Act I, Signature V - (1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chronological Particular Timeline of Near East and Europe History

Introduction This compilation was begun merely to be a synthesized, occasional source for other writings, primarily for familiarization with European world development. Gradually, however, it was forced to come to grips with the elephantine amount of historical detail in certain classical sources. Recording the numbers of reported war deaths in previous history (many thousands, here and there!) initially was done with little contemplation but eventually, with the near‐exponential number of Humankind battles (not just major ones; inter‐tribal, dynastic, and inter‐regional), mind was caused to pause and ask itself, “Why?” Awed by the numbers killed in battles over recorded time, one falls subject to believing the very occupation in war was a naturally occurring ancient inclination, no longer possessed by ‘enlightened’ Humankind. In our synthesized histories, however, details are confined to generals, geography, battle strategies and formations, victories and defeats, with precious little revealed of the highly complicated and combined subjective forces that generate and fuel war. Two territories of human existence are involved: material and psychological. Material includes land, resources, and freedom to maintain a life to which one feels entitled. It fuels war by emotions arising from either deprivation or conditioned expectations. Psychological embraces Egalitarian and Egoistical arenas. Egalitarian is fueled by emotions arising from either a need to improve conditions or defend what it has. To that category also belongs the individual for whom revenge becomes an end in itself. Egoistical is fueled by emotions arising from material possessiveness and self‐aggrandizations. To that category also belongs the individual for whom worldly power is an end in itself. -

University of Lo Ndo N Soas the Umayyad Caliphate 65-86

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SOAS THE UMAYYAD CALIPHATE 65-86/684-705 (A POLITICAL STUDY) by f Abd Al-Ameer 1 Abd Dixon Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philoso] August 1969 ProQuest Number: 10731674 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731674 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2. ABSTRACT This thesis is a political study of the Umayyad Caliphate during the reign of f Abd a I -M a lik ibn Marwan, 6 5 -8 6 /6 8 4 -7 0 5 . The first chapter deals with the po litical, social and religious background of ‘ Abd al-M alik, and relates this to his later policy on becoming caliph. Chapter II is devoted to the ‘ Alid opposition of the period, i.e . the revolt of al-Mukhtar ibn Abi ‘ Ubaid al-Thaqafi, and its nature, causes and consequences. The ‘ Asabiyya(tribal feuds), a dominant phenomenon of the Umayyad period, is examined in the third chapter. An attempt is made to throw light on its causes, and on the policies adopted by ‘ Abd al-M alik to contain it. -

Proquest Dissertations

The history of the conquest of Egypt, being a partial translation of Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam's "Futuh Misr" and an analysis of this translation Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hilloowala, Yasmin, 1969- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:08:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282810 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectiotiing the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Jewish Pilgrims to Palestine

Palestine Exploration Quarterly ISSN: 0031-0328 (Print) 1743-1301 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ypeq20 Jewish Pilgrims to Palestine Marcus N. Adler To cite this article: Marcus N. Adler (1894) Jewish Pilgrims to Palestine, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 26:4, 288-300, DOI: 10.1179/peq.1894.26.4.288 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/peq.1894.26.4.288 Published online: 20 Nov 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 6 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ypeq20 Download by: [Universite Laval] Date: 06 May 2016, At: 16:50 288 JEvVISH PILGRIMS TO PALESTINE. JEWISH, PILGRIMS TO PALESTINE. By MARCUS N. ADLER, M.A. IN response to th~ desire expressed by the Committee. of the Palestine Exploration Fund, I have much pleasure in furnishing a short account of the works of the early Jewish travellers in the East, and I propose also to give extracts from some of their writings which have reference to Palestine. Even prior to the destruction of the Second Temple, Jews were settled in most of the known countries of antiquity, and kept up com- munication with the land of their fathers. Passages from the Talmud prove that the sage Rabbi Akiba, who led the insurrection of the Jews against Hadrian, had visited many countries, notably Italy, Gaul, .Africa, Asia Minor, Persia, and Arabia. The Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds, the Midrashim and other Jewish writings up to the ninth century, contain innumerable references to the geography of Palestine. -

Full Palestine Timeline

Ancient History 12500 - 9500 BCE Natufian Culture 8500 – 6000 BCE Jericho and Large Settlements 3000 – 1200 BCE The Bronze Age 2000 BCE The Story of Abraham 1208 BCE Merneptah Stele & Extra Biblical Records 1020 BCE The United Kingdom of Israel – Hebrew Bible 930 BCE A Split Region 925 BCE Pharaoh Shoshenq Invades Canaan 738 BCE Neo-Assyrian Empire & Invasion of Israel 626 – 539 BCE Neo-Babylonian Empire 550 – 330 BCE The Achaemenid Empire & Cyprus the Great 330 BCE Alexander the Great Conquers Persian Empire 312 – 63 BCE The Seleucid Empire 116 BCE The Seleucid Empire Civil War The Rise of Christianity 63 BCE The Roman Republic Conquers Judea 66 – 136 Jewish & Roman Wars Diaspora 132 Hadrian Joins Syria and Judea 270 – 273 The Palmyrene Empire 306 – 324 Roman Civil Wars & Emperor Constantine The Rise of Islam 570 Approx. Birth of Muhammad 614 Sasanian Empire Captures Palestine 628 The Byzantines Recapture Palestine 632 – 661 The Rashidun Caliphate 662 – 750 The Ummayad Caliphate 750 – 1258 The Abbasid Caliphate The Crusades 1095 – 1099 Pope Urban Calls for 1st Crusade 1187 Saladin’s Campaign The Rise of Islam (cont.) 1206 Genghis Khan Declared Ruler of Mongolia 1251 Mongke Khan Extends the Empire 1250 – 1517 The Mamluk Sultanate 1516 The Ottoman Empire Conquers Palestine 1834 The Peasant’s Revolt 1840 The Convention of London The Rise of Zionism 1860 The 1st Jewish Neighbourhood 1882 – 1903 Jewish Migration 1897 1st Zionist Congress 1915 Britain’s Promise of Independence 1917 The Balfour Declaration 1917 – 1918 Britain Secures Jerusalem -

6.5 X 11.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88911-7 - Ancient Empires: From Mesopotamia to the Rise of Islam Eric H. Cline and Mark W. Graham Index More information INDEX Abbas, 338 Akhenaten, 24, 28 Abbasids, 322, 339, 340 Akhetaten, 28 Abd al-Malik, 319, 333, 336 Akitu Festival, 87, 91 Abraham, 73 Akkad, 17, 92, 184 Abu Bakr, 329, 330 Akkadian, 37, 38, 88, 100 Abu Simbel, 25 Akkadian dynasty, 18 Achaean League, 153, 176, 204, 208 Aksumites. See Ethiopian Achilles, 144 Alalia, 180 Actium, 221 Alamanni, 241 Actium, Battle of, 225, 226, 228, 260 Alans, 317 Adad, 68 Alaric, 317 Adad-guppi, 88, 90 Alba, 185 Adad-nirari II, 38 Alcibiades, 139, 140 adani, 60 Aleppo, 23 Adini, 64 Aleria, 192 Adrianople, Battle of, 317 Alexander IV, 150, 152 Adriatic, 204 Alexander the Great, 128, 142–148, 157–168 Aegean, 11, 12, 23, 24, 26, 30, 34, 36, 104, 107, cult of, 156 108, 110, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 122, 128, an example for Islam, 300 135, 152, 155, 173, 178, 180 an example for Rome, 174–176, 209–210, 219, Aemilius Paullus, 207 295, 299–300, 324 Aeschylus, 127, 130, 131, 132, 133 legacy, 85, 150–151, 158, 204 Agamemnon, 132 Alexanders Isle, 276 Eumenides, the, 132 Alexandria, 151, 159, 160, 162, 168, 324, 330 Persians, The, 130 Alexandropolis, 159 Prometheus Bound, 132 Ali ibn Abi Talib, 332, 339 Seven against Thebes, 132 Al Mina, 112 Afghanistan, 93, 144, 159, 167, 294 Alps, 202 Africa, 24, 69, 150, 203, 328 Amarna Letters, 28, 29, 68 ager publicus, 214, 215 Amenhotep IV, 28 Agricola, 259 America, 196 Agrippa, Marcus, 225 amici, 194 Ahab, 39, 62, 63, 75 amicitia, 187 Ahijah, 74 Ammianus Marcellinus, 310 Ahl al-Kitab, 335 Ammonites, 64 Ahriman, 97 Amon, 24, 30, 68 Ahura-Mazda, 96, 97, 98, 99, 116, 124, 193, 295, Amon-Re, 24, 25, 68 308 Amorites, 18 Ai Khanoum, 159, 162 Amos, 76, 90 Aitolian League, 153, 205 Amun, 144 Aitolians, 153 Amurru, 35 357 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88911-7 - Ancient Empires: From Mesopotamia to the Rise of Islam Eric H. -

Women and Islamic Cultures: a Bibliography of Books and Articles in European Languages Since 1993

Women and Islamic Cultures: A Bibliography of Books and Articles in European Languages since 1993 General Editor Suad Joseph Compiled by: G. J. Rober C. H. Bleaney V. Shepherd Originally Published in EWIC Volume I: Methodologies, Paradigms and Sources 2003 BRILL AFGHANISTAN 453 Afghanistan Articles 22 ACHINGER, G. Formal and nonformal education of Books female Afghan refugees: experiences in the rural NWFP refugee camps. Pakistan Journal of Women's Studies. Alam-e-Niswan, 3 i (1996) pp.33-42. 1 ARMSTRONG, Sally. Veiled threat: the hidden power of the women of Afghanistan. Toronto & London: Penguin, 23 CENTLIVRES-DEMONT, M. Les femmes dans le conflit 2002. 221pp. afghan. SGMOIK/SSMOCI Bulletin, 2 (1996) pp.16-18. 2 BRODSKY, Anne E. With all our strength: the 24 COOKE, Miriam. Saving brown women. Signs, 28 i Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan. (2002) pp.468-470-. Also online at http:// London: Routledge, 2003. 320pp. www.journals.uchicago.edu [From section headed "Gender and September 11". US attitude to Afghan women.] 3 (BROWN, A.Widney, BOKHARI, Farhat & others) Humanity denied: systematic denial of women's rights in 25 CORNELL, Drucilla. For RAWA. Signs, 28 i (2002) Afghanistan. New York: Human Rights Watch, 2001 pp.433-435. Also online at http:// (Human Rights Watch, 13/5), 27pp. Also online at www.journals.uchicago.edu [Revolutionary Association www.hrw.org/reports/2001/afghan3 of the Women of Afghanistan. From section headed "Gender and September 11"] 4 DELLOYE, Isabelle. Femmes d'Afghanistan. Paris: Phébus, 2002. 186pp. 26 DUPREE, N. H. Afghan women under the Taliban. Fundamentalism reborn? Afghanistan and the Taliban. -

On the Roman Frontier1

Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Impact of Empire Roman Empire, c. 200 B.C.–A.D. 476 Edited by Olivier Hekster (Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Lukas de Blois Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt Elio Lo Cascio Michael Peachin John Rich Christian Witschel VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/imem Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes and Michael Peachin LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016036673 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1572-0500 isbn 978-90-04-32561-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-32675-0 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Syria: Land of History, Civilizations and War

OVERVIEW Syria: Land of history, civilizations and war Mazigh M1* Affiliation Abstract 1International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group, Ottawa, ON As the Syrians are welcomed into Canada, it is useful to learn about where they are coming from. Syria is an ancient land with a rich history and has always been home to diverse cultures, *Correspondence: national. ethnicities and religions. Palmyra was an ancient civilization that arose during the second [email protected] century. Syria became part of the land of Islam in AD 640 and was a cultural, religious and artistic center. During the Middle Ages, Syria came under the control of the Crusaders and was part of the Ottoman Empire from the early fifteen hundreds until the end of the nineteenth century. During World War I it came under French influence and was recognized as an independent nation after World War II. In 1963, Hafez al-Assad led a military coup and since then, Syria has been ruled under emergency law. After al-Assad died in 2000, his son Bashar al-Assad was elected President in an uncontested presidential campaign. Before the current conflict, Syria had a population of approximately 22 million people but now about half the population have been displaced internally and into neighbouring countries, including approximately four million refugees. It is estimated that 250,000 people have died during the Syrian conflict. Suggested citation: Mazigh M. Syria: Land of history, civilizations and war. Can Comm Dis Rep 2016;42-Suppl 2:S1-2. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v42is2a01 Introduction In terms of religion, approximately three quarters of the people are Muslims including both Sunnis, who constitute the Syria is an ancient land with a rich history that has always been largest religious group and Shiites such as Ismailis, Twelvers home to diverse cultures, ethnicities and religions. -

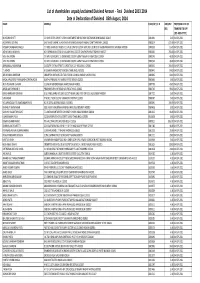

Final Dividend 2013-2014

List of shareholders unpaid/unclaimed Dividend Amount - Final Dividend 2013 -2014 Date of Declaration of Dividend : 05th August, 2014 NAME ADDRESS FOLIO/DP_CL ID AMOUNT PROPOSED DATE OF (RS) TRANSFER TO IEPF ( DD-MON-YYYY) MUKESH B BHATT C O SHRI DEVEN JOSHI 7 SURBHI APARTMENT NEHRU PARK VASTRAPUR AHMEDABAD 380015 0001091 8.0004-SEP-2021 AGGARWAL DEV RAJ SHIV SHAKTI SADAN 14 ASHOK VIHAR MAHESH NAGAR AMBALA CANTT HARYANA 134003 0000014 672.0004-SEP-2021 ROSHAN DADIBA ARSIWALLA C O MISS SHIRIN OF CHOKSI F 2 DALAL ESTATE F BLOCK GROUND FLOOR DR D BHADKAMKAR ROAD MUMBAI 400008 0000158 16.0004-SEP-2021 ACHAR MAYA MADHAV NO 9 BRINDAVAN 353 B 10 VALLABH BHAG ESTATE GHATKOPAR EAST BOMBAY 400077 0000030 256.0004-SEP-2021 YASH PAL ARORA C O MR K L MADAN C 19 DAYANAND COLONY LAJPAT NAGAR IV NEW DELHI 110024 0000343 48.8004-SEP-2021 YASH PAL ARORA C O MR K L MADAN C 19 DAYANAND COLONY LAJPAT NAGAR IV NEW DELHI 110024 0000344 48.8004-SEP-2021 ANNAMALAL RABINDRAN 24 SOUTH CHITRAI STREET C O POST BOX 127 MADURAI 1 625001 0000041 256.0004-SEP-2021 T J ASHOK M 51 ANNA NAGAR EAST MADRAS TAMIL NADU 600102 0000441 84.0004-SEP-2021 ARUN BABAN AMBEKAR CROMPTON GREAVES LTD TOOL ROOM A 3 MIDC AMBAD NASIK 422010 0000445 40.0004-SEP-2021 MAZHUVANCHERY PARAMBATH KORATHJACOB ILLATHU PARAMBU AYYAMPILLY PORT KERALA 682501 0005464 8.0004-SEP-2021 ALKA TUKARAM CHAVAN 51 5 NEW MUKUNDNAGAR AHMEDNAGAR 414001 0000709 40.0004-SEP-2021 ANGOLKAR SHRIKANT B PRABHU KRUPA M F ROAD NOUPADA THANE 400602 0000740 98.0004-SEP-2021 MIRZA NAWSHIR HOSHANG D 52 PANDURANG HOUSING SOCIETY -

Antarah (Antar) Ibn Shaddad - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Antarah (Antar) Ibn Shaddad - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 Antarah (Antar) Ibn Shaddad(525 - 615) 'Antarah Ibn Shaddad al-'Absi was a pre-Islamic Arabian hero and poet (525- 608) famous both for his poetry and his adventurous life. What many consider his best or chief poem is contained in the Mu'allaqat. The account of his life forms the basis of a long and extravagant romance. <b>Biography</b> Antarah was born in Najd (northern Saudi Arabia). He was the son of Shaddad, a well-respected member of the Arabian tribe of Banu Abs, his mother was named Zabibah, an Ethiopian woman, whom Shaddad had enslaved after a tribal war. The tribe neglected Antara at first, and he grew up in servitude. Although it was fairly obvious that Shaddad was his father. He was considered one of the "Arab crows" (Al-aghribah Al-'Arab) because of his jet black complexion. Antara gained attention and respect for himself by his remarkable personal qualities and courage in battle, excelling as an accomplished poet and a mighty warrior. He earned his freedom after one tribe invaded Banu Abs, so his father said to Him: "Antara fight with the warriors". Then he looked at his father in resentment and said: "The slave doesn't know how to invade or how to defend, but the slave is only good for milking goats and serving his masters". Then his father said: "Defend your tribe and you are free", then Antarah fought and expelled the invading tribes. -

Hobal, Allah Et Ses Filles

HOBAL, ALLAH ET SES FILLES Un petit dictionnaire des 360 dieux de la Jahiliyya Viens me conter fleurette ! me dit-elle. -Non, lui répondis-je ; ni Allah ni l'islam ne te le permettent. N'as-tu pas vu Muhammad et ses gens, lors de la conquête, le jour où les idoles étaient brisées ? On voyait alors resplendir la lumière d’Allah, alors que le polythéisme se couvrait de ténèbres. Radhid ibn Abdallah as Sulami. Autrefois, et durant des siècles, une quantité innombrable et prodigieuse de puissances divines a été vénérée en Arabie1, sans provoquer aucun trouble, sans générer aucune 1 in al Kalbi, Livre des Idoles 27b (ed. W. Atallah, Paris, 1966); R. Klinke-Rosenberger, Das Götzenbuch Kitab al-Aqnam of Ibn al-Kalbi, Leipzig, 1941; F. Stummer, "Bemerkungen zum Götzenbuch des Ibn al-Kalti," Zeitschrift der Deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft 98 1944; M. S. Marmadji, "Les dieux du paganisme arabe d'après Ibn al-Kalbi," RB 35 1926; H. S. Nyberg, “Bemerkungen Zum "Buch der Götzenbilder" von Ibn al-Kalbi”, in APARMA, Mel. Martin P. Nilsson, Lund, 1939; A. Jepsen, "Ibn al-Kalbis Buch der Götzenbilder. Aufbau und Bedeutung," Theo Litera-tur-Zeitung, 72, 1947 ; F. Zayadine, "The Pantheon of the Nabataean Inscriptions in Egypt and the Sinai", ARAM 2, 1990, Mitchell J. Dahood, “Ancient Semitic Deities in Syria and Palestine”, in Sabatino Moscati, ed., Le Antiche Divinità Semitiche, Roma, 1958; F. Zayadine, “Les dieux nabatéens” , Les Dossiers d'Archéologie 163/1991 ;J. F. Healey, The Religion Of Nabataeans: A Conspectus, Leiden 2001;Estelle Villeneuve, “Les grands dieux de la Syrie ancienne”, Les religions de la Syrie antique , Le Monde de la Bible , 149/2003 ; Maurice Sartre “Panthéons de la Syrie hellénistique”, Les religions de la Syrie 1 catastrophe, tant pour l’Arabie que pour les régions voisines et pour le reste de l'humanité.