The Slaves of the Padishah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Making Magyars, Creating Hungary: András Fáy, István Bezerédj and Ödön Beöthy’s Reform-Era Contributions to the Development of Hungarian Civil Society by Eva Margaret Bodnar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics © Eva Margaret Bodnar Spring 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract The relationship between magyarization and Hungarian civil society during the reform era of Hungarian history (1790-1848) is the subject of this dissertation. This thesis examines the cultural and political activities of three liberal oppositional nobles: András Fáy (1786-1864), István Bezerédj (1796-1856) and Ödön Beöthy (1796-1854). These three men were chosen as the basis of this study because of their commitment to a two- pronged approach to politics: they advocated greater cultural magyarization in the multiethnic Hungarian Kingdom and campaigned to extend the protection of the Hungarian constitution to segments of the non-aristocratic portion of the Hungarian population. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 5, no. 1 (2016): 5–21 Martyn Rady Nonnisi in sensu legum? Decree and Rendelet in Hungary (1790–1914) The Hungarian “constitution” was never balanced, for its sovereigns possessed a supervisory jurisdiction that permitted them to legislate by decree, mainly by using patents and rescripts. Although the right to proceed by decree was seldom abused by Hungary’s Habsburg rulers, it permitted the monarch on occasion to impose reforms in defiance of the Diet. Attempts undertaken in the early 1790s to hem in the ruler’s power by making the written law both fixed and comprehensive were unsuccessful. After 1867, the right to legislate by decree was assumed by Hungary’s government, and ministerial decree or “rendelet” was used as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Not only could rendelets be used to fill in gaps in parliamentary legislation, they could also be used to bypass parliament and even to countermand parliamentary acts, sometimes at the expense of individual rights. The tendency remains in Hungary for its governments to use discretionary administrative instruments as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Keywords: constitution, decree, patent, rendelet, legislation, Diet, Parliament In 1792, the Transylvanian Diet opened in the assembly rooms of Kolozsvár (today Cluj, Romania) with a trio, sung by the three graces, each of whom embodied one of the three powers identified by Montesquieu as contributing to a balanced constitution.1 The Hungarian constitution, however, was never balanced. The power attached to the executive was always the greatest. Attempts to hem in the executive, however, proved unsuccessful. During the later nineteenth century, the legislature surrendered to ministers a large share of its legislative capacity, with the consequence that ministerial decree or rendelet often took the place of statute law. -

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: the Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: The Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918 MICHAEL LAURENCE MILLER WO OF THE MOST ICONIC PHOTOS of the 1956 Hungarian revolution involve a colossal statue of Stalin, erected in 1951 and toppled on the first day of the anti-Soviet uprising. TOne of these pictures shows Stalin’s decapitated head, abandoned in the street as curious pedestrians amble by. The other shows a tall stone pedestal with nothing on it but a lonely pair of bronze boots. Situated near Heroes’ Square, Hungary’s national pantheon, the Stalin statue had served as a symbol of Hungary’s subjugation to the Soviet Union; and its ceremonious and deliberate destruction provided a poignant symbol for the fall of Stalinism. Thirty-eight years before, at the beginning of an earlier Hungarian revolution, another despised statue was toppled in Budapest, also marking a break from foreign subjugation, albeit to a different power. Unlike the Stalin statue, which stood for only five years, this statue—the so-called Hentzi Monument—had been “a splinter in the eye of the [Hungarian] nation” for sixty-six years. Perceived by many Hungarians as a symbol of “national humiliation” at the hands of the Habsburgs, the Hentzi Monument remained mired in controversy from its unveiling in 1852 until its destruction in 1918. The object of street demonstrations and parliamentary disorder in 1886, 1892, 1898, and 1899, and the object of a failed “assassination” attempt in 1895, the Hentzi Monument was even implicated in the fall of a Hungarian prime minister. -

A MUSLIM MISSIONARY in MEDIAEVAL KASHMIR a MUSLIM MISSIONARY in MEDIAEVAL KASHMIR (Being the English Translation of Tohfatuíl-Ahbab)

A MUSLIM MISSIONARY IN MEDIAEVAL KASHMIR A MUSLIM MISSIONARY IN MEDIAEVAL KASHMIR (Being the English translation of Tohfatuíl-Ahbab) by Muhammad Ali Kashmiri English translation and annotations by KASHINATH PANDIT ASIAN-EURASIAN HUMAN RIGHTS FORUM New Delhi iv / ATRAVAILS MUSLIM MISSIONARYOF A KASHMIR IN FREEDOMMEDIAEVAL FIGHTER KASHMIR This book is the English translation of a Farsi manuscript, Tohfatuíl- Ahbab, persumably written in AD 1640. A transcript copy of the manuscript exists in the Research and Publications Department of Jammu and Kashmir State under Accession Number 551. © KASHINATH PANDIT First Published 2009 Price: Rs. 400.00 Published by Eurasian Human Rights Forum, E-241, Sarita Vihar, New Delhi ñ 110 076 (INDIA). website: www.world-citizenship.org Printed at Salasar Imaging Systems, C-7/5, Lawrence Road Indl. Area, Delhi ñ 110 035. INTRODUCTIONCONTENTS //v v For the historians writing on Mediaeval India vi / ATRAVAILS MUSLIM MISSIONARYOF A KASHMIR IN FREEDOMMEDIAEVAL FIGHTER KASHMIR INTRODUCTIONCONTENTS / vii Contents Acknowledgement ix Introduction xi-lxxx Chapter I. Araki and Nurbakhshi Preceptors 1-65 Chapter II. Arakiís first Visit to Kashmir: His Miracles, Kashmiris, and Arakiís Return 66-148 Chapter III. Arakiís Return to Iran 149-192 Part I: Acrimony of the people of Khurasan towards Shah Qasim 149-161 Part II: In service of Shah Qasim 161-178 Part III: To Kashmir 178-192 Chapter IV. Mission in Kashmir 193-278 Part I: Stewardship of Hamadaniyyeh hospice 193-209 Part II: Arakiís mission of destroying idols and temples of infidels 209-278 Chapter V. Arakiís Munificence 279-283 Index 284-291 viii / ATRAVAILS MUSLIM MISSIONARYOF A KASHMIR IN FREEDOMMEDIAEVAL FIGHTER KASHMIR INTRODUCTIONCONTENTS /ix/ ix 1 Acknowledgement I am thankful to Dr. -

An Introduction to David Morgan

An Introduction to David Morgan David Morgan The working title for this festschrift was ‘Papers for the Padishah’. It was discarded for the sake of propriety as well as the well-known decree that all academic books must include a colon, a decree which some would say is worthy of Chinggis Khan himself. Nonetheless, I believe it is fair to consider David O. Morgan the Padishah of the study of the Mongol Empire. David, ever humble, would simply wave this title away and offer another scholar the throne. In this sense, David is like Ogodei Khan—generous, well-liked by all, and he laid much of the modern foundations for the study of the Mongols. Yet, David, like Ghazan Khan, always kept one foot firmly in Iranian Studies as well, thus giving him claim to the title of Padishah. David’s similarity to the Mongols does not end there, however, as he carved his own intellectual empire. The foundations of Professor Morgan’s empire began when he acquired Michael Prawdin’s The Mongol Empire: Its Rise and Legacy as a prize at Rugby. From there he studied at Oxford before venturing into the field of secondary education. He then proceeded to earn his doctorate from the School of Oriental and African Studies in the University of London, where he studied Persian under the instruction of the late Ann K. S. Lambton. As Persian was not offered at Wisconsin when I was a student, he tutored me in his book-lined study, complete with a roaring fire in the fireplace. While I struggled through it, he often noted that that he was Lambton’s second worse student—the worst being a future ambassador to Iran, of course. -

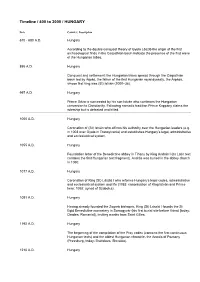

Asin Indicate the Presence of the First Wave of the Hungarian Tribes

Timeline / 400 to 2000 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 670 - 680 A.D. Hungary According to the double conquest theory of Gyula László the origin of the first archaeological finds in the Carpathian basin indicate the presence of the first wave of the Hungarian tribes. 895 A.D. Hungary Conquest and settlement: the Hungarian tribes spread through the Carpathian basin led by Árpád, the father of the first Hungarian royal dynasty, the Árpáds, whose first king was (St) István (1000–38). 997 A.D. Hungary Prince Géza is succeeded by his son István who continues the Hungarian conversion to Christianity. Following nomadic tradition Prince Koppány claims the rulership but is defeated and killed. 1000 A.D. Hungary Coronation of (St) István who affirms his authority over the Hungarian leaders (e.g. in 1003 over Gyula in Transylvania) and establishes Hungary’s legal, administrative and ecclesiastical system. 1055 A.D. Hungary Foundation letter of the Benedictine abbey in Tihany by King András I (its Latin text contains the first Hungarian text fragment). András was buried in the abbey church in 1060. 1077 A.D. Hungary Coronation of King (St) László I who reforms Hungary’s legal codes, administrative and ecclesiastical system and life (1083: canonisation of King István and Prince Imre; 1092: synod of Szabolcs). 1091 A.D. Hungary Having already founded the Zagreb bishopric, King (St) László I founds the St Egid Benedictine monastery in Somogyvár (his first burial site before Várad [today: Oradea, Romania]), inviting monks from Saint Gilles. 1192 A.D. Hungary The beginning of the compilation of the Pray codex (contains the first continuous Hungarian texts) and the oldest Hungarian chronicle, the Annals of Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava, Slovakia). -

Persia: Place and Idea

1 Persia: Place and Idea Persia/Persians and Iran/Iranians “Persia” is not easily located with any geographic specificity, nor can its people, the Persians, be easily categorized. In the end Persia and the Persians are as much metaphysical notions as a place or a people. Should it be Iran and the Iranians? Briefly, “Persia/Persians” is seldom used today, except in the United Kingdom or when referring to ancient Iran/Iranians – c. sixth century bc to the third century ad. Riza Shah (1926–1941) decreed in 1935 that Iran be used exclusively in official and diplomatic correspondence. Iran was the term commonly used in Iran and by Iranians, except from the seventh to the thirteenth centuries. Fol- lowing the Second World War, oil nationalization, the Musaddiq crisis, and subsequent greater sensitivity to Iranian nationalism, the designa- tion Iran/Iranian became widely used in the west. Until recently the use of Persia/Persians was often rejected among Iranians themselves. Iran/Iranian also had its own hegemonic dimension, especially from the experience of some of Iran’s multi-ethnic population. The usage of Persia/Persian, however, was revived by Iranian expatriates in the post- 1979 era of the Islamic Republic of Iran. This common usage among them represents an attempt on their part to be spared the opprobrium of “Iran” and its recent association with revolution, “terrorism,” hostages, and “fundamentalism,” while Persia/Persian suggested to them an ancient glory and culture – a less threatening contemporary political identity. Nevertheless, the political ramifications of either Persia or Iran cannot be escaped. Above all, the history of Persia/Iran is the history of the interaction between place and the peoples who have lived and who currently live there. -

The Philanthropies of the Sultan's Daughter Ayşe Sultan from the Beginning of the 17Th Century, and Her Waqf's Accounting R

Muhasebe ve Finans Tarihi Araştırmaları Dergisi Temmuz 2016 (11) THE PHILANTHROPIES OF THE SULTAN’S DAUGHTER AYŞE SULTAN FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE 17TH CENTURY, AND HER WAQF’S ACCOUNTING RECORDS(*) Dr. Fatma Şensoy Marmara University – Turkey Abstract Awqaf (waqf as singular) are founded as charities that have certain laws and that are sustainable, such as fund-dependant, decentralised, voluntary democratic and nongovernmental organizations. At the same time, they are financial institutions that deal with social security, educational, cultural, religious affairs, public works, social aid and health investments. They are inspected by the government despite their financial and administrative autonomies, and these institutions have survived for centuries and provided services to society and enjoyed great monetary success. It is possible to read about their auditing and information about accounting in the Ottoman financial tradition from the books of accounts kept in the awqaf (foundations). The waqf culture has survived for centuries primarily because of this efficient, inspecting recording order. Ayşe Sultan was the daughter of Sultan Murad III (1574-1595) and Safiye (*) Bu bildiri, 25 - 27 Haziran 2016 tarihlerinde Pescara (İtalya)’da yapılan 14. Dünya Muhasebe Tariçileri Kongresinde İngilizce olarak sunulmuştur. 125 Accounting and Financial History Research Journal July 2016 (11) Sultan. She dedicated her assets to a waqf which was setup by her husband Ghazi Ibrahim Paşa and herself. The tombs and fountain still survive. The waqf which was founded at the beginning of the 17th century survived for ages. The accounting books of the waqf reveal the accounting culture of social aid at that time. The books are recorded by siyaqat script and numbers and used the Merdiven (stair) method. -

A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699

A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699 Edited by Gábor Almási, Szymon Brzezi ski, Ildikó Horn, Kees Teszelszky and Áron Zarnóczki Volume 2 Diplomacy, Information Flow and Cultural Exchange Edited by Szymon Brzezi ski and Áron Zarnóczki A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699; Volume 2 Diplomacy, Information Flow and Cultural Exchange, Edited by Szymon Brzezi ski and Áron Zarnóczki This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Szymon Brzezi ski, Áron Zarnóczki and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6687-3, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6687-3 CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Zone of ConflictZone of Exchange: Introductory Remarks on Early Modern Hungary in Diplomatic and Information Networks ....................... 1 Szymon Brzezi ski I. Hungary and Transylvania in the Early Modern Diplomatic and Information Networks Re-Orienting a Renaissance Diplomatic Cause Célèbre: The 1541 Rincón-Fregoso Affair .............................................................. -

General Historical Survey

General Historical Survey 1521-1525 tention to the Knights Hospitallers on Rhodes (which capitulated late During the later years of his reign Sultan Selīm I was engaged militar- in 1522 after a long siege). ily against the Safavid state in Iran and the Mamluk sultanate in Syria and Egypt, so Central Europe felt relatively safe. King Lajos II of Hun- gary was only ten years old when, in 1516, he succeeded to the throne 1526-1530 and was placed under guardianship. In 1506 he had already been be- Between 1523 and 1525 Süleyman and his Grand Vizier and favour- trothed to Maria, the sister of Emperor Ferdinand, by the Pact of Wie- ite, Ibrahim Pasha (d. 942/1536), were chiefly engaged in settling ner Neustadt, where a royal double marriage was arranged between the affairs of Egypt. His second campaign into Hungary, which was the Habsburg and Jagiello dynasties. The government of Hungary was launched in April 1526, led ultimately, after a slow and difficult march, entrusted to a State Council, a group of men who were interested only to a military encounter known as the first Battle of Mohács. It was in enriching themselves. In a word: the crown had been reduced to fought on 20 Zilkade 932/29 August 1526 on the plain of Mohács, west political insignificance; the country was in chaos, the treasury empty, of the Danube in southern Hungary, near the present-day intersection the army virtually non-existent and the system of defence utterly ne- of Hungary, Croatia and Serbia. Both Süleyman and Lajos II partic- glected. -

Role of Persians at the Mughal Court: a Historical

ROLE OF PERSIANS AT THE MUGHAL COURT: A HISTORICAL STUDY, DURING 1526 A.D. TO 1707 A.D. PH.D THESIS SUBMITTED BY, MUHAMMAD ZIAUDDIN SUPERVISOR: PROF. DR. MUNIR AHMED BALOCH IN THE AREA STUDY CENTRE FOR MIDDLE EAST & ARAB COUNTRIES UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN QUETTA, PAKISTAN. FOR THE FULFILMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY 2005 DECLARATION BY THE CANDIDATE I, Muhammad Ziauddin, do solemnly declare that the Research Work Titled “Role of Persians at the Mughal Court: A Historical Study During 1526 A.D to 1707 A.D” is hereby submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy and it has not been submitted elsewhere for any Degree. The said research work was carried out by the undersigned under the guidance of Prof. Dr. Munir Ahmed Baloch, Director, Area Study Centre for Middle East & Arab Countries, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan. Muhammad Ziauddin CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. Muhammad Ziauddin has worked under my supervision for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. His research work is original. He fulfills all the requirements to submit the accompanying thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Munir Ahmed Research Supervisor & Director Area Study Centre For Middle East & Arab Countries University of Balochistan Quetta, Pakistan. Prof. Dr. Mansur Akbar Kundi Dean Faculty of State Sciences University of Balochistan Quetta, Pakistan. d DEDICATED TO THE UNFORGETABLE MEMORIES OF LATE PROF. MUHAMMAD ASLAM BALOCH OF HISTORY DEPARTMENT UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA PAKISTAN e ACKNOWLEDGMENT First of all I must thank to Almighty Allah, who is so merciful and beneficent to all of us, and without His will we can not do anything; it is He who guide us to the right path, and give us sufficient knowledge and strength to perform our assigned duties. -

Legitimizing the Ottoman Sultanate: a Framework for Historical Analysis

LEGITIMIZING THE OTTOMAN SULTANATE: A FRAMEWORK FOR HISTORICAL ANALYSIS Hakan T. K Harvard University Why Ruled by Them? “Why and how,” asks Norbert Elias, introducing his study on the 18th-century French court, “does the right to exercise broad powers, to make decisions about the lives of millions of people, come to reside for years in the hands of one person, and why do those same people persist in their willingness to abide by the decisions made on their behalf?” Given that it is possible to get rid of monarchs by assassination and, in extreme cases, by a change of dynasty, he goes on to wonder why it never occurred to anyone that it might be possible to abandon the existing form of government, namely the monarchy, entirely.1 The answers to Elias’s questions, which pertain to an era when the state’s absolutism was at its peak, can only be found by exposing the relationship between the ruling authority and its subjects. How the subjects came to accept this situation, and why they continued to accede to its existence, are, in essence, the basic questions to be addressed here with respect to the Ottoman state. One could argue that until the 19th century political consciousness had not yet gone through the necessary secularization process in many parts of the world. This is certainly true, but regarding the Ottoman population there is something else to ponder. The Ottoman state was ruled for Most of the ideas I express here are to be found in the introduction to my doc- toral dissertation (Bamberg, 1997) in considering Ottoman state ceremonies in the 19th century.