A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Making Magyars, Creating Hungary: András Fáy, István Bezerédj and Ödön Beöthy’s Reform-Era Contributions to the Development of Hungarian Civil Society by Eva Margaret Bodnar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics © Eva Margaret Bodnar Spring 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract The relationship between magyarization and Hungarian civil society during the reform era of Hungarian history (1790-1848) is the subject of this dissertation. This thesis examines the cultural and political activities of three liberal oppositional nobles: András Fáy (1786-1864), István Bezerédj (1796-1856) and Ödön Beöthy (1796-1854). These three men were chosen as the basis of this study because of their commitment to a two- pronged approach to politics: they advocated greater cultural magyarization in the multiethnic Hungarian Kingdom and campaigned to extend the protection of the Hungarian constitution to segments of the non-aristocratic portion of the Hungarian population. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 5, no. 1 (2016): 5–21 Martyn Rady Nonnisi in sensu legum? Decree and Rendelet in Hungary (1790–1914) The Hungarian “constitution” was never balanced, for its sovereigns possessed a supervisory jurisdiction that permitted them to legislate by decree, mainly by using patents and rescripts. Although the right to proceed by decree was seldom abused by Hungary’s Habsburg rulers, it permitted the monarch on occasion to impose reforms in defiance of the Diet. Attempts undertaken in the early 1790s to hem in the ruler’s power by making the written law both fixed and comprehensive were unsuccessful. After 1867, the right to legislate by decree was assumed by Hungary’s government, and ministerial decree or “rendelet” was used as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Not only could rendelets be used to fill in gaps in parliamentary legislation, they could also be used to bypass parliament and even to countermand parliamentary acts, sometimes at the expense of individual rights. The tendency remains in Hungary for its governments to use discretionary administrative instruments as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Keywords: constitution, decree, patent, rendelet, legislation, Diet, Parliament In 1792, the Transylvanian Diet opened in the assembly rooms of Kolozsvár (today Cluj, Romania) with a trio, sung by the three graces, each of whom embodied one of the three powers identified by Montesquieu as contributing to a balanced constitution.1 The Hungarian constitution, however, was never balanced. The power attached to the executive was always the greatest. Attempts to hem in the executive, however, proved unsuccessful. During the later nineteenth century, the legislature surrendered to ministers a large share of its legislative capacity, with the consequence that ministerial decree or rendelet often took the place of statute law. -

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: the Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: The Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918 MICHAEL LAURENCE MILLER WO OF THE MOST ICONIC PHOTOS of the 1956 Hungarian revolution involve a colossal statue of Stalin, erected in 1951 and toppled on the first day of the anti-Soviet uprising. TOne of these pictures shows Stalin’s decapitated head, abandoned in the street as curious pedestrians amble by. The other shows a tall stone pedestal with nothing on it but a lonely pair of bronze boots. Situated near Heroes’ Square, Hungary’s national pantheon, the Stalin statue had served as a symbol of Hungary’s subjugation to the Soviet Union; and its ceremonious and deliberate destruction provided a poignant symbol for the fall of Stalinism. Thirty-eight years before, at the beginning of an earlier Hungarian revolution, another despised statue was toppled in Budapest, also marking a break from foreign subjugation, albeit to a different power. Unlike the Stalin statue, which stood for only five years, this statue—the so-called Hentzi Monument—had been “a splinter in the eye of the [Hungarian] nation” for sixty-six years. Perceived by many Hungarians as a symbol of “national humiliation” at the hands of the Habsburgs, the Hentzi Monument remained mired in controversy from its unveiling in 1852 until its destruction in 1918. The object of street demonstrations and parliamentary disorder in 1886, 1892, 1898, and 1899, and the object of a failed “assassination” attempt in 1895, the Hentzi Monument was even implicated in the fall of a Hungarian prime minister. -

Asin Indicate the Presence of the First Wave of the Hungarian Tribes

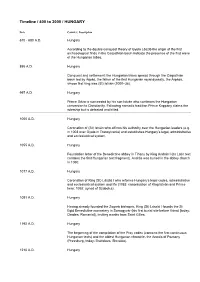

Timeline / 400 to 2000 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 670 - 680 A.D. Hungary According to the double conquest theory of Gyula László the origin of the first archaeological finds in the Carpathian basin indicate the presence of the first wave of the Hungarian tribes. 895 A.D. Hungary Conquest and settlement: the Hungarian tribes spread through the Carpathian basin led by Árpád, the father of the first Hungarian royal dynasty, the Árpáds, whose first king was (St) István (1000–38). 997 A.D. Hungary Prince Géza is succeeded by his son István who continues the Hungarian conversion to Christianity. Following nomadic tradition Prince Koppány claims the rulership but is defeated and killed. 1000 A.D. Hungary Coronation of (St) István who affirms his authority over the Hungarian leaders (e.g. in 1003 over Gyula in Transylvania) and establishes Hungary’s legal, administrative and ecclesiastical system. 1055 A.D. Hungary Foundation letter of the Benedictine abbey in Tihany by King András I (its Latin text contains the first Hungarian text fragment). András was buried in the abbey church in 1060. 1077 A.D. Hungary Coronation of King (St) László I who reforms Hungary’s legal codes, administrative and ecclesiastical system and life (1083: canonisation of King István and Prince Imre; 1092: synod of Szabolcs). 1091 A.D. Hungary Having already founded the Zagreb bishopric, King (St) László I founds the St Egid Benedictine monastery in Somogyvár (his first burial site before Várad [today: Oradea, Romania]), inviting monks from Saint Gilles. 1192 A.D. Hungary The beginning of the compilation of the Pray codex (contains the first continuous Hungarian texts) and the oldest Hungarian chronicle, the Annals of Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava, Slovakia). -

General Historical Survey

General Historical Survey 1521-1525 tention to the Knights Hospitallers on Rhodes (which capitulated late During the later years of his reign Sultan Selīm I was engaged militar- in 1522 after a long siege). ily against the Safavid state in Iran and the Mamluk sultanate in Syria and Egypt, so Central Europe felt relatively safe. King Lajos II of Hun- gary was only ten years old when, in 1516, he succeeded to the throne 1526-1530 and was placed under guardianship. In 1506 he had already been be- Between 1523 and 1525 Süleyman and his Grand Vizier and favour- trothed to Maria, the sister of Emperor Ferdinand, by the Pact of Wie- ite, Ibrahim Pasha (d. 942/1536), were chiefly engaged in settling ner Neustadt, where a royal double marriage was arranged between the affairs of Egypt. His second campaign into Hungary, which was the Habsburg and Jagiello dynasties. The government of Hungary was launched in April 1526, led ultimately, after a slow and difficult march, entrusted to a State Council, a group of men who were interested only to a military encounter known as the first Battle of Mohács. It was in enriching themselves. In a word: the crown had been reduced to fought on 20 Zilkade 932/29 August 1526 on the plain of Mohács, west political insignificance; the country was in chaos, the treasury empty, of the Danube in southern Hungary, near the present-day intersection the army virtually non-existent and the system of defence utterly ne- of Hungary, Croatia and Serbia. Both Süleyman and Lajos II partic- glected. -

Of Personal Names*

Index of Personal Names* Aba, Amádé, palatine of Hungary 330 Arnold of Lübeck, chronicler 84, 99, 348 Adalbert, bishop of Prague, saint 134, Árpád, grand prince of the Magyars 74, 101, 136, 346 111–112, 214 Aeneas, mythical figure 102 Artemios, saint 242 Agnes of Bohemia, daughter of King Arthur, legendary king 92 Ottokar i, saint 548 Ascanio Centario, chronicler 502 Aimoin, chronicler 102 Attila, leader of the Huns 76, 84, 94, 96–101, Ákos Master, chronicler 78 103, 106–107, 109, 113–114, 348 Albert ii, duke of Austria 354 Augustine Moravus of Olomouc, Albert of Wittelsbach, duke of Bavaria 357 humanist 478 Albert, duke of Austria, later king of Augustus, Roman emperor 477 Hungary 354 Averulino, Antonio, architect 490, 491, 492 Alberti, Leon Battista, architect 474fn Alexander the Great, Ancient ruler 477 Bakács, István 62fn, 66 Álmos, brother of King Coloman, prince 118 Bakóc, Tamás, archbishop of Esztergom 514, Álmos, prince of the Magyars 101 521 Andreas, prior of the Buda Carmelite Bandini, Francesco, humanist 479, 482, 484, friary 244 486, 487fn, 488–489 Andrew ii, king of Hungary 85–86, 143, 205, Bánfi family 316 324, 349 Barbara of Cilli, queen consort to Sigismund, Andrew iii, king of Hungary 122, 144, 172–173, Holy Roman emperor 192, 460 182, 208, 281, 324, 328–330, 374, 549 Basil of Caesarea, theologian, saint 477, Andrew-Zoerard, hermit, saint 233 478 Anna of Schweidnitz (Świdnica), queen Bátori, István, regent of Hungary 339, 498, consort to Charles iv, Holy Roman 515fn, 516–517, 522 emperor 354 Bátori, Miklós, humanist, bishop -

Timeline / 1500 to 2000 / HUNGARY

Timeline / 1500 to 2000 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 1514 A.D. Hungary Unsuccesful peasant revolt led by György Dózsa. The presentation to the Hungarian Parliament of the Tripartitum, a collection of Hungarian unwritten laws compiled by jurist István Werb#czy (published Vienna, 1518). 1522 A.D. Hungary The wedding of King Lajos II and Mary Habsburg (Mary leaves Hungary after the deaths of Lajos II and as Mary of Hungary later becomes the governor of the Low Countries). 1526 A.D. Hungary The Battle of Mohács: the 75–80 000 Turkish soldiers defeat the Hungarian army of 25,000 men. King Lajos II dies. Both János I (Szapolyai) and Ferdinand I became Hungarian kings. 1541 A.D. Hungary Sulayman I the Great occupies Buda. Hungary torn into three parts: Turkish vilajet (province); Upper Hungary under Ferdinand I; the rest under Queen Isabella and János II (János Zsigmond), son of the Queen and János I. 1552 A.D. Hungary Turks occupy several Hungarian fortresses in the new Turkish wars. At the siege of Eger fewer than 2,000 Hungarians led by István Dobó triumph over the attacking 60–70,000 Turks. 1566 A.D. Hungary Sultan Sulayman I besieges Szigetvár defended by Count Miklós Zrínyi who getting no help and with heavy odds against him dies with his soldiers in a sortie. The Sultan had died two days earlier. 1568 A.D. Hungary The Peace Treaty of Drinápoly (Adrianapolis). Bálint Bakfark (Valentin Greff Bakfark) whose lute pieces were published in Lyon (1552) lives at the Transylvanian princely court (in 1572 moves to Padua). -

The Budapest Chain Bridge

The Budapest Chain Bridge Amelie Lanier, author of a book on the Viennese banker, Georg Sina, recalls the building of a landmark which links Sina to his arch-rival Salomon von Rothschild The pontoon bridge across the Danube, for centuries the only link between Buda and Pest (Duna Muzeum, Esztergom) The building of the Chain Bridge which connects Buda to Pest is first and foremost connected with the name of Count Istvan (Stephen) Széchenyi (1791-1860), remembered today by his fellow countrymen as the “Greatest Hungarian”. His father Ferenc (Francis) had already distinguished himself by his patriotic convictions and deeds; his name is connected with the foundation of the Hungarian National Library, for example. At the beginning of his career, Istvan led the typical life of a Hungarian nobleman of his time: he joined the army and lived a lavish and rather superficial life in the palaces and ballrooms of Vienna and Budapest. But in the early 1820s he began to change his attitude towards society, under the influence of two people he came to know at the time: his future wife, Crescentia von Seilern, and the cleric Stanislaus Albach. The latter impressed upon Széchenyi the idea that God had chosen every man to fulfil a special task in life. Széchenyi’s love for Crescentia, whom he wanted to convince of his worth, led to his choice of a life’s work: to become the benefactor of Hungary by modernising it in every possible sphere and to raise it to the level of other, more 30 developed European countries. His model was England, and this it remained till the end of his life. -

A Divided Hungary in Europe

A Divided Hungary in Europe A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699 Edited by Gábor Almási, Szymon Brzeziński, Ildikó Horn, Kees Teszelszky and Áron Zarnóczki Volume 2 Diplomacy, Information Flow and Cultural Exchange Edited by Szymon Brzeziński and Áron Zarnóczki A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699; Volume 2 – Diplomacy, Information Flow and Cultural Exchange, Edited by Szymon Brzeziński and Áron Zarnóczki This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Szymon Brzeziński, Áron Zarnóczki and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6687-3, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6687-3 CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Zone of Conflict—Zone of Exchange: Introductory Remarks on Early Modern Hungary in Diplomatic and Information Networks ....................... 1 Szymon Brzeziński I. Hungary and Transylvania in the Early Modern Diplomatic and Information Networks Re-Orienting a Renaissance Diplomatic Cause Célèbre: The 1541 Rincón-Fregoso -

Timeline / 400 to 1725 / HUNGARY

Timeline / 400 to 1725 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 670 - 680 A.D. Hungary According to the double conquest theory of Gyula László the origin of the first archaeological finds in the Carpathian basin indicate the presence of the first wave of the Hungarian tribes. 895 A.D. Hungary Conquest and settlement: the Hungarian tribes spread through the Carpathian basin led by Árpád, the father of the first Hungarian royal dynasty, the Árpáds, whose first king was (St) István (1000–38). 997 A.D. Hungary Prince Géza is succeeded by his son István who continues the Hungarian conversion to Christianity. Following nomadic tradition Prince Koppány claims the rulership but is defeated and killed. 1000 A.D. Hungary Coronation of (St) István who affirms his authority over the Hungarian leaders (e.g. in 1003 over Gyula in Transylvania) and establishes Hungary’s legal, administrative and ecclesiastical system. 1055 A.D. Hungary Foundation letter of the Benedictine abbey in Tihany by King András I (its Latin text contains the first Hungarian text fragment). András was buried in the abbey church in 1060. 1077 A.D. Hungary Coronation of King (St) László I who reforms Hungary’s legal codes, administrative and ecclesiastical system and life (1083: canonisation of King István and Prince Imre; 1092: synod of Szabolcs). 1091 A.D. Hungary Having already founded the Zagreb bishopric, King (St) László I founds the St Egid Benedictine monastery in Somogyvár (his first burial site before Várad [today: Oradea, Romania]), inviting monks from Saint Gilles. 1192 A.D. Hungary The beginning of the compilation of the Pray codex (contains the first continuous Hungarian texts) and the oldest Hungarian chronicle, the Annals of Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava, Slovakia). -

Download Complete File

Hungarian Historical Review 5, no. 1 (2016): 151–221 BOOK REVIEWS Das Preßburger Protocollum Testamentorum 1410 (1427)–1529, Vol. 1. 1410–1487. Edited by Judit Majorossy and Katalin Szende. (Fontes rerum Austriacarum, 3. Abteilung, Fontes iuris 21/1.) Vienna: Böhlau, 2010. 535 pp. Das Preßburger Protocollum Testamentorum 1410 (1427)–1529, Vol. 2. 1487–1529. Edited by Judit Majorossy und Katalin Szende. (Fontes iuris, Geschichtsquelle zum österreichen Recht, 21/2.) Vienna: Böhlau, 2014. 572 pp. The use of late medieval testaments as sources in the study of legal issues, economy, culture and everyday life has been popular for some time now. In noble, ecclesiastical and urban settings, this type of source material offers a large pool of information on everyday life, economic and social ties, religious piety, understandings of the afterlife, provisional mechanisms, etc. In recent decades, a good number of collections of last wills originating from Bohemia and Moravia, Hungary, Austria and Dalmatia have been edited and analyzed. Apart from Hungary, intensive research has also been conducted in Bohemia and Moravia, where the last wills from the cities of Prague, Olomouc, Pilsen and Tabor were edited and analyzed. Well-preserved testament collections of Dalmatian cities such as Zadar, Split, Trogir and Dubrovnik are all frequently consulted by scholars. In Austria, the evaluation of late medieval wills has been intensified with the editions of the collections of Vienna, Wiener Neustadt and, recently, Korneuburg. In the 1980s, Gerhard Jaritz, member of the Institute of Medieval Material Culture in Krems and professor at the Central European University in Budapest, initiated the edition of the collection of legal instructions known as Wiener Stadtbücher, which also contain a large number of wills. -

Political Relations Between the Counts of Blagaj and King Sigismund of Luxemburg*

Review of Croatian History 11/2015, no. 1, 7 - 46 UDK: 929.52Babonić 929.7(497.5)“13/14’’ Izvorni znanstveni članak Received: May 6, 2015 Accepted: October 18, 2015 IN THE SERVICE OF THE MIGHTY KING: POLITICAL RELATIONS BETWEEN THE COUNTS OF BLAGAJ AND KING SIGISMUND OF LUXEMBURG* Hrvoje KEKEZ** The Counts of Blagaj were descendants of the noble Babonić family, which was one of the most powerful magnate families not only in medieval Slavonia, but in the whole medieval Realm of Saint Stephen (Kingdom of Hungary-Croatia), during the second half of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century. While the second half of the 14th century represents the period of their decline, the same cannot be said of the very end of the 14th and the first four decades of the 15th century, which was when King Sigismund of Luxemburg was on the Hungarian-Croatian throne. The latter period was significantly marked by the dynamic and not always beneficial relations between the Counts of Blagaj and King Sigismund of Luxemburg. Therefore, the main goal of this paper is to analyse various questions concerning the political relations between the Counts of Blagaj and King Sigismund of Luxemburg during his long reign as the king of the Realm of Saint Stephen. First of all, it shall be analysed how resolute and firm the Counts of Blagaj were as opponents of King Sigismund in the last decade of the 14th century, that is, during the period of his constant abject struggle to gain and keep the Hungarian-Croatian throne.