University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RES 2014.08.12 Thiessen on Frevel and Nihan Purity and the Forming

Reviews of the Enoch Seminar 2014.08.12 Christian Frevel and Christophe Nihan, eds. Purity and the Forming of Religious Traditions in the Ancient Mediterranean World and Ancient Judaism . Dynamics in the History of Religion 3. Leiden: Brill, 2012. Pp. xv + 601. ISBN 9789004232105. Hardcover. €192.00/ $267.00. Matthew Thiessen Saint Louis University This edited volume is based upon a 2008-2009 workshop entitled “Purity in Processes of Social, Cultural and Religious Differentiation,” which took place at the University of Bochum, Germany. It consists of an introduction, eighteen essays surveying purity ideologies in numerous ancient Mediterranean cultures, and three indices. The introduction states the purpose of the editors: the book “aims at offering a comprehensive discussion of the development, transformation and mutual influence of concepts of purity in major ancient Mediterranean cultures and religions from a comparative perspective, with a specific focus on ancient Judaism” (2). The majority of the introduction examines ritual theory, especially the work of Mary Douglas and Catherine Bell. Its broader statements about purity and ritual are then put to the test in the individual essays. The introduction ends with a helpful bibliography focusing on ritual purity systems. The first nine essays focus on conceptions of purity/impurity in non-Jewish cultures and contexts. Michaël Guichard and Lionel Marti survey the concept of purity in ancient Mesopotamia, a difficult task in light of both the wealth of material and the absence of a more systematic account of impurity such as can be found in the book of Leviticus. Their essay discusses evidence from two periods: Sumerian literature dating to 2150-1600 BCE and Neo- Assyrian literature dating to the 9th-6th centuries BCE . -

The Contemporary Renaissance of Enoch Studies, and the Enoch Seminar

INTRODUCTION: THE CONTEMPORARY RENAISSANCE OF ENOCH STUDIES, AND THE ENOCH SEMINAR In the winter 2000, a group of specialists in Enoch literature began cor- responding via e-mail and decided to meet the following year in Flor- ence, Italy (many of them for the very rst time, face to face) not to present papers but to discuss in a seminar format the results of their research. George Nickelsburg had just completed the manuscript of the rst volume of his monumental commentary on 1 Enoch (1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch, Chapters 1–36; 81–108, Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2001). Several other specialists, in the United States, Europe, and Israel, were studying the same material as evidence for a distinct stream of apocalyptic thought in Second Temple Juda- ism. Working autonomously these scholars had opened new, convergent paths in the understanding of the Enoch literature. The time was ripe for them to share their experiences. It took the technological innovation of the electronic mail, however, to make it possible for them to com- municate and organize a meeting in just a few months. By the summer 2000, the Enoch Seminar was of\cially born. The Experience of the First Enoch Seminars The rst meeting of the Enoch Seminar was held in Sesto Fiorentino, Florence, Italy (19–23 June 2001) at the Villa Corsi-Salviati, home of the University of Michigan in Italy, and focused on “The Origins of Enochic Judaism”. The meeting promoted the “rediscovery” of Enochic Judaism and the study of ancient Enoch literature as evidence for an ancient movement of dissent within Second Temple Judaism. -

RES 2015.12.15 Bertalotto on the Institution of the Hasmonean High

Reviews of the Enoch Seminar 2015.12.15 Vasile Babota, The Institution of the Hasmonean High Priesthood . Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism 165. Leiden: Brill, 2014. ISBN: 978900425177. € 123 / $ 171. Hardback. Pierpaolo Bertalotto Bari, Italy The aim of this book is to define more adequately the Hasmonean high priesthood as an institution in comparison with the biblical / Jewish tradition on the one hand and the Hellenistic / Seleucid world on the other. Were the Hasmonean high priests more like preexilic kings, like priests from the Oniad or Zadokite families, or like Hellenistic king-priests? This is the question that continually surfaces throughout the entire book. The study contains an introduction, ten chapters, final conclusions, a full bibliography, an index of ancient people, and an index of ancient sources. The introduction offers a brief presentation of the scholarly work on high priestly office which focuses on the relationship among the Hasmonean high priesthood, the Jewish tradition, and the Hellenistic world. Babota then begins his analysis by describing the sources for his study. He considers 1 Maccabees a unitary pro-Hasmonean work written at the time of John Hyrcanus I, probably soon before his death, whose aim is to strengthen his position as high priest in the line of Simon. This strong political agenda must be taken into account when using this literary work as a historical source: its reliability must be assessed, as the author consistently does, on a case by case basis. Concerning 2 Maccabees, Babota especially emphasizes its pro-Judas stance. It is therefore less favorable towards Jonathan and Simon than 1 Maccabees and to some extent critical of the establishment of the Hasmonean high priesthood. -

A HARMONY of JUDEO-CHRISTIAN ESCHATOLOGY and MESSIANIC PROPHECY James W

African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research ISSN: 2689-5129 Volume 4, Issue 3, 2021 (pp. 65-80) www.abjournals.org A HARMONY OF JUDEO-CHRISTIAN ESCHATOLOGY AND MESSIANIC PROPHECY James W. Ellis Cite this article: ABSTRACT: This essay presents a selective overview of the James W. Ellis (2021), A main themes of Judeo-Christian eschatological prophecy. Harmony of Judeo-Christian Particular attention is paid to the significance of successive Eschatology and Messianic biblical covenants, prophecies of the “day of the Lord,” Prophecy. African Journal of Social Sciences and differences between personal and collective resurrection, and Humanities Research 4(3), 65- expectations of the Messianic era. Although the prophets of the 80. DOI: 10.52589/AJSSHR- Hebrew Bible and Christian New Testament lived and wrote in 6SLAJJHX. diverse historical and social contexts, their foresights were remarkably consistent and collectively offered a coherent picture Manuscript History of the earth’s last days, the culmination of human history, and the Received: 24 May 2021 prospects of the afterlife. This coherence reflects the interrelated Accepted: 22 June 2021 character of Judaic and Christian theology and the unity of the Judeo-Christian faith. Published: 30 June 2021 KEYWORDS: Eschatology, Judeo-Christian, Messiah, Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Prophecy. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits anyone to share, use, reproduce and redistribute in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. 65 Article DOI: 10.52589/AJSSHR-6SLAJJHX DOI URL: https://doi.org/10.52589/AJSSHR-6SLAJJHX African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research ISSN: 2689-5129 Volume 4, Issue 3, 2021 (pp. -

Reviews of the Enoch Seminar 2018.11.10 Edmon L. Gallagher And

Reviews of the Enoch Seminar 2018.11.10 Edmon L. Gallagher and John D. Meade. The Biblical Canon Lists from Early Christianity: Texts and Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. £35/€40. ISBN 9780198792499. Pp. 359. Hardcover. Juan Carlos Ossandón Pontificia Università della Santa Croce Italy Edmon L. Gallagher (Associate Professor of Christian Scripture, Heritage Christian University in Florence, Alabama) is well known in academic circles for a monograph and several articles on the history of the canon. In the case of John D. Meade (Associate Professor of Old Testament, Phoenix Seminary in Phoenix, Arizona), this is his first publication in the field of biblical canon studies. His dissertation on the hexaplaric fragments of Job 22–42 is forthcoming with Peeters. In the introduction (xii–xxii), the authors state that their aim is to present “the evidence of the early Christian canon lists in an accessible form for the benefit of students and scholars” (xii), where “early” refers to the first four centuries of our era. They intend to gather all these lists, to introduce them, to present them both in their original language and in English translation—often taking it from elsewhere, sometimes offering their own—and to provide scholarly literature for further discussion (see pp. xviii–xx). As they explain on p. xix, their book contains three lists that do not correspond to the initial promise: one from the fifth century, the list of Pope Innocent (231–235), and two non-Christian lists, that of Flavius Josephus in Against Apion and that of the Babylonian Talmud. The work is structured in six chapters. -

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death Remi Jedwab and Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama⇤ April 16, 2018 Abstract We study the Black Death pogroms to shed light on the factors determining when a minority group will face persecution. In theory, negative shocks increase the likelihood that minorities are persecuted. But, as shocks become more severe, the persecution probability decreases if there are economic complementarities between majority and minority groups. The effects of shocks on persecutions are thus ambiguous. We compile city-level data on Black Death mortality and Jewish persecutions. At an aggregate level, scapegoating increases the probability of a persecution. However, cities which experienced higher plague mortality rates were less likely to persecute. Furthermore, for a given mortality shock, persecutions were less likely in cities where Jews played an important economic role and more likely in cities where people were more inclined to believe conspiracy theories that blamed the Jews for the plague. Our results have contemporary relevance given interest in the impact of economic, environmental and epidemiological shocks on conflict. JEL Codes: D74; J15; D84; N33; N43; O1; R1 Keywords: Economics of Mass Killings; Inter-Group Conflict; Minorities; Persecutions; Scapegoating; Biases; Conspiracy Theories; Complementarities; Pandemics; Cities ⇤Corresponding author: Remi Jedwab: Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, George Washington University, [email protected]. Mark Koyama: Associate -

Download File

THE BOOK OF JUBILEES AMONG THE APOCALYPSES VOLUME II A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Todd Russell Hanneken James C. VanderKam, Director Graduate Program in Theology Notre Dame, Indiana June 2008 CONTENTS Volume II Chapter 5: The Spatial Axis.............................................................................................261 5.1. Angels and demons............................................................................................264 5.1.1. Before the flood: the origin of evil..........................................................265 5.1.1.1. The Enochic apocalypses ..............................................................265 5.1.1.2. The Danielic apocalypses..............................................................268 5.1.1.3. Jubilees..........................................................................................269 5.1.2. After the flood: the persistence of demons..............................................272 5.1.2.1. The early apocalypses ...................................................................273 5.1.2.2. Jubilees..........................................................................................274 5.1.3. Angelic mediation ...................................................................................277 5.1.3.1. Evidence outside the apocalypses .................................................277 5.1.3.2. The early apocalypses ...................................................................281 -

Early Jewish Writings

EARLY JEWISH WRITINGS Press SBL T HE BIBLE AND WOMEN A n Encyclopaedia of Exegesis and Cultural History Edited by Christiana de Groot, Irmtraud Fischer, Mercedes Navarro Puerto, and Adriana Valerio Volume 3.1: Early Jewish Writings Press SBL EARLY JEWISH WRITINGS Edited by Eileen Schuller and Marie-Theres Wacker Press SBL Atlanta Copyright © 2017 by SBL Press A ll rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office,S BL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schuller, Eileen M., 1946- editor. | Wacker, Marie-Theres, editor. Title: Early Jewish writings / edited by Eileen Schuller and Marie-Theres Wacker. Description: Atlanta : SBL Press, [2017] | Series: The Bible and women Number 3.1 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers:L CCN 2017019564 (print) | LCCN 2017020850 (ebook) | ISBN 9780884142324 (ebook) | ISBN 9781628371833 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780884142331 (hardcover : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Bible. Old Testament—Feminist criticism. | Women in the Bible. | Women in rabbinical literature. Classification: LCC BS521.4 (ebook) | LCC BS521.4 .E27 2017 (print) | DDC 296.1082— dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019564 Press Printed on acid-free paper. -

On Saints, Sinners, and Sex in the Apocalypse of Saint John and the Sefer Zerubbabel

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Theology & Religious Studies College of Arts and Sciences 12-30-2016 On Saints, Sinners, and Sex in the Apocalypse of Saint John and the Sefer Zerubbabel Natalie Latteri Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/thrs Part of the Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Social History Commons Apocalypse of St. John and the Sefer Zerubbabel On Saints, Sinners, and Sex in the Apocalypse of St. John and the Sefer Zerubbabel Natalie E. Latteri, University of New Mexico, NM, USA Abstract The Apocalypse of St. John and the Sefer Zerubbabel [a.k.a Apocalypse of Zerubbabel] are among the most popular apocalypses of the Common Era. While the Johannine Apocalypse was written by a first-century Jewish-Christian author and would later be refracted through a decidedly Christian lens, and the Sefer Zerubbabel was probably composed by a seventh-century Jewish author for a predominantly Jewish audience, the two share much in the way of plot, narrative motifs, and archetypal characters. An examination of these commonalities and, in particular, how they intersect with gender and sexuality, suggests that these texts also may have functioned similarly as a call to reform within the generations that originally received them and, perhaps, among later medieval generations in which the texts remained important. The Apocalypse of St. John and the Sefer Zerubbabel, or Book of Zerubbabel, are among the most popular apocalypses of the Common Era.1 While the Johannine Apocalypse was written by a first-century Jewish-Christian author and would later be refracted through a decidedly Christian lens, and the Sefer Zerubbabel was probably composed by a seventh-century Jewish author for a predominantly Jewish audience, the two share much in the way of plot, narrative motifs, and archetypal characters. -

Abbreviations and Bibliography

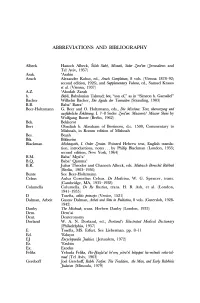

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Torah and Western Thought: Jewish and Western Texts in Conversation

Torah and Western Thought: Jewish and Western Texts in Conversation DECEMBER 2020 Winston Spencer Maccabee BY RABBI DR. MEIR Y. SOLOVEICHIK This article originally appeared in the February 2018 issue of Commentary Magazine. In 1969, Winston Churchill’s biographer Martin was speaking on a celebratory day in the Christian Gilbert interviewed Edward Lewis Spears, a longtime calendar, Churchill then concluded with an apparent friend of Gilbert’s subject. “Even Winston had a fault,” scriptural citation—a rare rhetorical choice for him— Spears reflected to Gilbert. “He was too fond of Jews.” If, as inspiration to his country at the most perilous moment as one British wag put it, an anti-Semite is one who hates in its history. the Jews more than is strictly necessary, Churchill was believed to admire the Jews more than elite British Today is Trinity Sunday. Centuries ago words society deemed strictly necessary. With attention now were written to be a call and a spur to the being paid to Churchill’s legacy as portrayed in the film faithful servants of Truth and Justice: “Arm Darkest Hour, I thought it worth exploring the little- yourselves, and be ye men of valour, and be in known role that Churchill’s fondness for the Jewish readiness for the conflict; for it is better for us to people played at a critical period in the history of Western perish in battle than to look upon the outrage of civilization. our nation and our altar. As the Will of God is in Heaven, even so let it be.” The film highlights three addresses delivered by Churchill upon becoming prime minister in the spring of 1940, with Thus ended Churchill’s first radio address as prime the Nazis bestriding most of Europe. -

Reasonable Man’

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2019 The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ Johnny Sakr The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Law Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Sakr, J. (2019). The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ (Master of Philosophy (School of Law)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/215 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Conjecture from the Universality of Objectivity in Jurisprudential Thought: The Universal Presence of a ‘Reasonable Man’ By Johnny Michael Sakr Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy University of Notre Dame Australia School of Law February 2019 SYNOPSIS This thesis proposes that all legal systems use objective standards as an integral part of their conceptual foundation. To demonstrate this point, this thesis will show that Jewish law, ancient Athenian law, Roman law and canon law use an objective standard like English common law’s ‘reasonable person’ to judge human behaviour.