Final Version for Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Power 2.0.Pdf

STATE POWER 2.0 Proof Copy 000 Hussain book.indb 1 9/9/2013 2:02:58 PM This collection is dedicated to the international networks of activists, hactivists, and enthusiasts leading the global movement for Internet freedom. Proof Copy 000 Hussain book.indb 2 9/9/2013 2:02:58 PM State Power 2.0 Authoritarian Entrenchment and Political Engagement Worldwide Edited by MUZAMMIL M. HUSSAIN University of Michigan, USA PHILIP N. HOWARD University of Washington, USA Proof Copy 000 Hussain book.indb 3 9/9/2013 2:02:59 PM © Muzammil M. Hussain and Philip N. Howard 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Muzammil M. Hussain and Philip N. Howard have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editors of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East 110 Cherry Street Union Road Suite 3-1 Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-3818 Surrey, GU9 7PT USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Howard, Philip N. State Power 2.0 : Authoritarian Entrenchment and Political Engagement Worldwide / by Philip N. Howard and Muzammil M. Hussain. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4094-5469-4 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4094-5470-0 (ebook) -- ISBN 978- 1-4724-0328-5 (epub) 1. -

Text Práce (386.9Kb)

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE 2012 Jakub Dohnal Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Ústav informačních studií a knihovnictví Studijní program: Informační studia a knihovnictví Studijní obor: Informační studia a knihovnictví Bakalářská práce Jakub Dohnal Fenomén pirátského hnutí u nás i ve světě The Pirate movement phenomenon in the world and the Czech Republic Praha, 2012 Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Vít Šisler, PhD. Děkuji svému vedoucímu Mgr. Vítu Šislerovi, PhD. za trpělivost, ochotu a podnětné připomínky při tvorbě této bakalářské práce. Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně, že jsem řádně citoval všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Praze dne 14. července 2012 …........................................ podpis studenta Abstrakt Předložená bakalářská práce se zabývá historií, vznikem, principy a konkrétními aktivitami pirátských stran ve světě a v České republice. V úvodu autor představuje historii a kontext pirátského hnutí, konkrétně na příkladech skupin kolem hackingu, svobodného softwaru či open access. Více rozebírá i myšlenky zastávané zakladatelem Free software foundation Richardem Stallmanem a známým americkým právníkem Lawrence Lessigem, ze kterých vychází základní pirátské principy, jako je svoboda informací, ochrana soukromí, nebo reforma autorského práva. Po definici vybraných základních informačních politik je v práci popsán vznik a činnosti samotných pirátských stran v Evropě. Důraz je kladen na první Piráty ve Švédsku, na úspěšnou německou Pirátskou stranu, na problémy internetové politiky ve Francii (zejména zákony DADVSI a HADOPI) a na situaci v Evropské unii (s důrazem na mezinárodní smlouvu ACTA). Závěrem je představena historie a informační politika České pirátské strany, jež autor porovnává s informační politikou České republiky ve světle základních principů pirátského hnutí. -

Bradley Manning Nobel Peace Prize Nomination 2013

Bradley Manning Nobel Peace Prize Nomination 2013 By Global Research News Theme: Law and Justice Global Research, March 04, 2013 Birgitta Jónsdóttir official blog and news- beacon-ireland.info by Birgitta Jónsdóttir February 1st 2013 the entire parliamentary group of The Movement in the Icelandic Parliament, the Pirates of the EU; representatives from the Swedish Pirate Party, the former Secretary of State in Tunisia for Sport & Youth nominated Private Bradley Manning for the Nobel Peace Prize. Following is the reasoning we sent to the committee explaining why we felt compelled to nominate Private Bradley Manning for this important recognition of an individual effort to have an impact for peace in our world. The lengthy personal statement to the pre-trial hearing February 28th by Bradley Manning in his own words validate that his motives were for the greater good of humankind. Read his full statement Our letter to the Nobel Peace Prize Committee Reykjavík, Iceland 1st of February 2013 Dear Norwegian Nobel Committee, We have the great honour of nominating Private First Class Bradley Manning for the 2013 Nobel Peace Prize. Manning is a soldier in the United States army who stands accused of releasing hundreds of thousands of documents to the whistleblower website WikiLeaks. The leaked documents pointed to a long history of corruption, war crimes, and a lack of respect for the sovereignty of other democratic nations by the United States government in international dealings. These revelations have fueled democratic uprisings around the world, including a democratic revolution in Tunisia. According to journalists, his alleged actions helped motivate the democratic Arab Spring movements, shed light on secret corporate influence on the foreign and domestic policies of European nations, and most recently contributed to the Obama Administration agreeing to withdraw all U.S.troops from the occupation in Iraq. -

Winds of Democratic Change in the Mediterranean? Processes, Actors and Possible Outcomes

Stefania Panebianco and Rosa Rossi Winds of Democratic Change in the Mediterranean? Processes, Actors and Possible Outcomes Rubbettino !is project has been funded with support from the European Commission. !is publication re"ects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Cover Photograph by Salvatore Tomarchio/StudioTribbù, Acireale (CT) © 2012 - Rubbettino Editore 88049 Soveria Mannelli Viale Rosario Rubbettino, 10 tel (0968) 6664201 www.rubbettino.it Contents Contributors ! Acknowledgements "# Foreword by Amb. Klaus Ebermann "$ Introduction: Winds of Democratic Change in MENA Countries? Rosa Rossi "! %&'( " Democratization Processes: !eoretical and Empirical Issues ". !e Problem of Democracy in the MENA Region Davide Grassi #$ ). Of Middle Classes, Economic Reforms and Popular Revolts: Why Democratization !eory Failed, Again Roberto Roccu *" #. Equal Freedom and Equality of Opportunity Ian Carter +# ,. Tolerance without Values Fabrizio Sciacca !- $. EU Bottom-up Strategies of Democracy Promotion in Middle East and North Africa Rosa Rossi ".- *. Religion and Democratization: an Assessment of the Turkish Model Luca Ozzano "#" 6 %&'( ) Actors of Democracy Promotion: the Intertwining of Domestic and International Dimensions -. Democratic Turmoil in the MENA Area: Challenges for the EU as an External Actor of Democracy Promotion Stefania Panebianco "$" +. !e Role of Parliamentary Bodies, Sub-State Regions, and Cities in the Democratization of the Southern Mediterranean Rim Stelios Stavridis, Roderick Pace and Paqui Santonja "-" !. !e United States and Democratization in the Middle East: From the Clinton Administration to the Arab Spring Maria Do Céu Pinto )." ".. From Turmoil to Dissonant Voices: the Web in the Tunisian !awra Daniela Melfa and Guido Nicolosi )"$ "". -

Piracy and the Politics of Social Media

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Piracy and the Politics of Social Media Martin Fredriksson Almqvist Department for Culture Studies, Linköping University, 601 74 Norrköping, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-11-363-492 Academic Editor: Terri Towner Received: 13 June 2016; Accepted: 20 July 2016; Published: 5 August 2016 Abstract: Since the 1990s, the understanding of how and where politics are made has changed radically. Scholars such as Ulrich Beck and Maria Bakardjieva have discussed how political agency is enacted outside of conventional party organizations, and political struggles increasingly focus on single issues. Over the past two decades, this transformation of politics has become common knowledge, not only in academic research but also in the general political discourse. Recently, the proliferation of digital activism and the political use of social media are often understood to enforce these tendencies. This article analyzes the Pirate Party in relation to these theories, relying on almost 30 interviews with active Pirate Party members from different parts of the world. The Pirate Party was initially formed in 2006, focusing on copyright, piracy, and digital privacy. Over the years, it has developed into a more general democracy movement, with an interest in a wider range of issues. This article analyzes how the party’s initial focus on information politics and social media connects to a wider range of political issues and to other social movements, such as Arab Spring protests and Occupy Wall Street. Finally, it discusses how this challenges the understanding of information politics as a single issue agenda. Keywords: piracy; Pirate Party; political mobilization; political parties; information politics; social media; activism 1. -

The Pirate Party and the Politics of Communication

International Journal of Communication 9(2015), 909–924 1932–8036/20150005 The Pirate Party and the Politics of Communication MARTIN FREDRIKSSON Linköping University, Sweden1 This article draws on a series of interviews with members of the Pirate Party, a political party focusing on copyright and information politics, in different countries. It discusses the interviewees’ visions of democracy and technology and explains that copyright is seen as not only an obstacle to the free consumption of music and movies but a threat to the freedom of speech, the right to privacy, and a thriving public sphere. The first part of this article briefly sketches how the Pirate Party’s commitment to the democratic potential of new communication technologies can be interpreted as a defense of a digitally expanded lifeworld against the attempts at colonization by market forces and state bureaucracies. The second part problematizes this assumption by discussing the interactions between the Pirate movement and the tech industry in relation to recent theories on the connection between political agency and social media. Keywords: piracy, Pirate Party, copyright, social movement Introduction In the wake of the Arab Spring, much hope was invested in social media as a means to mobilize popular resistance. New technologies for decentralized popular communication, such as Twitter and Facebook, were celebrated as tools in the struggle against authoritarian regimes. Later in 2011, the U.S. Congress experienced the impact of digital mobilization when the proposed bills of the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA) were withdrawn due to massive protests. Digital rights activists were alarmed by what was perceived as limitations of free speech, and tech Martin Fredriksson: [email protected] Date submitted: 2015–02–03 1 I would like to thank Professor William Uricchio for inviting me to the Comparative Media Studies Program at MIT to conduct a pilot study in 2011 and 2012. -

WP109 Bouhdiba

African Studies Centre Leiden, The Netherlands Will Sub-Saharan Africa follow North Africa? Backgrounds and preconditions of popular revolt in the light of the ‘Arab spring’ Sofiane Bouhdiba ASC Working Paper 109/2013 University of Tunis 1 African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Telephone +31 71 5273372 Email [email protected] Website www.ascleiden.nl [email protected] © Sofiane Bouhdiba, 2013 2 INTRODUCTION 1 The year 2011 has undeniably been a special one for the African continent. On 14 January 2011 massive street protests in Tunisia ousted President Z. Ben Ali, a long-time North African leader, 2 leading to what has been called the ‘Jasmine Revolution’. 3 Two weeks later, Egypt successfully engaged in its own revolutionary movement. The totalitarian Libyan regime would end one year later with the brutal death of Mouammar al- Gaddafi on 20 October 2011. In the space of one year and a half, three serving presidents were forced out of office by their own people. In a contagious movement, this seemingly unstoppable wave of revolution inspired popular rebellion movements in other Arab countries. In some of them, such as Algeria, Morocco, or Bahrain, the popular contestation seems to have been abandoned by late 2012, while other countries, such as Yemen and especially Syria, are still today immersed in civil war. In 1992 Samuel Huntington referred to the political liberalization movements in Central Europe as the ‘ third democratic wave in history’.4 In the same spirit, and following the chronology of events, we could consider the Arab Spring as the ‘ fourth wave’ . -

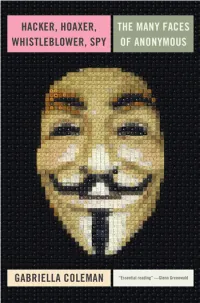

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future. -

The Arab Spring: Will It Lead to Democratic Transitions?

The Arab Spring: Will It Lead to Democratic Transitions? The Arab Spring Will It Lead to Democratic Transitions? Edited by Clement Henry and Jang Ji-Hyang The Asan Institute for Policy Studies 1 The Arab Spring: Will It Lead to Democratic Transitions? CONTENTS Introduction Clement Henry, Jang Ji-Hyang, and Robert P. Parks Part 1) Domestic Political Transition and Regional Spillover 1. ―Early Adopters‖ and ―Neighborhood Effects‖ Lisa Anderson, The American University in Cairo (short paper) 2. A Modest Transformation: Political Change in the Arab World after the ―Arab Spring‖ Eva Bellin, Brandeis University Part 2) Economic Correlates of Political Mobilization 3. Political Economies of Transition Clement Henry, The University of Texas at Austin and The American University in Cairo Part 3) Social Networks and Civil Society 4. New Actors of the Revolution and the Political Transition in Tunisia Mohamed Kerrou, University of Tunis, El Manar 5. Algeria and the Arab Uprisings Robert P. Parks, Centre d'Etudes Maghrébines en Algérie 6. The Plurality of Politics in Post-Revolutionary Iran Arang Keshavarzian, New York University (short paper) Part 4) Varieties of Political Islam 7. The Evolution of Islamist Movements Fawaz Gerges, London School of Economics and Political Science (short paper) 8. Islamic Capital and Democratic Deepening Jang Ji-Hyang, The Asan Institute for Policy Studies 9. Is the Turkish Model relevant for the Middle East? Kemal Kirişci, Boğaziçi University Part 5) Protracted Violence in Syria and Libya 2 The Arab Spring: Will It Lead to Democratic Transitions? 10. Libya after the Civil War: The Legacy of the Past and Economic Reconstruction Diederik Vandewalle, Dartmouth College 11. -

11 03 31 Speech

Cyber-Activism and Human Rights Agnes Callamard, ARTICLE 19 Executive Director A presentation for the Launch of the FCO 2010 report on human rights and democracy, March 31st, 2011 Many thanks to the Foreign Secretary William Hague for giving ARTICLE 19 the opportunity to join in the launch of the FCO annual report on human rights and democracy, which is a valuable resource on the UK’s perspective and record on human rights. This report is a vital tool as the UK public and civil society broadly assesses a government’s performance and seeks its accountability for this. My contribution today will be on a standout human rights issue, one that is taking on even more strategic significance given its contemporary reach, relevance and impact: and that is freedom of expression and particularly on-line expression. ARTICLE 19 is a freedom of expression organisation, established 23 years ago, headquartered in London and with 5 regional offices and some 50 close partners around the world. We take our mandate from article 19 of the UDHR which states that “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; … to hold opinions without interference … to seek, receive and impart information and ideas regardless of frontiers and any media - electronic, organised, social or otherwise. Today, more than ever before, it is access to the means of distribution of expression that is playing a critical role in struggles for freedom and for human rights. Access to electronic media, to the Internet, and the cyber activism that this enables, have emerged as essential to movements for greater freedom and, perhaps more surprisingly, as essential even to revolution. -

Strategic Foresight Retreat

2015 Strategic foresight retreat 10 to 14 August 2015 Hartwell House 2015 Welcome to SOIF 2015! It is with enormous pleasure that we welcome you to SOIF’s fourth annual retreat on Strategic foresight. In the summer of 2012 we launched the School of International Futures with our first retreat at Wilton Park. We were immediately encouraged by the number of people ready to sign up to a week-long retreat on strategic foresight, in the middle of their summer holidays. Particularly gratifying was the range of nationalities and backgrounds of those who joined us, and the attitude of those who came: wanting to learn and discuss foresight not simply as a theory or discipline, but as a way of understanding and changing the future. The attitude and expectations of our participants have shaped SOIF into an organisation dedicated to teaching and promoting foresight as a practical discipline for policy and planning but also one that transforms the world we live in, and helps us make better decisions today, for a better future. We try to do three things: make you better users and commissioners of foresight; send you back to your job after your time with us ready to build future-ready organisations; and encourage you to learn from each other and support each other as a foresight community. The process, methodology and techniques we’ll introduce at SOIF2015 – with the help of our visiting faculty – are ones we have found achieve results in a range of different organisations. But strategic foresight is an art as well as a science; we will ask you to draw on both as you grapple during guided sessions with the Live challenge brought by our policy client, the European External Action Service (EEAS). -

Politica E Istituzioni

POLITICA E ISTITUZIONI DELLE ORGANIZZAZIONI INTERNAZIONALI Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 Prof. Fabio Marazzi 1 INDICE Introduzione………………………………………………………………… pag. 4 1. Cenni storici………………………………………………………………… pag. 11 2. Carattere e struttura delle organizzazioni internazionali…………………... pag. 16 3. Disciplina e classificazione…………………………………………………. pag. 19 4. Caratteristiche delle organizzazioni non governative internazionali (ONG).. pag. 28 5. Ruolo, funzioni, efficacia delle organizzazioni internazionali……………. pag. 35 6 La globalizzazione alla luce delle forze globali…………………………… pag. 40 7. Multilateralismo e società internazionale………………………………….. pag. 43 7.1 ONG e sindacati……………………………………………………... pag. 47 7.2 ONG e Unione Europea……………………………………………… pag. 53 7.3 ONG e globalizzazione………………………………………………. pag. 64 8. Cooperazione internazionale allo sviluppo; cooperazione decentrata…… pag. 71 9. Il principio di condizionalità nel quadro della cooperazione allo sviluppo.. pag. 118 10. Organizzazioni intergovernative…………………………………………… pag. 127 10.1 Società Delle Nazioni ed ONU…………………………………….. pag. 127 10.1.1 La carta delle Nazioni Unite…………………………………. pag. 132 10.1.2 La “Responsibility to protect”……………………………… pag. 137 10.1.3 Interventi umanitari………………………………………….. pag. 140 10.1.4 Il dibattito sulle riforme delle Nazioni Unite……………….. pag. 156 2 10.2 WTO, FMI e BM: globalizzazione e scenari di politica economica.. pag. 190 10.3 Una riflessione: Nota su finanza e sviluppo del Pontificio consiglio della giustizia e della pace……………………………………………….. pag. 212 10.4 Nuovi modelli di sostegno finanziario basati su modelli sociali….. pag. 229 10.4 Unione Europea…………………………………………………..... pag. 240 11. Prospettive………………………………………………………………….. pag. 251 12. Organizzazioni non governative……………………………………………. pag. 254 12.1 Croce Rossa e mezzaluna Rossa…………………………………… pag. 254 12.2 Altre ONG………………………………………………………….. pag. 260 12.2.1 Greenpeace…………………………………………………… pag. 260 12.2.2 Unesco………………………………………………………... pag. 262 12.2.3 W.W.F………………………………………………………..