Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach Today (?)

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach today (?) Three girls in Israel were detained by the Israeli Police (2018). The girls are activists of the “Return to the Mount” (Chozrim Lahar) movement. Why were they detained? They had posted Arabic signs in the Muslim Quarter calling upon Muslims to leave the Temple Mount area until Friday night, in order to allow Jews to bring the Korban Pesach. This is the fourth time that activists of the movement will come to the Old City on Erev Pesach with goats that they plan to bring as the Korban Pesach. There is also an organization called the Temple Institute that actively is trying to bring back the Korban Pesach. It is, of course, very controversial and the issues lie at the heart of one of the most fascinating halachic debates in the past two centuries. 1 The previous mishnah was concerned with the offering of the paschal lamb when the people who were to slaughter it and/or eat it were in a state of ritual impurity. Our present mishnah is concerned with a paschal lamb which itself becomes ritually impure. Such a lamb may not be eaten. (However, we learned incidentally in our study of 5:3 that the blood that gushed from the lamb's throat at the moment of slaughter was collected in a bowl by an attendant priest and passed down the line so that it could be sprinkled on the altar). Our mishnah states that if the carcass became ritually defiled, even if the internal organs that were to be burned on the altar were intact and usable the animal was an invalid sacrifice, it could not be served at the Seder and the blood should not be sprinkled. -

As a Halakhic Argument in Rabbinic Texts

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Department of Jewish Thought, July 2006 Summary of M.A. Thesis: ]אם כן אין לדבר סוף[ ”If so, there would be no end to the matter“ As a Halakhic Argument in Rabbinic Texts Submitted to Prof. Moshe Halbertal by Nadav Berman S. This work investigates the Halakhic argument “If so, there would be no end to the matter” and its functions in the literature of the Talmudic rabbis. The work [אכאל"ס :henceforth] is divided into four main parts: 1. Preface, in which I present the academic background for exploring halakhic arguments, mainly the emergence of values as a main paradigm in the philosophy of halakha in the last decades; the significant place of halakhic arguments in the field of the halakhic decision-making [pesika]. 2. The main body of the work, in which I analyze the biblical context and halakhic ,in Talmudic sources: Mishnah (Pesachim אכאל"ס functions of the nine occurrences of 1:2; Yoma, 1:1), Tosefta (Sotah, 1:1; Sanhedrin, 9:5; Parah, 2:1; Nidah, 7:5) Jerusalem Talmud (Pesachim 27:3) Babylonian Talmud (Bava Metzi'a 28b; 60a). In order to give a concrete example, I will review two of them briefly: [חמץ] I Mishnah, tractate Pesachim: in the context of the ritual search for chamets before Passover, there is a biblical commandment (Ex. 12:19; 13:7), based on which is a rabbinic ruling that after searching for the chamets and burning it, one should not be worried by the possibility that a rat might grab a piece of bread and bring it from one location to another. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

Parashat Parah 5766

Parashat Parah 5766 This Shabbat we will read the third of the four special parshiot leading up to Pesach: Parashat Parah. In discussing the parah adumah, the Torah says, “Zot chukat haTorah, This is the law of the Torah…that they bring you a red heifer” (BaMidbar 19:2). Why does this parasha open with “zot chukat haTorah” rather than “zot chukat haparah, this is the law of the heifer,” as it does regarding the laws of the korban Pesach, “zot chukat hapesach”? The midrash explains that one who truly understand the laws of the parah adumah is as if he understands the entire Torah. In other words, although the reason behind the fact that parah adumah purifies the impure and contaminates the pure was beyond the comprehension of even Shlomo HaMelech, the wisest of men, there is nevertheless some aspect of this mitzvah that, if we understand it correctly, will enable us to understand the entire Torah. What is this chok of the Torah? The mishnah and gemara in Megillah imply that Parashat Parah must be read in Adar. Parashat Parah is thus typically read the Shabbat after Purim. Rashi writes in the name of the Yerushalmi that even though Parashat Parah should be read after Parashat HaChodesh, since chronologically Rosh Chodesh Nissan, when the Mishkan was established, precedes 2 Nissan, when the first parah adumah was slaughtered, we nevertheless read Parashat Parah earlier, during Adar. This clearly indicates some connection between the mitzvah of parah adumah and the month of Adar. What is this connection? To answer these two questions, we must understand the distinction between two types of ketivah (writing): ketivah on the material (e.g., writing on paper) and ketivah in the material (e.g., engraving). -

Mikveh and the Sanctity of Being Created Human

chapter 3 Mikveh and the Sanctity of Being Created Human Susan Grossman This paper was approved by the CJLS on September 13, 2006 by a vote of four- teen in favor, one opposed and four abstaining (14-1-4). Members voting in favor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Elliot Dorff, Aaron Mackler, Robert Harris, Robert Fine, David Wise, Daniel Nevins, Alan Lucas, Joel Roth, Myron Geller, Pamela Barmash, Gordon Tucker, Vernon Kurtz, and Susan Grossman. Members voting against: Rabbi Leonard Levy. Members abstaining: Rabbis Joseph Prouser, Loel Weiss, Paul Plotkin, and Avram Reisner. Sheilah How should we, as modern Conservative Jews, observe the laws tradition- ally referred to under the rubric Tohorat HaMishpahah (The Laws of Family Purity)?1 Teshuvah Introduction Judaism is our path to holy living, for turning the world as it is into the world as it can be. The Torah is our guide for such an ambitious aspiration, sanctified by the efforts of hundreds of generations of rabbis and their communities to 1 The author wishes to express appreciation to all the following who at different stages com- mented on this work: Dr. David Kraemer, Dr. Shaye Cohen, Dr. Seth Schwartz, Dr. Tikva Frymer-Kensky, z”l, Rabbi James Michaels, Annette Muffs Botnick, Karen Barth, and the mem- bers of the CJLS Sub-Committee on Human Sexuality. I particularly want to express my appreciation to Dr. Joel Roth. Though he never published his halakhic decisions on tohorat mishpahah (“family purity”), his lectures and teaching guided countless rabbinical students and rabbinic colleagues on this subject. In personal communication with me, he confirmed that the below psak (legal decision) and reasoning offered in his name accurately reflects his teaching. -

Organization of the Talmud

Organization of the Talmud Contents The Sections and Tracts of the Talmud ................................. 2 Seder Zeraim (Seeds) ............................................ 2 Seder Moed (Festivals) ........................................... 2 Seder Nashim (Women) .......................................... 2 Seder Nezikin (Damages) ......................................... 3 Seder Kodashim (Holy Things) ...................................... 3 Seder Toharot (Purity) ........................................... 3 The rabbis of the 2nd and 3rd centuries after Christ At a certain point, probably during the 2nd cen- organized the Talmud in the form we find it to- tury after Christ, the Pharisees gave permission for day. Rabbi Jehudah the Nasi (3rd Century, presi- writing the law. Until then it was absolutely forbid- dent of the Sanhedrin) began the work of gathering den to put the oral law in writing. No sooner had together all the notes, archives, and records from this been granted that the number of manuscripts which the Talmud would be compiled. The scholars began to be very great, and when Rabbi Jehudah in Spain asserted that these notes had been in ex- had been confirmed in authority (since he enjoyed istence since schools had begun in Israel, possibly the friendship of a Roman named Antonius, who from as early as Ezra’s time. was in power in Rome), he discovered that “from the multitude of the trees the forest could not be Other Jewish scholars of that period, notably those seen.” living in France, declared that not a line was writ- ten down anywhere until this compilation began, The period of the 3rd century was very favorable for and that the writing was done from memory alone, this undertaking, because the Talmud, and its Jew- the memory of the living rabbis who were the con- ish followers, enjoyed a rest from persecutors. -

URJ Online Communications Master Word List 1 MASTER

URJ Online Communications Master Word List MASTER WORD LIST, Ashamnu (prayer) REFORMJUDAISM.org Ashkenazi, Ashkenazim Revised 02-12-15 Ashkenazic Ashrei (prayer) Acharei Mot (parashah) atzei chayim acknowledgment atzeret Adar (month) aufruf Adar I (month) Av (month) Adar II (month) Avadim (tractate) “Adir Hu” (song) avanah Adon Olam aveirah Adonai Avinu Malkeinu (prayer) Adonai Melech Avinu shebashamayim Adonai Tz’vaot (the God of heaven’s hosts [Rev. avodah Plaut translation] Avodah Zarah (tractate) afikoman avon aggadah, aggadot Avot (tractate) aggadic Avot D’Rabbi Natan (tractate) agunah Avot V’Imahot (prayer) ahavah ayin (letter) Ahavah Rabbah (prayer) Ahavat Olam (prayer) baal korei Akeidah Baal Shem Tov Akiva baal t’shuvah Al Cheit (prayer) Babylonian Empire aleph (letter) Babylonian exile alef-bet Babylonian Talmud Aleinu (prayer) baby naming, baby-naming ceremony Al HaNisim (prayer) badchan aliyah, aliyot Balak (parashah) A.M. (SMALL CAPS) bal tashchit am baraita, baraitot Amidah Bar’chu Amora, Amoraim bareich amoraic Bar Kochba am s’gulah bar mitzvah Am Yisrael Baruch atah Adonai, Eloheinu Melech haolam, Angel of Death asher kid’shanu b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu Ani Maamin (prayer) Baruch She-Amar (prayer) aninut Baruch Shem anti-Semitism Baruch SheNatan (prayer) Arachin (tractate) bashert, basherte aravah bat arbaah minim bat mitzvah arba kanfot Bava Batra (tractate) Arba Parashiyot Bava Kama (tractate) ark (synagogue) Bava M’tzia (tractate) ark (Noah’s) Bavli Ark of the Covenant, the Ark bayit (house) Aron HaB’rit Bayit (the Temple) -

English Mishnah Chart

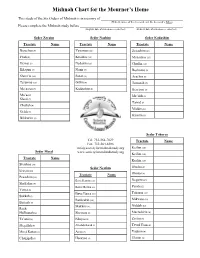

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Guide to Hebrew Transliteration and Rabbinic Texts

Guide to using Rabbinic texts: Transliteration issues: Hebrew has a different phonetic structure from English, and there is no universally accepted transliteration system. Therefore, the same title or word might show up in English works with diverse spellings. Here are a few things you can look for. Consonants ß The Hebrew letter b is usually an English B, but under some circumstances it is pronounced as a V. In those cases, it can be transliterated as either b, b, or v. (In German, it might even show up as a w.) ß Hebrew w can show up as either a v or a w. ß Hebrew x is an aspirated h sound, and is correctly transliterated as a h 9 (with a dot underneath). Ashkenazic Jews pronounce it as a gutteral, like the soft k (see below), and so it is often transliterated as a kh or ch. ß The Hebrew y, which is a Y consonant, might be transliterated as i or j (especially in German works). ß Similarly, the letter k is usually a simple K, but under some circumstances it is a guttural (Scottish/German) ch or kh sound, and is transliterated accordingly. ß Hebrew p can be either a P or F sound, depending on certain grammatical rules. In the latter case, it can be written as a p, p, f or ph. ß The Hebrew c is an emphatic S sound with no real equivalent in English. The correct transliteration is s,9 but Ashkenazic Jews generally pronounce it as a TZ sound, so that it will be transliterated as z, tz, ts, c or.ç. -

Of the Mishnah, Bavli & Yerushalmi

0 Learning at SVARA SVARA’s learning happens in the bet midrash, a space for study partners (chevrutas) to build a relationship with the Talmud text, with one another, and with the tradition—all in community and a queer-normative, loving culture. The learning is rigorous, yet the bet midrash environment is warm and supportive. Learning at SVARA focuses on skill-building (learning how to learn), foregrounding the radical roots of the Jewish tradition, empowering learners to become “players” in it, cultivating Talmud study as a spiritual practice, and with the ultimate goal of nurturing human beings shaped by one of the central spiritual, moral, and intellectual technologies of our tradition: Talmud Torah (the study of Torah). The SVARA method is a simple, step-by-step process in which the teacher is always an authentic co-learner with their students, teaching the Talmud not so much as a normative document prescribing specific behaviors, but as a formative document, shaping us into a certain kind of human being. We believe the Talmud itself is a handbook for how to, sometimes even radically, upgrade our tradition when it no longer functions to create the most liberatory world possible. All SVARA learning begins with the CRASH Talk. Here we lay out our philosophy of the Talmud and the rabbinic revolution that gave rise to it—along with important vocabulary and concepts for anyone learning Jewish texts. This talk is both an overview of the ultimate goals of the Jewish enterprise, as well as a crash course in halachic (Jewish legal) jurisprudence. Beyond its application to Judaism, CRASH Theory is a simple but elegant model of how all change happens—whether societal, religious, organizational, or personal. -

Scripture, Interpretation, Or Authority?

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) 320 Thomas Kazen Scripture, Interpretation, or Authority? Motives and Arguments in Jesus’ Halakic Conflicts Mohr Siebeck Thomas Kazen, born 1960; since 1990 Minister in the Uniting Church in Sweden (pre- viously Swedish Covenant Church); 2002 ThD in New Testament Exegesis (Uppsala); since 2010 Professor of Biblical Studies of Stockholm School of Theology. ISBN 978-3-16-152893-4 ISSN 0512-1604 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliogra- phie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2013 by Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Gulde-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buch binderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. In memory of my father Roland Kazen 1936–2009 and a vision of restoration for the marginalized Preface A book on motives and arguments in Jesus’ conflicts with his contempo- raries about various halakic issues is not really too much of a departure in view of my earlier studies on purity and impurity. In my dissertation (Je- sus and Purity Halakhah, 2002; corrected reprint edition 2010; see also Issues of Impurity in Early Judaism, 2010) I asked questions not only about what Jesus did or did not do, but also about his attitudes. -

Judges) “In All Your Gates” That They Are to Judge the People with Righteous Judgment

בייה PORTION DATE HEB DATE TORAH NEVIIM RENEWED Shoftim 18 Aug. 2018 7 Elul 5778 Deut. 16:18-21:9 Isa. 51:12-52:12 John 14:9-20 This week’s Torah portion starts with the qualification of shoftim (judges) “in all your gates” that they are to judge the people with righteous judgment. The Torah then describes how they are to judge against the accused. The Midrash questions the eligibility of judges. The immediate family of litigants are disqualified to judge as well as they are ineligible to testify as said, “The ahvot (fathers) shall not be put to death for the children, neither shall the children be put to death for the ahvot.” (Deut. 24:16) The Gemara interprets: fathers shall not be executed because of the testimony of sons, and vice versa.1 Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel (10 BCE-70 CE) said: Do not make light of justice, for it is one of the three legs of the world: justice, truth, and on peace. Therefore, we are to be mindful of not perverting justice as “you can cause the world to shake2 for it (justice) is one of the legs of Hashem’s Throne of Glory. “Righteousness and justice are the foundation of Your throne.” (Psa 85:15) The Proverbs 6:6-8 says, “Go to the ant, you lazy one; consider her halachot, and be wise: They have no guide, overseer, or ruler, yet she; Provides her food in the and gathers her food in the harvest.” The sages teach the ants has three stories in its home.