Guineavolumeicover Version2 05.04.06.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II

OFFICIAL USE ONLY IDA/SecM2007-0684 December 12, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized For meeting of Board: Tuesday, January 8, 2008 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Guinea: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note 1. Attached is the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II. The IMF is currently scheduled to discuss this document on December 21, 2007. 2. The PRSP II was prepared by the Government of Guinea. The paper acknowledges the disappointing outcome of the first PRSP, which covered the period 2002-2006. The political, social and economic environment in which the implementation of PRSP I took place was characterized by poor governance, political instability, and low growth which led to an increase in poverty from 49 percent in 2002 to an estimated 54 percent in 2005. Overall, public service delivery deteriorated in terms of both quality and access and the living conditions for most Guineans worsened. Public Disclosure Authorized 3. PRSP II aims at recapturing lost ground over the past five years. The overall strategy is based on three pillars: (i) improving governance; (ii) accelerating growth and increasing employment opportunities; and (iii) improving access to basic services. It focuses on restoring macroeconomic stability, institutional and structural reforms, and mechanisms to strengthen the democratic process implementation capacity. 4. As approved by the Board on August 6, 2007, the pilot Board Technical Questions and Answer Database (http://boardqa.worldbank.org or from the EDs' portal) is now open for questions. -

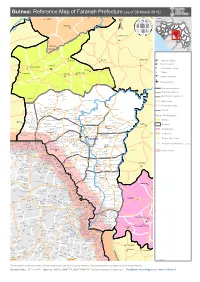

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (As of 05 March 2015)

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (as of 05 March 2015) Kalinko SENEGAL MALI GUINEA Sélouma BISSAU GUINEA Komola Koura COTE D'IVOIRE SIERRA LEONE Dialakoro Kankama LIBERIA Sisséla Sanguiana Bissikirima Regional Capital District Capital Dabola Arfamoussayah Sub District Capital Banko Kounendou Village Dogomet N'demba Unpaved runway Paved runway Region boundaries Koulambo District boundaries Morigbeya Dar Es Salam Daro Gada Walan Sub District boundaries Kindoyé DIGUILA CENTRE Fabouya TOUMANIA CENTRE Boubouya Main roads Yombo Nialen Moria Dansoya Secondary roads NIENOUYA CENTRE Teliayaga Doukou Passaya Souriya Mansira Moribaya KONDEBOU KASSA BOUNA CENTRE Tambaya Rivers Foya Gadha Mongoli Babakadia Hafia Gomboya BELEYA CENTRE SABERE KALIA Keema SOUNGBANYA CENTRE Balandou Beindougou SANSANKO CENTRE Sidakoro Gueagbely Gueafari Sokora District (Préfectures) Harounaya Miniandala Badhi Gnentin Oussouya Banire Wolofouga Lamiya Gueagbely Mameyire SANSAMBOU CENTRE BIRISSA CENTRE NGUENEYA CENTRE NIAKO CENTRE Koumandi Koura Dabola Wassakaria Kobalen Bingal Dansoya Tomata Konkofaya Heredou Marela karimbou Sansamba Bouran SOLOYA CENTRE Kolmatamba KOUMANDI KORO Sanamoussaya MILIDALA CENTRE Banfele Labatara Gninantamba BONTALA Koura Sambouya DIANA CENTRE Sansando Faranah Wossekalia FRIGUIA CENTRE MAGNA Halossagoya KALIA CENTRE I KOMBONYA Ballayany Herewa Alia Filly Fore Sakoromaya SOLONYEREYA Khamaya Bindou Dansaya Koutamodiya Salia Kamako Kissidougou Goulouya Fantoumaniya Nerekoro SEREKORO CENTRE Guidonya Kombonyady Wassambala Balankhamba Kabaya -

Sierra Leone – Prospects for Peace Severely Compromised

CONSOLIDATED INTER-AGENCY APPEALS FOR 2001 UNITED NATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL COPIES, PLEASE CONTACT: UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS PALAIS DES NATIONS 8-14 AVENUE DE LA PAIX CH - 1211 GENEVA, SWITZERLAND TEL.: (41 22) 917.1972 FAX: (41 22) 917.0368 E-MAIL: [email protected] THIS DOCUMENT CAN ALSO BE FOUND ON http://www.reliefweb.int/ TABLE OF CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 TABLE I :TOTAL FUNDING REQUIREMENTS - BY AGENCY AND COUNTRY ........................................3 TABLE II: SUMMARY OF REQUIREMENTS BY SECTOR AND APPEALING AGENCY............................4 SUB-REGIONAL OVERVIEW......................................................................................................... 5 1. Background .......................................................................................................................... 5 2. Impact on the humanitarian situation ................................................................................... 5 3. Regional and International Response .................................................................................. 6 4. Sub-regional Linkages.......................................................................................................... 7 5. Sub-regional Challenges......................................................................................................8 6. Rationale for a Sub-regional and Multi-disciplinary Approach ............................................ -

MCHIP Guinea End-Of-Project Report October 2010–June 2014

MCHIP Guinea End-of-Project Report October 2010–June 2014 Submitted on: September 15, 2014 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development under Coooperative Agreement # GHS-A-00-08-00002-000 Submitted by: Yolande Hyjazi, Rachel Waxman and Bethany Arnold 1 The Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) is the USAID Bureau for Global Health’s flagship maternal, neonatal and child health (MNCH) program. MCHIP supports programming in maternal, newborn and child health, immunization, family planning, malaria, nutrition, and HIV/AIDS, and strongly encourages opportunities for integration. Cross-cutting technical areas include water, sanitation, hygiene, urban health and health systems strengthening. MCHIP brings together a partnership of organizations with demonstrated success in reducing maternal, newborn and child mortality rates and malnutrition. Each partner will take the lead in developing programs around specific technical areas: Jhpiego, as the Prime, will lead maternal health, family planning/reproductive health, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT); JSI—child health, immunization, and pediatric AIDS; Save the Children—newborn health, community interventions for MNCH, and community mobilization; PATH—nutrition and health technology; JHU/IIP—research and evaluation; Broad Branch—health financing; PSI—social marketing; and ICF International—continues support for the Child Survival and Health Grants Program (CSHGP) and the Malaria Communities Program (MCP). This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of the Leader with Associates Cooperative Agreement GHS-A-00-08-00002-00. The contents are the responsibility of the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. -

Epidemie Eboly V Letech 2014-2015 a Reakce ČR

Epidemie Eboly v letech 2014-2015 a reakce ČR DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE Studijní program: VEŘEJNÉ ZDRAVOTNICTVÍ Autor: Lenka Rudlofová Vedoucí práce: MUDr. Jozef Dlhý, Ph. D. České Budějovice 2017 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že svoji diplomovou práci s názvem Epidemie Eboly v letech 2014-2015 a reakce ČR jsem vypracovala samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své diplomové práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby diplomové práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé diplomové práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. V Českých Budějovicích dne ………………………………. Poděkování Děkuji především panu doktoru Jozefovi Dlhému, Ph. D., který mi poskytoval cenné rady, byl pečlivý a měl se mnou trpělivost. Dále děkuji všem osobám, které mi zodpověděly mé elektronické dotazy ohledně problematiky epidemie. Epidemie Eboly v letech 2014-2015 a reakce ČR Abstrakt Práce se zabývá epidemií Eboly v letech 2014-2015 a reakcí ČR. Hlavním cílem práce je vyhodnotit strategii ČR k zamezení importu Eboly. Práce využívá studia dokumentů, snahou je komplexní náhled na danou problematiku. Použitými dokumenty jsou především informace a zprávy mezinárodních i českých organizací, předpisy, odborné články, elektronické dotazy a mediální zprávy. -

Guinea: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

REPUBLIC OF GUINEA Work – Justice – Solidarity Ministry of the Economy, Finances and Planning Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2 (2007–2010) Conakry, August 2007 Permanent Secretariat for the Poverty Reduction Strategy (SP-SRP) Website: www.srp-guinee.org.Telephone: (00224) 30 43 10 80. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document is the fruit of a collective effort that has involved many development stakeholders: executives of regionalized and decentralized structures, civil society organizations, development partners, etc. Warm thanks to all of them. The government would particularly like to acknowledge the grassroots organizations and civil society actors who, despite the difficulties that affected the implementation of the PRSP-I, have renewed their confidence in its action. The lessons learned from the implementation of the PRSP-I have helped in the design and preparation of the document. For this, the government again thanks the development partners who have accompanied it in this exercise and provided technical and financial contributions (EU, GTZ, SCAC, Canadian Cooperation), as well as the team of national experts who carried out field work with dedication and professionalism. Furthermore, without the painstaking work carried out in 2005 and 2006 as part of the process of refining the regional PRSPs, it certainly would not have been possible to prepare this document. The same is true of the work done, mainly in 2006, to evaluate needs aimed at reaching the MDGs. In this regard, we thank the United Nations System, and in particular the UNDP, for its exceptional contribution. Finally, the government extends its most sincere thanks to all those, both named and unnamed, who participated in this collective work. -

Elements De La Carte Sanitaire Des Etablissements De Soins Du Secteur Public

REPUBLIQUE DE GUINEE ----------------- Travail - Justice - Solidarité MINISTERE DE LA SANTE PUBLIQUE ELEMENTS DE LA CARTE SANITAIRE DES ETABLISSEMENTS DE SOINS DU SECTEUR PUBLIC JANVIER 2012 TABLE DES MATIERES CHAPITRE I : SITUATION ACTUELLE DES ETABL ISSEMENTS DE SOINS ............................................. 4 I - TYPOLOGIE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 II - NIVEAU PRIMAIRE ............................................................................................................................................ 4 III - NIVEAU SECONDAIRE ..................................................................................................................................... 7 IV - NIVEAU TERTIAIRE ........................................................................................................................................ 10 V - POINTS FAIBLES .............................................................................................................................................. 12 VI - POINTS FORTS ................................................................................................................................................ 13 VII - CONTRAINTES ............................................................................................................................................... 13 VIII - OPPORTUNITES ET MENACES .................................................................................................................. -

Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2

© 2008 International Monetary Fund January 2008 IMF Country Report No. 08/7 Guinea: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) are prepared by member countries in broad consultation with stakeholders and development partners, including the staffs of the World Bank and the IMF. Updated every three years with annual progress reports, they describe the country's macroeconomic, structural, and social policies in support of growth and poverty reduction, as well as associated external financing needs and major sources of financing. This country document for Guinea, dated August 2007, is being made available on the IMF website by agreement with the member country as a service to users of the IMF website. To assist the IMF in evaluating the publication policy, reader comments are invited and may be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. Copies of this report are available to the public from International Monetary Fund • Publication Services 700 19th Street, N.W. • Washington, D.C. 20431 Telephone: (202) 623-7430 • Telefax: (202) 623-7201 E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.imf.org Price: $18.00 a copy International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution This page intentionally left blank ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution REPUBLIC OF GUINEA Work – Justice – Solidarity Ministry of the Economy, Finances and Planning Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2 (2007–2010) Conakry, August 2007 Permanent Secretariat for the Poverty Reduction Strategy (SP-SRP) Website: www.srp-guinee.org.Telephone: (00224) 30 43 10 80. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document is the fruit of a collective effort that has involved many development stakeholders: executives of regionalized and decentralized structures, civil society organizations, development partners, etc. -

Evaluation of the Hydroenergetic Potential of the Fall from Kalako to Dabola, Guinea

International Journal of Advanced Research and Publications ISSN: 2456-9992 Evaluation Of The Hydroenergetic Potential Of The Fall From Kalako To Dabola, Guinea. Doussou Lancine TRAORE, Yacouba CAMARA, Ansoumane SAKOUVOGUI, Mamby KEITA Polytechnic Institute, Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry - Guinea, Energy Department, Higher Institute of Technology of Mamou - Guinea, Department of Physics, Faculty of Sciences, Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry - Guinea, Traoredl54 @ gmail.com, +224 628 991426 [email protected], +224 622288295 [email protected], +224 628016168 [email protected], +224 622681932 Abstract: The hydro-energetic potential of the Kalako site on the Tinkisso River in Dabola prefecture, evaluated by the spot measurement method during the month of March (dry season) is 5085.50 kW, or about 5.1 MW. This value is in the range of mini hydroelectric plants. The values of the evaluation parameters of this hydroenergetic potential at this time are: the depth of the watercourse (0.58 m), the flow velocity (1.46 m/s), the flow rate (14.4 m3/s), the drop height (60 m) and the efficiency of the electromechanical equipment (60%). Such a regular assessment of the hydroelectric potential of all waterfalls available in the country would provide a reliable database on the existing hydroelectric potential, hence the objective of this research. Key words: Assessment, potential, hydropower, useful power. 1.Introduction these hydroelectric potentials is often based on analyzes of Hydroelectric power is a renewable energy obtained by meteorological and hydrological data over a long period (25 converting the hydraulic energy of the various natural water to 50 years). It turns out that for most of these sites in flows into electricity. -

Ecologically Sensitive Sites in Africa. Volume 1

Ecologically Sites in Africa Volume I: Occidental and Central Africa Benin Cameroon Central African Republic Congo Cdte d'lvoire Eq uatorlil^lllpvea aSon Guinea Complled'by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre For TK^^o^d Bdnk Ecologically Sensitive Sites in Africa Volume I: Occidental and Central Africa WORLD CONSERVATION! MONITORING CENTRE 2 4 MAY 1995 Compiled by PROTECTED AREAS | World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK for The World Bank Washington DC, USA The World Bank 1993 Published by The World Bank, Washington, DC, USA. Prepared by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL, UK. WCMC is a joint venture between the three partners who developed The World Conservation Strategy and its successor Caring for the Earth: lUCN-World Conservation Union, UNEP-United Nations Environment Programme, and WWF- World Wide Fund for Nature. Its mission is to provide an information, research and assessment service on the status, security and management of the Earth's biological diversity as the basis for its conservation and sustainable use. Copyright: 1993 The World Bank Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior permission from the copyright holder. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: World Bank (1993). Ecologically Sensitive Sites in Africa. Volume I: Occidental and Central Africa. Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre for The World Bank, Washington, DC, USA. Printed by: The Burlington Press, Cambridge, UK. Cover illustration: Nairobi City Skyline with Kongoni and Grant's Gazelles, RIM Campbell. -

PRISM II MSH POUR RENFORCER LES Imerventions EN SANTE "--./ Rel'roouctive ET MST/SIDA

~ PRISM II MSH POUR RENFORCER LES ImERVENTIONS EN SANTE "--./ REl'ROOUCTIVE ET MST/SIDA . PRISM II Family Planning and Health Activity in Guinea QUARTERLY PROGRESS REpORT January - March 2003 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 2 SUMMARY OF PRINCIPALS RESUL TS ........................................................................ 3 WORK TOWARD THE INTERMEDIATE RESULTS (IR) ........................................... 4 IR1: INCREASED ACCESS ..................................... '" ...................................•.............. 4 IR 2: IMPROVED QUAlITY... ... ... ...... ....... ........ ... ..... ....... ......... .......... ....... ... ....... ........ II IR3: INCREASED DEMAND.. ... ... ...... ......... ...... ........... ...... .... ..... .... ................. ....... ..... 15 IR4: IMPROVED COORDINATION ............................................................................... 18 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION ............................................................................................... 21 NEXT QUARTER MAIN ACTIVITIES ....................................................................................... 23 List of acronyms Annexes: I. Projet d'Evaluation de l' Acceptabilite d'un Programme de Prevention du SIDA par une Intervention au Niveau de Ia Transmission Mere-Enfant du V1H en Haute Guinee; Compte-rendu de Kankan, Fevrier 2003, Dr. Tin-Nahn Luong (Sida3). 2. Trip Report: DMCI Strategy planuing workshop, -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions: Guinea

REVISION OF THE LIVELIHOODS ZONE MAP AND DESCRIPTIONS FOR THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA A REPORT OF THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWROK (FEWS NET) November 2016 This report is based on the original livelihoods zoning report of 2013 and was produced by Julius Holt, Food Economy Group, consultant to FEWS NET GUINEA Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions November 2016 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Changes to the Livelihood Zones Map ...................................................................................................................... 5 The National Context ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Livelihood Zone Descriptions .................................................................................................................................. 10 ZONE GN01 LITTORAL: RICE, FISHING, PALM OIL .................................................................................................................................................