Miller Umbc 0434M 11891.Pdf (2.594Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook'

"We Are Bound to Tradition Yet Part of That Tradition Is Change": The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook' Ilana Harlow Indiana University The traditional Jewish liturgy in its diverse manifestations is an imposing artistic structure. But unlike a painting or a symphony it is not the work of one artist or even the product of one period. It is more like a medieval cathedral, in the construction of which many generations had a share and in the ultimate completion of which the traces of diverse tastes and styles may be detected. (Petuchowski 1985:312) This essay explores the dynamics between tradition and innovation, authority and authenticity through a study of a recently edited Jewish prayerbook-a contemporary development in a tradition which can be traced over a one-thousand year period. The many editions of the Jewish prayerbook, or siddur, that have been compiled over the centuries chronicle the contributions specific individuals and communities made to the tradition-informed by the particular fashions and events of their times as well as by extant traditions. The process is well-captured in liturgist Jakob Petuchowski's 'cathedral simile' above-an image which could be applied equally well to many traditions but is most evident in written ones. An examination of a continuously emergent written tradition, such as the siddur, can help highlight kindred processes involved in the non-documented development of oral and behavioral traditions. Presented below are the editorial decisions of a contemporary prayerbook editor, Rabbi Jules Harlow, as a case study of the kinds of issues involved when individuals assume responsibility for the ongoing conserva- tion and construction of traditions for their communities. -

International Trends

Wedding Cultures INTERNATIONAL TRENDS - Jean Oosthuzien Weddings – All Around the World INTERNATIONAL WEDDING TRENDS Agenda Recap of Christian Weddings Other Wedding Customs Chinese Weddings Pakistan Weddings German Weddings Planning a Wedding Creating a Budget Case study of the budget How do we go about a themed Christian wedding ? Let’s take… John and Jane’s wedding THE PARK HYATT, DEIRA, DUBAI 14TH FEBRUARY 2016 2.30 PM Themes Valentine’s Day Hearts Colour Schemes Reds Creams Whites * Flowers and Colours Red Roses for bride’s bouquet. Red Rose corsage for groom’s lapel. White Rose bouquets for the bridesmaids. Bridesmaids will wear red dresses. Groom will wear a red tie. Bridal Wear – Vintage Parisienne Glamour. Food and Drink French champagne with strawberries for drinks reception. Dinner Menu: Duck Foie Gras, peach chutney, brioche – Panfried Beef Tenderloin – Grand crus chocolate mille feuille – tea, coffee and petit fours. French macaroon wedding cake The top table will seat 10 people: The Bride and Groom, Basic Floor Plan Bride’s Mother and Father, Groom’s Mother and Father, 2 Bridesmaids and 2 Groomsmen. Top Table Each round table will seat 10 guests. The central round table will display the cake and will be moved after cutting of the cake to make way for a central dance floor. The band will be positioned near the top table in the evening. * Event Flow Summary N.b. civil ceremony has already taken place in prior to this celebration so the couple are legally married. 1.45 Groom arrives at Marina Garden for ceremony with his Groomsmen and parents. -

Jewish Pilgrims to Palestine

Palestine Exploration Quarterly ISSN: 0031-0328 (Print) 1743-1301 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ypeq20 Jewish Pilgrims to Palestine Marcus N. Adler To cite this article: Marcus N. Adler (1894) Jewish Pilgrims to Palestine, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 26:4, 288-300, DOI: 10.1179/peq.1894.26.4.288 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/peq.1894.26.4.288 Published online: 20 Nov 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 6 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ypeq20 Download by: [Universite Laval] Date: 06 May 2016, At: 16:50 288 JEvVISH PILGRIMS TO PALESTINE. JEWISH, PILGRIMS TO PALESTINE. By MARCUS N. ADLER, M.A. IN response to th~ desire expressed by the Committee. of the Palestine Exploration Fund, I have much pleasure in furnishing a short account of the works of the early Jewish travellers in the East, and I propose also to give extracts from some of their writings which have reference to Palestine. Even prior to the destruction of the Second Temple, Jews were settled in most of the known countries of antiquity, and kept up com- munication with the land of their fathers. Passages from the Talmud prove that the sage Rabbi Akiba, who led the insurrection of the Jews against Hadrian, had visited many countries, notably Italy, Gaul, .Africa, Asia Minor, Persia, and Arabia. The Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds, the Midrashim and other Jewish writings up to the ninth century, contain innumerable references to the geography of Palestine. -

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death Remi Jedwab and Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama⇤ April 16, 2018 Abstract We study the Black Death pogroms to shed light on the factors determining when a minority group will face persecution. In theory, negative shocks increase the likelihood that minorities are persecuted. But, as shocks become more severe, the persecution probability decreases if there are economic complementarities between majority and minority groups. The effects of shocks on persecutions are thus ambiguous. We compile city-level data on Black Death mortality and Jewish persecutions. At an aggregate level, scapegoating increases the probability of a persecution. However, cities which experienced higher plague mortality rates were less likely to persecute. Furthermore, for a given mortality shock, persecutions were less likely in cities where Jews played an important economic role and more likely in cities where people were more inclined to believe conspiracy theories that blamed the Jews for the plague. Our results have contemporary relevance given interest in the impact of economic, environmental and epidemiological shocks on conflict. JEL Codes: D74; J15; D84; N33; N43; O1; R1 Keywords: Economics of Mass Killings; Inter-Group Conflict; Minorities; Persecutions; Scapegoating; Biases; Conspiracy Theories; Complementarities; Pandemics; Cities ⇤Corresponding author: Remi Jedwab: Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, George Washington University, [email protected]. Mark Koyama: Associate -

Aus Dem Leben Des Missionars Johannes, Heinrich, Christoph Lilje

JOHANN HEINRICH CHRISTOPH LILJE * 15.09.1833 † 23.09.1920 Married on 25.09.1871 ANNA CAROLINE LILJE (BECKRÖGE) * 09.06.1847 † 10.09.1935 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................ 2 FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 FOREWORD TO THE SECOND EDITION .............................................................................................................. 6 SECTION I: THE MISSIONARY JOHANN HEINRICH CHRISTOPH LILJE .................................................................... 7 1 The greater Lilje family: Lylye, Lillie, Lilie, Lilje, Lilien, Lilye, Lillige ....................................................... 7 1.1 Steinhorst .................................................................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Lüsche .......................................................................................................................................................... 11 1.3 Allersehl ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 1.4 Gerdau ......................................................................................................................................................... 13 2 -

TOPICS in Perek

CONTENTS Techeiles Revisited Rabbi Berel Wein PAGES 2-4 Principles Regarding Tying Tzitzis with Techeiles Collected Sources PAGES 5-7 Kala Ilan Rabbi Ari Zivotofsky PAGES 8-9 TOPICS IN Dyeing Techeiles Perek Dr. Baruch Sterman PAGES 10-11 Maareh Sheni in Dyeing Techeiles PAGES 12-13 HaTecheiles Rav Achai’s Dilemna DAF YOMI • MENACHOS PEREK 4 PAGES 12-13 The Coins of Techeiles Dr. Ari Greenspan PAGE 15 Techeiles Revisited “Color is an emotional Rabbi Berel Wein experience. Techeiles ne of the enduring mysteries of Jewish life following the exile of the is the emotional Jews from the Land of Israel was the disappearance of the string of Otecheiles in the tzitzis garment that Jews wore. Techeiles was known reminder of the bond to be of a blue color while the other strings of the tzitzis were white in color. Not only did Jews stop wearing techeiles but they apparently even forgot how between ourselves and it was once manufactured. The Talmud identified techeiles as being produced Hashem and how we from the “blood” of a sea creature called the chilazon. And though the Talmud did specify certain traits and identifying characteristics belonging to the get closer to Hashem chilazon, the description was never specific enough for later generations of Jews to unequivocally determine which sea creature was in fact the chilazon. with Ahavas Hashem, It was known that the chilazon was harvested in abundance along the northern coast of the Land of Israel from Haifa to south of Tyre in Lebanon (Shabbos the love of Hashem, 26a). Though techeiles itself disappeared from Jewish life as part of the damage the love of Torah and of exile, the subject of techeiles continued to be discussed in the great halachic works of all ages. -

University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich

Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. Winterthurerstr. 190 CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007 Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. THE BOOK OF JUBILEES: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY FROM THE FIRST GERMAN TRANSLATION OF 1850 TO THE ENOCH SEMINAR OF 2007 ISAAC W. OLIVER , University of Michigan VERONIKA BACHMANN , University of Zurich The following annotated bibliography provides summaries of the most influential scholarly works dedicated to the Book of Jubilees written between 1850 and 2006. * The year 1850 opens the period of modern research on Jubilees thanks to Dillmann’s translation of the Ethiopic text of Jubilees into German; the Enoch Seminar of 2007 represents the largest gathering of international scholars on the document in modern times. -

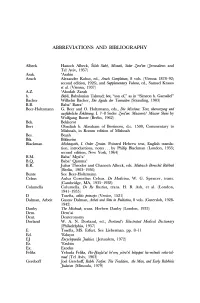

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Missouri Folklore Society Journal

Missouri Folklore Society Journal Special Issue: Songs and Ballads Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Cover illustration: Anonymous 19th-century woodcut used by designer Mia Tea for the cover of a CD titled Folk Songs & Ballads by Mark T. Permission for MFS to use a modified version of the image for the cover of this journal was granted by Circle of Sound Folk and Community Music Projects. The Mia Tea version of the woodcut is available at http://www.circleofsound.co.uk; acc. 6/6/15. Missouri Folklore Society Journal Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Special Issue Editor Lyn Wolz University of Kansas Assistant Editor Elizabeth Freise University of Kansas General Editors Dr. Jim Vandergriff (Ret.) Dr. Donna Jurich University of Arizona Review Editor Dr. Jim Vandergriff Missouri Folklore Society P. O. Box 1757 Columbia, MO 65205 This issue of the Missouri Folklore Society Journal was published by Naciketas Press, 715 E. McPherson, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 ISSN: 0731-2946; ISBN: 978-1-936135-17-2 (1-936135-17-5) The Missouri Folklore Society Journal is indexed in: The Hathi Trust Digital Library Vols. 4-24, 26; 1982-2002, 2004 Essentially acts as an online keyword indexing tool; only allows users to search by keyword and only within one year of the journal at a time. The result is a list of page numbers where the search words appear. No abstracts or full-text incl. (Available free at http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Search/Advanced). The MLA International Bibliography Vols. 1-26, 1979-2004 Searchable by keyword, author, and journal title. The result is a list of article citations; it does not include abstracts or full-text. -

The Man-Made Holiday Rabbi Aaron Kraft Wexner Kollel Elyon

The Man-Made Holiday Rabbi Aaron Kraft Wexner Kollel Elyon Purim Then and Now The verses towards the end of Megillat Esther leave us with an ambiguous understanding of Purim’s status. They repeat the general themes and mitzvot of the day numerous times, but with regards to whether Purim is actually a Yom Tov we find ourselves perplexed. The confusion lies in the comparison between the first Purim celebrated by the victorious Jewish nation and the Purim established by Mordechai for the future. After describing the miraculous events of the 13th and 14th of Adar, the Megillah records the reaction of the Jewish people: על כן היהודים הפרזים הישבים בערי -Therefore do the Jews of the villages, that dwell in the un הפרזות עשים את יום ארבעה עשר לחדש walled towns, make the fourteenth day of the month Adar אדר שמחה ומשתה ויום טוב ומשלוח מנות a day of gladness and feasting, and a Yom Tov,, and of איש לרעהו: .sending portions one to another אסתר ט:יט Esther 9:19 Just three verses later, the Megillah reports Mordechai’s enactment of Purim as a day of annual celebration: כימים אשר נחו בהם היהודים The days wherein the Jews had rest from their enemies, and the מאויביהם והחדש אשר נהפך להם ,month which was turned unto them from sorrow to gladness מיגון לשמחה ומאבל ליום טוב לעשות and from mourning into a good day; that they should make אותם ימי משתה ושמחה ומשלוח them days of feasting and gladness, and of sending portions מנות איש לרעהו ומתנות לאביונים: one to another, and gifts to the poor אסתר ט:כב Esther 9:22 In other words, the pesukim deem the initial celebration a Yom Tov whereas Mordechai drops this formulation in his decree for the future. -

Reasonable Man’

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2019 The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ Johnny Sakr The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Law Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Sakr, J. (2019). The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ (Master of Philosophy (School of Law)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/215 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Conjecture from the Universality of Objectivity in Jurisprudential Thought: The Universal Presence of a ‘Reasonable Man’ By Johnny Michael Sakr Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy University of Notre Dame Australia School of Law February 2019 SYNOPSIS This thesis proposes that all legal systems use objective standards as an integral part of their conceptual foundation. To demonstrate this point, this thesis will show that Jewish law, ancient Athenian law, Roman law and canon law use an objective standard like English common law’s ‘reasonable person’ to judge human behaviour. -

Act I, Signature V - (1)

When the audience is known to be secretly skeptical of the reality that is being impressed upon them, we have been ready to appreciate their tendency to pounce upon trifling flaws as a sign that the whole show is false [Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self (New York: Anchor Press, 1959), p. 51]. I - v - Give Me Seventeen Dollars for This Hat. Taxed by the forces besetting Damascus, the Sultan accedes to familial intrigue. The noted medical talk show host, Mr. Ng, surges to stage a live remote into the 13 th century. The various tools at his command are listed. The participants gather: the Idiopath of Jerusalem, the chorus, the Emperor Frederick II, al-Kamil, Sultan of Egypt, and the Rabbi Ben ‘tov Shapiro. A debate over the independence of scientific thought, in which the Idiopath disputes the Frankish titles in Palestine, ensues. Al-Kamil also cites numerous correspondences contesting these claims. ~ page 63 ~ People showing up for a diagnosis of a sample of their urine to the physician Constantine the African.* Constantine Act I, Signature v - (1) Latin Constantinus Africanus Born c. 1020, Carthage or Sicily Died 1087, monastery of Monte Cassino, near Cassino, Principality of Benevento Medieval medical scholar. He was the first to translate Arabic medical works into Latin. His 37 translated books included The Total Art , a short version of The Royal Book by the 10th-century Persian physician 'Alī ibn al-'Abbās, introducing Islam's extensive knowledge of Greek medicine to the West. His translations of Hippocrates and Galen first gave the West a view of Greek medicine as a whole.