The Mechanics of Providence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Hebrew Letters in Making the Divine Visible

"VTSFDIUMJDIFO (SàOEFOTUFIU EJFTF"CCJMEVOH OJDIUJN0QFO "DDFTT[VS 7FSGàHVOH The Role of Hebrew Letters in Making the Divine Visible KATRIN KOGMAN-APPEL hen Jewish figural book art began to develop in central WEurope around the middle of the thirteenth century, the patrons and artists of Hebrew liturgical books easily opened up to the tastes, fashions, and conventions of Latin illu- minated manuscripts and other forms of Christian art. Jewish book designers dealt with the visual culture they encountered in the environment in which they lived with a complex process of transmis- sion, adaptation, and translation. Among the wealth of Christian visual themes, however, there was one that the Jews could not integrate into their religious culture: they were not prepared to create anthropomorphic representations of God. This stand does not imply that Jewish imagery never met the challenge involved in representing the Divine. Among the most lavish medieval Hebrew manu- scripts is a group of prayer books that contain the liturgical hymns that were commonly part of central European prayer rites. Many of these hymns address God by means of lavish golden initial words that refer to the Divine. These initials were integrated into the overall imagery of decorated initial panels, their frames, and entire page layouts in manifold ways to be analyzed in what follows. Jewish artists and patrons developed interesting strategies to cope with the need to avoid anthropomorphism and still to give way to visually powerful manifestations of the divine presence. Among the standard themes in medieval Ashkenazi illuminated Hebrew prayer books (mahzorim)1 we find images of Moses receiving the tablets of the Law on Mount Sinai (Exodus 31:18, 34), commemorated during the holiday of Shavuot, the Feast of Weeks (fig. -

Yom Kippur Additional Service

v¨J¨s£j jUr© rIz§j©n MACHZOR RUACH CHADASHAH Services for the Days of Awe ohrUP¦ ¦ F©v oIh§k ;¨xUn YOM KIPPUR ADDITIONAL SERVICE London 2003 - 5763 /o¤f§C§r¦e§C i¥T¤t v¨J¨s£j jU© r§ «u Js¨ ¨j c¥k o¤f¨k h¦T©,¨b§u ‘I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you.’ (Ezekiel 36:26) This large print publication is extracted from Machzor Ruach Chadashah EDITORS Rabbi Dr Andrew Goldstein Rabbi Dr Charles H Middleburgh Editorial Consultants Professor Eric L Friedland Rabbi John Rayner Technical Editor Ann Kirk Origination Student Rabbi Paul Freedman assisted by Louise Freedman ©Union of Liberal & Progressive Synagogues, 2003 The Montagu Centre, 21 Maple Street, London W1T 4BE Printed by JJ Copyprint, London Yom Kippur Additional Service A REFLECTION BEFORE THE ADDITIONAL SERVICE Our ancestors acclaimed the God Whose handiwork they read In the mysterious heavens above, And in the varied scene of earth below, In the orderly march of days and nights, Of seasons and years, And in the chequered fate of humankind. Night reveals the limitless caverns of space, Hidden by the light of day, And unfolds horizonless vistas Far beyond imagination's ken. The mind is staggered, Yet soon regains its poise, And peering through the boundless dark, Orients itself anew by the light of distant suns Shrunk to glittering sparks. The soul is faint, yet soon revives, And learns to spell once more the name of God Across the newly-visioned firmament. Lift your eyes, look up; who made these stars? God is the oneness That spans the fathomless deeps of space And the measureless eons of time, Binding them together in deed, as we do in thought. -

Jewish Prayer: New Perspectives

14:30-16:00 Ninth Session International Conference Prayer in Kabbalah and Hassidism Chair: Boaz Huss, Ben-Gurion University Moshe Ha llamish, Bar-Ilan University The Kabbalistic Contribution to the Benedictions of Jewish Prayer: Identity Bracha Sack, Ben-Gurion University New Perspectives Prayer as Shi'ur Qomah Jonatan Meir, Ben-Gurion University The History of Sefer Likutei Tefilot 11-13 Sivan 5773 16:15-17:45 Tenth Session 20.5.2013 - 22.5.2013 Prayer in the Modern Period Barkan Conference Room Chair: Yael Lin, Ben-Gurion University Zlotowski Student Administration Building George Y. Kohler, Bar-Ilan University The Refusal of the Early Reform Rabbis to Abandon The Marcus Family Campus Beer-Sheva Messianic Prayer Texts Zvi Mark, Bar-Ilan University Prayer and Mysticism in the Poetry of Zelda, Yona Wallach and Sivan Har-Shefi Dalia Marx, Hebrew Union College (Jerusalem) From the Rhine Valley to Jezreel Valley: New Formulations of the Kaddish Ben-Gurion University of theNegev 18:00-19:00 Concluding Session Chair: Haim Kreisel, Ben-Gurion University Moshe Idel, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem For information: [email protected] The Liturgical Turn from the Kabbalah of Safed to 972-8-6472532 Hasidism Visit the conference website All the lectures in Hebrew unless noted otherwise http://hsf.bgu.ac.il/cjt/prayer The Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought Monday May 20, 2013 Wednesday May 22, 2013 18:00 Opening Session 14:30-16:00 Fourth Session 9:15-10:45 Seventh Session Chair: Uri Ehrlich, Ben-Gurion University The World of Piyyut Studies in the Formulation of the Prayers, 2 Greetings: Chair: Peter Sh. -

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death Remi Jedwab and Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama⇤ April 16, 2018 Abstract We study the Black Death pogroms to shed light on the factors determining when a minority group will face persecution. In theory, negative shocks increase the likelihood that minorities are persecuted. But, as shocks become more severe, the persecution probability decreases if there are economic complementarities between majority and minority groups. The effects of shocks on persecutions are thus ambiguous. We compile city-level data on Black Death mortality and Jewish persecutions. At an aggregate level, scapegoating increases the probability of a persecution. However, cities which experienced higher plague mortality rates were less likely to persecute. Furthermore, for a given mortality shock, persecutions were less likely in cities where Jews played an important economic role and more likely in cities where people were more inclined to believe conspiracy theories that blamed the Jews for the plague. Our results have contemporary relevance given interest in the impact of economic, environmental and epidemiological shocks on conflict. JEL Codes: D74; J15; D84; N33; N43; O1; R1 Keywords: Economics of Mass Killings; Inter-Group Conflict; Minorities; Persecutions; Scapegoating; Biases; Conspiracy Theories; Complementarities; Pandemics; Cities ⇤Corresponding author: Remi Jedwab: Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, George Washington University, [email protected]. Mark Koyama: Associate -

Jewish Mysticism: Medieval Roots, Contemporary Dangers and Prospective Challenges

Jewish Mysticism: Medieval Roots, Contemporary Dangers and Prospective Challenges Lippman Bodoff Biography: Lippman Bodoff is retired as the Assistant General Counsel for ATT Technologies and Associate Editor of JUDAISM. He has published scholarly articles in JUDAISM, Midstream, Tradition, Shofar, BDD - A Journal of Torah and Scholarship, Jewish Bible Quarterly, Bible Review, and other journals. Abstract: This article traces the beginning of mysticism in main- stream Judaism to the martyrdom of the Rhineland Jews in 1096 The Edah Journal during the First Crusade, showing that (1) the tosafist view of this event was not - as generally accepted - one of approval but implicit disapproval, (2) the martyrs’ mystical impulse that embraced fervor over reason was to escape Christianity's appar- ent triumph in the world and seek refuge and life eternal with their Parent in Heaven, (3) the mystical response, elaborated into a new mythology of Creation and the nature of the Godhead, inevitably became the dominant element of Jewish piety and reli- gious thought in Christian Europe by the end of the 16th centu- ry as a defense mechanism in the face of continued persecution, and (4) this defensive psychological and cultural response must be reevaluated to determine whether it now provides more of a threat to Judaism and Jewry in the modern world than the bene- fit that it once provided to a despairing people. The Edah Journal 3:1 Edah, Inc. © 2003 Tevet 5763 Jewish Mysticism: Medieval Roots, Contemporary Dangers and Prospective Challenges Lippman Bodoff Jewish mysticism, which I define below from talmudic consider, all in Chapter 2 of Hagigah. -

University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich

Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. Winterthurerstr. 190 CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007 Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. THE BOOK OF JUBILEES: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY FROM THE FIRST GERMAN TRANSLATION OF 1850 TO THE ENOCH SEMINAR OF 2007 ISAAC W. OLIVER , University of Michigan VERONIKA BACHMANN , University of Zurich The following annotated bibliography provides summaries of the most influential scholarly works dedicated to the Book of Jubilees written between 1850 and 2006. * The year 1850 opens the period of modern research on Jubilees thanks to Dillmann’s translation of the Ethiopic text of Jubilees into German; the Enoch Seminar of 2007 represents the largest gathering of international scholars on the document in modern times. -

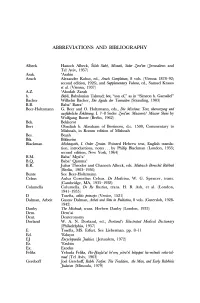

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Resume 2012-13

1 Susan L. Einbinder Oak Hall East SSHB Room 256 365 Fairfield Way U-1057 Storrs, CT 06269 860-486-9249 WORK HISTORY University of Connecticut Professor, Hebrew & Judaic Studies and Comparative Literature Dept. of Literatures, Cultures and Languages, August 2012 – Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion (Cincinnati, OH) Professor, Hebrew Literature, 2001-2012. Associate Professor,1996-2001; Assistant Professor, 1993-1996. Courses include introductory surveys and electives in medieval and modern Hebrew literature; I have covered the medieval Jewish history survey and will cover a required survey on the prophetic literature of the Bible in the spring 2011. University of Maryland, Dept. of Hebrew and East Asian Languages (College Park, MD) Visiting Lecturer, 1992-1993. Courses: Biblical Poetry; Modern Israeli Fiction; Hebrew Bible as Literature; Holocaust Fiction. New York University - General Studies Program (NY, NY), 1990-1992. Adjunct: Introd. to Ancient Western Civilization; Medieval & Renaissance Civilization; Student advisement; Higher Education Opportunities Program (HEOP) instruction. Manhattan School of Music, Humanities Department (NY, NY), 1990-1992. Adjunct: The Artist & Social Responsibility; Readings on Art and Performance Theory. Colgate University – Dept. of Philosophy & Religion (Hamilton, NY) Visiting Instructor and Chaplain to Jewish Students, 1987-88. Courses: The Bible as Literature; GNED (General Education) Introduction to Western Civilization; Israeli Fiction. EDUCATION October 1991 - Ph.D., English & Comparative Literature (M.Phil., honors, 1986; M.A., 1978) Columbia University, NY, NY. Dissertation: Mucārad&a as a Key to the Literary Unity of the Muwashshah&, supervised by Joan Ferrante (with Pierre Cachia of Columbia and Menahem Schmelzer of the Jewish Theological Seminary). May 1983 - Rabbinic ordination (M.A.H.L.,1981) Hebrew Union College - NY. -

Organization of the Talmud

Organization of the Talmud Contents The Sections and Tracts of the Talmud ................................. 2 Seder Zeraim (Seeds) ............................................ 2 Seder Moed (Festivals) ........................................... 2 Seder Nashim (Women) .......................................... 2 Seder Nezikin (Damages) ......................................... 3 Seder Kodashim (Holy Things) ...................................... 3 Seder Toharot (Purity) ........................................... 3 The rabbis of the 2nd and 3rd centuries after Christ At a certain point, probably during the 2nd cen- organized the Talmud in the form we find it to- tury after Christ, the Pharisees gave permission for day. Rabbi Jehudah the Nasi (3rd Century, presi- writing the law. Until then it was absolutely forbid- dent of the Sanhedrin) began the work of gathering den to put the oral law in writing. No sooner had together all the notes, archives, and records from this been granted that the number of manuscripts which the Talmud would be compiled. The scholars began to be very great, and when Rabbi Jehudah in Spain asserted that these notes had been in ex- had been confirmed in authority (since he enjoyed istence since schools had begun in Israel, possibly the friendship of a Roman named Antonius, who from as early as Ezra’s time. was in power in Rome), he discovered that “from the multitude of the trees the forest could not be Other Jewish scholars of that period, notably those seen.” living in France, declared that not a line was writ- ten down anywhere until this compilation began, The period of the 3rd century was very favorable for and that the writing was done from memory alone, this undertaking, because the Talmud, and its Jew- the memory of the living rabbis who were the con- ish followers, enjoyed a rest from persecutors. -

Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot

The Child at the Edge of the Cemetery: Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot MARTIN S. COHEN j i f the Mishnah wears seven veils so as modestly to hide its inmost charms from all but the most worthy of its admirers, then its sixth sec- I tion, Seder Tohorot, wears seventy of them. But to merit a peek behind those many veils requires more than the ardor or determination of even the most persistent suitor. Indeed, there is no more daunting section of the rab- binic corpus to understand—or more challenging to enjoy or more formidable to analyze . or more demoralizing to the student whose a pri- ori assumption is that the texts of classical Judaism were meant, above all, to inspire spiritual growth through their devotional study. It is no coincidence that it is rarely, if ever, studied in much depth. Indeed, other than for Tractate Niddah (which deals mostly with the laws concerning the purity status of menstruant women and the men who come into casual or intimate contact with them), there is no Talmud for any trac- tate in the seder, which detail can be interpreted to suggest that even the amoraim themselves found the material more than just slightly daunting.1 Cast in the language of science, yet clearly not founded on the kind of scien- tific principles “real” scientists bring to the informed inspection and analysis of the physical universe, the laws put forward in the sixth seder of the Mish- nah appear—at least at first blush—to have a certain dreamy arbitrariness about them able to make even the most assiduous reader despair of finding much fodder for contemplative analysis. -

Reasonable Man’

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2019 The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ Johnny Sakr The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Law Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Sakr, J. (2019). The conjecture from the universality of objectivity in jurisprudential thought: The universal presence of a ‘reasonable man’ (Master of Philosophy (School of Law)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/215 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Conjecture from the Universality of Objectivity in Jurisprudential Thought: The Universal Presence of a ‘Reasonable Man’ By Johnny Michael Sakr Submitted in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy University of Notre Dame Australia School of Law February 2019 SYNOPSIS This thesis proposes that all legal systems use objective standards as an integral part of their conceptual foundation. To demonstrate this point, this thesis will show that Jewish law, ancient Athenian law, Roman law and canon law use an objective standard like English common law’s ‘reasonable person’ to judge human behaviour. -

Final Copy of Dissertation

The Talmudic Zohar: Rabbinic Interdisciplinarity in Midrash ha-Ne’lam by Joseph Dov Rosen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair Professor Deena Aranoff Professor Niklaus Largier Summer 2017 © Joseph Dov Rosen All Rights Reserved, 2017 Abstract The Talmudic Zohar: Rabbinic Interdisciplinarity in Midrash ha-Ne’lam By Joseph Dov Rosen Joint Doctor of Philosophy in Jewish Studies with the Graduate Theological Union University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, Chair This study uncovers the heretofore ignored prominence of talmudic features in Midrash ha-Ne’lam on Genesis, the earliest stratum of the zoharic corpus. It demonstrates that Midrash ha-Ne’lam, more often thought of as a mystical midrash, incorporates both rhetorical components from the Babylonian Talmud and practices of cognitive creativity from the medieval discipline of talmudic study into its esoteric midrash. By mapping these intersections of Midrash, Talmud, and Esotericism, this dissertation introduces a new framework for studying rabbinic interdisciplinarity—the ways that different rabbinic disciplines impact and transform each other. The first half of this dissertation examines medieval and modern attempts to connect or disconnect the disciplines of talmudic study and Jewish esotericism. Spanning from Maimonides’ reliance on Islamic models of Aristotelian dialectic to conjoin Pardes (Jewish esotericism) and talmudic logic, to Gershom Scholem’s juvenile fascination with the Babylonian Talmud, to contemporary endeavours to remedy the disciplinary schisms generated by Scholem’s founding models of Kabbalah (as a form of Judaism that is in tension with “rabbinic Judaism”), these two chapters tell a series of overlapping histories of Jewish inter/disciplinary projects.