Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100-1800⇤

Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100-1800⇤ § Robert Warren Anderson† Noel D. Johnson‡ Mark Koyama University of Michigan, Dearborn George Mason University George Mason University This Version: 30 December, 2013 Abstract What factors caused the persecution of minorities in medieval and early modern Europe? We build amodelthatpredictsthatminoritycommunitiesweremorelikelytobeexpropriatedinthewake of negative income shocks. Using panel data consisting of 1,366 city-level persecutions of Jews from 936 European cities between 1100 and 1800, we test whether persecutions were more likely in colder growing seasons. A one standard deviation decrease in average growing season temperature increased the probability of a persecution between one-half and one percentage points (relative to a baseline probability of two percent). This effect was strongest in regions with poor soil quality or located within weak states. We argue that long-run decline in violence against Jews between 1500 and 1800 is partly attributable to increases in fiscal and legal capacity across many European states. Key words: Political Economy; State Capacity; Expulsions; Jewish History; Climate JEL classification: N33; N43; Z12; J15; N53 ⇤We are grateful to Megan Teague and Michael Szpindor Watson for research assistance. We benefited from comments from Ran Abramitzky, Daron Acemoglu, Dean Phillip Bell, Pete Boettke, Tyler Cowen, Carmel Chiswick, Melissa Dell, Dan Bogart, Markus Eberhart, James Fenske, Joe Ferrie, Raphäel Franck, Avner Greif, Philip Hoffman, Larry Iannaccone, Remi Jedwab, Garett Jones, James Kai-sing Kung, Pete Leeson, Yannay Spitzer, Stelios Michalopoulos, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Naomi Lamoreaux, Jason Long, David Mitch, Joel Mokyr, Johanna Mollerstrom, Robin Mundill, Steven Nafziger, Jared Rubin, Gail Triner, John Wallis, Eugene White, Larry White, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. -

Olena Semenyaka, the “First Lady” of Ukrainian Nationalism

Olena Semenyaka, The “First Lady” of Ukrainian Nationalism Adrien Nonjon Illiberalism Studies Program Working Papers, September 2020 For years, Ukrainian nationalist movements such as Svoboda or Pravyi Sektor were promoting an introverted, state-centered nationalism inherited from the early 1930s’ Ukrainian Nationalist Organization (Orhanizatsiia Ukrayins'kykh Natsionalistiv) and largely dominated by Western Ukrainian and Galician nationalist worldviews. The EuroMaidan revolution, Crimea’s annexation by Russia, and the war in Donbas changed the paradigm of Ukrainian nationalism, giving birth to the Azov movement. The Azov National Corps (Natsional’nyj korpus), led by Andriy Biletsky, was created on October 16, 2014, on the basis of the Azov regiment, now integrated into the Ukrainian National Guard. The Azov National Corps is now a nationalist party claiming around 10,000 members and deployed in Ukrainian society through various initiatives, such as patriotic training camps for children (Azovets) and militia groups (Natsional’ny druzhiny). Azov can be described as a neo- nationalism, in tune with current European far-right transformations: it refuses to be locked into old- fashioned myths obsessed with a colonial relationship to Russia, and it sees itself as outward-looking in that its intellectual framework goes beyond Ukraine’s territory, deliberately engaging pan- European strategies. Olena Semenyaka (b. 1987) is the female figurehead of the Azov movement: she has been the international secretary of the National Corps since 2018 (and de facto leader since the party’s very foundation in 2016) while leading the publishing house and metapolitical club Plomin (Flame). Gaining in visibility as the Azov regiment transformed into a multifaceted movement, Semenyaka has become a major nationalist theorist in Ukraine. -

University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich

Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. Winterthurerstr. 190 CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007 Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. THE BOOK OF JUBILEES: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY FROM THE FIRST GERMAN TRANSLATION OF 1850 TO THE ENOCH SEMINAR OF 2007 ISAAC W. OLIVER , University of Michigan VERONIKA BACHMANN , University of Zurich The following annotated bibliography provides summaries of the most influential scholarly works dedicated to the Book of Jubilees written between 1850 and 2006. * The year 1850 opens the period of modern research on Jubilees thanks to Dillmann’s translation of the Ethiopic text of Jubilees into German; the Enoch Seminar of 2007 represents the largest gathering of international scholars on the document in modern times. -

Brief History of German Anti-Semitism

Chapter 1 Writings on the Wall Chapter 1 A Concise History of German Anti-Semitism In 1942, in a suburb of Berlin known as Wannsee, Reinhard Heydrich (head of the infamous Nazi secret police, the Gestapo) finalized the Nazi commitment to the extermination of the Jews within the Third Reich’s sphere of influence (Gilbert 281). According to some historians, these announcements made at Wannsee were the culmination of step-by-step decisions that had brought about what Adolf Hitler meant when, in 1920, he announced the Nazi party’s position that “None but members of the Nation may be citizens of the State. None but those of German blood, whatever their creed, may be members of the Nation. No Jew, therefore, may be a member of the Nation” (qtd. in Gilbert 23). Both ancient and contemporary European and German anti-Semitic forces were about to collide in Wannsee. That collision tragically ignited one of history’s most devastating and most documented genocidal conflagrations—what today is commonly called the “Holocaust.” Some historians suggest the Holocaust was the result of the Nazi targeting of Jews as scapegoats by suggesting that world-Jewry collectively had had something to do with the “stab in the back” that brought the World War I German war effort and World War I itself to a turbulent end. Some researchers suggest European Jewry was singled out for “special treatment” because they, the Jews, were somehow responsible for the unexpectedly final battlefield- failures, the consequent enormous war reparation payments, the collapsing stock markets and the subsequent spiraling inflation that financially crippled the German nation. -

Download Date 04/10/2021 06:40:30

Mamluk cavalry practices: Evolution and influence Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nettles, Isolde Betty Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:40:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289748 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this roproduction is dependent upon the quaiity of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that tfie author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.. maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal secttons with small overlaps. Photograpiis included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrattons appearing in this copy for an additk)nal charge. -

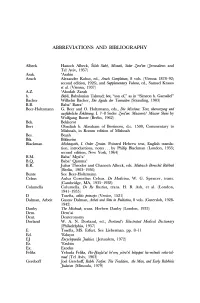

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

^Irticfe Es Jews in the World

^Irticfe es Jews in the World War A BRIEF HISTORICAL SKETCH By ABRAHAM G. DUKER HE outbreak of war in Europe adds a host of new problems to those left Tunsolved by the last World War. In many respects it was the failure to solve these problems which brought about the present conflict. The heavy toll of modern warfare, the vast sacrifices demanded of all people, the disasters from which society suffers are so great that only events of first magnitude make a lasting impression on the mind of the public. The smaller tragedies, however poignant, are noticed by only a few, and are soon forgotten. The effects of the World War on the Jews suffered this fate of obscurity. Yet, what happened to the Jews in that struggle has the markings of profound tragedy. Fighting in all the armies for their native lands, Jews, in many cases, were simultaneously forced to defend themselves against the hostility of the governments for which they fought. Victimized by many—but also befriended by many—the Jews bore a terribly disproportionate share of the sufferings imposed on humanity by the War. Today the theatre of conflict is once more in regions thickly populated by Jews; the destructiveness of war has reached unprecedented heights; and in some countries Jew-hatred has been elevated to the status of a national policy. The fate of the Jews in the last war is, therefore, a subject of timely importance. I NUMBER AND DISTRIBUTION OF JEWS IN 1914 Jews in the world today number more than sixteen million. -

Reasonable Man’

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2019 The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ Johnny Sakr The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Law Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Sakr, J. (2019). The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ (Master of Philosophy (School of Law)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/215 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Conjecture from the Universality of Objectivity in Jurisprudential Thought: The Universal Presence of a ‘Reasonable Man’ By Johnny Michael Sakr Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy University of Notre Dame Australia School of Law February 2019 SYNOPSIS This thesis proposes that all legal systems use objective standards as an integral part of their conceptual foundation. To demonstrate this point, this thesis will show that Jewish law, ancient Athenian law, Roman law and canon law use an objective standard like English common law’s ‘reasonable person’ to judge human behaviour. -

A Chronology of the Black Death (1347–1363)

A Chronology of the Black Death (1347–1363) 1347 Plague comes to the Black Sea region, Constantinople, Asia Minor, Sicily, Marseille on the southeastern coast of France, and perhaps the Greek archipelago and Egypt. 1348 Plague comes to all of Italy, most of France, the eastern half of Spain, southern England, Switzerland, Austria, the Balkans and Greece, Egypt and North Africa, Palestine and Syria, and perhaps Denmark. The flagellant movement begins in Austria or Hungary. Jewish pogroms occur in Languedoc and Catalonia, and the first trials of Jews accused of well poisoning take place in Savoy. 1349 Plague comes to western Spain and Portugal, central and north- ern England, Wales, Ireland, southern Scotland, the Low Coun- tries (Belgium and Holland), western and southern Germany, Hungary, Denmark, and Norway. The flagellants progress through Germany and Flanders before they are suppressed by order of Pope Clement VI. Burning of Jews on charges of well poisoning occurs in many German-speaking towns, including Strasbourg, Stuttgart, Con- stance, Basel, Zurich, Cologne, Mainz, and Speyer; in response, Pope Clement issues a bull to protect Jews. Some city-states in Italy and the king’s council in England pass labor legislation to control wages and ensure a supply of agricul- tural workers in the wake of plague mortality. 1350 Plague comes to eastern Germany and Prussia, northern Scot- land, and all of Scandinavia (Denmark, Norway, Sweden). King Philip VI of France orders the suppression of the flagellants in Flanders. The córtes, or representative assembly, of Aragon passes labor legislation. 179 180 CHRONOLOGY 1351– 1352 Plague comes to Russia, Lithuania, and perhaps Poland. -

Jewish and Christian Perspectives on ??????? in Genesis 20:13 in the Ancient, Mediaeval and Reformed Exegesis

MAJT 28 (2017): 135-147 IN הִתְעּו JEWISH AND CHRISTIAN PERSPECTIVES ON GENESIS 20:13 IN THE ANCIENT, MEDIAEVAL AND REFORMATION EXEGESIS by Matthew Oseka Introduction acted as the subject in Genesis אלהים for which ,(הִתְעּו) THE PLURAL FORM of the verb 20:13, was often brought up for discussion in the history of biblical exegesis. Modern commentaries1 tend to explain this intriguing form as Abraham’s accommodation to Abimelech’s polytheistic background, namely, as a rhetorical concession made by Abraham to Abimelech. Indeed, it is arguable that within the parameters of the narrative Abraham tried to appease Abimelech and therefore adopted the phrasing which was common and absolutely inconspicuous. From a historical perspective, the plural forms concerning the Divine (e.g. Gen. 1:26; 11:7; 20:13) acted as focal points for exegetical and theological discussions in Jewish and Christian traditions. Granted that the literature on the origin of the Jewish2 1. As typified by: August Dillmann, Genesis Critically and Exegetically Expounded, vol. 2, trans. William Black Stevenson (Edinburgh: Clark, 1897), 122 [Genesis 20:13]; Samuel Rolles Driver, The Book of Genesis with Introduction and Notes (London: Methuen, 1904), 208 [Genesis 20:13]; Carl Friedrich Keil, Biblischer Kommentar über die Bücher Mose’s, vol. 1 (Leipzig: Dörffling and Franke, 1878), 204 [Genesis 20:13]; Andrew J. Schmutzer, “Did the ”,in Genesis 20:13 התעו אתי אלהים Gods Cause Abraham’s Wandering? An Examination of Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 35/2 (2010); Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis: 16-50, WBC (Dallas: Word, 1998), 73 [Genesis 20:13]. -

Manasseh in Scripture and Tradition: an Analysis of Ancient Sources and the Development of the Manasseh Tradition Steven A

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Seminary Masters Theses Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2002 Manasseh in Scripture and Tradition: An Analysis of Ancient Sources and the Development of the Manasseh Tradition Steven A. Graham This research is a product of the Master of Arts in Theological Studies (MATS) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Graham, Steven A., "Manasseh in Scripture and Tradition: An Analysis of Ancient Sources and the Development of the Manasseh Tradition" (2002). Seminary Masters Theses. 38. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/seminary_masters/38 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seminary Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY MANASSEH IN SCRIPTURE AND TRADITION: AN ANALYSIS OF ANCIENT SOURCES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MANASSEH TRADITION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE DEPARTMENT OF MINISTRY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEOLOGICAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY BY STEVEN A. GRAHAM PORTLAND, OREGON MAY2002 PORTLAND CENTER LIBRARY GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY PORTLAND, OR. 97223 o,~w;, nnn i1ttll1J 1ww',;:, ',.!1 ;,~;:,n:::1 1m',, w,,,', ,:::1',-n~ ,nm1 1:::1 n1Jl1', 01~i1 ,J:::l', o,;,',~ 1m .!11 rJlJ ~1i1 I have given my heart to search and to seek by wisdom concerning all that has been done under heaven. It is a task of distress that God has given to the children of men to be afflicted with. -

The Medieval Origins of Anti-Semitic Violence in Nazi Germany

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES PERSECUTION PERPETUATED: THE MEDIEVAL ORIGINS OF ANTI-SEMITIC VIOLENCE IN NAZI GERMANY Nico Voigtlaender Hans-Joachim Voth Working Paper 17113 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17113 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2011 We thank Sascha Becker, Efraim Benmelech, Davide Cantoni, Dora Costa, Raquel Fernandez, Jordi Galí, Claudia Goldin, Avner Greif, Elhanan Helpman, Rick Hornbeck, Saumitra Jha, Matthew Kahn, Lawrence Katz, Deirdre McCloskey, Joel Mokyr, Petra Moser, Nathan Nunn, Steve Pischke, Leah Platt Boustan, Shanker Satyanath, Kurt Schmidheiny, Andrei Shleifer, Yannay Spitzer, Peter Temin, Matthias Thoenig, and Jaume Ventura for helpful comments. Seminar audiences at CREI, Harvard, NYU, Northwestern, Stanford, UCLA, UPF, Warwick, and at the 2011 Royal Economic Society Conference offered useful criticisms. We are grateful to Hans-Christian Boy for outstanding research assistance, and Jonathan Hersh, Maximilian von Laer, and Diego Puga for help with the geographic data. Davide Cantoni and Noam Yuchtman kindly shared their data on year of incorporation and first market for German cities. Voigtländer acknowledges financial support from the UCLA Center for International Business Education and Research (CIBER). Voth thanks the European Research Council for generous funding. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2011 by Nico Voigtlaender and Hans-Joachim Voth. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Persecution Perpetuated: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Semitic Violence in Nazi Germany Nico Voigtlaender and Hans-Joachim Voth NBER Working Paper No.