Journal Paper Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Dylan Rose

TheULTIMATE ATOLL A Saltwater Utopia for the Adventuresome Angler by Dylan Rose he moment I set foot on Christmas Island my life was changed forever. My first visit was a metaphorical abstraction of the island’s vibe, culture, warmth and relaxed pace. As I stepped off of the big Fiji Airways 737 onto the tarmac I noticed from Tbehind the airport fence a small gathering of villagers quietly watching us deplane. Some of the island’s sun-kissed, bronzed-faced children were standing behind the chain link fence, smiling and waving excitedly. I Dylan Rose tracks a GT that turned to look behind me expecting to see a familiar party waving back, was spotted from the boat. but I soon realized their brilliant white smiles were actually for me and my Photo: Brian Gies intrepid gang of arriving fly anglers. PAGE 1 The ULTIMATE ATOLL Of all the places I’ve traveled, the feeling of being truly welcome in a the Pacific Ocean. Captain Cook landed on the island on Christmas Eve in foreign land is the strongest at Christmas Island. It’s the attribute about the 1777 and I can only imagine what a great holiday it might have been if he had place that connects me most to it. It’s baffling to me how a locale so far packed an 8-weight and a few Gotchas. away and different from anything I know can somehow still feel so much Blasted by high altitude, British H-bomb testing in the late 1950s and like home. From the giddy bouncing children swimming in the boat harbor again by the United States in the 1960s, Christmas Island and its magnificent to the villagers tending their chores; to the guides and their families, the lodge population of seabirds got a front row view of the inception of the atomic age. -

A Mortal Antipathy

A MORTAL ANTIPATHY Oliver Wendell Holmes A MORTAL ANTIPATHY Table of Contents A MORTAL ANTIPATHY......................................................................................................................................1 Oliver Wendell Holmes.................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 FIRST OPENING OF THE NEW PORTFOLIO.......................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................2 I. GETTING READY..................................................................................................................................14 II. THE BOAT−RACE................................................................................................................................19 III. THE WHITE CANOE...........................................................................................................................22 IV.................................................................................................................................................................24 V. THE ENIGMA STUDIED......................................................................................................................29 -

Polynesian Origins and Migrations

46 POLYNESIAN CULTURE HISTORY From what continent they originally emigrated, and by what steps they have spread through so vast a space, those who are curious in disquisitions of this nature, may perhaps not find it very difficult to conjecture. It has been already observed, that they bear strong marks of affinity to some of the Indian tribes, that inhabit the Ladrones and Caroline Islands: and the same affinity may again be traced amongst the Battas and the Malays. When these events happened, is not so easy to ascertain; it was probably not very lately, as they are extremely populous, and have no tradition of their own origin, but what is perfectly fabulous; whilst, on the other hand, the unadulterated state of their general language, and the simplicity which still prevails in their customs and manners, seem to indicate, that it could not have been at any very distant period (Vol, 3, p. 125). Also considered in the journals is the possibility of multiple sources for the vast Polynesian culture complex, but the conclusion is offered that a common origin was more likely. The discussion of this point fore shadows later anthropological arguments of diffusion versus independent invention to account for similar culture traits: Possibly, however, the presumption, arising from this resemblance, that all these islands were peopled by the same nation, or tribe, may be resisted, under the plausible pretence, that customs very similar prevail amongst very distant people, without inferring any other common source, besides the general principles of human nature, the same in all ages, and every part of the globe. -

The Outriggers of Indonesian Canoes. Author(S): A

The Outriggers of Indonesian Canoes. Author(s): A. C. Haddon Source: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 50 (Jan. - Jun., 1920), pp. 69-134 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2843375 . Accessed: 24/06/2014 21:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 195.78.108.81 on Tue, 24 Jun 2014 21:31:00 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 69 THE OUTRIGGERS OF INDONESIAN CANOES. By A. C. HADDON. CONTENTS. PAGE Material ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 70 Terminology ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. 72 Double Canoes ... ... ... ... .. ... ... ... ... ... 77 The Distribution of Single and Double Outriggers ..., ... ... ... ... ... 78 The Number of the Outrigger-Booms ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 79 The Attachment of the-Booms to the Hull ... ... ... ... 82 The Float .. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 83 The Attachmentsbetween the Booms and the Float and theirDistribution A.-Direct:- 1. Inserted ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 83, 123 2. Lashed ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 83, 124 3. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Archaeology Sailing the Monsoon Winds in Miniature: Model boats as evidence for boat building technologies, cultures and collecting by Charlotte Dixon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2018 ABSTRACT UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Archaeology Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SAILING THE MONSOON WINDS IN MINIATURE: MODEL BOATS AS EVIDENCE FOR BOAT BUILDING TECHNOLOGIES, CULTURES AND COLLECTING Charlotte Lucy Dixon Models of non-European boats are commonly found in museum collections in the UK and throughout the world. These objects are considerably understudied, rarely used in museum displays and at risk of disposal. In addition, there are several gaps in current understanding of traditional watercraft from the Indian Ocean, the region spanning from East Africa through to Western Australia. -

Boat Data Codes As of March 31, 2021 Boat Data Codes Table of Contents

Boat Data Codes As of March 31, 2021 Boat Data Codes Table of Contents 1 Outer Boat Hull Material (HUL) Field Codes 2 Propulsion (PRO) Field Codes 3 Canadian Vehicle Index Propulsion (PRO) Field Codes 4 Boat Make Field Codes 4.1 Boat Make and Boat Brand (BMA) Introduction 4.2 Boat Make (BMA) Field Codes 4.3 Boat Parts Brand Name (BRA) Field Codes 5 Boat Type (BTY) Field Codes 6 Canadian Boat Type (TYP) Field Codes 7 Boat Color (BCO) Field Codes 8 Boat Hull Shape (HSP) Field Codes 9 Boat Category Part (CAT) Field Codes 10 Boat Engine Power or Displacement (EPD) Field Codes 1 - Outer Boat Hull Material (HUL) Field Codes The code from the list below that best describes the material of which the boat's outer hull is made should be entered in the HUL Field. Code Material 0T OTHER ML METAL (ALUMINUM,STEEL,ETC) PL PLASTIC (FIBERGLASS UNIGLAS,ETC.) WD WOOD (CEDAR,PLYWOOD,FIR,ETC.) March 31, 2021 2 2 - Propulsion (PRO) Field Codes INBOARD: Any boat with mechanical propulsion (engine or motor) mounted inside the boat as a permanent installation. OUTBOARD: Any boat with mechanical propulsion (engine or motor) NOT located within the hull as a permanent installation. Generally the engine or motor is mounted on the transom at the rear of the boat and is considered portable. Code Type of Propulsion 0B OUTBOARD IN INBOARD MP MANUAL (OARS PADDLES) S0 SAIL W/AUXILIARY OUTBOARD POWER SA SAIL ONLY SI SAIL W/AUXILIARY INBOARD POWER March 31, 2021 3 3 - Canadian Vehicle Index Propulsion (PRO) Field Codes The following list contains Canadian PRO Field codes that are for reference only. -

Evolution of Arts Values and Typical of Techincal Outrigger in Pangandaran

2nd International Conference on Humanities, Art and Philosophies (2nd ICHAP 2020) eISBN 978-967-2426-06-6 11th – 12th July 2020 EVOLUTION OF ARTS VALUES AND TYPICAL OF TECHINCAL OUTRIGGER IN PANGANDARAN Indra Gunara Rochyat Faculty Design and Creative Industry, Esa Unggul University (UEU), Indonesia, (E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: Outrigger is a balancing device on a boat that is usually used by fishermen in the south coast of Java that serves as a tool so as not to capsize and will maintain stability when hit by waves and wind. Until now the general view is that outriggers are only a part of a fishing boat, whereas outriggers are not only a secondary part of a fisherman's transportation equipment, but are an important point that makes outriggers able to provide certain characteristics to coastal communities. The problems that arise are about the shape and structure of outriggers that are different from those on other coasts and the question of values contained in outrigger artiness has never been raised by researchers is a matter that deserves attention. The use of scientific aesthetic approach, namely the modern aesthetic approach and traditional aesthetic approach in uncovering the problem of values, as well as the diachronic model approach in the history of outrigger to reveal the typical characteristics of outrigger techniques is considered sufficient to analyze and conclude it. The conclusions are that the outrigger on a boat at Pangandaran can be said to have differences in characteristics and characteristics of those on the other coast due to the results of intelligence and reasoning of the craftsmen of the boating in the basis on various factors they receive, thus providing creativity stimulation to outrigger craftsmen who are ultimately able to produce value and new concepts on typical outriggers in Pangandaran. -

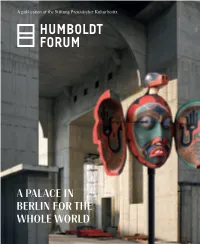

A Palace in Berlin for the Whole World

A publication of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz A PALACE IN BERLIN FOR THE WHOLE WORLD MF 1 Humboldt Forum Humboldt Forum HP The presentation in Dahlem still follows the nar- What connects Alaska and Berlin? TIME TO TALK rative of an ethnological museum – very static and offering little scope for change. In the Humboldt How to build a Buddhist cave in a museum? Forum we’ll be able to be much more flexible and to Where were icons invented? ABOUT CONTENT tell the stories from multiple perspectives, allowing the voices of the indigenous cultures from which the A Q&A session with Hermann Parzinger, objects came to be heard. And we will try to focus To find out all this and more, come more than in Dahlem on current issues like climate and visit the new cultural heart of Berlin change and migration. In fact, we’ll be dealing with President of the all the major issues that concern us today. 5. Last spring, the Federal Government Commis- Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz sioner for Culture appointed a trio as founding directors of the Humboldt Forum: yourself, the art historian Horst Bredekamp, and Neil MacGregor, 1. We’re standing in the shell of the Stadtschloss, former director of London’s British Museum, as the Berlin Palace. Where exactly are we? team leader. The press enthused wildly about the HERMANN PARZINGER In the foyer, near the main entrance choice of MacGregor and his acceptance of the directly under the cupola. The visitors’ routes through post. What makes him the right person? the building will all lead off from this vast hall. -

The Origins and Ethnological Significance of Indian Boat Designs

The Origins and Ethnological Significance Of Indian Boat Designs JAMES HORNELL Director of Fisheries, Madras Government Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Calcutta 1920 Re- issued by South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies, Trivandrum Indian Boat Designs 1 The Origins and Ethnological Significance Of Indian Boat Designs JAMES HORNELL Director of Fisheries, Madras Government Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal Calcutta 1920 Re- issued by South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies, Trivandrum 2 J. Hornell on THE ORIGINS AND ETHONOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF INDIAN BOAT DESIGNS Ist Print 1920 Re Issued September 2002 Re - Issued By South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies Karamana (P.O), Trivandrum - 695 002 Tel : (91) 471- 34 3711, 34 3178 Fax : (91) 471 - 34 2053 Email : [email protected] Website : http://www.siffs.org Design by SIFFS Computer Centre Printed at G.K. Enterprises, Ernakulam This work was first published in 1920. Every attempt has been made to trace the copyright for this work. The publishers would value any information from or about copyright owners for acknowledgement in future editions of this book. Indian Boat Designs 3 PREFACE (to this re-issue) Fishing in India has a great antiquity, but very little documentation exists of the technical aspects in any of our ancient or medieval records and literature. It is only in colonial times that substantial documentation emerges on fishermen and their occupation. The role of the Madras Fisheries Department is the most significant in this. Set up in 1907 under Sir Fredrick Nicholson, its remarkable work in fisheries documentation will put to shame all our post-colonial efforts. -

Earlywatercraft – a Global Perspective of Invention and Development

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289239067 Proposal of the Global Initiative: EarlyWatercraft – A global perspective of invention and development Book · January 2016 CITATIONS READS 0 6,788 1 author: Miran Erič Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage of Slovenia 44 PUBLICATIONS 87 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Visual language View project Underwater documentation methodology View project All content following this page was uploaded by Miran Erič on 06 September 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. GLOBAL INITIATIVE: Early Watercraft – A global perspective of invention and development Proposal of the Initiative (Edited by: Ronald Bockius and Miran Eriˇcwith Ambassadors) Vrhnika, Slovenia 19th - 23rd of April 2015 GLOBAL INITIATIVE: Early Watercraft – A global perspective of invention and development Figure 1: Symbolic meaning of the official EWA logotype Idria lace represent water net and connecting of all nation around the world Inner green round drawing representing our planet Earth Outer red round drawing represent the oldest and most important human invention Early Watercraft Initiative is the short name of the global initiative ”Early Watercraft - a global perspective of invention and development” Red colour of the name is the symbolic meaning of the oldest clay red pigment iron oxide used by humankind Early Watercraft – A global perspective of invention -

Words for Canoes: Continuity and Change in Oceanic Sailing Craft

WORDS FOR CANOES: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN OCEANIC SAILING CRAFT ANNE DI PIAZZA Aix-Marseille Université Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) Centre de recherche et de documentation sur l’Océanie (CREDO) Historically canoes are something of an enigma in the Pacific. They are extensively documented from the first contact period up to the present, but there is no widespread agreement pertaining to their design and technological innovations through time. Their few archaeological remains are not sufficiently informative, rendering such a topic challenging but, as developed below, historical linguistics can help to reconstruct Proto-Oceanic (POc), Proto-Central Pacific (PCP) and Proto-Polynesian (PPN) canoes. Pawley (2007: 26) has written: More than 20 terms for canoe parts and associated items are attributable to POc (Pawley and Pawley 1994). These include names for parts of a five-piece built-up hull, end pieces, projecting parts of the outrigger complex, platform, sail, boom of sail, steering oar, paddles, bailers, rollers for beaching and launching canoes, and anchors, indicating that POc speakers built substantial ocean-going outrigger canoes. Such lexical evidence supplements the paucity of archaeological data of pre-contact canoes but more importantly allows relative dating of technological innovations. By tracing the histories of cognates and/or semantic fields related to the canoe complex, we can learn a great deal about continuity and change in maritime history. This idea is not new. Geraghty (1994), Lynch (1994), Osmond (2003), Osmond et al. (2003), Pawley (2007) and Pawley and Pawley (1994) have used historical linguistics to reconstruct aspects of the canoe complex and the maritime environment. -

Whalewatcher 2020 • Vol

Journal of the American Cetacean Society WHALEWATCHER 2020 • VOL. 43 • NO. 1 BREAKING THE SURFACE WOMENOFCETOLOGY Humpback calf. Photo by Jo Marie Acebes. Editorial Pod ACS National Board of Directors LEAD EDITOR Read about our Board Members at Sabena Siddiqui acsonline.org ASSISTANT EDITORS PRESIDENT Diane Glim Uko Gorter Uko Gorter SECRETARY On the Cover Kelsey Stone Diane Glim The Caldwells recording PRODUCTION ARTIST TREASURER vocalizations of a Rose Freidin Ric Matthews bottlenose dolphin at Marineland of Florida. Shelby Kasberger, Conservation Chair Photo by: Marineland of Florida Joy Primrose Sabena Siddiqui, Student Chair AMERICAN CETACEAN SOCIETY Kelsey Stone, Social Media Manager P.O. Box 51691 Jayne Vanderhagen Pacific Grove, CA 93950 Bob Wilson acsonline.org ACS Team Members Kara Henderlight, Advocacy Chair 2 BREAKING THE SURFACE WOMEN OF CETOLOGY Letter from the President Uko Gorter ou may have noticed that this special We thought it was high time to look back I want to express my gratitude to our ACS issue of our Whalewatcher journal is and see how far women have come in the National Board Member, Sabena Siddiqui, not really about whales. Instead, it is field of cetology, or the study of whales. We who served as our lead Editor for this Yabout humans. Women, to be more precise. also wanted to hear from women scientists wonderful issue. Sabena has deftly guided who are working in the field today, or the process with immense patience and For anyone who has attended a marine recently retired. The results are essays from sensitivity. It is because of her efforts, mammal science conference recently, a wonderful mix of women from different while still navigating her own academic you would have immediately noticed the generations, backgrounds, and career work, that this unique special issue has multitude of women in attendance.