Parah Chapter 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach Today (?)

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach today (?) Three girls in Israel were detained by the Israeli Police (2018). The girls are activists of the “Return to the Mount” (Chozrim Lahar) movement. Why were they detained? They had posted Arabic signs in the Muslim Quarter calling upon Muslims to leave the Temple Mount area until Friday night, in order to allow Jews to bring the Korban Pesach. This is the fourth time that activists of the movement will come to the Old City on Erev Pesach with goats that they plan to bring as the Korban Pesach. There is also an organization called the Temple Institute that actively is trying to bring back the Korban Pesach. It is, of course, very controversial and the issues lie at the heart of one of the most fascinating halachic debates in the past two centuries. 1 The previous mishnah was concerned with the offering of the paschal lamb when the people who were to slaughter it and/or eat it were in a state of ritual impurity. Our present mishnah is concerned with a paschal lamb which itself becomes ritually impure. Such a lamb may not be eaten. (However, we learned incidentally in our study of 5:3 that the blood that gushed from the lamb's throat at the moment of slaughter was collected in a bowl by an attendant priest and passed down the line so that it could be sprinkled on the altar). Our mishnah states that if the carcass became ritually defiled, even if the internal organs that were to be burned on the altar were intact and usable the animal was an invalid sacrifice, it could not be served at the Seder and the blood should not be sprinkled. -

As a Halakhic Argument in Rabbinic Texts

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Department of Jewish Thought, July 2006 Summary of M.A. Thesis: ]אם כן אין לדבר סוף[ ”If so, there would be no end to the matter“ As a Halakhic Argument in Rabbinic Texts Submitted to Prof. Moshe Halbertal by Nadav Berman S. This work investigates the Halakhic argument “If so, there would be no end to the matter” and its functions in the literature of the Talmudic rabbis. The work [אכאל"ס :henceforth] is divided into four main parts: 1. Preface, in which I present the academic background for exploring halakhic arguments, mainly the emergence of values as a main paradigm in the philosophy of halakha in the last decades; the significant place of halakhic arguments in the field of the halakhic decision-making [pesika]. 2. The main body of the work, in which I analyze the biblical context and halakhic ,in Talmudic sources: Mishnah (Pesachim אכאל"ס functions of the nine occurrences of 1:2; Yoma, 1:1), Tosefta (Sotah, 1:1; Sanhedrin, 9:5; Parah, 2:1; Nidah, 7:5) Jerusalem Talmud (Pesachim 27:3) Babylonian Talmud (Bava Metzi'a 28b; 60a). In order to give a concrete example, I will review two of them briefly: [חמץ] I Mishnah, tractate Pesachim: in the context of the ritual search for chamets before Passover, there is a biblical commandment (Ex. 12:19; 13:7), based on which is a rabbinic ruling that after searching for the chamets and burning it, one should not be worried by the possibility that a rat might grab a piece of bread and bring it from one location to another. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

Parashat Parah 5766

Parashat Parah 5766 This Shabbat we will read the third of the four special parshiot leading up to Pesach: Parashat Parah. In discussing the parah adumah, the Torah says, “Zot chukat haTorah, This is the law of the Torah…that they bring you a red heifer” (BaMidbar 19:2). Why does this parasha open with “zot chukat haTorah” rather than “zot chukat haparah, this is the law of the heifer,” as it does regarding the laws of the korban Pesach, “zot chukat hapesach”? The midrash explains that one who truly understand the laws of the parah adumah is as if he understands the entire Torah. In other words, although the reason behind the fact that parah adumah purifies the impure and contaminates the pure was beyond the comprehension of even Shlomo HaMelech, the wisest of men, there is nevertheless some aspect of this mitzvah that, if we understand it correctly, will enable us to understand the entire Torah. What is this chok of the Torah? The mishnah and gemara in Megillah imply that Parashat Parah must be read in Adar. Parashat Parah is thus typically read the Shabbat after Purim. Rashi writes in the name of the Yerushalmi that even though Parashat Parah should be read after Parashat HaChodesh, since chronologically Rosh Chodesh Nissan, when the Mishkan was established, precedes 2 Nissan, when the first parah adumah was slaughtered, we nevertheless read Parashat Parah earlier, during Adar. This clearly indicates some connection between the mitzvah of parah adumah and the month of Adar. What is this connection? To answer these two questions, we must understand the distinction between two types of ketivah (writing): ketivah on the material (e.g., writing on paper) and ketivah in the material (e.g., engraving). -

Miracles in Greco-Roman Antiquity: a Sourcebook/Wendy Cotter

MIRACLES IN GRECO-ROMAN ANTIQUITY Miracles in Greco-Roman Antiquity is a sourcebook which presents a concise selection of key miracle stories from the Greco- Roman world, together with contextualizing texts from ancient authors as well as footnotes and commentary by the author herself. The sourcebook is organized into four parts that deal with the main miracle story types and magic: Gods and Heroes who Heal and Raise the Dead, Exorcists and Exorcisms, Gods and Heroes who Control Nature, and Magic and Miracle. Two appendixes add richness to the contextualization of the collection: Diseases and Doctors features ancient authors’ medical diagnoses, prognoses and treatments for the most common diseases cured in healing miracles; Jesus, Torah and Miracles selects pertinent texts from the Old Testament and Mishnah necessary for the understanding of certain Jesus miracles. This collection of texts not only provides evidence of the types of miracle stories most popular in the Greco-Roman world, but even more importantly assists in their interpretation. The contextualizing texts enable the student to reconstruct a set of meanings available to the ordinary Greco-Roman, and to study and compare the forms of miracle narrative across the whole spectrum of antique culture. Wendy Cotter C.S.J. is Associate Professor of Scripture at Loyola University, Chicago. MIRACLES IN GRECO-ROMAN ANTIQUITY A sourcebook Wendy Cotter, C.S.J. First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. -

Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot

The Child at the Edge of the Cemetery: Portraiture and Symbolism in Seder Tohorot MARTIN S. COHEN j i f the Mishnah wears seven veils so as modestly to hide its inmost charms from all but the most worthy of its admirers, then its sixth sec- I tion, Seder Tohorot, wears seventy of them. But to merit a peek behind those many veils requires more than the ardor or determination of even the most persistent suitor. Indeed, there is no more daunting section of the rab- binic corpus to understand—or more challenging to enjoy or more formidable to analyze . or more demoralizing to the student whose a pri- ori assumption is that the texts of classical Judaism were meant, above all, to inspire spiritual growth through their devotional study. It is no coincidence that it is rarely, if ever, studied in much depth. Indeed, other than for Tractate Niddah (which deals mostly with the laws concerning the purity status of menstruant women and the men who come into casual or intimate contact with them), there is no Talmud for any trac- tate in the seder, which detail can be interpreted to suggest that even the amoraim themselves found the material more than just slightly daunting.1 Cast in the language of science, yet clearly not founded on the kind of scien- tific principles “real” scientists bring to the informed inspection and analysis of the physical universe, the laws put forward in the sixth seder of the Mish- nah appear—at least at first blush—to have a certain dreamy arbitrariness about them able to make even the most assiduous reader despair of finding much fodder for contemplative analysis. -

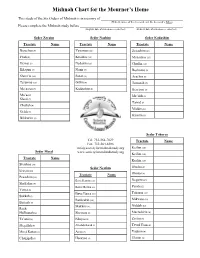

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Of the Mishnah, Bavli & Yerushalmi

0 Learning at SVARA SVARA’s learning happens in the bet midrash, a space for study partners (chevrutas) to build a relationship with the Talmud text, with one another, and with the tradition—all in community and a queer-normative, loving culture. The learning is rigorous, yet the bet midrash environment is warm and supportive. Learning at SVARA focuses on skill-building (learning how to learn), foregrounding the radical roots of the Jewish tradition, empowering learners to become “players” in it, cultivating Talmud study as a spiritual practice, and with the ultimate goal of nurturing human beings shaped by one of the central spiritual, moral, and intellectual technologies of our tradition: Talmud Torah (the study of Torah). The SVARA method is a simple, step-by-step process in which the teacher is always an authentic co-learner with their students, teaching the Talmud not so much as a normative document prescribing specific behaviors, but as a formative document, shaping us into a certain kind of human being. We believe the Talmud itself is a handbook for how to, sometimes even radically, upgrade our tradition when it no longer functions to create the most liberatory world possible. All SVARA learning begins with the CRASH Talk. Here we lay out our philosophy of the Talmud and the rabbinic revolution that gave rise to it—along with important vocabulary and concepts for anyone learning Jewish texts. This talk is both an overview of the ultimate goals of the Jewish enterprise, as well as a crash course in halachic (Jewish legal) jurisprudence. Beyond its application to Judaism, CRASH Theory is a simple but elegant model of how all change happens—whether societal, religious, organizational, or personal. -

The Truth About the Talmud

The Talmud: Judaism's holiest book documented and exposed 236/08/Thursday 08h16 The Truth about the Talmud A documented exposé of Jewish Supremacist hate literature Copyright ©2000 by Michael A. Hoffman II and Alan R. Critchley All Rights Reserved Independent History & Research, Box 849, Coeur d'Alene, Idaho 83816 http://www.hoffman-info.com/talmudtruth.html Introduction The Talmud is Judaism's holiest book (actually a collection of books). Its authority takes precedence over the Old Testament in Judaism. Evidence of this may be found in the Talmud itself, Erubin 21b (Soncino edition): "My son, be more careful in the observance of the words of the Scribes than in the words of the Torah (Old Testament)." The supremacy of the Talmud over the Bible in the Israeli state may also be seen in the case of the black Ethiopian Jews. Ethiopians are very knowledgeable of the Old Testament. However, their religion is so ancient it pre-dates the Scribes' Talmud, of which the Ethiopians have no knowledge. According to the N.Y. Times of Sept. 29, 1992, p.4: "The problem is that Ethiopian Jewish tradition goes no further than the Bible or Torah; the later Talmud and other commentaries that form the basis of modern traditions never came their way." Because they are not traffickers in Talmudic tradition, the black Ethiopian Jews are discriminated against and have been forbidden by the Zionists to perform marriages, funerals and other services in the Israeli state. Rabbi Joseph D. Soloveitchik is regarded as one of the most influential rabbis of the 20th century, the "unchallenged leader" of Orthodox Judaism and the top international authority on halakha (Jewish religious law). -

Vayeishev 5758 Volume V Number 12

Tazria 5779 Volume XXVI Number 29 Toras Aish Thoughts From Across the Torah Spectrum 4. Sforno says that the woman has been RABBI LORD JONATHAN SACKS intensely focused on the physical processes Covenant & Conversation accompanying childbirth. She needs both time and the t the start of this parsha is a cluster of laws that bringing of an offering to rededicate her thoughts to challenged and puzzled the commentators. They God and matters of the spirit. Aconcern a woman who has just given birth. If she 5. Rabbi Meir Simcha of Dvinsk says that the gives birth to a son, she is "unclean for seven days, just burnt offering is like an olat re'iya, an offering brought as she is unclean during her monthly period." She must when appearing at the Temple on festivals, following then wait for a further thirty-three days before coming the injunction, "Do not appear before Me empty- into contact with holy objects or appearing at the handed" (Ex. 23:15). The woman celebrates her ability Temple. If she gives birth to a girl, both time periods are to appear before God at the Temple. doubled: she is unclean for two weeks and must wait a Without displacing any of these ideas, we might further sixty-six days. She then has to bring two however suggest another set of perspectives. The first offerings: "When her purification period for a son or a is about the fundamental concepts that dominate this daughter is complete, she shall bring to the Priest, to section of Leviticus, the words tamei and tahor, the Communion Tent entrance, a yearling sheep for a normally translated as (ritually) "unclean/clean," or burnt offering, and a young common dove, or a turtle "defiled/pure." It is important to note that these words dove for a sin offering. -

The Tikvah Center for Law & Jewish Civilization

THE TIKVAH CENTER FOR LAW & JEWISH CIVILIZATION Professor J.H.H. Weiler Director of The Tikvah Center Tikvah Working Paper 01/10 Aharon Shemesh A Nazirite for Rent NYU School of Law New York, NY 10011 The Tikvah Center Working Paper Series can be found at http://www.nyutikvah.org/publications.html All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author. ISSN 2160‐8229 (print) ISSN 2160‐8253 (online) Copy Editor: Danielle Leeds Kim © Aharon Shemesh 2010 New York University School of Law New York, NY 10011 USA Publications in the Series should be cited as: AUTHOR, TITLE, TIKVAH CENTER WORKING PAPER NO./YEAR [URL] A NAZIRITE FOR RENT By Aharon Shemesh Abstract This article argues that a unique socio-religious phenomenon of professional nazirites has existed towards the end of the second Temple period. Alongside those who became nazirites out of religious piety, there were also people who took upon themselves the vow of nazirhood in order to make a living off the donations of rich patrons. Some of the early Rabbis opposed this phenomenon and introduced new laws that made this type of nazirhood impractical. This is thus an interesting test case for the complicated dynamic between popular religious practices and beliefs and the established religious institutions and elite. Professor of Talmud, Bar-Ilan University, ISRAEL, [email protected] 1 Introduction This article is an attempt to reconstruct and to describe a unique socio-religious phenomenon which I believe existed towards the end of the second Temple period. -

SYNOPSIS the Mishnah and Tosefta Are Two Related Works of Legal

SYNOPSIS The Mishnah and Tosefta are two related works of legal discourse produced by Jewish sages in Late Roman Palestine. In these works, sages also appear as primary shapers of Jewish law. They are portrayed not only as individuals but also as “the SAGES,” a literary construct that is fleshed out in the context of numerous face-to-face legal disputes with individual sages. Although the historical accuracy of this portrait cannot be verified, it reveals the perceptions or wishes of the Mishnah’s and Tosefta’s redactors about the functioning of authority in the circles. An initial analysis of fourteen parallel Mishnah/Tosefta passages reveals that the authority of the Mishnah’s SAGES is unquestioned while the Tosefta’s SAGES are willing at times to engage in rational argumentation. In one passage, the Tosefta’s SAGES are shown to have ruled hastily and incorrectly on certain legal issues. A broader survey reveals that the Mishnah also contains a modest number of disputes in which the apparently sui generis authority of the SAGES is compromised by their participation in rational argumentation or by literary devices that reveal an occasional weakness of judgment. Since the SAGES are occasionally in error, they are not portrayed in entirely ideal terms. The Tosefta’s literary construct of the SAGES differs in one important respect from the Mishnah’s. In twenty-one passages, the Tosefta describes a later sage reviewing early disputes. Ten of these reviews involve the SAGES. In each of these, the later sage subjects the dispute to further analysis that accords the SAGES’ opinion no more a priori weight than the opinion of individual sages.