Timeline / 400 to 1725 / HUNGARY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Alberta

University of Alberta Making Magyars, Creating Hungary: András Fáy, István Bezerédj and Ödön Beöthy’s Reform-Era Contributions to the Development of Hungarian Civil Society by Eva Margaret Bodnar A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics © Eva Margaret Bodnar Spring 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract The relationship between magyarization and Hungarian civil society during the reform era of Hungarian history (1790-1848) is the subject of this dissertation. This thesis examines the cultural and political activities of three liberal oppositional nobles: András Fáy (1786-1864), István Bezerédj (1796-1856) and Ödön Beöthy (1796-1854). These three men were chosen as the basis of this study because of their commitment to a two- pronged approach to politics: they advocated greater cultural magyarization in the multiethnic Hungarian Kingdom and campaigned to extend the protection of the Hungarian constitution to segments of the non-aristocratic portion of the Hungarian population. -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

A Concise History of Hungary

A Concise History of Hungary MIKLÓS MOLNÁR Translated by Anna Magyar published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru, UnitedKingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org Originally publishedin French as Histoire de la Hongrie by Hatier Littérature Générale 1996 and© Hatier Littérature Générale First publishedin English by Cambridge University Press 2001 as A Concise History of Hungary Reprinted 2003 English translation © Cambridge University Press 2001 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception andto the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. Printedin the UnitedKingdomat the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Monotype Sabon 10/13 pt System QuarkXPress™ [se] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 0 521 66142 0 hardback isbn 0 521 66736 4 paperback CONTENTS List of illustrations page viii Acknowledgements xi Chronology xii 1 from the beginnings until 1301 1 2 grandeur and decline: from the angevin kings to the battle of mohács, 1301–1526 41 3 a country under three crowns, 1526–1711 87 4 vienna and hungary: absolutism, reforms, revolution, 1711–1848/9 139 5 rupture, compromise and the dual monarchy, 1849–1919 201 6 between the wars 250 7 under soviet domination, 1945–1990 295 8 1990, a new departure 338 Bibliographical notes 356 Index 357 ILLUSTRATIONS plates 11. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 5, no. 1 (2016): 5–21 Martyn Rady Nonnisi in sensu legum? Decree and Rendelet in Hungary (1790–1914) The Hungarian “constitution” was never balanced, for its sovereigns possessed a supervisory jurisdiction that permitted them to legislate by decree, mainly by using patents and rescripts. Although the right to proceed by decree was seldom abused by Hungary’s Habsburg rulers, it permitted the monarch on occasion to impose reforms in defiance of the Diet. Attempts undertaken in the early 1790s to hem in the ruler’s power by making the written law both fixed and comprehensive were unsuccessful. After 1867, the right to legislate by decree was assumed by Hungary’s government, and ministerial decree or “rendelet” was used as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Not only could rendelets be used to fill in gaps in parliamentary legislation, they could also be used to bypass parliament and even to countermand parliamentary acts, sometimes at the expense of individual rights. The tendency remains in Hungary for its governments to use discretionary administrative instruments as a substitute for parliamentary legislation. Keywords: constitution, decree, patent, rendelet, legislation, Diet, Parliament In 1792, the Transylvanian Diet opened in the assembly rooms of Kolozsvár (today Cluj, Romania) with a trio, sung by the three graces, each of whom embodied one of the three powers identified by Montesquieu as contributing to a balanced constitution.1 The Hungarian constitution, however, was never balanced. The power attached to the executive was always the greatest. Attempts to hem in the executive, however, proved unsuccessful. During the later nineteenth century, the legislature surrendered to ministers a large share of its legislative capacity, with the consequence that ministerial decree or rendelet often took the place of statute law. -

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: the Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918

A Monumental Debate in Budapest: The Hentzi Statue and the Limits of Austro-Hungarian Reconciliation, 1852–1918 MICHAEL LAURENCE MILLER WO OF THE MOST ICONIC PHOTOS of the 1956 Hungarian revolution involve a colossal statue of Stalin, erected in 1951 and toppled on the first day of the anti-Soviet uprising. TOne of these pictures shows Stalin’s decapitated head, abandoned in the street as curious pedestrians amble by. The other shows a tall stone pedestal with nothing on it but a lonely pair of bronze boots. Situated near Heroes’ Square, Hungary’s national pantheon, the Stalin statue had served as a symbol of Hungary’s subjugation to the Soviet Union; and its ceremonious and deliberate destruction provided a poignant symbol for the fall of Stalinism. Thirty-eight years before, at the beginning of an earlier Hungarian revolution, another despised statue was toppled in Budapest, also marking a break from foreign subjugation, albeit to a different power. Unlike the Stalin statue, which stood for only five years, this statue—the so-called Hentzi Monument—had been “a splinter in the eye of the [Hungarian] nation” for sixty-six years. Perceived by many Hungarians as a symbol of “national humiliation” at the hands of the Habsburgs, the Hentzi Monument remained mired in controversy from its unveiling in 1852 until its destruction in 1918. The object of street demonstrations and parliamentary disorder in 1886, 1892, 1898, and 1899, and the object of a failed “assassination” attempt in 1895, the Hentzi Monument was even implicated in the fall of a Hungarian prime minister. -

HSR Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018)

Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018) In this volume: Jason Kovacs reviews the history of the birth of the first Hungarian settlements on the Canadian Prairies. Aliaksandr Piahanau tells the story of the Hungarian democrats’ relations with the Czechoslovak authorities during the interwar years. Agatha Schwartz writes about trauma and memory in the works of Vojvodina authors László Végel and Anna Friedrich. And Gábor Hollósi offers an overview of the doctrine of the Holy Crown of Hungary. Plus book reviews by Agatha Schwartz and Steven Jobbitt A note from the editor: After editing this journal for four-and-a-half decades, advanced age and the diagnosis of a progressive neurological disease prompt me to resign as editor and producer of this journal. The Hungarian Studies Review will continue in one form or another under the leadership of Professors Steven Jobbitt and Árpád von Klimo, the Presidents res- pectively of the Hungarian Studies Association of Canada and the Hungarian Studies Association (of the U.S.A.). Inquiries regarding the journal’s future volumes should be directed to them. The contact addresses are the Departments of History at (for Professor Jobbitt) Lakehead University, 955 Oliver Road, RB 3016, Thunder Bay, ON, Canada, P7B 5E1. [email protected] (and for Prof. von Klimo) the Catholic University of America, 620 Michigan Ave. NE, Washing- ton DC, USA, 20064. [email protected] . Nándor Dreisziger Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2018) Contents Articles: The First Hungarian Settlements in Western Canada: Hun’s Valley, Esterhaz-Kaposvar, Otthon, and Bekevar JASON F. -

Download (2MB)

The Hungarian Historical Review New Series of Acta Historica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae Volume 7 No. 1 2018 Ethnonyms in Europe and Asia: Studies in History and Anthropology Zsuzsanna Zsidai Special Editor of the Thematic Issue Contents WALTER POHL Ethnonyms and Early Medieval Ethnicity: Methodological Reflections 5 ODILE KOMMER, SALVATORE LICCARDO, ANDREA NOWAK Comparative Approaches to Ethnonyms: The Case of the Persians 18 ZSUZSANNA ZSIDAI Some Thoughts on the Translation and Interpretation of Terms Describing Turkic Peoples in Medieval Arabic Sources 57 GYÖRGY SZABADOS Magyar – A Name for Persons, Places, Communities 82 DÁVID SOMFAI KARA The Formation of Modern Turkic ‘Ethnic’ Groups in Central and Inner Asia 98 LÁSZLÓ KOppÁNY CSÁJI Ethnic Levels and Ethnonyms in Shifting Context: Ethnic Terminology in Hunza (Pakistan) 111 FEATURED REVIEW A szovjet tényező: Szovjet tanácsadók Magyarországon [The Soviet factor: Soviet advisors in Hungary]. By Magdolna Baráth. Reviewed by Andrea Pető 136 http://www.hunghist.org tartalomjegyzek.indd 1 5/29/2018 2:40:48 PM Contents BOOK REVIEWS “A Pearl of Powerful Learning:” The University of Cracow in the Fifteenth Century. By Paul W. Knoll. (Education and Society in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, 52.) Reviewed by Borbála Kelényi 142 Writing History in Medieval Poland: Bishop Vincentius of Cracow and the Chronica Polonorum. Edited by Darius von Güttner-Sporzyński. (Cursor Mundi 28.) Reviewed by Dániel Bagi 145 Kaiser Karl IV. 1316–2016. Ausstellungskatalog Erste Bayerisch-Tschechische Landesausstellung. Edited by Jiří Fajt and Markus Hörsch. Reviewed by Balázs Nagy 148 The Art of Memory in Late Medieval Central Europe (Czech Lands, Hungary, Poland). By Lucie Doležalová, Farkas Gábor Kiss, and Rafał Wójcik. -

A Gangesz Partjától a Hunyadiak Hollójáig. Petőfi, Arany És Ady

Irodalomtörténeti Közlemények (ItK) 122(2018) HALMÁGYI MIKLÓS A Gangesz partjától a Hunyadiak hollójáig Petőfi, Arany és Ady történelmi témájú műveinek középkori forráshátteréhez1 Történelmi tárgyú szépirodalmi műveket tanulmányozva fölvetődhet a kérdés: milyen forrásra vezethető vissza az, ami a műalkotásban olvasható? Miként vált a történelmi forrásból szépirodalom? A források ismerete a műalkotás befogadásához is többletél- ményt nyújthat, gazdagabbá teheti az értelmezési lehetőségek körét. Az alábbiakban történelmi témájú magyar szépirodalmi művek forráshátterét vizsgálom, figyelmet for- dítva arra az átalakulásra, ahogy a források ismerete művészetté kristályosodik. „Jöttem a Gangesz partjairól…” India mint őshaza? Ady Endre A Tisza parton című versének jól ismert, nagy erejű kezdősora ez. Bizo- nyára többen fölteszik a kérdést: miért érkezik a vers beszélője éppen a Gangesz folyó partjáról, Indiából? Hogy kerül egy magyar költő Indiába? Adódhat a válasz: sajátos őstörténeti eredettudat állhat Ady verssora mögött.2 A probléma azonban ezzel nem oldódik meg. Fönnáll a kérdés: ismerünk-e olyan eredethagyományt, mely a Gangesz vidékéről származtatta volna a magyarokat? Nem vállalkozom rá, hogy megoldom a kérdést, de szeretném felhívni a figyelmet néhány válaszlehetőségre. A téma tárgyalá- sa lehetőséget ad arra is, hogy a középkori magyar hagyomány indiai vonatkozására is rámutassunk. Ady költészete sokarcú líra. Írt szilaj, háborgó költeményeket, más műveiben azonban a lelki béke iránti vágyat, az Istennel való kibékülés vágyát fejezi ki. Egyes műveiben szembeszáll a keresztény vallással, pogány hitvilág után vágyódik, másutt azonban he- lyet kap költészetében a Krisztus iránti tisztelet. Pogány verseit a fájdalom tüneteként, panaszként érthetjük. Ezek közé sorolható a Lótusz című vers is, mely először 1902-ben látott nyomdafestéket, 1903-ban pedig helyet kapott Méga egyszer című kötetben.3 * A szerző középkortörténész, irodalomtörténész, PhD (2014). -

Anonymus 7.Indd

JUHÁSZ PÉTER ANONYMUS: FIKCIÓ ÉS REALITÁS. AZ ÁLMOS-ÁG HONFOGLALÁSA JUHÁSZ PÉTER ANONYMUS: FIKCIÓ ÉS REALITÁS. AZ ÁLMOS-ÁG HONFOGLALÁSA 2019 A könyv megjelenését támogatta Borítóterv: Majzik Andrea Lektorálta: prof. dr. Veszprémy László ISBN 978-615-5372-96-4 [print] ISBN 978-615-5372-97-1 [online PDF] © Juhász Péter, 2019 © Belvedere Meridionale, 2019 Tartalom Prológus ............................................................................................................. 7 A Gesta kézirata és szerkezete ........................................................................... 9 A Gesta Hungar(or)um – történetírás vagy irodalom? ..................................... 16 Anonymus írói módszerei. A krónikák történelme és Anonymus története .....19 Anonymus és az „ősgeszta” ............................................................................. 21 A Gesta stílusának forrásai A 12. századi francia reneszánsz és a honfoglalók felfedezése ....................... 33 Hivatalnok vagy irodalmár? A hivatalos írásbeliség és a Gesta ...................... 41 Oklevélformulák a Gestában ............................................................................ 44 A Gesta társadalmi ideálja: ellentmondó magyarázatok .................................. 48 A Gesta névanyaga: helyszínek és szereplők ................................................... 53 A Gesta jogi felfogása. Szuverenítás és jogos foglalás ................................... 68 A korhatározás sarokpontjai. A 12. századi Kelet-Európa a Gestában ............73 Gloriosissimus -

Asin Indicate the Presence of the First Wave of the Hungarian Tribes

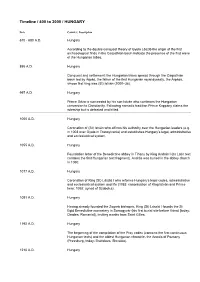

Timeline / 400 to 2000 / HUNGARY Date Country | Description 670 - 680 A.D. Hungary According to the double conquest theory of Gyula László the origin of the first archaeological finds in the Carpathian basin indicate the presence of the first wave of the Hungarian tribes. 895 A.D. Hungary Conquest and settlement: the Hungarian tribes spread through the Carpathian basin led by Árpád, the father of the first Hungarian royal dynasty, the Árpáds, whose first king was (St) István (1000–38). 997 A.D. Hungary Prince Géza is succeeded by his son István who continues the Hungarian conversion to Christianity. Following nomadic tradition Prince Koppány claims the rulership but is defeated and killed. 1000 A.D. Hungary Coronation of (St) István who affirms his authority over the Hungarian leaders (e.g. in 1003 over Gyula in Transylvania) and establishes Hungary’s legal, administrative and ecclesiastical system. 1055 A.D. Hungary Foundation letter of the Benedictine abbey in Tihany by King András I (its Latin text contains the first Hungarian text fragment). András was buried in the abbey church in 1060. 1077 A.D. Hungary Coronation of King (St) László I who reforms Hungary’s legal codes, administrative and ecclesiastical system and life (1083: canonisation of King István and Prince Imre; 1092: synod of Szabolcs). 1091 A.D. Hungary Having already founded the Zagreb bishopric, King (St) László I founds the St Egid Benedictine monastery in Somogyvár (his first burial site before Várad [today: Oradea, Romania]), inviting monks from Saint Gilles. 1192 A.D. Hungary The beginning of the compilation of the Pray codex (contains the first continuous Hungarian texts) and the oldest Hungarian chronicle, the Annals of Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava, Slovakia). -

A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699

A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699 Edited by Gábor Almási, Szymon Brzezi ski, Ildikó Horn, Kees Teszelszky and Áron Zarnóczki Volume 2 Diplomacy, Information Flow and Cultural Exchange Edited by Szymon Brzezi ski and Áron Zarnóczki A Divided Hungary in Europe: Exchanges, Networks and Representations, 1541-1699; Volume 2 Diplomacy, Information Flow and Cultural Exchange, Edited by Szymon Brzezi ski and Áron Zarnóczki This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Szymon Brzezi ski, Áron Zarnóczki and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6687-3, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6687-3 CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Zone of ConflictZone of Exchange: Introductory Remarks on Early Modern Hungary in Diplomatic and Information Networks ....................... 1 Szymon Brzezi ski I. Hungary and Transylvania in the Early Modern Diplomatic and Information Networks Re-Orienting a Renaissance Diplomatic Cause Célèbre: The 1541 Rincón-Fregoso Affair .............................................................. -

General Historical Survey

General Historical Survey 1521-1525 tention to the Knights Hospitallers on Rhodes (which capitulated late During the later years of his reign Sultan Selīm I was engaged militar- in 1522 after a long siege). ily against the Safavid state in Iran and the Mamluk sultanate in Syria and Egypt, so Central Europe felt relatively safe. King Lajos II of Hun- gary was only ten years old when, in 1516, he succeeded to the throne 1526-1530 and was placed under guardianship. In 1506 he had already been be- Between 1523 and 1525 Süleyman and his Grand Vizier and favour- trothed to Maria, the sister of Emperor Ferdinand, by the Pact of Wie- ite, Ibrahim Pasha (d. 942/1536), were chiefly engaged in settling ner Neustadt, where a royal double marriage was arranged between the affairs of Egypt. His second campaign into Hungary, which was the Habsburg and Jagiello dynasties. The government of Hungary was launched in April 1526, led ultimately, after a slow and difficult march, entrusted to a State Council, a group of men who were interested only to a military encounter known as the first Battle of Mohács. It was in enriching themselves. In a word: the crown had been reduced to fought on 20 Zilkade 932/29 August 1526 on the plain of Mohács, west political insignificance; the country was in chaos, the treasury empty, of the Danube in southern Hungary, near the present-day intersection the army virtually non-existent and the system of defence utterly ne- of Hungary, Croatia and Serbia. Both Süleyman and Lajos II partic- glected.