTRE Gbörökola Doko Tombani Maragbè Kana Sékela Mansadji Sidao Tonso Banankölö Tomba Doula Amina Amina Kinièba Franwalia Tinko Diatifere Fountou Soumbalakölen Iroda Kounkoun Koda Mainou SARAYA CENTRE Tomboni Sinimbaya KOBEDRA CENTRE MIGNADA CENTRE Bökökö Farani Banora Simbona Bida Tomba Boufe Bandioula FOULATA CENTRE Kintinian Yorola Tougnou Sanouna SEELA CENTRE Bankon MALI Tinkoba Kobada Beretela Sando Noumandiana Kandani Fodela Bèrèko Tabakoro BAMBALA Tabako Madila Moyafara Kourouni Banantamou Siguiri FALAMA BANFARA CENTRE Saint Alexis Dialakoro Nedekoroko Banantou Lansanaya Sakolado Manakoro Farabada Dounin Farabelen Bida Bantambaye Woléwoléya Koda Koda Kogne Tambabougou Gbongoroma Kigne Kokoudouninda Dinguiraye Gbilin Balandougouba KONKOYE CENTRE Waran-Fougou Kiniebakoura DIARRADOU CENTRE Sansani Faradjian Tassiliman Centre Kewoulé -

Guinea-Bissau Mali !

G U I N E A - K I N D I A R E G I O N f h Logistics and Health Facilities Overview as of 13 February 2015 Popodara Tountouroun KOUBIA Parawol Diari LABE Dionfo Deliganjan Kakony Labe Kaalan LABE LELOUMA LABE Noussy GAOUAL Hafia Daralabe Timbi BOKE Madina Sangaredi Wuansa Pita Yaari Diaga, Bodie N TELIMELE N " Sogorayah Misside " 0 0 ' Touma ' 0 0 ° ° 1 1 1 Donghol 1 Ley Miro Bomboli MAMOU Goundoupi Maci Fonfoya DALABA Telimele Pellel PITA Ditinn Ditinn Mitty Beli Kouravei Kaala Poungoulel Kotouhi Bantanghi Mamassigui Gokima Bovi Schindi Boundoukoura Dounkimagna DianatoroGouba Petti-Doa Dalabakala Kobin Diarekal Kampa Fellopouri Tangama Dounguibiri Dalaba Badahia Dikourou Koba Bohouda BOKE N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 0 0 1 FRIA 1 BOFFA MAMOU Fria Mamou Horevelo FRIA Kunekure Tamagali Linsan KINDIA Sougeta KINDIA DUBREKA Koulente Koluhare Koubia Siguiton Maleya Wassou Kindia N N " " 0 0 ' Damakania ' 0 0 ° Segueya ° 0 0 1 Koab 1 Saboya Toureya Sabouia Friguibe Koliagbe Camara-Bouyni Gbnkli Mambya Dubreka Kouryia Balahn Wonkifong COYAH Coyah Gomokouri Coyah CONAKRY Sikhourou CONAKRY Sekourou Conakry CONAKRY Louis Pasteur / National Reference Lab Conakry Donka Hospital N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 9 9 Moussayah Laya Forecariah FORECARIAH Farmoreyah Farmoreah SIERRA SENEGAL Pamalap LEONE Bamako !. Benti Benty GUINEA-BISSAU MALI !. LABE BOKE N MAMOU KANKAN N " " 0 0 ' FARANAH ' 0 0 ° ° 9 ± KINDIA 9 0 12.5 25 50 Kilometers CO!.NAKRY Ebola Treatment Unit, Conakry b WFP Country Office National Capital International Airport Highway International boundary GF Open .! (!o o Ebola Treatment Unit, WFP Sub Office Major Town Airstrip Primary Road Region boundary Makeni GF Under Construction k (! Community Care ! Main Logistics Hub !( Intermediate Town h Port Secondary Road Prefecture boundary Centre, Planned ! SIERRA LEONE CÔTE D'IVOIRE Freetown !. -

Download Map (PDF | 1.37

GUINEE: Couverture des bureaux de zones ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sambailo ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! SENEGAL ! ! ! ! ! Koundara Ctre ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Youkounkoun ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sareboido ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Termesse ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Koundara ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Kamabi ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Guinguan ! ! ! ! Balaki ! ! !! ! ! ! ! Lebekeren ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Touba ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Foulamory ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Niagassola ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mali Mali Ctre ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Naboun ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Madina Wora ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Gadha Woundou ! Hidayatou ! ! GUINEE BISSAU ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Gayah ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Salambande ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Labe ! ! ! ! Fougou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Telire ! ! Kounsitel ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Dougountouny ! ! Fello Koundoua ! Siguirini ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Gagnakaly ! ! ! ! ! ! MALI ! ! ! ! ! ! Franwalia ! Fafaya ! ! ! ! Linsan Saran Yimbering Donghol Sigon Diatifere ! ! ! Banora ! Matakaou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Gaoual Ctre ! ! ! ! Koumbia ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Doko ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

Sierra Leone – Prospects for Peace Severely Compromised

CONSOLIDATED INTER-AGENCY APPEALS FOR 2001 UNITED NATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL COPIES, PLEASE CONTACT: UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS PALAIS DES NATIONS 8-14 AVENUE DE LA PAIX CH - 1211 GENEVA, SWITZERLAND TEL.: (41 22) 917.1972 FAX: (41 22) 917.0368 E-MAIL: [email protected] THIS DOCUMENT CAN ALSO BE FOUND ON http://www.reliefweb.int/ TABLE OF CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 TABLE I :TOTAL FUNDING REQUIREMENTS - BY AGENCY AND COUNTRY ........................................3 TABLE II: SUMMARY OF REQUIREMENTS BY SECTOR AND APPEALING AGENCY............................4 SUB-REGIONAL OVERVIEW......................................................................................................... 5 1. Background .......................................................................................................................... 5 2. Impact on the humanitarian situation ................................................................................... 5 3. Regional and International Response .................................................................................. 6 4. Sub-regional Linkages.......................................................................................................... 7 5. Sub-regional Challenges......................................................................................................8 6. Rationale for a Sub-regional and Multi-disciplinary Approach ............................................ -

MCHIP Guinea End-Of-Project Report October 2010–June 2014

MCHIP Guinea End-of-Project Report October 2010–June 2014 Submitted on: September 15, 2014 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development under Coooperative Agreement # GHS-A-00-08-00002-000 Submitted by: Yolande Hyjazi, Rachel Waxman and Bethany Arnold 1 The Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) is the USAID Bureau for Global Health’s flagship maternal, neonatal and child health (MNCH) program. MCHIP supports programming in maternal, newborn and child health, immunization, family planning, malaria, nutrition, and HIV/AIDS, and strongly encourages opportunities for integration. Cross-cutting technical areas include water, sanitation, hygiene, urban health and health systems strengthening. MCHIP brings together a partnership of organizations with demonstrated success in reducing maternal, newborn and child mortality rates and malnutrition. Each partner will take the lead in developing programs around specific technical areas: Jhpiego, as the Prime, will lead maternal health, family planning/reproductive health, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT); JSI—child health, immunization, and pediatric AIDS; Save the Children—newborn health, community interventions for MNCH, and community mobilization; PATH—nutrition and health technology; JHU/IIP—research and evaluation; Broad Branch—health financing; PSI—social marketing; and ICF International—continues support for the Child Survival and Health Grants Program (CSHGP) and the Malaria Communities Program (MCP). This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of the Leader with Associates Cooperative Agreement GHS-A-00-08-00002-00. The contents are the responsibility of the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. -

Impact of the Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak on Market Chains And

FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Dakar, 2016 The conclusions given in this information product are considered appropriate at the time of its preparation. They may be mod- ified in the light of further knowledge gained at subsequent stages of the project. In particular, the recommendations included in this information product were valid at the time they were written, during the FAO workshop on the market chains and trade of agricultural products in the context of the Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa, organized in December 2014 in Dakar, Senegal. The views expressed in this information product are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not men- tioned. ISBN 978-92-5-109223-1 © FAO, 2016 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise in- dicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. -

Guinea - Number of Confirmed Ebola Cases and Population by Sous - Préfecture (As of 11 April 2015)

Guinea - Number of confirmed Ebola cases and population by Sous - préfecture (as of 11 April 2015) Sambailo SENEGAL Youkounkoun Sareboido Termesse Kamabi Lebekeren Balaki Touba Foulamory Guinguan Mali Niagassola Naboun Ctre Madina Gadha MALI GUINEA-BISSAU Wora Gayah Hidayatou Salambande Woundou Gagnakaly Fougou Kounsitel Telire Fello Koundoua Linsan Donghol Siguirini Matakaou Fafaya Diatifere Franwalia Saran Yimbering Sigon Koumbia Banora Malea Doko Kouratongo Koubia Tianguel Ctre Malanta Bori Lafou Pilimini Wendou Diontou Bankon Korbe Dalein Kintinian Mbour Kolet Siguiri Sansale Konah Balaya Sannou Tougue Dinguiraye Ctre Kakony Parawol Diari Lansanaya Dialokoro Dabiss Kaalan Dionfo Tangali Sagale Ctre Ctr Balandougouba Kiniebakoura Noussy Koin Kalinko Koba Timbi Hafia Mombeyah Fatako Herico Madina Kansangui Komola Koundianakoro Missira Norassoba Niandankoro Bantignel Kankalabe Selouma Khoura Sangaredi Santou Ninguelande Bourouwal Kolangui Teguereyah Sansando Kinieran Timbi Bodie Donghol Brouwal Dialakoro Tarihoye Touni Kebali Boke Ley Touma Tape Mafara Bissikrima Kanfarande Konsotami Morodou Niantanina Ctre Telemele Miro Maci Ditinn Kankama Cissela Ctre Mitty Nyagara Doura Koundian Kolaboui Kaala Bate Daramagnaky Thionthian Dabola Koumana Malapouya Gongoret Ctre Nafadji Dalaba Saramoussaya Sanguiana Balato Kamsar Sinta Ctre Banguigny Sangareah Faralako Poredaka Dogomet Ndema Banko Babila Mandiana Bintimodia Sogolon Timbo Kouroussa Baro Karifamoriah Ctre Kolia Konendou Ctre Balandougou Baguinet Tolo Dounet Kindoye Mankountan Lisso Fria -

Elements De La Carte Sanitaire Des Etablissements De Soins Du Secteur Public

REPUBLIQUE DE GUINEE ----------------- Travail - Justice - Solidarité MINISTERE DE LA SANTE PUBLIQUE ELEMENTS DE LA CARTE SANITAIRE DES ETABLISSEMENTS DE SOINS DU SECTEUR PUBLIC JANVIER 2012 TABLE DES MATIERES CHAPITRE I : SITUATION ACTUELLE DES ETABL ISSEMENTS DE SOINS ............................................. 4 I - TYPOLOGIE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 II - NIVEAU PRIMAIRE ............................................................................................................................................ 4 III - NIVEAU SECONDAIRE ..................................................................................................................................... 7 IV - NIVEAU TERTIAIRE ........................................................................................................................................ 10 V - POINTS FAIBLES .............................................................................................................................................. 12 VI - POINTS FORTS ................................................................................................................................................ 13 VII - CONTRAINTES ............................................................................................................................................... 13 VIII - OPPORTUNITES ET MENACES ..................................................................................................................