As a Halakhic Argument in Rabbinic Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach Today (?)

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach today (?) Three girls in Israel were detained by the Israeli Police (2018). The girls are activists of the “Return to the Mount” (Chozrim Lahar) movement. Why were they detained? They had posted Arabic signs in the Muslim Quarter calling upon Muslims to leave the Temple Mount area until Friday night, in order to allow Jews to bring the Korban Pesach. This is the fourth time that activists of the movement will come to the Old City on Erev Pesach with goats that they plan to bring as the Korban Pesach. There is also an organization called the Temple Institute that actively is trying to bring back the Korban Pesach. It is, of course, very controversial and the issues lie at the heart of one of the most fascinating halachic debates in the past two centuries. 1 The previous mishnah was concerned with the offering of the paschal lamb when the people who were to slaughter it and/or eat it were in a state of ritual impurity. Our present mishnah is concerned with a paschal lamb which itself becomes ritually impure. Such a lamb may not be eaten. (However, we learned incidentally in our study of 5:3 that the blood that gushed from the lamb's throat at the moment of slaughter was collected in a bowl by an attendant priest and passed down the line so that it could be sprinkled on the altar). Our mishnah states that if the carcass became ritually defiled, even if the internal organs that were to be burned on the altar were intact and usable the animal was an invalid sacrifice, it could not be served at the Seder and the blood should not be sprinkled. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

Parashat Parah 5766

Parashat Parah 5766 This Shabbat we will read the third of the four special parshiot leading up to Pesach: Parashat Parah. In discussing the parah adumah, the Torah says, “Zot chukat haTorah, This is the law of the Torah…that they bring you a red heifer” (BaMidbar 19:2). Why does this parasha open with “zot chukat haTorah” rather than “zot chukat haparah, this is the law of the heifer,” as it does regarding the laws of the korban Pesach, “zot chukat hapesach”? The midrash explains that one who truly understand the laws of the parah adumah is as if he understands the entire Torah. In other words, although the reason behind the fact that parah adumah purifies the impure and contaminates the pure was beyond the comprehension of even Shlomo HaMelech, the wisest of men, there is nevertheless some aspect of this mitzvah that, if we understand it correctly, will enable us to understand the entire Torah. What is this chok of the Torah? The mishnah and gemara in Megillah imply that Parashat Parah must be read in Adar. Parashat Parah is thus typically read the Shabbat after Purim. Rashi writes in the name of the Yerushalmi that even though Parashat Parah should be read after Parashat HaChodesh, since chronologically Rosh Chodesh Nissan, when the Mishkan was established, precedes 2 Nissan, when the first parah adumah was slaughtered, we nevertheless read Parashat Parah earlier, during Adar. This clearly indicates some connection between the mitzvah of parah adumah and the month of Adar. What is this connection? To answer these two questions, we must understand the distinction between two types of ketivah (writing): ketivah on the material (e.g., writing on paper) and ketivah in the material (e.g., engraving). -

Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot

The Child at the Edge of the Cemetery: Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot MARTIN S. COHEN j i f the Mishnah wears seven veils so as modestly to hide its inmost charms from all but the most worthy of its admirers, then its sixth sec- I tion, Seder Tohorot, wears seventy of them. But to merit a peek behind those many veils requires more than the ardor or determination of even the most persistent suitor. Indeed, there is no more daunting section of the rab- binic corpus to understand—or more challenging to enjoy or more formidable to analyze . or more demoralizing to the student whose a pri- ori assumption is that the texts of classical Judaism were meant, above all, to inspire spiritual growth through their devotional study. It is no coincidence that it is rarely, if ever, studied in much depth. Indeed, other than for Tractate Niddah (which deals mostly with the laws concerning the purity status of menstruant women and the men who come into casual or intimate contact with them), there is no Talmud for any trac- tate in the seder, which detail can be interpreted to suggest that even the amoraim themselves found the material more than just slightly daunting.1 Cast in the language of science, yet clearly not founded on the kind of scien- tific principles “real” scientists bring to the informed inspection and analysis of the physical universe, the laws put forward in the sixth seder of the Mish- nah appear—at least at first blush—to have a certain dreamy arbitrariness about them able to make even the most assiduous reader despair of finding much fodder for contemplative analysis. -

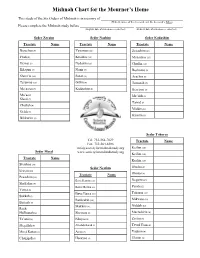

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Of the Mishnah, Bavli & Yerushalmi

0 Learning at SVARA SVARA’s learning happens in the bet midrash, a space for study partners (chevrutas) to build a relationship with the Talmud text, with one another, and with the tradition—all in community and a queer-normative, loving culture. The learning is rigorous, yet the bet midrash environment is warm and supportive. Learning at SVARA focuses on skill-building (learning how to learn), foregrounding the radical roots of the Jewish tradition, empowering learners to become “players” in it, cultivating Talmud study as a spiritual practice, and with the ultimate goal of nurturing human beings shaped by one of the central spiritual, moral, and intellectual technologies of our tradition: Talmud Torah (the study of Torah). The SVARA method is a simple, step-by-step process in which the teacher is always an authentic co-learner with their students, teaching the Talmud not so much as a normative document prescribing specific behaviors, but as a formative document, shaping us into a certain kind of human being. We believe the Talmud itself is a handbook for how to, sometimes even radically, upgrade our tradition when it no longer functions to create the most liberatory world possible. All SVARA learning begins with the CRASH Talk. Here we lay out our philosophy of the Talmud and the rabbinic revolution that gave rise to it—along with important vocabulary and concepts for anyone learning Jewish texts. This talk is both an overview of the ultimate goals of the Jewish enterprise, as well as a crash course in halachic (Jewish legal) jurisprudence. Beyond its application to Judaism, CRASH Theory is a simple but elegant model of how all change happens—whether societal, religious, organizational, or personal. -

SYNOPSIS the Mishnah and Tosefta Are Two Related Works of Legal

SYNOPSIS The Mishnah and Tosefta are two related works of legal discourse produced by Jewish sages in Late Roman Palestine. In these works, sages also appear as primary shapers of Jewish law. They are portrayed not only as individuals but also as “the SAGES,” a literary construct that is fleshed out in the context of numerous face-to-face legal disputes with individual sages. Although the historical accuracy of this portrait cannot be verified, it reveals the perceptions or wishes of the Mishnah’s and Tosefta’s redactors about the functioning of authority in the circles. An initial analysis of fourteen parallel Mishnah/Tosefta passages reveals that the authority of the Mishnah’s SAGES is unquestioned while the Tosefta’s SAGES are willing at times to engage in rational argumentation. In one passage, the Tosefta’s SAGES are shown to have ruled hastily and incorrectly on certain legal issues. A broader survey reveals that the Mishnah also contains a modest number of disputes in which the apparently sui generis authority of the SAGES is compromised by their participation in rational argumentation or by literary devices that reveal an occasional weakness of judgment. Since the SAGES are occasionally in error, they are not portrayed in entirely ideal terms. The Tosefta’s literary construct of the SAGES differs in one important respect from the Mishnah’s. In twenty-one passages, the Tosefta describes a later sage reviewing early disputes. Ten of these reviews involve the SAGES. In each of these, the later sage subjects the dispute to further analysis that accords the SAGES’ opinion no more a priori weight than the opinion of individual sages. -

Shemini- Parah 3-22-14

בס״ד March 22-28 2014 | Adar II 20-26 5774 ARTSCROLL Chumash Volume 15, Issue 26 Parsha : pg. 588 QJC WEEKLY Maftir : pg. 838 Parshas Shemini | Parah Haftorah : pg. 1216 Queens Jewish Center SHABBOS SCHEDULE WEEKDAY SCHEDULE 66-05 108 Street SERVICES SERVICES Forest Hills, NY 11375 Hashkoma Service .................. 7:45 am Shacharis Shacharis - Bais Hamedrash ... 8:30 am Sun ............................7:15 & 8:30 am Website: www.MyQJC.org Shacharis - Main Shul ............. 9:00 am Mon ................................ 6:20 & 7:30 am Ph: (718) 459-8432 KIDS - 3rd floor Tue, Wed & Fri ..........6:30 & 7:30 am Office Email: [email protected] Playroom ................................ 9:30 am R’ Hopkovitz Email: [email protected] Shul School ........................... 10:00 am Mincha/Maariv .........................6:55 pm Mincha .................................... 6:20 pm CLASSES followed by a Special Seudah Shlishis/ DAF YOMI SHIUR - Rabbi Bezalel Ostrow Siyum Mishnayos . Speaker: Uri Burger Coffee & Cake is served Shabbos ends ......................... 8:00 pm SUN ........................................ 9:30 am MON - FRI .............................. 8:45 am CLASSES MONDAY Mishna Brurah - Rabbi Leonard Levy .....7:30 am Famous Teshuvos of Harav Ovadia Yosef Talmud - Rabbi Bezalel Ostrow (BH) .10:30 am If you would like to receive Rabbi Simcha Hopkovitz ........7:45 pm Daf Yomi - Rabbi Shmuel Gold ..............5:20 pm weekly emails from the WEDNESDAY Basic Chumash - Mr. Mendel Weiss .......5:20 pm Queens Jewish Center, Book of Samuel -

Rereading the Mishnah

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Martin Hengel and Peter Schäfer 109 Judith Hauptman Rereading the Mishnah A New Approach to Ancient Jewish Texts Mohr Siebeck JUDITH HAUPTMAN: born 1943; BA in Economics at Barnard College (Columbia Univer- sity); BHL, MA, PhD in Talmud and Rabbinics at Jewish Theological Seminary; is currently E. Billy Ivry Professor of Talmud and Rabbinic Culture, Jewish Theological Seminary, NY. ISBN 3-16-148713-3 ISSN 0721-8753 (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; de- tailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2005 by Judith Hauptman / Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Guide-Druck in Tiibingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. •mm i^DH tn In memory of my brother, Philip Jonathan Hauptman, a heroic physician, who died on Rosh Hodesh Nisan 5765 Contents Preface IX Notes to the Reader XII Abbreviations XIII Chapter 1: Rethinking the Relationship between the Mishnah and the Tosefta 1 A. Two Illustrative Sets of Texts 3 B. Theories of the Tosefta's Origins 14 C. New Model 17 D. Challenges and Responses 25 E. This Book 29 Chapter 2: The Tosefta as a Commentary on an Early Mishnah 31 A. -

Beginners Guide for the Major Jewish Texts: Torah, Mishnah, Talmud

August 2001, Av 5761 The World Union of Jewish Students (WUJS) 9 Alkalai St., POB 4498 Jerusalem, 91045, Israel Tel: +972 2 561 0133 Fax: +972 2 561 0741 E-mail: [email protected] Web-site: www.wujs.org.il Originally produced by AJ6 (UK) ©1998 This edition ©2001 WUJS – All Rights Reserved The Guide To Texts Published and produced by WUJS, the World Union of Jewish Students. From the Chairperson Dear Reader Welcome to the Guide to Texts. This introductory guide to Jewish texts is written for students who want to know the difference between the Midrash and Mishna, Shulchan Aruch and Kitzur Shulchan Aruch. By taking a systematic approach to the obvious questions that students might ask, the Guide to Texts hopes to quickly and clearly give students the information they are after. Unfortunately, many Jewish students feel alienated from traditional texts due to unfamiliarity and a feeling that Jewish sources don’t ‘belong’ to them. We feel that Jewish texts ought to be accessible to all of us. We ought to be able to talk about them, to grapple with them, and to engage with them. Jewish texts are our heritage, and we can’t afford to give it up. Jewish leaders ought to have certain skills, and ethical values, but they also need a certain commitment to obtaining the knowledge necessary to ensure that they aren’t just leaders, but Jewish leaders. This Guide will ensure that this is the case. Learning, and then leading, are the keys to Jewish student leadership. Lead on! Peleg Reshef WUJS Chairperson How to Use The Guide to Jewish Texts Many Jewish students, and even Jewish student leaders, don’t know the basics of Judaism and Jewish texts. -

Pesachim - Simanim ףד י ח – Daf 18 1

Pesachim - Simanim ףד י ח – Daf 18 1. A cow drinking mei chatas Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak brought a Mishnah from Parah to prove that when Rebbe Yehuda retracted his ruling and said mashkin can only be metamei mid’Rabbanon, it was not just with regard to keilim but also to .if a cow drank mei chatas its flesh is tamei – הרפ התתשש מ י תאטח הרשב אמט ,food. The Mishnah stated the water is nullified in the cow’s intestines and lost its capacity to be – לטב ו עמב י ה ,Rebbe Yehudah said metamei, therefore, the flesh, which is considered food, is tahor. Rashi explains that since the water becomes unfit for purification within the cow’s innards, it loses its capacity to be metamei. If Rebbe Yehudah held that mashkin is metamei mid’Oraysa, then the water should be metamei regardless if it is fit for mei chatas. The Gemara says that this is not a proof that Rebbe Yehuda holds mashkin are only metamei food means that it became nullified from being metamei לטב ו עמב י ה mid’Rabbanon, because it may be that , האמוט הלק meaning, that it cannot make a person or vessels tamei, but it still can be metamei , האמוט מח ו הרומ Really Rebbe Yehudah – על ו םל לטב ו מב י הע ירמגל ,such as food, and in this case flesh. Rav Ashi answered because once – שמ ו ם הד ו ה היל קשמ ה רס ו ח ,holds that the water is completely nullified in the cow’s intestines inside the cow the water is a putrid beverage, which is entirely precluded from tumah. -

Divrei Hayamim 1 11-20 Ketuvim Simchi Machshirim 4-6 Mishnah Sokol Tohorot 1-3 Mishnah Soyfer Vayechi Torah Spanganthal Tzfaniah Navi J

Abergel Miketz Torah Abraizov Devirim Torah Addi Acahrei Mos Torah Adler Tehillim 30-40 Ketuvim Akselrod Shemos Torah G.Alster Amos Navi Apter Balak Torah Aron Peah 1-4 Mishnah Ashkanazy Shlach Torah Ashkenas Peah 5-9 Mishnah Avital Terumot 1-5 Mishnah J. Bacon Negaim 1-5 Mishnah S. Bacon Negaim 6-10 Mishnah Baker Maaser Sheni Mishnah Bannett yevamot 1-6 Mishnah Barach Ki Tavo Torah Baron Bo Torah Barth D Shmini Torah Barth Bikkurim Mishnah Basis Korach Torah H.Beckoff Ekev Torah N.Beckoff Besah Mishnah L.Bien Samuel 2 14-24 Navi M. Bender Emor Torah Berger Pinchas Torah M. Berkowitz Challah Mishnah M. Berman Beshalach Torah A. Bichler Micha Navi Blatt Kedushin Mishnah A.Bloom Yirmyahu 1-10 Navi J. Bloom Moed Katan Mishnah Bluman Yevamot 7-11 Mishnah Bodner Shabbos 1-4 Mishnah Boussi Yirmyahu 11-20 Navi A.Bowski Tehillim 1-10 Ketuvim L.Bowski Samuel 1 1-10 Navi Brandes Ovadiah Navi Brandstatter Shabbos 9-13 Mishnah Bravman Taanit Mishnah Breban Rosh Hashana Mishnah Brodsky Chukat Torah Brook Vayelech Torah Caplan Reeh Torah Chait Behar Torah Cheifetz Vayechi Torah Chernela Vayikra Torah Cochin Tehillim 20-30 Ketuvim J. Cohen Yhoshua 1-12 Navi M.Cohen Noach Torah Eis Peah 5-9 Mishnah Eisenstadter Toldot Torah Epstein Lech Lecha Torah Felner Nitzavim Torah Fialkoff Vayelech Torah Fischer Nazir Mishnah Fishman Challah Mishnah Fishweicher Maasarot Mishnah Moshe Fishweicher Matot Torah Fleisher Vayetzei Torah Fleyshmakher Ki Tetzei Torah Fogelman Chagiga Mishnah Fox Esther Navi Frank shabbos 8-12 Mishnah D. Friedman Keilim Mishnah Y.Friedman Gitten1-5 Mishnah Michael Friedman Shoftim Torah Mikki Friedman Shoftim 1-12 Navi Frohlich Yoma 1-4 Mishnah Gabovich Tehillim 31-40 Ketuvim Galitsky Tehillim 41-50 Ketuvim Gandelman Bamidbar Torah Gans Yevamot 12-16 Mishnah Garber Terumot 6-11 Mishnah Garfunkel Samuel 1 1-12 Navi Gelerter Behar Ketuvim Gensler Terumah Torah Gerber Shoftim 12-21 Navi Gershon Ketuvos 1-7 Mishnah Gerstley Pesachim 1-4 Mishnah Gitlin Vayeyra Torah Glass Sukkah Mishnah Glassman tehillim 51-60 Torah H.Gold Noach Ketuvim A.