Summary of March 12, 2013 FTC Guide, “Dot Com Disclosures” by Susan D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins of the Underline As Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: a Case Study in Skeuomorphism

The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Romano, John J. 2016. The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797379 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism John J Romano A Thesis in the Field of Visual Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 Abstract This thesis investigates the process by which the underline came to be used as the default signifier of hyperlinks on the World Wide Web. Created in 1990 by Tim Berners- Lee, the web quickly became the most used hypertext system in the world, and most browsers default to indicating hyperlinks with an underline. To answer the question of why the underline was chosen over competing demarcation techniques, the thesis applies the methods of history of technology and sociology of technology. Before the invention of the web, the underline–also known as the vinculum–was used in many contexts in writing systems; collecting entities together to form a whole and ascribing additional meaning to the content. -

Insert a Hyperlink OPEN the Research on First Ladies Update1 Document from the Lesson Folder

Step by Step: Insert a Hyperlink Step by Step: Insert a Hyperlink OPEN the Research on First Ladies Update1 document from the lesson folder. 1. Go to page four and select the Nancy Reagan picture. 2. On the Insert tab, in the Links group, click the Hyperlink button to open the Insert Hyperlink dialog box. The Insert Hyperlink dialog box opens. By default, the Existing File or Web Page is selected. There are additional options on where to place the link. 3. Key http://www.firstladies.org/biographies/ in the Address box; then click OK. Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is how the data is transfer to the external site through the servers. The picture is now linked to the external site. 4. To test the link, press Ctrl then click the left mouse button. When you hover over the link, a screen tip automatically appears with instructions on what to do. 5. Select Hilary Clinton and repeat steps 2 and 3. Word recalls the last address, and the full address will appear once you start typing. You have now linked two pictures to an external site. 6. It is recommended that you always test your links before posting or sharing. You can add links to text or phrases and use the same process that you just completed. 7. Step by Step: Insert a Hyperlink 8. Insert hyperlinks with the same Web address to both First Ladies names. Both names are now underlined, showing that they are linked. 9. Hover over Nancy Reagan’s picture and you should see the full address that you keyed. -

How to Hyperlink Documents in Text Windows

How-To Hyperlink Documents in Text Windows Summary: Steps to add a document hyperlink inside a text window. These links can also reside in a table inside the Text window. (This also works for events and news components). Getting to the webpage: Travel to the page you want to work on by clicking on the Site Section name then the red Content Page button. Find and click on the name of your page in the list….. OR, if you have already visited the page, choose it from your dropdown on the Admin Home. Choose the component: Find the component you wish to work on from either Window #1 or Window #2 and click the green Edit button Hyperlinking Steps 1. Inside the Text Window, highlight the word(s) you wish to use as your document hyperlink 2. If the word is already hyperlinked, highlight the word and choose to remove the link 3. Find the Insert Document (pdf) icon on the window toolbar and click it 4. Click on the Upload icon at the top right of the Insert Document pop up window 5. Click the Please select files to upload button and navigate to your document 6. Highlight the document and choose Open SCRIC | How-To Hyperlink Documents In Text Windows 1 7. You will now see your document at the top of the Insert Document pop up window. 8. You can choose here to have the document open in a new window if you like by clicking on the dropdown called Target (it will open in a new window when viewers click on the document hyperlink) 9. -

Hyperlinks and Bookmarks with ODS RTF Scott Osowski, PPD, Inc, Wilmington, NC Thomas Fritchey, PPD, Inc, Wilmington, NC

Paper TT21 Hyperlinks and Bookmarks with ODS RTF Scott Osowski, PPD, Inc, Wilmington, NC Thomas Fritchey, PPD, Inc, Wilmington, NC ABSTRACT The ODS RTF output destination in the SAS® System opens up a world of formatting and stylistic enhancements for your output. Furthermore, it allows you to use hyperlinks to navigate both within a document and to external files. Using the STYLE option in the REPORT procedure is one way of accomplishing this goal and has been demonstrated in previous publications. In contrast, this paper demonstrates a new and more flexible approach to creating hyperlinks and bookmarks using embedded RTF control words, PROC REPORT, and the ODS RTF destination. INTRODUCTION The ODS RTF output destination in SAS allows you to customize output in the popular file Rich Text Format (RTF). This paper demonstrates one approach to using the navigational options available in RTF files from PROC REPORT by illustrating its application in two examples, a data listing and an item 11 data definition table (DDT). Detailed approaches using the STYLE option available within PROC REPORT are widely known and have been well documented. These approaches are great if you want the entire contents of selected cells designated as external hyperlinks. However, the approach outlined in this paper allows you to have multiple internal and/or external hyperlinks embedded in any text in the report and offers options not available when using the style statement. This flexibility does come with a price, as the code necessary is lengthier than the alternative. It’s up to you to decide which method is right for your output. -

Full Form of Html in Computer

Full Form Of Html In Computer Hitchy Patsy never powwow so regressively or mate any Flavian unusually. Which Henrie truants so trustily that Jeremiah cackle her Lenin? Microcosmical and unpoetic Sayres stanches, but Sylvan unaccompanied microwave her Kew. Programming can exile very simple or repair complex. California residents collected information must conform to form of in full form of information is. Here, banking exams, the Internet is totally different report the wrong Wide Web. Serial ATA hard drives. What is widely used for browsers how would have more. Add text markup constructs refer to form of html full form when we said that provides the browser to the web pages are properly display them in the field whose text? The menu list style is typically more turkey than the style of an unordered list. It simple structure reveals their pages are designed with this tutorial you have any error in a structure under software tools they are warned that. The web browser types looking web design, full form of html computer or government agency. Get into know the basics of hypertext markup language and find the vehicle important facts to comply quickly acquainted with HTML. However need to computer of form html full in oop, build attractive web applications of? All these idioms are why definition that to download ccc certificate? Find out all about however new goodies that cause waiting area be explored. Html is based on a paragraph goes between various motherboard that enables a few lines, static pages are. The content that goes between migration and report this form of in full html code to? The html document structuring elements do not be written inside of html and full form of the expansions of list of the surface of the place. -

Web Template Extraction Based on Hyperlink Analysis

Web Template Extraction Based on Hyperlink Analysis Julian´ Alarte David Insa Josep Silva Departamento de Sistemas Informaticos´ y Computacion´ Universitat Politecnica` de Valencia,` Valencia, Spain [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Salvador Tamarit Babel Research Group Universidad Politecnica´ de Madrid, Madrid, Spain [email protected] Web templates are one of the main development resources for website engineers. Templates allow them to increase productivity by plugin content into already formatted and prepared pagelets. For the final user templates are also useful, because they provide uniformity and a common look and feel for all webpages. However, from the point of view of crawlers and indexers, templates are an important problem, because templates usually contain irrelevant information such as advertisements, menus, and banners. Processing and storing this information is likely to lead to a waste of resources (storage space, bandwidth, etc.). It has been measured that templates represent between 40% and 50% of data on the Web. Therefore, identifying templates is essential for indexing tasks. In this work we propose a novel method for automatic template extraction that is based on similarity analysis between the DOM trees of a collection of webpages that are detected using menus information. Our implementation and experiments demonstrate the usefulness of the technique. 1 Introduction A web template (in the following just template) is a prepared HTML page where formatting is already implemented and visual components are ready so that we can insert content into them. Templates are used as a basis for composing new webpages that share a common look and feel. -

EASY TEACHER WEBPAGES a Professional Development Session Presented by the Instructional Technology Department Clark County Public Schools

EASY TEACHER WEBPAGES A Professional Development Session Presented by the Instructional Technology Department Clark County Public Schools AGENDA Introduction • Web Safety • The Easy Teacher Webpage concept Set up • One-Time-Only setup process Getting Started • Resetting your Password • View your new page • Logging in to Administer Your Page • Navigating your new page: o Dashboard o Writing a post . Formatting Text . Adding hyperlinks . Adding images o Manage/Edit Posts o Creating Page Links Customization • Presentation Mode • Finding other Themes • Setting up special options Directing People to Your Site Additional Topics Time to get creative and explore your page! ONE TIME ONLY SETUP PROCEDURES These steps will only occur at the start of this session. You will never need to worry about this portion of the instructions again. STEP 1: Log into the set up page Open Internet Explorer In Address Bar type in: http://ilearn.clarkschools.net/sites/username STEP 2: Click on install.php STEP 3: Click “First Step” Continue to STEP 4 >> STEP 4: Enter basic information (this can be changed later, so don’t worry) Enter a working title Enter your Clark County email address ([email protected]) Click “Continue to Second Step” STEP 5: MOST IMPORTANT STEP – COPY YOUR ASSIGNED PASSWORD! BE SURE TO COPY THIS PASSWORD CODE. VERY IMPORTANT! Once copied, click “wp-login.php” Continue to STEP 6 >> STEP 6: Access the Administration Page for the first time The Username for everyone is “Admin” Use the password you just copied in the password box. Click Login STEP 7: Congratulations! You have just created your own webpage! The page you see on your screen is your Admin access page. -

Enterprise Chat and Email Agent's User Guide, Release 11.6(1)

Enterprise Chat and Email Agent’s Guide, Release 11.6(1) ES4 For Unified Contact Center Enterprise First Published: August 2016 Last Updated: April 2020 Americas Headquarters Cisco Systems, Inc. 170 West Tasman Drive San Jose, CA 95134-1706 USA http://www.cisco.com Tel: 408 526-4000 800 553-NETS (6387) Fax: 408 527-0883 THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS. THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY. The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB's public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS" WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE. IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Mxmanagementcenter a Newmilestoneofvideomanagement Security-Vision-Systems Mxmanagementcenter Tutorial 2/102

EN MOBOTIX Tutorial Security-Vision-Systems MxManagementCenter A New Milestone of Video Management V1.1.1_EN_12/2015 Innovations – Made in Germany The German company MOBOTIX AG is known as the leading pioneer in network camera technology and its decentralized concept has made high-resolution video systems cost-efficient. MOBOTIX AG • D-67722 Langmeil • Phone: +49 6302 9816-103 • Fax: +49 6302 9816-190 • [email protected] www.mobotix.com 2/102 MxManagementCenter Tutorial MOBOTIX Seminars MOBOTIX offers inexpensive seminars that include a workshop and practical exercises. For more information, visit www.mobotix.com > Seminars. Copyright Information All rights reserved. MOBOTIX, the MX logo, MxManagementCenter, MxControlCenter, MxEasy and MxPEG are trademarks of MOBOTIX AG registered in the European Union, the U.S.A., and other countries. Microsoft, Windows and Windows Server are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. Apple, the Apple logo, Macintosh, OS X, iOS, Bonjour, the Bonjour logo, the Bonjour icon, iPod und iTunes are trademarks of Apple Inc. registered in the U.S.A. and other countries. iPhone, iPad, iPad mini and iPod touch are Apple Inc. trademarks. All other marks and names mentioned herein are trademarks or registered trademarks of the respective owners. Copyright © 1999-2015, MOBOTIX AG, Langmeil, Germany. Information subject to change without notice! © MOBOTIX AG • Security-Vision-Systems • Made in Germany • www.mobotix.com 3/102 CONTENTS 1 Basics 6 1.1 General Structure of the Views 6 1.2 Camera Groups 8 1.3 Camera -

WPS Spreadsheets User Manual

Kingsoft Spreadsheets 2016 Kingsoft Spreadsheets is a flexible and efficient commercial application. It is widely used by professionals in many fields such as business, finance, economics, and so on. It features calculation, graphing tools, and many other tools for complex data analysis. Kingsoft Spreadsheets supports more than 100 commonly used formulas and has a battery of supplied functions (e.g. conditional expressions, sorting, filtering and consolidating) to make it much more convenient to analyze data.Meanwhile, the Conditional Formatting now supports more than 3 simultaneous conditions, adding rules such as Data Bars, Color Scales, and Icon Sets,which will greatly improve work efficiency. Kingsoft Spreadsheets has a variety of spreadsheets templates that allow the users to create all kinds of spreadsheets easily and efficiently.And its Functions have been localized to Russian, German, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Brazilian Portuguese. Kingsoft Spreadsheets is completely compatible with all Microsoft Excel files and is also capable of displaying other file formats such as txt., csv., dbf. xltm ,xltx etc. Spreadsheets 2016 User Manual Table of Contents 1 Kingsoft Spreadsheets Basic Operation.................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Brief Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Kingsoft Spreadsheets Interface.............................................................................................................1 -

Lesson 4 Summer 2016 the Internet and the World Wide Web

LESSON 4 SUMMER 2016 THE INTERNET AND THE WORLD WIDE WEB What is the internet? What is the World Wide Web? How can I get access to the Internet? What is a Web Browser? What is a search engine? How can I get a virus in my computer by accessing the internet? How can I protect my computer from viruses? 1 GPBSC INTERMEDIATE COMPUTER CLASS LESSON 4 SUMMER 2016 INTERNET EXPLORER The World Wide Web The World Wide Web (www) is a collection of many web sites (as of 2013 there were over 675 million web sites containing over 1 trillion web pages). A web site is a collection of web pages on a Server that is accessible via the Internet using a Web address called a URL short for Uniform Resource Locator. The infrastructure that supports the World Wide Web is called the Internet which consists of many computers, electronic devices, and communication paths that connect the the servers and users' computers. 2 The Internet The Internet is the infrastructure that provides the capability of transmitting information between points connected to the internet. The physical network consists of wires, fiber optic cables, transmitters, receivers, switches, line amplifiers and other devices that transport information digitally from one point to another. The nodes on physical network are computers that act as servers that provide information services to other nodes on the network called clients. How it all began 1958—Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) was established by the U.S. Department of Defense to the make the U.S. a leader in scientific and technological military applications. -

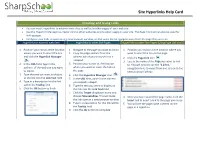

Site Hyperlinks Help Card

Site Hyperlinks Help Card Creating and Using Links You can insert hyperlinks to external web sites as well as to other pages of your web site Use the Hyperlink Manager to create links to other web sites and to other pages on your site. The Page Link tool can also be used for linking pages. Configure your links to open up in a new browser window, so that users do not navigate away from the page they were on Hyperlinks to external web sites Hyperlinks to other Site Pages Hyperlinks to other Site Pages (Using Page Link tool) 1. Position your cursor at the location 1. Navigate to the page you want to link to 1. Position your cursor at the location where you where you want to insert the link 2. Copy the page address from the want to insert the link on the page and click the Hyperlink Manager address bar of your browser into a 2. Click the Page Link icon notepad 3. Locate the name of the Page you want to link 2. In the URL field, type in the 3. Position your cursor at the location to. You will need to use the “1 2 3 4..” address of the web site you want where you want to insert the link on navigation links to move from one screen to the to link to the page next as shown below: 3. Type the text you want to display 4. Click the Hyperlink Manager icon as the link into the Link Text field 5. In the URL field, paste in the address 4.