Guinea Malaria Operational Plan FY 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II

OFFICIAL USE ONLY IDA/SecM2007-0684 December 12, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized For meeting of Board: Tuesday, January 8, 2008 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Guinea: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note 1. Attached is the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II. The IMF is currently scheduled to discuss this document on December 21, 2007. 2. The PRSP II was prepared by the Government of Guinea. The paper acknowledges the disappointing outcome of the first PRSP, which covered the period 2002-2006. The political, social and economic environment in which the implementation of PRSP I took place was characterized by poor governance, political instability, and low growth which led to an increase in poverty from 49 percent in 2002 to an estimated 54 percent in 2005. Overall, public service delivery deteriorated in terms of both quality and access and the living conditions for most Guineans worsened. Public Disclosure Authorized 3. PRSP II aims at recapturing lost ground over the past five years. The overall strategy is based on three pillars: (i) improving governance; (ii) accelerating growth and increasing employment opportunities; and (iii) improving access to basic services. It focuses on restoring macroeconomic stability, institutional and structural reforms, and mechanisms to strengthen the democratic process implementation capacity. 4. As approved by the Board on August 6, 2007, the pilot Board Technical Questions and Answer Database (http://boardqa.worldbank.org or from the EDs' portal) is now open for questions. -

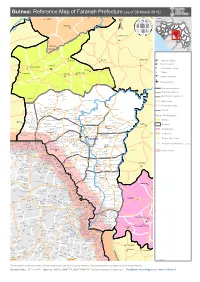

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (As of 05 March 2015)

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (as of 05 March 2015) Kalinko SENEGAL MALI GUINEA Sélouma BISSAU GUINEA Komola Koura COTE D'IVOIRE SIERRA LEONE Dialakoro Kankama LIBERIA Sisséla Sanguiana Bissikirima Regional Capital District Capital Dabola Arfamoussayah Sub District Capital Banko Kounendou Village Dogomet N'demba Unpaved runway Paved runway Region boundaries Koulambo District boundaries Morigbeya Dar Es Salam Daro Gada Walan Sub District boundaries Kindoyé DIGUILA CENTRE Fabouya TOUMANIA CENTRE Boubouya Main roads Yombo Nialen Moria Dansoya Secondary roads NIENOUYA CENTRE Teliayaga Doukou Passaya Souriya Mansira Moribaya KONDEBOU KASSA BOUNA CENTRE Tambaya Rivers Foya Gadha Mongoli Babakadia Hafia Gomboya BELEYA CENTRE SABERE KALIA Keema SOUNGBANYA CENTRE Balandou Beindougou SANSANKO CENTRE Sidakoro Gueagbely Gueafari Sokora District (Préfectures) Harounaya Miniandala Badhi Gnentin Oussouya Banire Wolofouga Lamiya Gueagbely Mameyire SANSAMBOU CENTRE BIRISSA CENTRE NGUENEYA CENTRE NIAKO CENTRE Koumandi Koura Dabola Wassakaria Kobalen Bingal Dansoya Tomata Konkofaya Heredou Marela karimbou Sansamba Bouran SOLOYA CENTRE Kolmatamba KOUMANDI KORO Sanamoussaya MILIDALA CENTRE Banfele Labatara Gninantamba BONTALA Koura Sambouya DIANA CENTRE Sansando Faranah Wossekalia FRIGUIA CENTRE MAGNA Halossagoya KALIA CENTRE I KOMBONYA Ballayany Herewa Alia Filly Fore Sakoromaya SOLONYEREYA Khamaya Bindou Dansaya Koutamodiya Salia Kamako Kissidougou Goulouya Fantoumaniya Nerekoro SEREKORO CENTRE Guidonya Kombonyady Wassambala Balankhamba Kabaya -

Omvg Energy Project Countries

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : OMVG ENERGY PROJECT COUNTRIES : MULTINATIONAL GAMBIA - GUINEA- GUINEA BISSAU - SENEGAL SUMMARY OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Team Members: Mr. A.B. DIALLO, Chief Energy Engineer, ONEC.1 Mr. P. DJAIGBE, Principal Financial Analyst, ONEC.1/SNFO Mr. K. HASSAMAL, Economist, ONEC.1 Mrs. S.MAHIEU, Socio-Economist, ONEC.1 Mrs. S.MAIGA, Procurement Officer, ORPF.1/SNFO Mr. O. OUATTARA, Financial Management Expert, ORPF.2/SNFO Mr. A.AYASI SALAWOU, Legal Consultant, GECL.1 Project Team Mr. M.L. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. H.P. SANON, Socio-Economist, ONEC.3 Sector Director: Mr. A.RUGUMBA, Director, ONEC Regional Director: Mr. J.K. LITSE, Acting Director, ORWA Division Manager: Mr. A.ZAKOU, Division Manager, ONEC.1, 1 OMVG ENERGY PROJECT Summary of ESIA Project Name : OMVG ENERGY PROJECT Country : MULTINATIONAL GAMBIA - GUINEA- GUINEA BISSAU - SENEGAL Project Ref. Number : PZ1-FAO-018 Department : ONEC Division: ONEC 1 1. INTRODUCTION This paper is the summary of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the OMVG Project, which was prepared in July 2014. This summary was drafted in accordance with the environmental requirements of the four OMVG countries and the African Development Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System for Category 1 projects. It starts with a presentation of the project description and rationale, followed by the legal and institutional frameworks of the four countries. Next, a description of the main environmental conditions of the project is presented along with project options which are compared in terms of technical, economic and social feasibility. -

Surveillance System Assessment in Guinea: Training Needed to Strengthen Data Quality and Analysis, 2016

PLOS ONE RESEARCH ARTICLE Surveillance system assessment in Guinea: Training needed to strengthen data quality and analysis, 2016 1 1 1,2 1,2 Doreen Collins , Sarah RheaID *, Boubacar Ibrahima Diallo , Mariama Boubacar Bah , Facinet Yattara3, Rachelle Goman Keleba4, Pia D. M. MacDonald1,5 1 RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, United States of America, 2 RTI International, Conakry, Guinea, 3 Guinea Ministry of Health, Conakry, Guinea, 4 International Organization for Migration, Boffa, Guinea, 5 Department of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North a1111111111 Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States of America a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract The 2014±2016 Ebola virus disease outbreak revealed the fragility of the Guinean public health infrastructure. As a result, the Guinean Ministry of Health is collaborating with interna- OPEN ACCESS tional partners to improve compliance with the International Health Regulations and work Citation: Collins D, Rhea S, Diallo BI, Bah MB, Yattara F, Keleba RG, et al. (2020) Surveillance toward the Global Health Security Agenda goals, including enhanced case- and community- system assessment in Guinea: Training needed to based disease surveillance. We assessed the case-based disease surveillance system strengthen data quality and analysis, 2016. PLoS during October 1, 2015±March 31, 2016, in the Boffa prefecture of Guinea. We conducted ONE 15(6): e0234796. https://doi.org/10.1371/ onsite interviews -

Sierra Leone – Prospects for Peace Severely Compromised

CONSOLIDATED INTER-AGENCY APPEALS FOR 2001 UNITED NATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL COPIES, PLEASE CONTACT: UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS PALAIS DES NATIONS 8-14 AVENUE DE LA PAIX CH - 1211 GENEVA, SWITZERLAND TEL.: (41 22) 917.1972 FAX: (41 22) 917.0368 E-MAIL: [email protected] THIS DOCUMENT CAN ALSO BE FOUND ON http://www.reliefweb.int/ TABLE OF CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 TABLE I :TOTAL FUNDING REQUIREMENTS - BY AGENCY AND COUNTRY ........................................3 TABLE II: SUMMARY OF REQUIREMENTS BY SECTOR AND APPEALING AGENCY............................4 SUB-REGIONAL OVERVIEW......................................................................................................... 5 1. Background .......................................................................................................................... 5 2. Impact on the humanitarian situation ................................................................................... 5 3. Regional and International Response .................................................................................. 6 4. Sub-regional Linkages.......................................................................................................... 7 5. Sub-regional Challenges......................................................................................................8 6. Rationale for a Sub-regional and Multi-disciplinary Approach ............................................ -

Guinea: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper

REPUBLIC OF GUINEA Work – Justice – Solidarity Ministry of the Economy, Finances and Planning Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2 (2007–2010) Conakry, August 2007 Permanent Secretariat for the Poverty Reduction Strategy (SP-SRP) Website: www.srp-guinee.org.Telephone: (00224) 30 43 10 80. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document is the fruit of a collective effort that has involved many development stakeholders: executives of regionalized and decentralized structures, civil society organizations, development partners, etc. Warm thanks to all of them. The government would particularly like to acknowledge the grassroots organizations and civil society actors who, despite the difficulties that affected the implementation of the PRSP-I, have renewed their confidence in its action. The lessons learned from the implementation of the PRSP-I have helped in the design and preparation of the document. For this, the government again thanks the development partners who have accompanied it in this exercise and provided technical and financial contributions (EU, GTZ, SCAC, Canadian Cooperation), as well as the team of national experts who carried out field work with dedication and professionalism. Furthermore, without the painstaking work carried out in 2005 and 2006 as part of the process of refining the regional PRSPs, it certainly would not have been possible to prepare this document. The same is true of the work done, mainly in 2006, to evaluate needs aimed at reaching the MDGs. In this regard, we thank the United Nations System, and in particular the UNDP, for its exceptional contribution. Finally, the government extends its most sincere thanks to all those, both named and unnamed, who participated in this collective work. -

Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2

© 2008 International Monetary Fund January 2008 IMF Country Report No. 08/7 Guinea: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) are prepared by member countries in broad consultation with stakeholders and development partners, including the staffs of the World Bank and the IMF. Updated every three years with annual progress reports, they describe the country's macroeconomic, structural, and social policies in support of growth and poverty reduction, as well as associated external financing needs and major sources of financing. This country document for Guinea, dated August 2007, is being made available on the IMF website by agreement with the member country as a service to users of the IMF website. To assist the IMF in evaluating the publication policy, reader comments are invited and may be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. Copies of this report are available to the public from International Monetary Fund • Publication Services 700 19th Street, N.W. • Washington, D.C. 20431 Telephone: (202) 623-7430 • Telefax: (202) 623-7201 E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.imf.org Price: $18.00 a copy International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution This page intentionally left blank ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution REPUBLIC OF GUINEA Work – Justice – Solidarity Ministry of the Economy, Finances and Planning Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper PRSP–2 (2007–2010) Conakry, August 2007 Permanent Secretariat for the Poverty Reduction Strategy (SP-SRP) Website: www.srp-guinee.org.Telephone: (00224) 30 43 10 80. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document is the fruit of a collective effort that has involved many development stakeholders: executives of regionalized and decentralized structures, civil society organizations, development partners, etc. -

Climate Change Analysis for Guinea Conakry with Homogenized Daily Dataset

CLIMATE CHANGE ANALYSIS FOR GUINEA CONAKRY WITH HOMOGENIZED DAILY DATASET. Abdoul Aziz Barry Dipòsit Legal: T 262-2015 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

RAZC Project Final Evaluation Report VF 2016.Pdf

REPUBLIC OF GUINEA Work –Justice -Solidarity MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, WATER AND FORESTS ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY TERMINAL EVALUATION REPORT RACZ PROJECT « Strengthening resilience and adaptation to negative impacts of climate change in Guinea's vulnerable coastal zones » Developed by: . Mr. Yadh LABANE, International Consultant, Team Leader . Mr. Ahmed Faya Traore, National Consultant Version 0.1 02 November 2016 Pre-final version 11 November 2016 Final version 09 December 2016 CONTENTS i. OPENING PAGE ................................................................................................................................................... i ii. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... ii 1. PROJECT SUMMARY TABLE ........................................................................................................................ ii 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................................ ii 3. EVALUATION RATING TABLE ................................................................................................................... iii 4. SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND LESSONS ............................................. iii iii. ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... -

Evaluation of the Hydroenergetic Potential of the Fall from Kalako to Dabola, Guinea

International Journal of Advanced Research and Publications ISSN: 2456-9992 Evaluation Of The Hydroenergetic Potential Of The Fall From Kalako To Dabola, Guinea. Doussou Lancine TRAORE, Yacouba CAMARA, Ansoumane SAKOUVOGUI, Mamby KEITA Polytechnic Institute, Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry - Guinea, Energy Department, Higher Institute of Technology of Mamou - Guinea, Department of Physics, Faculty of Sciences, Gamal Abdel Nasser University of Conakry - Guinea, Traoredl54 @ gmail.com, +224 628 991426 [email protected], +224 622288295 [email protected], +224 628016168 [email protected], +224 622681932 Abstract: The hydro-energetic potential of the Kalako site on the Tinkisso River in Dabola prefecture, evaluated by the spot measurement method during the month of March (dry season) is 5085.50 kW, or about 5.1 MW. This value is in the range of mini hydroelectric plants. The values of the evaluation parameters of this hydroenergetic potential at this time are: the depth of the watercourse (0.58 m), the flow velocity (1.46 m/s), the flow rate (14.4 m3/s), the drop height (60 m) and the efficiency of the electromechanical equipment (60%). Such a regular assessment of the hydroelectric potential of all waterfalls available in the country would provide a reliable database on the existing hydroelectric potential, hence the objective of this research. Key words: Assessment, potential, hydropower, useful power. 1.Introduction these hydroelectric potentials is often based on analyzes of Hydroelectric power is a renewable energy obtained by meteorological and hydrological data over a long period (25 converting the hydraulic energy of the various natural water to 50 years). It turns out that for most of these sites in flows into electricity. -

Ecologically Sensitive Sites in Africa. Volume 1

Ecologically Sites in Africa Volume I: Occidental and Central Africa Benin Cameroon Central African Republic Congo Cdte d'lvoire Eq uatorlil^lllpvea aSon Guinea Complled'by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre For TK^^o^d Bdnk Ecologically Sensitive Sites in Africa Volume I: Occidental and Central Africa WORLD CONSERVATION! MONITORING CENTRE 2 4 MAY 1995 Compiled by PROTECTED AREAS | World Conservation Monitoring Centre Cambridge, UK for The World Bank Washington DC, USA The World Bank 1993 Published by The World Bank, Washington, DC, USA. Prepared by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL, UK. WCMC is a joint venture between the three partners who developed The World Conservation Strategy and its successor Caring for the Earth: lUCN-World Conservation Union, UNEP-United Nations Environment Programme, and WWF- World Wide Fund for Nature. Its mission is to provide an information, research and assessment service on the status, security and management of the Earth's biological diversity as the basis for its conservation and sustainable use. Copyright: 1993 The World Bank Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior permission from the copyright holder. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: World Bank (1993). Ecologically Sensitive Sites in Africa. Volume I: Occidental and Central Africa. Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre for The World Bank, Washington, DC, USA. Printed by: The Burlington Press, Cambridge, UK. Cover illustration: Nairobi City Skyline with Kongoni and Grant's Gazelles, RIM Campbell. -

NEW KAPORO FISH LANDING FACILITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 5-5 New Kaporo Fish Landing Facility Development Project

NEW KAPORO FISH LANDING FACILITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 5-5 New Kaporo Fish Landing Facility Development Project 5-5-1 Outline Both Kaporo and the adjacent Nongo fish landing beaches are located on the northern shore of the central part of the Conakry Peninsula and they are the farthest east of all coastal fishery bases on this peninsula. This area is located at the mouth of Kaporo River, known as the place where Lusitanian people first visited the Conakry Peninsula and where a fishing settlement was established very early. Comparison of fishery statistics of 1992 and 1998 shows a temporary decrease in the number of fishing boats operating at Kaporo and Nongo fish landing beaches toward the latter part of the 1990s. This is considered to be attributable to the advance of general city residents into this region at around the same time due to development of urbanization and to a (temporary) shift of fishing boats from Kaporo and Nongo regions to other fish landing beaches on the Conakry Peninsula due to active development of fishery bases under ODEPAG (Guinea Artisanal Fishery Development Plan). On the contrary, in recent years the number of fishing boats operating in Kaporo and Nongo regions drastically increased (by 57 boats – about 65% in the 4 years since 1998) and the current number of boats operating is 170. This is considered to have resulted from the geographical superiority of this region as an urban fish landing spot in view of increased needs for fishery products in this region and proximity to consumer markets under situations where the population of Conakry has increased and sprawled to the central as well as eastern parts of the Conakry Peninsula.