Big Farms Make Big Flu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compendium of the Findings of the OPCAST Pandemic Subgroup 12

1 A Compendium of the Findings of the Obama PCAST Ad Hoc Subgroup on Pandemic Preparedness and Response December 23, 2020 Introduction A subset of the former members of President Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (here OPCAST)—ten individuals who played particularly important roles in producing the six OPCAST reports between 2009 and 2016 that dealt with issues related to pandemic preparedness and response1—came together starting in March of this year to consider how insights from those studies might be combined with more recent research and current observations to develop suggestions about how the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic could be improved. The Subgroup has produced six reports, addressing • the national strategic pandemic-response stockpile (May 20) • the role of contact tracing (June 18) • the role of public health data in controlling the spread of COVID-19 (July 28) • testing for the pathogen (August 18) • recommendations for the coming COVID-19 commission (September 21) • needs for improved epidemiological modeling (September 28) Each report was distributed, upon completion, to selected members of the Trump COVID-19 team and the Biden campaign staff, selected governors and members of Congress, selected public health experts outside government, and the media. The reports have also been posted on the OPCAST team’s website, http://opcast.org, together with a few opinion pieces based on them. In the current volume, we have assembled all six reports in full, preceded by a set of brief summaries. Four of the reports are followed by short updates taking account of developments since the reports first came out. -

US and International Responses to the Global Spread of Avian

Order Code RL33219 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web U.S. and International Responses to the Global Spread of Avian Flu: Issues for Congress Updated February 23, 2006 Tiaji Salaam-Blyther and Emma Chanlett-Avery Coordinators Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress U.S. and International Responses to the Global Spread of Avian Flu: Issues for Congress Summary One strain of avian influenza currently identified in Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa is known as Influenza A/H5N1. Although it is a bird flu, it has infected a relatively small number of people — killing around 50% of those infected. Some scientists are concerned that H5N1 may cause the next influenza pandemic. Flu pandemics have occurred cyclically, between every 30 and 50 years. Since 1997, when the first human contracted H5N1 in Hong Kong, the virus has resurfaced and spread to more than a dozen countries in Asia and eastern Europe — infecting more than 170 people and killing more than 90. In February 2006, the virus spread further to countries in western Europe. That month, officials confirmed that birds in Austria, Germany, Greece, and Italy were infected with the virus. Health experts are investigating suspected bird cases in France. The first human H5N1 fatalities outside of Asia occurred in 2006 when Turkey and Iraq announced their first human deaths related to H5N1 infection in January 2006 and February 2006, respectively. A global influenza pandemic could have a number of consequences. Global competition for existing vaccines and treatments could ensue. Some governments might restrict the export of vaccines or other supplies in order to treat their own population. -

Studies of the Laboulbeniomycetes: Diversity, Evolution, and Patterns of Speciation

Studies of the Laboulbeniomycetes: Diversity, Evolution, and Patterns of Speciation The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40049989 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! STUDIES OF THE LABOULBENIOMYCETES: DIVERSITY, EVOLUTION, AND PATTERNS OF SPECIATION A dissertation presented by DANNY HAELEWATERS to THE DEPARTMENT OF ORGANISMIC AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Biology HARVARD UNIVERSITY Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2018 ! ! © 2018 – Danny Haelewaters All rights reserved. ! ! Dissertation Advisor: Professor Donald H. Pfister Danny Haelewaters STUDIES OF THE LABOULBENIOMYCETES: DIVERSITY, EVOLUTION, AND PATTERNS OF SPECIATION ABSTRACT CHAPTER 1: Laboulbeniales is one of the most morphologically and ecologically distinct orders of Ascomycota. These microscopic fungi are characterized by an ectoparasitic lifestyle on arthropods, determinate growth, lack of asexual state, high species richness and intractability to culture. DNA extraction and PCR amplification have proven difficult for multiple reasons. DNA isolation techniques and commercially available kits are tested enabling efficient and rapid genetic analysis of Laboulbeniales fungi. Success rates for the different techniques on different taxa are presented and discussed in the light of difficulties with micromanipulation, preservation techniques and negative results. CHAPTER 2: The class Laboulbeniomycetes comprises biotrophic parasites associated with arthropods and fungi. -

PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II

OFFICIAL USE ONLY IDA/SecM2007-0684 December 12, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized For meeting of Board: Tuesday, January 8, 2008 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Guinea: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note 1. Attached is the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II. The IMF is currently scheduled to discuss this document on December 21, 2007. 2. The PRSP II was prepared by the Government of Guinea. The paper acknowledges the disappointing outcome of the first PRSP, which covered the period 2002-2006. The political, social and economic environment in which the implementation of PRSP I took place was characterized by poor governance, political instability, and low growth which led to an increase in poverty from 49 percent in 2002 to an estimated 54 percent in 2005. Overall, public service delivery deteriorated in terms of both quality and access and the living conditions for most Guineans worsened. Public Disclosure Authorized 3. PRSP II aims at recapturing lost ground over the past five years. The overall strategy is based on three pillars: (i) improving governance; (ii) accelerating growth and increasing employment opportunities; and (iii) improving access to basic services. It focuses on restoring macroeconomic stability, institutional and structural reforms, and mechanisms to strengthen the democratic process implementation capacity. 4. As approved by the Board on August 6, 2007, the pilot Board Technical Questions and Answer Database (http://boardqa.worldbank.org or from the EDs' portal) is now open for questions. -

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared by the University of Washington Quantum System Engineering (QSE) Group.1 Bibliography [1] Mu A-Hua, Zhou Shao-Lei, and Yu Xiao-Li. Research on fast self-adaptive genetic algorithm and its simulation. Journal of System Simulation, 16(1):122 – 5, 2004. [2] Guan Ai-Jie, Yu Da-Tai, Wang Yun-Ji, An Yue-Sheng, and Lan Rong-Qin. Simulation of recon-sat reconing process and evaluation of reconing effect. Journal of System Simulation, 16(10):2261 – 3, 2004. [3] Hao Ai-Min, Pang Guo-Feng, and Ji Yu-Chun. Study and implementation for fidelity of air roaming system above the virtual mount qomolangma. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):356 – 9, 2000. [4] Sui Ai-Na, Wu Wei, and Zhao Qin-Ping. The analysis of the theory and technology on virtual assembly and virtual prototype. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):386 – 8, 2000. [5] Xu An, Fan Xiu-Min, Hong Xin, Cheng Jian, and Huang Wei-Dong. Research and development on interactive simulation system for astronauts walking in the outer space. Journal of System Simulation, 16(9):1953 – 6, Sept. 2004. [6] Zhang An and Zhang Yao-Zhong. Study on effectiveness top analysis of group air-to-ground aviation weapon system. Journal of System Simulation, 14(9):1225 – 8, Sept. 2002. [7] Zhang An, He Sheng-Qiang, and Lv Ming-Qiang. Modeling simulation of group air-to-ground attack-defense confrontation system. Journal of System Simulation, 16(6):1245 – 8, 2004. [8] Wu An-Bo, Wang Jian-Hua, Geng Ying-San, and Wang Xiao-Feng. -

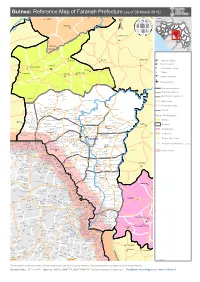

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (As of 05 March 2015)

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (as of 05 March 2015) Kalinko SENEGAL MALI GUINEA Sélouma BISSAU GUINEA Komola Koura COTE D'IVOIRE SIERRA LEONE Dialakoro Kankama LIBERIA Sisséla Sanguiana Bissikirima Regional Capital District Capital Dabola Arfamoussayah Sub District Capital Banko Kounendou Village Dogomet N'demba Unpaved runway Paved runway Region boundaries Koulambo District boundaries Morigbeya Dar Es Salam Daro Gada Walan Sub District boundaries Kindoyé DIGUILA CENTRE Fabouya TOUMANIA CENTRE Boubouya Main roads Yombo Nialen Moria Dansoya Secondary roads NIENOUYA CENTRE Teliayaga Doukou Passaya Souriya Mansira Moribaya KONDEBOU KASSA BOUNA CENTRE Tambaya Rivers Foya Gadha Mongoli Babakadia Hafia Gomboya BELEYA CENTRE SABERE KALIA Keema SOUNGBANYA CENTRE Balandou Beindougou SANSANKO CENTRE Sidakoro Gueagbely Gueafari Sokora District (Préfectures) Harounaya Miniandala Badhi Gnentin Oussouya Banire Wolofouga Lamiya Gueagbely Mameyire SANSAMBOU CENTRE BIRISSA CENTRE NGUENEYA CENTRE NIAKO CENTRE Koumandi Koura Dabola Wassakaria Kobalen Bingal Dansoya Tomata Konkofaya Heredou Marela karimbou Sansamba Bouran SOLOYA CENTRE Kolmatamba KOUMANDI KORO Sanamoussaya MILIDALA CENTRE Banfele Labatara Gninantamba BONTALA Koura Sambouya DIANA CENTRE Sansando Faranah Wossekalia FRIGUIA CENTRE MAGNA Halossagoya KALIA CENTRE I KOMBONYA Ballayany Herewa Alia Filly Fore Sakoromaya SOLONYEREYA Khamaya Bindou Dansaya Koutamodiya Salia Kamako Kissidougou Goulouya Fantoumaniya Nerekoro SEREKORO CENTRE Guidonya Kombonyady Wassambala Balankhamba Kabaya -

Detection Technologies, Part 2

www.engineeringvillage.com Citation results: 500 Downloaded: 4/24/2020 1. RESPIRATORY NITRIC OXIDE METER MAULT JAMES R Assignee: HEALTHETECH INC Publication Number: WO126547 Publication date: 06/07/2001 Kind: CORRECTED TITLE PAGE OF AN EP-A DOCUMENT Database: WO Patents Compilation and indexing terms, 2020 LexisNexis Univentio B.V. Data Provider: Engineering Village 2. RESPIRATORY NITRIC OXIDE METER MAULT JAMES R Assignee: HEALTHETECH INC Publication Number: WO126547 Publication date: 04/19/2001 Kind: Patent Application Publication Database: WO Patents Compilation and indexing terms, 2020 LexisNexis Univentio B.V. Data Provider: Engineering Village 3. RESPIRATORY THERAPY APPARATUS AND METHODS KHASAWNEH, Mohammad, Qassim, Mohammad; SAGOO, Jeevan; VARNEY, Mark, Sinclair Assignee: SMITHS MEDICAL INTERNATIONAL LIMITED Publication Number: WO2015036723 Publication date: 03/19/2015 Kind: Patent Application Publication Database: WO Patents Compilation and indexing terms, 2020 LexisNexis Univentio B.V. Data Provider: Engineering Village 4. RESPIRATORY THERAPY APPARATUS AND METHODS BENNETT, Paul James Leslie Assignee: SMITHS MEDICAL INTERNATIONAL LIMITED Publication Number: WO2014202923 Publication date: 12/24/2014 Kind: Patent Application Publication Database: WO Patents Compilation and indexing terms, 2020 LexisNexis Univentio B.V. Data Provider: Engineering Village 5. RESPIRATORY THERAPY APPARATUS AND METHODS Khasawneh, Mohammad Qassim Mohammad; Sagoo, Jeevan; Varney, Mark Sinclair Assignee: SMITHS MEDICAL INTERNATIONAL LIMITED Publication Number: US20160213868 Publication date: 07/28/2016 Kind: Patent Application Publication Database: US Patents Compilation and indexing terms, 2020 LexisNexis Univentio B.V. Data Provider: Engineering Village 6. RESPIRATORY THERAPY APPARATUS AND METHODS BENNETT, Paul James Leslie Assignee: Smiths Medical International Limited Publication Number: EP3010396 Publication date: 04/27/2016 Kind: Patent Application Publication Database: EP Patents Compilation and indexing terms, 2020 LexisNexis Univentio B.V. -

A Thesis Entitled Influence of Soil-Quality on Coffee-Plant Quality

A Thesis entitled Influence of Soil-Quality on Coffee-Plant Quality and a Complex Tropical Insect Food Web by David J. Gonthier Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Biology (Ecology track) Dr. Stacy Philpott, Committee Chair Dr. Scott Heckathorn, Committee Member Dr. Ivette Perfecto, Committee Member Dr. Patricia Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo May 2010 Copyright 2010, David J. Gonthier This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Influence of Soil-Quality on Coffee-Plant Quality and a Complex Tropical Insect Food Web by David J. Gonthier Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Biology (Ecology track) The University of Toledo May 2010 Tropical systems are complex, species diverse, and are often regulated by top-down forces (higher trophic levels control lower trophic levels). In many ecosystems insects, especially herbivores and their mutualists, may be strongly affected by plant quality and other bottom-up controls (nutrient availability, plant genetic variation, ect.). Yet few have asked how plant quality (nutritional and defensive plant traits) can contribute to the population regulation and the complexity of these systems. In this thesis, I investigate the importance of soil-quality to both the elemental and secondary metabolite content in coffee and ask how changes to plant quality can influence hemipteran herbivores, their ant-mutualists, predators, and insect communities in a tropical coffee agroecosystem. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

MERS-Cov Data Sharing Case Study Report November 2018

MERS-CoV Data Sharing Case Study Report November 2018 1. Introduction a. Background to the ongoing MERS-CoV outbreak: In September 2012, Dr Ali Mohamed Zaki reported the isolation of a novel betacoronavirus on ProMED-mail, the internet infectious disease alert system run by the International Society for Infectious Diseases.1 The patient, a 60-year-old male from Saudi Arabia presenting with pneumonia- like symptoms died from an unknown viral infection in June 2012.2 Later dubbed the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV),3 this emerging infectious disease has now been responsible for more than 2,200 laboratory-confirmed infections in people from 27 countries, and close to 800 deaths.4 The vast majority of these cases have been recorded in Saudi Arabia, however MERS-CoV is considered a severe emerging disease with the potential to cause a major global health emergency.5 Epidemiological investigations have revealed that primary human infections with MERS-CoV are often, but not always associated with contact with dromedary camels around the Arabian Peninsula.6 Human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV has been responsible for case clusters in family groups and healthcare facilities. The incidence of hospital-acquired infections have been reduced with the employment of strict infection control measures,7 and the international public health community remain on high alert for new introductions. In 2015, South Korea saw the largest outbreak of MERS- CoV outside of the Eastern Mediterranean with 186 confirmed cases and 38 deaths.7 New cases of MERS-CoV infection continue to be reported mostly from the Eastern Mediterranean. -

Wax Structures of Scymnus Louisianae Attenuate Aggression from Aphid-Tending Ants

CHEMICAL ECOLOGY Wax Structures of Scymnus louisianae Attenuate Aggression From Aphid-Tending Ants EZRA G. SCHWARTZBERG,1,2 KENNETH F. HAYNES,1 DOUGLAS W. JOHNSON,1 1 AND GRAYSON C. BROWN Environ. Entomol. 39(4): 1309Ð1314 (2010); DOI: 10.1603/EN09372 ABSTRACT The cuticular wax structures of Scymnus louisianae J. Chapin larvae were investigated as a defense against ant aggression by Lasius neoniger Emery. The presence of wax structures provided signiÞcant defense against ant aggression compared with denuded larvae in that these structures attenuated the aggressive behavior of foraging ants. Furthermore, reapplication of wax dissolved in hexane partially restored defenses associated with intact structures, showing an attenuation of aggression based in part on cuticular wax components rather than solely on physical obstruction to ant mouthparts. KEY WORDS Scymnus louisianae, Aphis glycines, Lasius neoniger, ant-tending Many ants tend aphids and use the collected honeydew wax in promoting physical obstruction to the mouthparts as a sugar source. In return, the aphids beneÞt from the of aphid-tending ants, little has been done to elucidate tending ants (Way 1963, Ho¨lldobler and Wilson 1990). In the role that wax plays in eliciting avoidance behavior or these systems, aphids can beneÞt through reduced pre- in attenuating aggression. SpeciÞcally, physical or chem- dation (Banks 1962) and increased Þtness (Flatt and ical mimicry, camoußage, or repellency has not been Weisser 2000). The relationship between ants and aphids looked at as a potential means of avoidance of ant ag- is often a mutualistic one but ranges from obligatory to gression in the Scymnus beetles. It has been suggested facultative (Dixon 1998). -

Sierra Leone – Prospects for Peace Severely Compromised

CONSOLIDATED INTER-AGENCY APPEALS FOR 2001 UNITED NATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL COPIES, PLEASE CONTACT: UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS PALAIS DES NATIONS 8-14 AVENUE DE LA PAIX CH - 1211 GENEVA, SWITZERLAND TEL.: (41 22) 917.1972 FAX: (41 22) 917.0368 E-MAIL: [email protected] THIS DOCUMENT CAN ALSO BE FOUND ON http://www.reliefweb.int/ TABLE OF CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 TABLE I :TOTAL FUNDING REQUIREMENTS - BY AGENCY AND COUNTRY ........................................3 TABLE II: SUMMARY OF REQUIREMENTS BY SECTOR AND APPEALING AGENCY............................4 SUB-REGIONAL OVERVIEW......................................................................................................... 5 1. Background .......................................................................................................................... 5 2. Impact on the humanitarian situation ................................................................................... 5 3. Regional and International Response .................................................................................. 6 4. Sub-regional Linkages.......................................................................................................... 7 5. Sub-regional Challenges......................................................................................................8 6. Rationale for a Sub-regional and Multi-disciplinary Approach ............................................