WP109 Bouhdiba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Media and the Arab Spring Philip N. Howard & Muzammil M

Digital Media and the Arab Spring Philip N. Howard & Muzammil M. Hussain Philip N. Howard is associate professor at the University of Washington. He is the author of The Digital Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Information Technology and Political Islam (2010). Muzammil M. Hussain is a doctoral student in communication at the University of Washington. As has often been noted in these pages, one world region has been practically untouched by the third wave of democratization: North Africa and the Middle East. The Arab world has lacked not only democracy, but even large popular movements pressing for it. In December 2010 and the first months of 2011, however, this situation changed with stunning speed. Massive and sustained public demonstrations demanding political reform cascaded from Tunis to Cairo, Sana’a, Amman, and Manama. This inspired people in Casablanca, Damascus, Tripoli, and dozens of other cities to take to the streets to call for change. By May, major political casualties littered the ground: Tunisia’s Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali and Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, two of the region’s oldest dictators, were gone; the Libyan regime of Muammar Qadhafi was battling an armed rebellion that had taken over half the country and attracted NATO help; and several monarchs had sacked their cabinets and committed to constitutional reforms. Governments around the region had sued for peace by promising their citizens hundreds of billions of dollars in new spending of various kinds. Morocco and Saudi Arabia appeared to be fending off serious domestic uprisings, but as of this writing in May 2011, the outcomes for regimes in Bahrain, Jordan, Syria, and Yemen remain far from certain. -

ECPR General Conference

13th General Conference University of Wrocław, 4 – 7 September 2019 Contents Welcome from the local organisers ........................................................................................ 2 Mayor’s welcome ..................................................................................................................... 3 Welcome from the Academic Convenors ............................................................................ 4 The European Consortium for Political Research ................................................................... 5 ECPR governance ..................................................................................................................... 6 Executive Committee ................................................................................................................ 7 ECPR Council .............................................................................................................................. 7 University of Wrocław ............................................................................................................... 8 Out and about in the city ......................................................................................................... 9 European Political Science Prize ............................................................................................ 10 Hedley Bull Prize in International Relations ............................................................................ 10 Plenary Lecture ....................................................................................................................... -

Transnational Pirates

Attachment A Tab. A1 Survey Overview Countries Pirate Party Name Status Contacted Response Belgium Pirate Party Belgium Officially registered 1 1 Piratska Partia / Bulgaria Officially registered 1 Пиратска Партия Denmark Piratpartiet Officially registered 1 1 Germany Piratenpartei Deutschland Officially registered 1 1 Finland Piraattipuolue Officially registered 1 1 France Parti Pirate Officially registered 1 1 United Kingdom Pirate Party UK Officially registered 1 1 Italy Partito Pirata Italiano Officially registered 1 Pirate Party of Canada / Canada Officially registered 1 1 Parti Pirate du Canada Catalonia/Spain Pirates de Catalunya Officially registered 1 1 Luxembourg Piratepartei Lëtzebuerg Officially registered 1 1 The Netherlands Piratenpartij Nederland Officially registered 1 Austria Piratenpartei Österreichs Officially registered 1 1 Sweden Piratpartiet Officially registered 1 1 Switzerland Piratenpartei Schweiz Officially registered 1 1 Spain Partido Pirata Officially registered 1 Czech Republic Česká pirátská strana Officially registered 1 1 United States United States Pirate Party Officially registered 1 1 Argentina Partido Pirata Argentino Active group 1 1 Australia Pirate Party Australia Active group 1 Piratska Partija Bosna i Active group Bosnia and Hercegovina / 1 Herzegovina Пиратска Партија Босна и Херцеговина Brazil Partido Pirata do Brasil Active group 1 Chile Partido Pirata de Chile Active group 1 1 El Salvador Partido Pirata de El Salvador Active group 1 Greece Κό !"# Active group 1 Guatemala Partido Pirata Guatemala -

State Power 2.0.Pdf

STATE POWER 2.0 Proof Copy 000 Hussain book.indb 1 9/9/2013 2:02:58 PM This collection is dedicated to the international networks of activists, hactivists, and enthusiasts leading the global movement for Internet freedom. Proof Copy 000 Hussain book.indb 2 9/9/2013 2:02:58 PM State Power 2.0 Authoritarian Entrenchment and Political Engagement Worldwide Edited by MUZAMMIL M. HUSSAIN University of Michigan, USA PHILIP N. HOWARD University of Washington, USA Proof Copy 000 Hussain book.indb 3 9/9/2013 2:02:59 PM © Muzammil M. Hussain and Philip N. Howard 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Muzammil M. Hussain and Philip N. Howard have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editors of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East 110 Cherry Street Union Road Suite 3-1 Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-3818 Surrey, GU9 7PT USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Howard, Philip N. State Power 2.0 : Authoritarian Entrenchment and Political Engagement Worldwide / by Philip N. Howard and Muzammil M. Hussain. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4094-5469-4 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4094-5470-0 (ebook) -- ISBN 978- 1-4724-0328-5 (epub) 1. -

Text Práce (386.9Kb)

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE 2012 Jakub Dohnal Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická fakulta Ústav informačních studií a knihovnictví Studijní program: Informační studia a knihovnictví Studijní obor: Informační studia a knihovnictví Bakalářská práce Jakub Dohnal Fenomén pirátského hnutí u nás i ve světě The Pirate movement phenomenon in the world and the Czech Republic Praha, 2012 Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Vít Šisler, PhD. Děkuji svému vedoucímu Mgr. Vítu Šislerovi, PhD. za trpělivost, ochotu a podnětné připomínky při tvorbě této bakalářské práce. Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně, že jsem řádně citoval všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Praze dne 14. července 2012 …........................................ podpis studenta Abstrakt Předložená bakalářská práce se zabývá historií, vznikem, principy a konkrétními aktivitami pirátských stran ve světě a v České republice. V úvodu autor představuje historii a kontext pirátského hnutí, konkrétně na příkladech skupin kolem hackingu, svobodného softwaru či open access. Více rozebírá i myšlenky zastávané zakladatelem Free software foundation Richardem Stallmanem a známým americkým právníkem Lawrence Lessigem, ze kterých vychází základní pirátské principy, jako je svoboda informací, ochrana soukromí, nebo reforma autorského práva. Po definici vybraných základních informačních politik je v práci popsán vznik a činnosti samotných pirátských stran v Evropě. Důraz je kladen na první Piráty ve Švédsku, na úspěšnou německou Pirátskou stranu, na problémy internetové politiky ve Francii (zejména zákony DADVSI a HADOPI) a na situaci v Evropské unii (s důrazem na mezinárodní smlouvu ACTA). Závěrem je představena historie a informační politika České pirátské strany, jež autor porovnává s informační politikou České republiky ve světle základních principů pirátského hnutí. -

Digital Democracy: the Tools Transforming Political Engagement

Digital Democracy The tools transforming political engagement Julie Simon, Theo Bass, Victoria Boelman and Geoff Mulgan February 2017 nesta.org.uk Acknowledgements ThisThis work work would containsnot have been statistical possible without data fromthe support ONS of which many people is Crown and Copyright. The organisations.use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement Weof are the extremely ONS gratefulin relation for the to support the interpretation of the MacArthur orFoundation analysis Research of the Networkstatistical on data.Opening This Governance work uses who fundedresearch this studydatasets and provided which helpfulmay notinsight exactly and expertise reproduce throughoutNational the Statisticsprocess. aggregates. We would also like to thank all those who gave up their time to speak with us about the digital democracy initiatives with which they are involved: Miguel Arana Catania, Davide Barillari, Matthew Bartlett, Yago Bermejo, Róbert Bjarnason, Ari Brodach, Diego Cunha, Kevin Davies, Thibaut Dernoncourt, Christiano Ferri Soares de Faria, Ben Fowkes, Roslyn Fuller, Raimond Garcia, Gunnar Grímsson, Hille Hinsberg, Chia-Liang Kao, Joseph Kim, Joël Labbé, Smári McCarthy, Colin Megill, Felipe Munoz, Razak Musah, Nicolas Patte, Teele Pehk, Joonas Pekkanen, Jinsun Lee, Clémence Pène, Maarja-Leena Saar, Tom Shane, ArnaldurAcknowledgements Sigurðarson, Audrey Tang, and Sjöfn Vilhelmsdóttir. Finally, the insightful comments of our peer reviewers on the draft of this report were Johanna Bolhoven, Gail Caig, Caroline Norbury and Dawn Payne at Creative England have invaluable in helping shape the final outcome: Stefaan Verhulst, Cristiano Ferri Soares de contributed valuable input and feedback to the project from its beginning. Federico Cilauro and Faria, Eddie Copeland. -

Bradley Manning Nobel Peace Prize Nomination 2013

Bradley Manning Nobel Peace Prize Nomination 2013 By Global Research News Theme: Law and Justice Global Research, March 04, 2013 Birgitta Jónsdóttir official blog and news- beacon-ireland.info by Birgitta Jónsdóttir February 1st 2013 the entire parliamentary group of The Movement in the Icelandic Parliament, the Pirates of the EU; representatives from the Swedish Pirate Party, the former Secretary of State in Tunisia for Sport & Youth nominated Private Bradley Manning for the Nobel Peace Prize. Following is the reasoning we sent to the committee explaining why we felt compelled to nominate Private Bradley Manning for this important recognition of an individual effort to have an impact for peace in our world. The lengthy personal statement to the pre-trial hearing February 28th by Bradley Manning in his own words validate that his motives were for the greater good of humankind. Read his full statement Our letter to the Nobel Peace Prize Committee Reykjavík, Iceland 1st of February 2013 Dear Norwegian Nobel Committee, We have the great honour of nominating Private First Class Bradley Manning for the 2013 Nobel Peace Prize. Manning is a soldier in the United States army who stands accused of releasing hundreds of thousands of documents to the whistleblower website WikiLeaks. The leaked documents pointed to a long history of corruption, war crimes, and a lack of respect for the sovereignty of other democratic nations by the United States government in international dealings. These revelations have fueled democratic uprisings around the world, including a democratic revolution in Tunisia. According to journalists, his alleged actions helped motivate the democratic Arab Spring movements, shed light on secret corporate influence on the foreign and domestic policies of European nations, and most recently contributed to the Obama Administration agreeing to withdraw all U.S.troops from the occupation in Iraq. -

Winds of Democratic Change in the Mediterranean? Processes, Actors and Possible Outcomes

Stefania Panebianco and Rosa Rossi Winds of Democratic Change in the Mediterranean? Processes, Actors and Possible Outcomes Rubbettino !is project has been funded with support from the European Commission. !is publication re"ects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Cover Photograph by Salvatore Tomarchio/StudioTribbù, Acireale (CT) © 2012 - Rubbettino Editore 88049 Soveria Mannelli Viale Rosario Rubbettino, 10 tel (0968) 6664201 www.rubbettino.it Contents Contributors ! Acknowledgements "# Foreword by Amb. Klaus Ebermann "$ Introduction: Winds of Democratic Change in MENA Countries? Rosa Rossi "! %&'( " Democratization Processes: !eoretical and Empirical Issues ". !e Problem of Democracy in the MENA Region Davide Grassi #$ ). Of Middle Classes, Economic Reforms and Popular Revolts: Why Democratization !eory Failed, Again Roberto Roccu *" #. Equal Freedom and Equality of Opportunity Ian Carter +# ,. Tolerance without Values Fabrizio Sciacca !- $. EU Bottom-up Strategies of Democracy Promotion in Middle East and North Africa Rosa Rossi ".- *. Religion and Democratization: an Assessment of the Turkish Model Luca Ozzano "#" 6 %&'( ) Actors of Democracy Promotion: the Intertwining of Domestic and International Dimensions -. Democratic Turmoil in the MENA Area: Challenges for the EU as an External Actor of Democracy Promotion Stefania Panebianco "$" +. !e Role of Parliamentary Bodies, Sub-State Regions, and Cities in the Democratization of the Southern Mediterranean Rim Stelios Stavridis, Roderick Pace and Paqui Santonja "-" !. !e United States and Democratization in the Middle East: From the Clinton Administration to the Arab Spring Maria Do Céu Pinto )." ".. From Turmoil to Dissonant Voices: the Web in the Tunisian !awra Daniela Melfa and Guido Nicolosi )"$ "". -

Piracy and the Politics of Social Media

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Piracy and the Politics of Social Media Martin Fredriksson Almqvist Department for Culture Studies, Linköping University, 601 74 Norrköping, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-11-363-492 Academic Editor: Terri Towner Received: 13 June 2016; Accepted: 20 July 2016; Published: 5 August 2016 Abstract: Since the 1990s, the understanding of how and where politics are made has changed radically. Scholars such as Ulrich Beck and Maria Bakardjieva have discussed how political agency is enacted outside of conventional party organizations, and political struggles increasingly focus on single issues. Over the past two decades, this transformation of politics has become common knowledge, not only in academic research but also in the general political discourse. Recently, the proliferation of digital activism and the political use of social media are often understood to enforce these tendencies. This article analyzes the Pirate Party in relation to these theories, relying on almost 30 interviews with active Pirate Party members from different parts of the world. The Pirate Party was initially formed in 2006, focusing on copyright, piracy, and digital privacy. Over the years, it has developed into a more general democracy movement, with an interest in a wider range of issues. This article analyzes how the party’s initial focus on information politics and social media connects to a wider range of political issues and to other social movements, such as Arab Spring protests and Occupy Wall Street. Finally, it discusses how this challenges the understanding of information politics as a single issue agenda. Keywords: piracy; Pirate Party; political mobilization; political parties; information politics; social media; activism 1. -

Success and Personality

The electoral success of angels and demons. Big Five, Dark Triad, and performance at the ballot box Article forthcoming in the Journal of Social and Political Psychology Alessandro Nai, University of Amsterdam ([email protected]) Appendix Appendix A – Elections and candidates Appendix B – Robustness checks and additional analyses Appendix C – Measures of personality reputation Appendix D – Experts 1 Appendix A Elections and candidates Table A1. Elections Country Election Date Albania Parliamentary election 25-Jun-17 Algeria Election of the National People's Assembly 4-May-17 Argentina Legislative election 22-Oct-17 Armenia Parliamentary election 2-Apr-17 Australia Federal election 2-Jul-16 Austria a Presidential election 4-Dec-16 Austria Legislative election 15-Oct-17 Bulgaria Presidential election 6-Nov-16 Bulgaria Legislative election 26-Mar-17 Chile Presidential election 19-Nov-17 Costa Rica Presidential election 4-Feb-18 Croatia Election of the Assembly 11-Sep-16 Cyprus Presidential election 28-Jan-18 Czech Republic Legislative election 20-Oct-17 Czech Republic Presidential election 12-Jan-18 Ecuador Presidential election 19-Feb-17 Finland Presidential election 28-Jan-18 France Presidential election 23-Apr-17 France Election of the National Assembly 11-Jun-17 Georgia Parliamentary election 8-Oct-16 Germany Federal elections 24-Sep-17 Ghana Presidential election 7-Dec-16 Iceland Presidential election 25-Jun-16 Iceland Election for the Althing 29-Oct-16 Iceland Election for the Althing 28-Oct-17 Iran Presidential election 19-May-17 Italy -

The Pirate Party and the Politics of Communication

International Journal of Communication 9(2015), 909–924 1932–8036/20150005 The Pirate Party and the Politics of Communication MARTIN FREDRIKSSON Linköping University, Sweden1 This article draws on a series of interviews with members of the Pirate Party, a political party focusing on copyright and information politics, in different countries. It discusses the interviewees’ visions of democracy and technology and explains that copyright is seen as not only an obstacle to the free consumption of music and movies but a threat to the freedom of speech, the right to privacy, and a thriving public sphere. The first part of this article briefly sketches how the Pirate Party’s commitment to the democratic potential of new communication technologies can be interpreted as a defense of a digitally expanded lifeworld against the attempts at colonization by market forces and state bureaucracies. The second part problematizes this assumption by discussing the interactions between the Pirate movement and the tech industry in relation to recent theories on the connection between political agency and social media. Keywords: piracy, Pirate Party, copyright, social movement Introduction In the wake of the Arab Spring, much hope was invested in social media as a means to mobilize popular resistance. New technologies for decentralized popular communication, such as Twitter and Facebook, were celebrated as tools in the struggle against authoritarian regimes. Later in 2011, the U.S. Congress experienced the impact of digital mobilization when the proposed bills of the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA) were withdrawn due to massive protests. Digital rights activists were alarmed by what was perceived as limitations of free speech, and tech Martin Fredriksson: [email protected] Date submitted: 2015–02–03 1 I would like to thank Professor William Uricchio for inviting me to the Comparative Media Studies Program at MIT to conduct a pilot study in 2011 and 2012. -

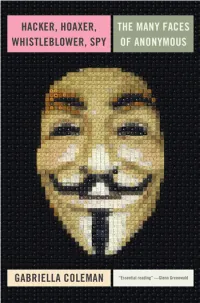

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: the Story of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York First published by Verso 2014 © Gabriella Coleman 2014 The partial or total reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-583-9 eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-584-6 (US) eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-689-8 (UK) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the library of congress Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in the US by Maple Press Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY I dedicate this book to the legions behind Anonymous— those who have donned the mask in the past, those who still dare to take a stand today, and those who will surely rise again in the future.