Guinea PEA FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona Fishing Regulations 3 Fishing License Fees Getting Started

2019 & 2020 Fishing Regulations for your boat for your boat See how much you could savegeico.com on boat | 1-800-865-4846insurance. | Local Offi ce geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | Local Offi ce See how much you could save on boat insurance. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. TowBoatU.S. is the preferred towing service provider for GEICO Marine Insurance. The GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2017. © 2017 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 2 12/4/2018 1:14:48 PM AdPages2019.indd 3 12/4/2018 1:17:19 PM Table of Contents Getting Started License Information and Fees ..........................................3 Douglas A. Ducey Governor Regulation Changes ...........................................................4 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH COMMISSION How to Use This Booklet ...................................................5 JAMES S. ZIELER, CHAIR — St. Johns ERIC S. SPARKS — Tucson General Statewide Fishing Regulations KURT R. DAVIS — Phoenix LELAND S. “BILL” BRAKE — Elgin Bag and Possession Limits ................................................6 JAMES R. AMMONS — Yuma Statewide Fishing Regulations ..........................................7 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT Common Violations ...........................................................8 5000 W. Carefree Highway Live Baitfish -

Programme and Abstracts THANKS to OUR SPONSORS!

5th Pan-European Duck Symposium 16th-20th April 2018 Isle of Great Cumbrae, Scotland Programme and Abstracts THANKS TO OUR SPONSORS! 2 ORGANISING COMMITTEE Chris Waltho (Independent Researcher) Colin A Galbraith (Colin Galbraith Environment Consultancy) Richard Hearn (Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust / Duck Specialist Group) Matthieu Guillemain (Office National de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage / Duck Specialist Group) SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Tony Fox (University of Aarhus) Colin A Galbraith (Colin Galbraith Environment Consultancy) Andy J Green (Estación Biológica de Doñana) Matthieu Guillemain (Office National de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage / DSG) Richard Hearn (Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust / Duck Specialist Group) Sari Holopainen (University of Helsinki) Mika Kilpi (Novia University of Applied Sciences) Carl Mitchell (Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust) David Rodrigues (Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra) Diana Solovyeva (Russian Academy of Sciences) Chris Waltho (Independent Researcher) 3 PROGRAMME Monday 16th April: Pre- meeting Workshop on marine issues 11.00 – 16.00. DAY1 (Tuesday 17th April) Chair: Chris Waltho 9:00 – 9:05 Chris Waltho – Welcome. 9:05 – 9:10 Provost Ian Clarkson - North Ayrshire Council. 9:10 – 9:20 Lady Isobel Glasgow - Chair of the Clyde Marine Planning Partnership. 9:20 – 9:30 Colin Galbraith – The aims and objectives of the Conference. 9:30 – 10:20 Plenary 1 Dr. Jacques Trouvilliez, (Executive Secretary of the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA)) 10:20 - 10:45 Coffee break SESSION 1 POPULATION DYNAMICS AND TRENDS Chair: Colin Galbraith 10:45 – 11:00 New pan-European data on the breeding distribution of ducks. Verena Keller, Martí Franch, Sergi Herrando, Mikhail Kalyakin, Olga Voltzit and Petr Voříšek 11:00 – 11:15 Trends in breeding waterbird guild richness in the southwestern Mediterranean: an analysis over 12 years (2005-2017). -

JPC.CCP Bureau Du Prdsident

Onchoccrciasis Control Programmc in the Volta Rivcr Basin arca Programme de Lutte contre I'Onchocercose dans la R6gion du Bassin de la Volta JOIN'T PROCRAMME COMMITTEE COMITE CONJOINT DU PROCRAMME Officc of the Chuirrrran JPC.CCP Bureau du Prdsident JOINT PROGRAII"IE COMMITTEE JPC3.6 Third session ORIGINAL: ENGLISH L Bamako 7-10 December 1982 October 1982 Provisional Agenda item 8 The document entitled t'Proposals for a Western Extension of the Prograncne in Mali, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ssnegal and Sierra Leone" was reviewed by the Corrrittee of Sponsoring Agencies (CSA) and is now transmitted for the consideration of the Joint Prograurne Conrnittee (JPC) at its third sessior:. The CSA recalls that the JPC, at its second session, following its review of the Feasibility Study of the Senegal River Basin area entitled "Senegambia Project : Onchocerciasis Control in Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, l,la1i, Senegal and Sierra Leone", had asked the Prograrrne to prepare a Plan of Operations for implementing activities in this area. It notes that the Expert Advisory Conrnittee (EAC) recormnended an alternative strategy, emphasizing the need to focus, in the first instance, on those areas where onchocerciasis was hyperendemic and on those rivers which were sources of reinvasion of the present OCP area (Document JPC3.3). The CSA endorses the need for onchocerciasis control in the Western extension area. However, following informal consultations, and bearing in mind the prevailing financial situation, the CSA reconrnends that activities be implemented in the area on a scale that can be managed by the Prograrmne and at a pace concomitant with the availability of funds, in order to obtain the basic data which have been identified as missing by the proposed plan of operations. -

The Lost & Found Children of Abraham in Africa and The

SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International The Lost & Found Children of Abraham In Africa and the American Diaspora The Saga of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ & Their Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination by Abu Alfa Umar MUHAMMAD SHAREEF bin Farid 0 Copyright/2004- Muhammad Shareef SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/www,siiasi.org All rights reserved Cover design and all maps and illustrations done by Muhammad Shareef 1 SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/ www.siiasi.org ﺑِ ﺴْ ﻢِ اﻟﻠﱠﻪِ ا ﻟ ﺮﱠ ﺣْ ﻤَ ﻦِ ا ﻟ ﺮّ ﺣِ ﻴ ﻢِ وَﺻَﻠّﻰ اﻟﻠّﻪُ ﻋَﻠَﻲ ﺳَﻴﱢﺪِﻧَﺎ ﻣُ ﺤَ ﻤﱠ ﺪٍ وﻋَﻠَﻰ ﺁ ﻟِ ﻪِ وَ ﺻَ ﺤْ ﺒِ ﻪِ وَ ﺳَ ﻠﱠ ﻢَ ﺗَ ﺴْ ﻠِ ﻴ ﻤ ﺎً The Turudbe’ Fulbe’: the Lost Children of Abraham The Persistence of Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. The Origin of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 4. Social Stratification of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 5. The Turudbe’ and the Diffusion of Islam in Western Bilad’’s-Sudan 6. Uthman Dan Fuduye’ and the Persistence of Turudbe’ Historical Consciousness 7. The Asabiya (Solidarity) of the Turudbe’ and the Philosophy of History 8. The Persistence of Turudbe’ Identity Construct in the Diaspora 9. The ‘Lost and Found’ Turudbe’ Fulbe Children of Abraham: The Ordeal of Slavery and the Promise of Redemption 10. Conclusion 11. Appendix 1 The `Ida`u an-Nusuukh of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 12. Appendix 2 The Kitaab an-Nasab of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 13. -

Are the Fouta Djallon Highlands Still the Water Tower of West Africa?

water Article Are the Fouta Djallon Highlands Still the Water Tower of West Africa? Luc Descroix 1,2,*, Bakary Faty 3, Sylvie Paméla Manga 2,4,5, Ange Bouramanding Diedhiou 6 , Laurent A. Lambert 7 , Safietou Soumaré 2,8,9, Julien Andrieu 1,9, Andrew Ogilvie 10 , Ababacar Fall 8 , Gil Mahé 11 , Fatoumata Binta Sombily Diallo 12, Amirou Diallo 12, Kadiatou Diallo 13, Jean Albergel 14, Bachir Alkali Tanimoun 15, Ilia Amadou 15, Jean-Claude Bader 16, Aliou Barry 17, Ansoumana Bodian 18 , Yves Boulvert 19, Nadine Braquet 20, Jean-Louis Couture 21, Honoré Dacosta 22, Gwenaelle Dejacquelot 23, Mahamadou Diakité 24, Kourahoye Diallo 25, Eugenia Gallese 23, Luc Ferry 20, Lamine Konaté 26, Bernadette Nka Nnomo 27, Jean-Claude Olivry 19, Didier Orange 28 , Yaya Sakho 29, Saly Sambou 22 and Jean-Pierre Vandervaere 30 1 Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, UMR PALOC IRD/MNHN/Sorbonne Université, 75231 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 LMI PATEO, UGB, St Louis 46024, Senegal; [email protected] (S.P.M.); [email protected] (S.S.) 3 Direction de la Gestion et de la Planification des Ressources en Eau (DGPRE), Dakar 12500, Senegal; [email protected] 4 Département de Géographie, Université Assane Seck de Ziguinchor, Ziguinchor 27000, Senegal 5 UFR des Sciences Humaines et Sociales, Université de Lorraine, 54015 Nancy, France 6 Master SPIBES/WABES Project (Centre d’Excellence sur les CC) Bingerville, Université Félix Houphouët Boigny, 582 Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire; [email protected] 7 Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, -

PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II

OFFICIAL USE ONLY IDA/SecM2007-0684 December 12, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized For meeting of Board: Tuesday, January 8, 2008 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Guinea: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note 1. Attached is the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II. The IMF is currently scheduled to discuss this document on December 21, 2007. 2. The PRSP II was prepared by the Government of Guinea. The paper acknowledges the disappointing outcome of the first PRSP, which covered the period 2002-2006. The political, social and economic environment in which the implementation of PRSP I took place was characterized by poor governance, political instability, and low growth which led to an increase in poverty from 49 percent in 2002 to an estimated 54 percent in 2005. Overall, public service delivery deteriorated in terms of both quality and access and the living conditions for most Guineans worsened. Public Disclosure Authorized 3. PRSP II aims at recapturing lost ground over the past five years. The overall strategy is based on three pillars: (i) improving governance; (ii) accelerating growth and increasing employment opportunities; and (iii) improving access to basic services. It focuses on restoring macroeconomic stability, institutional and structural reforms, and mechanisms to strengthen the democratic process implementation capacity. 4. As approved by the Board on August 6, 2007, the pilot Board Technical Questions and Answer Database (http://boardqa.worldbank.org or from the EDs' portal) is now open for questions. -

A VISION of WEST AFRICA in the YEAR 2020 West Africa Long-Term Perspective Study

Millions of inhabitants 10000 West Africa Wor Long-Term Perspective Study 1000 Afr 100 10 1 Yea 1965 1975 1850 1800 1900 1950 1990 2025 2000 Club Saheldu 2020 % of the active population 100 90 80 AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 70 60 50 40 30 NON AGRICULTURAL “INFORMAL” SECTOR 20 10 NON AGRICULTURAL 3MODERN3 SECTOR 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 Preparing for 2020: 6 000 towns of which 300 have more than 100 000 inhabitants Production and total availability in gigaczalories per day Import as a % of availa 500 the Future 450 400 350 300 250 200 A Vision of West Africa 150 100 50 0 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 Imports as a % of availability Total food availability Regional production in the Year 2020 2020 CLUB DU SAHEL PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE A VISION OF WEST AFRICA IN THE YEAR 2020 West Africa Long-Term Perspective Study Edited by Jean-Marie Cour and Serge Snrech ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ FOREWoRD ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ In 1991, four member countries of the Club du Sahel: Canada, the United States, France and the Netherlands, suggested that a regional study be undertaken of the long-term prospects for West Africa. Several Sahelian countries and several coastal West African countries backed the idea. To carry out this regional study, the Club du Sahel Secretariat and the CINERGIE group (a project set up under a 1991 agreement between the OECD and the African Development Bank) formed a multi-disciplinary team of African and non-African experts. -

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel

Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY 1 2 Pastoralism and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Towards Peaceful Coexistence UNOWAS STUDY August 2018 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations p.8 Chapter 3: THE REPUBLIC OF MALI p.39-48 Acknowledgements p.9 Introduction Foreword p.10 a. Pastoralism and transhumance UNOWAS Mandate p.11 Pastoral Transhumance Methodology and Unit of Analysis of the b. Challenges facing pastoralists Study p.11 A weak state with institutional constraints Executive Summary p.12 Reduced access to pasture and water Introductionp.19 c. Security challenges and the causes and Pastoralism and Transhumance p.21 drivers of conflict Rebellion, terrorism, and the Malian state Chapter 1: BURKINA FASO p.23-30 Communal violence and farmer-herder Introduction conflicts a. Pastoralism, transhumance and d. Conflict prevention and resolution migration Recommendations b. Challenges facing pastoralists Loss of pasture land and blockage of Chapter 4: THE ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF transhumance routes MAURITANIA p.49-57 Political (under-)representation and Introduction passivity a. Pastoralism and transhumance in Climate change and adaptation Mauritania Veterinary services b. Challenges facing pastoralists Education Water scarcity c. Security challenges and the causes and Shortages of pasture and animal feed in the drivers of conflict dry season Farmer-herder relations Challenges relating to cross-border Cattle rustling transhumance: The spread of terrorism to Burkina Faso Mauritania-Mali d. Conflict prevention and resolution Pastoralists and forest guards in Mali Recommendations Mauritania-Senegal c. Security challenges and the causes and Chapter 2: THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA p.31- drivers of conflict 38 The terrorist threat Introduction Armed robbery a. -

PRADD II Guinea Impact Evaluation Design Report

EVALUATION, RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATION (ERC) Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development Project II (PRADD II) Impact Evaluation Design Report AUGUST 2014 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Cloudburst Consulting Group, Inc. for the Evaluation, Research, and Communication (ERC) Task Order under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights (STARR) IQC. Written and prepared by Heather Huntington, Michael McGovern, and Darrin Christensen. Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development, USAID Contract Number AID- OAA-TO-13-00019, Evaluation, Research and Communication (ERC) Task Order under Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights (STARR) IQC No. AID-OAA-I-12-00030. Implemented by: Cloudburst Consulting Group, Inc. 8400 Corporate Drive, Suite 550 Landover, MD 20785-2238 EVALUATION, RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATION (ERC) Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development Project II (PRADD II) Impact Evaluation Design Report AUGUST 2014 DISCLAIMER The authors' views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS 36T36TCONTENTS36T36T ............................................................................................................................ 4 36T36TACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS36T36T ..................................................................................... 5 36T36T1.0 INTRODUCTION36T36T .............................................................................................................. -

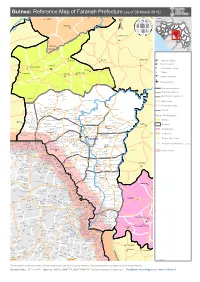

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (As of 05 March 2015)

Guinea: Reference Map of Faranah Prefecture (as of 05 March 2015) Kalinko SENEGAL MALI GUINEA Sélouma BISSAU GUINEA Komola Koura COTE D'IVOIRE SIERRA LEONE Dialakoro Kankama LIBERIA Sisséla Sanguiana Bissikirima Regional Capital District Capital Dabola Arfamoussayah Sub District Capital Banko Kounendou Village Dogomet N'demba Unpaved runway Paved runway Region boundaries Koulambo District boundaries Morigbeya Dar Es Salam Daro Gada Walan Sub District boundaries Kindoyé DIGUILA CENTRE Fabouya TOUMANIA CENTRE Boubouya Main roads Yombo Nialen Moria Dansoya Secondary roads NIENOUYA CENTRE Teliayaga Doukou Passaya Souriya Mansira Moribaya KONDEBOU KASSA BOUNA CENTRE Tambaya Rivers Foya Gadha Mongoli Babakadia Hafia Gomboya BELEYA CENTRE SABERE KALIA Keema SOUNGBANYA CENTRE Balandou Beindougou SANSANKO CENTRE Sidakoro Gueagbely Gueafari Sokora District (Préfectures) Harounaya Miniandala Badhi Gnentin Oussouya Banire Wolofouga Lamiya Gueagbely Mameyire SANSAMBOU CENTRE BIRISSA CENTRE NGUENEYA CENTRE NIAKO CENTRE Koumandi Koura Dabola Wassakaria Kobalen Bingal Dansoya Tomata Konkofaya Heredou Marela karimbou Sansamba Bouran SOLOYA CENTRE Kolmatamba KOUMANDI KORO Sanamoussaya MILIDALA CENTRE Banfele Labatara Gninantamba BONTALA Koura Sambouya DIANA CENTRE Sansando Faranah Wossekalia FRIGUIA CENTRE MAGNA Halossagoya KALIA CENTRE I KOMBONYA Ballayany Herewa Alia Filly Fore Sakoromaya SOLONYEREYA Khamaya Bindou Dansaya Koutamodiya Salia Kamako Kissidougou Goulouya Fantoumaniya Nerekoro SEREKORO CENTRE Guidonya Kombonyady Wassambala Balankhamba Kabaya -

The Use of a Roving Creel Survey to Monitor Exploited Coastal Fish Species in the Goukamma Marine Protected Area, South Africa

The use of a Roving Creel Survey to monitor exploited coastal fish species in the Goukamma Marine Protected Area, South Africa by Carika Sylvia van Zyl A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Technoligae, Nature Conservation Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University 2011 i I, Carika Sylvia van Zyl (s208027504) hereby declare that the work in this document is my own. ii Abstract A fishery-dependant monitoring method of the recreational shore-based fishery was undertaken in the Goukamma Marine Protected Area (MPA) on the south coast of South Africa for a period of 17 months. The method used was a roving creel survey (RCS), with dates, times and starting locations chosen by stratified random sampling. The MPA was divided into two sections, Buffalo Bay and Groenvlei, and all anglers encountered were interviewed. Catch and effort data were collected and catch per unit effort (CPUE) was calculated from this. The spatial distribution of anglers was also mapped. A generalized linear model (GLM) was fitted to the effort data to determine the effects of month and day type on the variability of effort in each section. Fitted values showed that effort was significantly higher on weekends than on week days, in both sections. A total average of 3662 anglers fishing 21 428 hours annually is estimated within the reserve with a mean trip length of 5.85 hours. Angler numbers were higher per unit coastline length in Buffalo Bay than Groenvlei, but fishing effort (angler hours) was higher in Groenvlei. Density distributions showed that anglers were clumped in easily accessible areas and that they favored rocky areas and mixed shores over sandy shores. -

Omvg Energy Project Countries

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : OMVG ENERGY PROJECT COUNTRIES : MULTINATIONAL GAMBIA - GUINEA- GUINEA BISSAU - SENEGAL SUMMARY OF ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Team Members: Mr. A.B. DIALLO, Chief Energy Engineer, ONEC.1 Mr. P. DJAIGBE, Principal Financial Analyst, ONEC.1/SNFO Mr. K. HASSAMAL, Economist, ONEC.1 Mrs. S.MAHIEU, Socio-Economist, ONEC.1 Mrs. S.MAIGA, Procurement Officer, ORPF.1/SNFO Mr. O. OUATTARA, Financial Management Expert, ORPF.2/SNFO Mr. A.AYASI SALAWOU, Legal Consultant, GECL.1 Project Team Mr. M.L. KINANE, Principal Environmentalist ONEC.3 Mr. S. BAIOD, Environmentalist, ONEC.3 Mr. H.P. SANON, Socio-Economist, ONEC.3 Sector Director: Mr. A.RUGUMBA, Director, ONEC Regional Director: Mr. J.K. LITSE, Acting Director, ORWA Division Manager: Mr. A.ZAKOU, Division Manager, ONEC.1, 1 OMVG ENERGY PROJECT Summary of ESIA Project Name : OMVG ENERGY PROJECT Country : MULTINATIONAL GAMBIA - GUINEA- GUINEA BISSAU - SENEGAL Project Ref. Number : PZ1-FAO-018 Department : ONEC Division: ONEC 1 1. INTRODUCTION This paper is the summary of the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) of the OMVG Project, which was prepared in July 2014. This summary was drafted in accordance with the environmental requirements of the four OMVG countries and the African Development Bank’s Integrated Safeguards System for Category 1 projects. It starts with a presentation of the project description and rationale, followed by the legal and institutional frameworks of the four countries. Next, a description of the main environmental conditions of the project is presented along with project options which are compared in terms of technical, economic and social feasibility.