Waiting for Yesterday How Syrian Refugees Analyse Their Own Situation and Make Decisions About Their Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dual Naming of Sea Areas in Modern Atlases and Implications for the East Sea/Sea of Japan Case

Dual naming of sea areas in modern atlases and implications for the East Sea/Sea of Japan case Rainer DORMELS* Dual naming is, to varying extents, present in nearly all atlases. The empirical research in this paper deals with the dual naming of sea areas in about 20 atlases from different nations in the years from 2006 to 2017. Objective, quality, and size of the atlases and the country where the atlases originated from play a key role. All these characteristics of the atlases will be taken into account in the paper. In the cases of dual naming of sea areas, we can, in general, differentiate between: cases where both names are exonyms, cases where both names are endonyms, and cases where one name is an endonym, while the other is an exonym. The goal of this paper is to suggest a typology of dual names of sea areas in different atlases. As it turns out, dual names of sea areas in atlases have different functions, and in many atlases, dual naming is not a singular exception. Dual naming may help the users of atlases to orientate themselves better. Additionally, dual naming allows for providing valuable information to the users. Regarding the naming of the sea between Korea and Japan present study has achieved the following results: the East Sea/Sea of Japan is the sea area, which by far showed the most use of dual naming in the atlases examined, in all cases of dual naming two exonyms were used, even in atlases, which allow dual naming just in very few cases, the East Sea/Sea of Japan is presented with dual naming. -

Geographical Names and Sustainable Tourism

No. 59 NOVEMBERNo. 59 NOVEMBER 2020 2020 Geographical Names and Sustainable Tourism Socio- Institutional cultural Sustainable Tourism Economic Environmental Table of Contents The Information Bulletin of the United Nations MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRPERSON ............................................... 3 Group of Experts on Geographical Names (formerly Reconsidérer notre mobilité ......................................................... 3 UNGEGN Newsletter) is issued twice a year by the Secretariat of the Group of Experts. The Secretariat Reconsider our mobility ............................................................... 4 is served by the Statistics Division (UNSD), MESSAGE FROM THE SECRETARIAT ................................................. 5 Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Secretariat of the United Nations. Contributions “Geographical names and sustainable tourism ............................ 5 and reports received from the Experts of the Group, IN MEMORIAM ................................................................................ 7 its Linguistic/Geographical Divisions and its Working Groups are reviewed and edited jointly by the Danutė Janė Mardosienė (1947-2020) ........................................ 7 Secretariat and the UNGEGN Working Group on SPECIAL FEATURE: GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES AND SUSTAINABLE Publicity and Funding. Contributions for the TOURISM ......................................................................................... 9 Information Bulletin can only be considered when they are made -

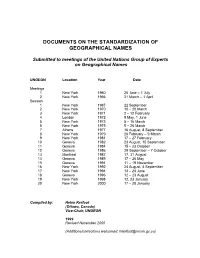

Documents on the Standardization of Geographical Names

DOCUMENTS ON THE STANDARDIZATION OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Submitted to United Nations Conferences on the Standardization of Geographical Names Conference Location Year Date 1 Geneva 1967 4 - 22 September 2 London 1972 10 - 31 May 3 Athens 1977 17 August – 7 September 4 Geneva 1982 24 August – 14 September 5 Montréal 1987 18 - 30 August 6 New York 1992 25 August – 3 September 7 New York 1998 13 – 22 January 8 Berlin 2002 27 August – 5 September 9 New York 2007 21 – 30 August Compiled by: Helen Kerfoot (Ottawa, Canada) Chair, UNGEGN Last revised October 2007 (Additions/corrections welcomed: [email protected]) 1 UN Year Document Symbol Title Country / Division - Working Prepared by copy Co Organization UNGEGN Group - UN nf UNGEGN 1 yes 0 no [FIRST] UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON THE STANDARDIZATION OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES, Geneva, 4 - 22 September, 1967 1st 1967 E/CONF.53/3 United Nations Conference on the Standardization of 1E Co Geographical Names, Vol. 1 Report of the Conference (United 1F nf. Nations Publication E.68.I.9,1968) 1S 1 E/CONF.53/4 United Nations Conference on the Standardization of 1E Geographical Names, Vol. 2 Proceedings of the Conference 1F and technical papers (United Nations Publication E.69.I.8, 1969) 1S 1 The above reports were also published in French and Spanish 1 1967 E/CONF.53/1 Provisional agenda 1E 1F 1 1967 E/CONF.53/2 and Draft report of the Conference 1E Add.1-5 1 1967 E/CONF.53/C.1/1 Draft report of Committee I 1E 1F 1S 1 1967 E/CONF.53/C.2/1 Draft report of Committee II 1E 1F 1S 1 1967 E/CONF.53/C.3/1 Draft -

Familiarity with Slovenian Exonyms in the Professional Community Drago Kladnik, Primož Pipan

ONOMÀSTICA BIBLIOTECA TÈCNICA DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA Familiarity with Slovenian Exonyms in the Professional Community Drago Kladnik, Primož Pipan DOI: 10.2436/15.8040.01.189 Abstract As part of UNGEGN, experts on geographical names are continually striving to limit the use of exonyms, especially in international communication. However, this conflicts with the linguistic heritage of individual peoples as an important element of their cultural heritage. In order to obtain suitable points of departure to prepare the planned standardization of Slovenian exonyms, in the fall of 2010 we used an internet survey to conduct a study on their degree of familiarity among the Slovenian professional community, especially among geographers (teachers, researchers, and others) and linguists. The survey was kept brief for understandable reasons and contained four sets of questions. The first set applied to familiarity with the Slovenian exonyms for seventy European cities, the second to familiarity with the Slovenian exonyms for ten European islands and archipelagos, the third to familiarity with archaic Slovenian exonyms for ten European cities, and the fourth to the most frequently used forms for ten non-European cities with allonyms. We asked the participants to answer the questions off the top of their heads without relying on any kind of literature or browsing the web. We received 167 completed questionnaires and carefully analyzed them. Many of the participants had difficulty recognizing endonyms. A basic finding of the analysis was that the degree of familiarity with individual exonyms varies greatly. ***** 1. Introduction As part of the project “Slovenian Exonyms: Methodology, Standardization, and GIS” at the ZRC SAZU Anton Melik Geographical Institute, we determined the level of familiarity with names for foreign topographic items and features in Slovenian among the professional community. -

UNGEGN Docs Web Mar02

1 UNGEGN Year Wkg Title Country / Division - Working Prepared by Meeting / Paper Organization UNGEGN Group - Session Symbol UNGEGN No. FIRST MEETING OF THE GROUP OF EXPERTS ON GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES, New York, 20 June - 1 July, 1960 Meeting 1 1960 Report of The Group of Experts on Geographical Names to the ECOSOC . E/3441, 7 February 1961 M1 1960 Also "Report of the Group of Experts on Geographical Names", World Cartography , Vol. VII, United Nations Publication 62.I.25 (1962), pp. 7-18. M1 1960 Also in First United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names, Vol. 2 Proceedings of the Conference and technical papers, United Nations Publication E.69.I.8 (1969), E/CONF.53/4, pp. 151-157. M1 1960 French and Spanish versions available in F.69.I.8, 1969 and S.69.I.8, 1969 Apparently no numbered and dated documents were prepared, but documents written previously for other occasions were distributed for discussion. SECOND MEETING OF THE GROUP OF EXPERTS ON GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES, New York, 21 March - 1 April, 1966 Meeting 2 1966 "Preparatory meeting for the United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names: Report of the Group of Experts on Geographical Names", United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names, Vol. 1 Report of the Conference , United Nations Publication 68.I.9 (1968), E/CONF.53/3, Annex III, pp. 20-24. M2 1966 French and Spanish versions of E/CONF.53/3 available FIRST SESSION OF THE GROUP OF EXPERTS ON GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES, New York, 22 September, 1967 Session 1 1967 "Report of the ad hoc Group of Experts on Geographical Names on its First Session", United Nations Conference on the Standardization of Geographical Names, Vol. -

Country Compendium

Country Compendium A companion to the English Style Guide July 2021 Translation © European Union, 2011, 2021. The reproduction and reuse of this document is authorised, provided the sources and authors are acknowledged and the original meaning or message of the texts are not distorted. The right holders and authors shall not be liable for any consequences stemming from the reuse. CONTENTS Introduction ...............................................................................1 Austria ......................................................................................3 Geography ................................................................................................................... 3 Judicial bodies ............................................................................................................ 4 Legal instruments ........................................................................................................ 5 Government bodies and administrative divisions ....................................................... 6 Law gazettes, official gazettes and official journals ................................................... 6 Belgium .....................................................................................9 Geography ................................................................................................................... 9 Judicial bodies .......................................................................................................... 10 Legal instruments ..................................................................................................... -

Dictionary of Slovenian Exonyms Explanatory Notes

GEOGRAFSKI INŠTITUT ANTONA MELIKA ZNANSTVENORAZISKOVALNI CENTER SLOVENSKE AKADEMIJE ZNANOSTI IN UMETNOSTI ANTON MELIK GEOGRAPHICAL INSTITUTE OF ZRC SAZU DICTIONARY OF SLOVENIAN EXONYMS EXPLANATORY NOTES Drago Kladnik Drago Perko AMGI ZRC SAZU Ljubljana 2013 1 Preface The geocoded collection of Slovenia exonyms Zbirka slovenskih eksonimov and the dictionary of Slovenina exonyms Slovar slovenskih eksonimov have been set up as part of the research project Slovenski eksonimi: metodologija, standardizacija, GIS (Slovenian Exonyms: Methodology, Standardization, GIS). They include more than 5,000 of the most frequently used exonyms that were collected from more than 50,000 documented various forms of these types of geographical names. The dictionary contains thirty-four categories and has been designed as a contribution to further standardization of Slovenian exonyms, which can be added to on an ongoing basis and used to find information on Slovenian exonym usage. Currently, their use is not standardized, even though analysis of the collected material showed that the differences are gradually becoming smaller. The standardization of public, professional, and scholarly use will allow completely unambiguous identification of individual features and items named. By determining the etymology of the exonyms included, we have prepared the material for their final standardization, and by systematically documenting them we have ensured that this important aspect of the Slovenian language will not sink into oblivion. The results of this research will not only help preserve linguistic heritage as an important aspect of Slovenian cultural heritage, but also help preserve national identity. Slovenian exonyms also enrich the international treasury of such names and are undoubtedly important part of the world’s linguistic heritage. -

Over the Mountains and Far Away

Over the Mountains and Far Away Studies in Near Eastern history and archaeology presented to Mirjo Salvini on the occasion of his 80th birthday edited by Pavel S. Avetisyan, Roberto Dan and Yervand H. Grekyan Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78491-943-6 ISBN 978-1-78491-944-3 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and authors 2019 Cover image: Mheri duṛ/Meher kapısı. General view of the ‘Gate of Ḫaldi’ (9th century BC) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Oxuniprint, Oxford. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Editorial..........................................................................................................................................................................................iv Foreword .........................................................................................................................................................................................v Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................................................................vi Bīsotūn, ‘Urartians’ and ‘Armenians’ of the Achaemenid Texts, and the Origins of the Exonyms -

UNGEGN Information Bulletin Number 53

No. 53 NOVEMBER 2017 UNGEGN Information Bulletin No. 53 • November 2017 • Page 1 IN THIS ISSUE The Information Bulletin of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (formerly UNGEGN Message from the Chairperson 3 Newsletter) is issued twice a year by the Secretariat of the Group of Experts. The Secretariat is served by the Message from the Secretariat 4 Statistics Division (UNSD), Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Secretariat of the United Nations. Contributions and reports received from the Experts of the Special Feature – 50 Years of UNGEGN Group, its Linguistic/Geographical Divisions and its Working and UNCSGN Groups are reviewed and edited jointly by the Secretariat • UNGEGN: aims and structure 5 and the UNGEGN Working Group on Publicity and Funding. • UNCSGN Presidents 6 Contributions for the Information Bulletin can only be • UNGEGN Sessions Chairs 7 considered when they are made available digitally in • 50 Years of UNCSGN: Honouring some of 8 Microsoft Word or compatible format. They should be sent those who got us here to the following address: 10 • UNGEGN’s publications and communications over the last 50 years Secretariat of the Group of Experts on • The participation of women in UNGEGN 11 Geographical Names (UNGEGN) and UNCSGN activities Room DC2-1678 • Arab Division of Experts on Geographical 14 United Nations Names Division New York, NY 10017 • Achievements of the Hashemite Kingdom 16 USA of Jordan in the field of Geographical • Canada : La gestion des noms de lieux au 18 Tel: (212) 963-5823 -

UNGEGN Docs Web Mar02

DOCUMENTS ON THE STANDARDIZATION OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Submitted to meetings of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names UNGEGN Location Year Date Meetings 1 New York 1960 20 June – 1 July 2 New York 1966 21 March – 1 April Session 1 New York 1967 22 September 2 New York 1970 10 – 20 March 3 New York 1971 2 – 12 February 4 London 1972 9 May, 1 June 5 New York 1973 5 – 16 March 6 New York 1975 5 – 26 March 7 Athens 1977 16 August, 8 September 8 New York 1979 26 February – 9 March 9 New York 1981 17 – 27 February 10 Geneva 1982 23 August, 15 September 11 Geneva 1984 15 – 23 October 12 Geneva 1986 29 September – 7 October 13 Montréal 1987 17, 31 August 14 Geneva 1989 17 – 26 May 15 Geneva 1991 11 – 19 November 16 New York 1992 24 August, 4 September 17 New York 1994 13 – 24 June 18 Geneva 1996 12 – 23 August 19 New York 1998 12, 23 January 20 New York 2000 17 – 28 January Compiled by: Helen Kerfoot (Ottawa, Canada) Vice-Chair, UNGEGN 1999 Revised November 2000 (Additions/corrections welcomed: [email protected]) 1 UNGEGN Year Wkg Title Country / Division - Working Prepared by Meeting / Paper Organization UNGEGN Group - Session Symbol UNGEGN No. FIRST MEETING OF THE GROUP OF EXPERTS ON GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES, New York, 20 June - 1 July, 1960 Meeting 1 1960 Report of The Group of Experts on Geographical Names to the ECOSOC . E/3441, 7 February 1961 M1 1960 Also "Report of the Group of Experts on Geographical Names", World Cartography , Vol. -

Human Rights Handbook for Local and Regional Authorities Vol.1

HUMAN RIGHTS HANDBOOK FOR LOCAL AND REGIONAL AUTHORITIES VOL.1 FIGHTING AGAINST DISCRIMINATION French edition: Manuel sur les droits de l’homme pour les élus locaux et régionaux. Vol.1 Reproduction of the texts in this publication is authorized provided that the full title of the source, namely the Council of Europe, is cited. If they are intended to be used for commercial purposes or translated into one of the non-official languages of the Council of Europe, please contact [email protected]. Printing and graphic design: OPTEMIS Photos: Council of Europe – Shutterstock Edition: February 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS HANDBOOK FOR LOCAL AND REGIONAL AUTHORITIES VOL.1 FIGHTING AGAINST DISCRIMINATION Page 1 Human rights handbook for Local and regional authorities All these contents are available on the following website which is regularly updated with initiatives developed by European local and regional authorities in the field of Human rights. www.coe.int/congress-human-rights For more information: Council of Europe Congress of Local and regional Authorities Monitoring Committee [email protected] Tel: +33 3 88 41 21 10 Page 2 Contents Gudrun MOSLER-TÖRNSTRÖM, President of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe 5 Harald BERGMANN, Congress Spokesperson on Human Rights 7 Foreword 9 WHY PUBLISH A HUMAN RIGHTS HANDBOOK? 13 Why engage with human rights? 14 How can you make use of the handbook on human rights? 15 What are human rights? 16 The role of local and regional authorities: what do human rights provisions -

Places (Search) API Public V1.39.0 Release Notes

Places (Search) API Release Notes Public Version 1.39.0 Places (Search) API Release Notes 2 ► Notices Notice Notices Topics: This section contains document notices. • Legal Notices • Document Information Places (Search) API Release Notes 3 ► Notices Legal Notices © 2016 HERE Global B.V. and its Affiliate(s). All rights reserved. This material, including documentation and any related computer programs, is protected by copyright controlled by HERE. All rights are reserved. Copying, including reproducing, storing, adapting or translating, any or all of this material requires the prior written consent of HERE. This material also contains confidential information, which may not be disclosed to others without the prior written consent of HERE. Trademark Acknowledgements HERE is trademark or registered trademark of HERE Global B.V. Other product and company names mentioned herein may be trademarks or trade names of their respective owners. Disclaimer This content is provided "as-is" and without warranties of any kind, either express or implied, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, satisfactory quality and non-infringement. HERE does not warrant that the content is error free and HERE does not warrant or make any representations regarding the quality, correctness, accuracy, or reliability of the content. You should therefore verify any information contained in the content before acting on it. To the furthest extent permitted by law, under no circumstances, including without limitation the negligence of HERE, shall HERE be liable for any damages, including, without limitation, direct, special, indirect, punitive, consequential, exemplary and/ or incidental damages that result from the use or application of this content, even if HERE or an authorized representative has been advised of the possibility of such damages.