James GRIFFITH the Leviathan Becoming A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Programme for the Xvith International Congress of Celtic Studies

Logo a chynllun y clawr Cynlluniwyd logo’r XVIeg Gyngres gan Tom Pollock, ac mae’n seiliedig ar Frigwrn Capel Garmon (tua 50CC-OC50) a ddarganfuwyd ym 1852 ger fferm Carreg Goedog, Capel Garmon, ger Llanrwst, Conwy. Ceir rhagor o wybodaeth ar wefan Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru: https://amgueddfa.cymru/oes_haearn_athrawon/gwrthrychau/brigwrn_capel_garmon/?_ga=2.228244894.201309 1070.1562827471-35887991.1562827471 Cynlluniwyd y clawr gan Meilyr Lynch ar sail delweddau o Lawysgrif Bangor 1 (Archifau a Chasgliadau Arbennig Prifysgol Bangor) a luniwyd yn y cyfnod 1425−75. Mae’r testun yn nelwedd y clawr blaen yn cynnwys rhan agoriadol Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, cyfieithiad Cymraeg o De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum, gan Hu Sant (Hugo o St. Victor). Rhan o ramadeg barddol a geir ar y clawr ôl. Logo and cover design The XVIth Congress logo was designed by Tom Pollock and is based on the Capel Garmon Firedog (c. 50BC-AD50) which was discovered in 1852 near Carreg Goedog farm, Capel Garmon, near Llanrwst, Conwy. Further information will be found on the St Fagans National Museum of History wesite: https://museum.wales/iron_age_teachers/artefacts/capel_garmon_firedog/?_ga=2.228244894.2013091070.156282 7471-35887991.1562827471 The cover design, by Meilyr Lynch, is based on images from Bangor 1 Manuscript (Bangor University Archives and Special Collections) which was copied 1425−75. The text on the front cover is the opening part of Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, a Welsh translation of De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum (Hugo of St. Victor). The back-cover text comes from the Bangor 1 bardic grammar. -

The Threefold Movement of St. Adalbertâ•Žs Head

Beihefte zur Mediaevistik: Band 29 2016 Andrea Grafetstätter / Sieglinde Hartmann / James Ogier (eds.) 2016 , Islands · and Cities in Medieval Myth, Literature, and History. Papers Delivered at the International Medieval Congress, Univer-sity of Leeds, in 2005, 2006, and 2007 (2011) Internationale Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Mittelalterforschung Olaf Wagener (Hrsg.), „vmbringt mit starcken turnen, murn“. Ortsbefesti- Band 29 gungen im Mittelalter (2010) Hiram Kümper (Hrsg.), eLearning & Mediävistik. Mittelalter lehren und lernen im neumedialen Zeitalter (2011) Olaf Wagener (Hrsg.), Symbole der Macht? Aspekte mittelalterlicher und frühneuzeitlicher Architektur (2012) N. Peter Joosse, The Physician as a Rebellious Intellectual. The Book of the Two Pieces of Advice or Kitāb al-Naṣīḥatayn by cAbd al-Laṭīf ibn Yūsuf al-Baghdādī (1162–1231) (2013) Meike Pfefferkorn, Zur Semantik von rike in der Sächsischen Weltchronik. Reden über Herrschaft in der frühen deutschen Chronistik - Transforma- tionen eines politischen Schlüsselwortes (2014) Eva Spinazzè, La luce nell'architettura sacra: spazio e orientazione nelle chiese del X-XII secolo tra Romandie e Toscana. Including an English summary. Con una introduzione di Xavier Barral i Altet e di Manuela Incerti (2016) Christa Agnes Tuczay (Hrsg.), Jenseits. Eine mittelalterliche und mediävis- tische Imagination. Interdisziplinäre Ansätze zur Analyse des Unerklär- lichen (2016) Begründet von Peter Dinzelbacher Herausgegeben von Albrecht Classen LANG MEDIAEVISTIK MEDI 29-2016 271583-160x230 Br-AM PLE.indd 1 24.01.17 KW 04 09:06 Beihefte zur Mediaevistik: Band 29 2016 Andrea Grafetstätter / Sieglinde Hartmann / James Ogier (eds.) 2016 , Islands · and Cities in Medieval Myth, Literature, and History. Papers Delivered at the International Medieval Congress, Univer-sity of Leeds, in 2005, 2006, and 2007 (2011) Internationale Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Mittelalterforschung Olaf Wagener (Hrsg.), „vmbringt mit starcken turnen, murn“. -

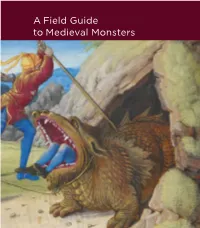

A Field Guide to Medieval Monsters Unicorns

A Field Guide to Medieval Monsters Unicorns. Griffins. Dragons. Sirens. Some of these monsters you may recognize from fairy July 7–October 6 tales, Greek and Roman mythology, or books about your favorite boy wizard. In the Middle Ages, these monsters and many more made their way onto the pages of illuminated manu- scripts. These handwritten texts, which include bibles, books of hours, and books of psalms, were often decorated with elaborate designs and images. This exhibition, Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders, explores how images of monsters played a complex role in medi- eval society and operated in a variety of ways, often instilling fear, revulsion, devotion, or wonderment. Medieval Monsters is organized by the Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Supporting Sponsor: The Womens Council of the Cleveland Museum of Art Media Sponsor: Before you start You are ready to go! Use exploring, there is some this field guide to identify monster terminology monsters you encounter you may need to know. throughout the exhibition. Anthropomorphic a creature or object having humanlike Basilisk a reptile or serpent who can Livre des merveilles du monde (Book of Marvels of the World), characteristics cause death with a glance, often described in French, c. 1460. Illuminated by the Master of the Geneva as a crested snake or as a rooster with a Boccaccio. France, Angers. Ink snake’s tail. Here, the basilisk appears in an and tempera on vellum. The Cryptozoology the study of hidden creatures, which aims to Morgan Library & Museum, image that is supposed to represent Ethiopia. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan prove the existence of beasts from folklore (1837–1913), 1911, MS M.461 (fol. -

St. Alban, Built "When Peaceable Christian Times Were Restored" (Possibly the 4Th Century) and Still in Use in Bede's Time

Welcome to OUR 18th VIRTUAL GSP class! Britain’s first martyr ST.ALBAN: WHY DO WE HONOR HIM? Presented by Charles E.Dickson,Ph.D. COLLECT FOR ALBAN, FIRST MARTYR OF BRITAIN 22 JUNE Almighty God, by whose grace and power thy holy martyr Alban triumphed over suffering and was faithful even unto death: Grant to us, who now remember him with thanksgiving, to be so faithful in our witness to thee in this world, that we may receive with him the crown of life; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. ANGLICANISM’S TUDOR BEGINNINGS The Church of England (and therefore the Episcopal Church) traces its specifically Anglican identity with its links to the State back to the Reformation. Henry VIII started the process of creating the Church of England after his split with Rome in the 1530s as he ended his marriage with Catherine of Aragon and moved on to Anne Boleyn. The first Act of Supremacy, passed by Parliament in 1534, granted Henry and subsequent monarchs Royal Supremacy, such that they were declared the Supreme Head of the Church of England. ANGLICANISM’S ANGLO-SAXON BEGINNINGS The Church of England often dates its formal foundation to St.Augustine of Canterbury’s Gregorian Mission to England in 597. Like Henry VIII this "Apostle to the English" can be considered a founder of the English Church. Augustine was the 1st and the Most Rev. Justin Welby is the 105th Archbishop of Canterbury. ANGLICANISM’S ANCIENT BEGINNINGS Actually the Church of England’s roots go back to the early church. -

October 7, 2018

Nineteenth Sunday after Trinity October 7, 2018 At 8th and N Streets NW Washington DC Seton House 1317 8th Street NW Washington DC 20001 202-999-9934 StLukesOrdinariate.com Rev. John Vidal Pastor Rev. Matthew Whitehead Assisting Priest Rev. Mr. Mark Arbeen Parish Novenas Begin This Week Deacon Pick up your holy cards on your way out of Mass this morning and pray the Novena of Thanksgiving, as well as another Novena for Guidance. Welcome to St. Luke’s at Immaculate Conception. We are delighted to have you with us. October is Stewardship Month We are a parish of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter, which was established on January 1, 2012 See the bulletin insert for more information. by Pope Benedict XVI in response to repeated requests by Anglicans seeking to become Catholic. Ordinariate parishes Mite Box Collection are fully Catholic while retaining elements of their Anglican Next Sunday is the second Sunday of the month, when we collect the heritage and traditions, including liturgical traditions. spare change you are gathering for the Building Fund. Don’t have a mite box? You can get one from the ushers after mass and MASSES: Sunday—Friday, 8:30 am start collecting. And you can always just bring up whatever spare change CONFESSIONS: Sundays & Wednesdays, you have in your pocket. No contribution is too small to matter. 7:45-8:15am Corporal Work of Mercy for October: Feeding the Hungry This month we will be assisting St. Martin of Tours Catholic Church Schedule for Immaculate Conception Church as they prepare Thanksgiving baskets with turkeys. -

Transformations in Medieval English Romance

Durham E-Theses Transformations in Medieval English Romance GOODISON, NATALIE,JAYNE How to cite: GOODISON, NATALIE,JAYNE (2017) Transformations in Medieval English Romance, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12054/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Material Abstract This thesis examines the role of transformation in medieval English romance. It explores corporeal changes of humans transformed into animals, monstrous men, loathly ladies, as well as the transformative effects of death. However, transformations could also alter one’s identity and interior states of being. Transformation in these texts is revealed to affect the body as well as the spirit. This symbiotic relationship between outward body and interior spirit is first demonstrated between two separate persons, and progresses to become localized within the one body and the same soul. -

Conflicts and Continuity in the Eleventh-Century Religious Reform: the Traditions of San Miniato Al Monte in Florence and the Or

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , July . © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./S Conflicts and Continuity in the Eleventh-Century Religious Reform: The Traditions of San Miniato al Monte in Florence and the Origins of the Benedictine Vallombrosan Order by FRANCESCO SALVESTRINI University of Florence E-mail: Francesco.salvestrini@unifi.it Studies of the ecclesiastical reform of the eleventh century have often highlighted conflict between reforming monks and simoniac clerics. This was especially true in the urban contexts of Milan and Florence, cities that played a leading role, at the time, in the history of Italian religious life. Through the presentation of an exemplary case study, this paper shows how around an important Florentine monastery, an episcopal foundation, the conflict between ‘conservatives’ and reformers did not obliterate the genesis and permanence of long-term devo- tional and cultural traditions. Although these traditions emerged in a context of conflict, they were able to overcome it and develop into a new and enduring form of religiosity that lasted from the Romanesque period to the Early Renaissance. edieval historiography has often described protagonists of the ecclesiastical reform movement of the eleventh century as M ‘revolutionaries’, in primis those who belonged to the so-called reformed Benedictine monasticism (Cluniacs, Cistercians, Camaldolese, Vallombrosans). In both early hagiographic sources and modern scholarly literature some of the founders of these religious movements (Stephen Harding, Romuald of Ravenna, John Gualberto) have taken on the roles of persecuted champions in the struggle against corrupt prelates and the Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

CABF2015 Brochure.Indd

Visit us in Booth 103 Fair Hours: Oakland Marriott City Center Friday February 6 3 p.m. - 8 p.m. 1001 Broadway, Oakland, CA Saturday February 7 11 a.m. - 7 p.m. BART Station Sunday 12th St. Oakland City Center February 8 11 a.m. - 5 p.m. A Sampling of the Illuminated Material, Incunabula, Fine Bindings, Private Press, Plate Books, Early English Works, and Other Interesting Items We’ll Have on Display at the 2015 California Antiquarian Book Fair BORDER DECORATED WITH FLOWERING VINES AND WITH All individual items in this list are octavo (between 6-10” tall) FIVE BIRDS, THE CORNERS FEATURING PORTRAITS OF FOUR except where noted. SAINTS, including Peter, two other apostles, and a cephalophore I. Illuminated Manuscript Material possibly representing Saint Denis or Saint George. $45,000 A early 15th century thoroughly Venetian Missal with extremely fine 1. A FINE VELLUM ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPT BOOK OF illumination in the style of Cristoforo Cortese and an elaborately decorated HOURS IN LATIN. (BURNE-JONES, EDWARD - HIS COPY). USE and adorned binding probably done by the monastery of San Giorgio OF PARIS. (Paris, first third of the 15th century) EXCELLENT 17TH Maggiore. (ST12776a) CENTURY RED MOROCCO, RICHLY GILT, covers with a border of repeated floral stamps within wreathed ovals, the border enclosing 3. AN EXQUISITE ILLUMINATED VELLUM MANUSCRIPT BOOK a large central panel decorated with a leafy wreath at the middle OF HOURS IN LATIN AND FRENCH, FROM THE WORKSHOP OF surrounded by a field of closely spaced fleurs-de-lys, the corner of this THE MASTER OF THE GENEVA LATINI. -

Copyright by Anna Lisa Taylor 2006

Copyright by Anna Lisa Taylor 2006 This Dissertation Committee for Anna Lisa Taylor certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Poetry, Patronage, and Politics: Epic Saints’ Lives in Western Francia, 800-1000 Committee: ____________________________ Martha Newman, Supervisor ____________________________ Alison Frazier, Supervisor ___________________________ Jennifer Ebbeler ____________________________ Brian Levack ____________________________ Marjorie Woods Poetry, Patronage, and Politics: Epic Saints’ Lives in Western Francia, 800-1000 by Anna Lisa Taylor, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2006 For my parents, Elizabeth and Bruce. Acknowledgements This dissertation was completed with all kinds of support from a large number of people. Thank you to my parents for years (and then more years) of unfailing encouragement, my long time friend and mentor Lisa Kallet for dragging me kicking and screaming to Texas, and to Al C., Mary Vance, and Samara Turner for keeping me happy and healthy. The research for this dissertation was completed with support from the Mellon Foundation, the Bibliography Society, the Medieval Academy, the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library, and a Dora Bonham award from the University of Texas. The writing was funded by a Harrington Fellowship from the University of Texas. I wish to express my utmost gratitiude to all these organizations that saw the value in manuscript research and the investigation of neglected sources. This project could not have been completed without the kindness and assistance of the librarians at the Bibliothèque nationale de France at Richilieu, the Bibliothèques municipales in Valenciennes, Douai, Rouen, Saint-Omer, and Boulogne-sur-mer, the KBR, the BAV, and the Bodleian. -

The Creation of Denis As a Cephalophoric Saint a Thesis

University of Nevada, Reno Get A Head In Life: The Creation of Denis as a Cephalophoric Saint A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Edward V. Donofrio Dr. Edward M. Schoolman/Thesis Advisor May, 2020 Copyright by Edward Donofrio 2020 All Rights Reserved NEVADA GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by Edward Donofrio Entitled Get A Head In Life: The Creation of Denis as a Cephalophoric Saint be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Edward Schoolman, Ph.D. Advisor Meredith Oda, Ph.D. Committee Member Linda Curcio, Ph.D. Committee Member Jason Fisette, Ph.D. Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D. Dean, Graduate School May 2020 i Abstract Martyrdoms by beheading are not uncommon in hagiographic narratives. In fact, it is one of the most common forms of martyrdom. In 8th century Francia, the beheading of Saint Denis became rose to national prestige. Saint Denis, the patron saint of Paris, engaged in a unique and original act. After Denis’ martyrdom, he was raised from the dead and carried his head in his hands two miles to the location where his basilica would be constructed. Thus Denis became the most famous cephalophoric - or head-bearing - saint. This study asserts the murder of Saint Boniface in 754 is directly linked to the creation of Denis as a cephalophoric saint in the later 8th century. The Franks of the 8th and early 9th centuries used the hagiographic trope of cephalophory in a politically motivated decision during the formative years before the emergence of the Frankish empire. -

View / Open Phillips Oregon 0171N 12216.Pdf

NOT DEAD BUT SLEEPING: RESURRECTING NICCOLÒ MENGHINI’S SANTA MARTINA by CAROLINE ANNE CYNTHIA PHILLIPS A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Caroline Anne Cynthia Phillips Title: Not Dead but Sleeping: Resurrecting Niccolò Menghini’s Santa Martina This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Dr. James Harper Chair Dr. Maile Hutterer Member Dr. Derek Burdette Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2018 ii © 2018 Caroline Anne Cynthia Phillips iii THESIS ABSTRACT Caroline Anne Cynthia Philips Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture June 2018 Title: Not Dead but Sleeping: Resurrecting Niccolò Menghini’s Santa Martina Niccolò Menghini’s marble sculpture of Santa Martina (ca. 1635) in the Church of Santi Luca e Martina in Rome belongs to the seventeenth-century genre of sculpture depicting saints as dead or dying. Until now, scholars have ignored the conceptual and formal concerns of the S. Martina, dismissing it as derivative of Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia (1600). This thesis provides the first thorough examination of Menghini’s S. Martina, arguing that the sculpture is critically linked to the Post-Tridentine interest in the relics of early Christian martyrs. -

Las Cantigas De Santa Maria: Thirteenth-Century Popular Culture

LAS CANTIGAS DE SANTA MARIA: THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POPULAR CULTURE AND ACTS OF SUBVERSION Jerry Coats Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2016 APPROVED: Laura Stern, Major Professor Marilyn Morris, Committee Member Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Committee Member Robert Upchurch, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of English David Holdeman, Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences Victor Prybutok, Vice Provost of the Toulouse Graduate School Coats, Jerry B. “Las Cantigas de Santa Maria”: Thirteenth-century Popular Culture and Acts of Subversion. Doctor of Philosophy (History-European History), August 2016, 273 pp., bibliography, 267 titles. Across medieval Europe, the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela in Spain traced a lattice web of popular culture. From the lowest peasant to the greatest king and churchmen, the devout walked pathways that created an economy and contributed to a social and political climate of change. Central to this impulse of piety and wanderlust was the veneration of the Virgin Mary. She was, however, not the iconic Mother of the New Testament whose character, actions, and very name are nearly absent from that first-century compilation of texts. As characterized in the words of popular songs and tales, the mariales, she was a robust saint who performed acts of healing that exceeded those miracles of Jesus described in the Bible. Unafraid and authoritative, she confronted demons and provided judgement that reached beyond the understanding and mercy of medieval codes of law. Holding out the promise of protection from physical and spiritual harm, she attracted denizens of admirers who included poets, minstrels, and troubadours like Nigel of Canterbury, John of Garland, Gonzalo de Berceo, and Gautier de Coinci.